"Roughing it" on the Colville Reservation: The Ernest Moore Foster Collection

By: Kate Semmens '22

Access the digitized Ernest Moore Foster collection via Princeton University Library.

“Let us forsake the hum and bustle, the grime and smoke of the great city, forgetting his worries and cares and tiresome pleasures, and go for a little into some far off place, remote from the busy haunts of men, and there for a while live a new life amid new and stranger surroundings. Let me take the lead now in this personally conducted party and tell you my experience in ‘roughing it’ in the far north west.”

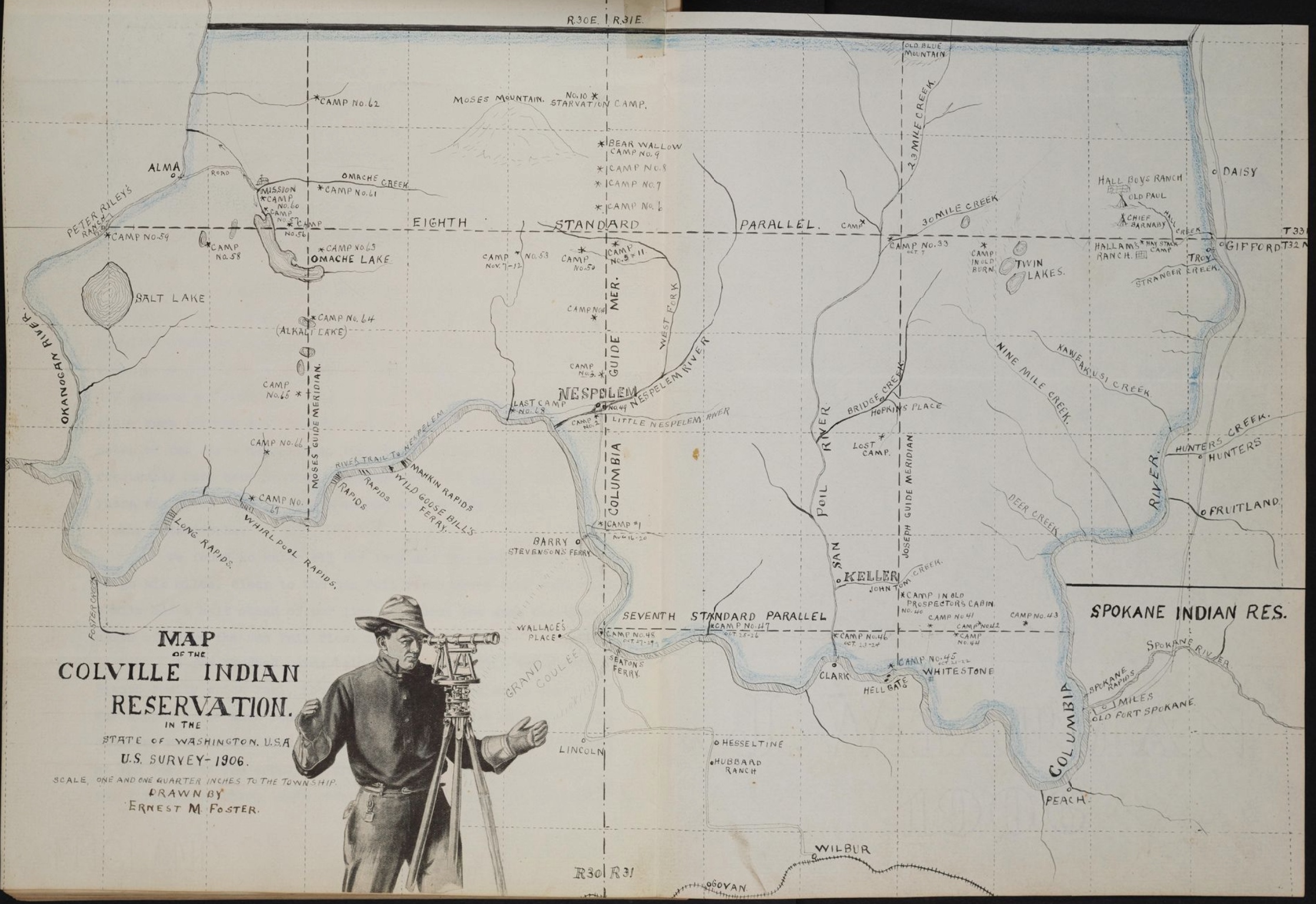

Ernest Moore Foster wrote these words in the opening of his personal account of his time observing the southern section of the Colville Indian Reservation in Northern Washington state. Foster was immersing himself in the remote “Wild West” as part of a surveying trip in August of 1906.

The Ernest Moore Foster collection held in the Princeton Western Americana archives documents this trip in great detail, along with other western trips that Foster took with his father, and later with his wife and children. The collection contains Foster’s letters back home, scrapbooks, photographs, and his typed personal account of the trip, later published as a book entitled With Pack Train and Transit. First Survey of South Half Colville Indian Reservation, 1906, A Personal Account. Foster clearly cared deeply about documenting his travels and experiences, but his interest and observations of the Colville Reservation also reflect broader trends of discourse surrounding Native populations at the time.

Born in 1881, Ernest Moore Foster was twenty-five at the time of the Washington trip. He was a young teacher and bank clerk from Pittsburgh who had a clear fascination with traveling to the American west. [2] Foster wasn’t the typical member of a government surveying project, but this particular survey project was unusual in many ways.

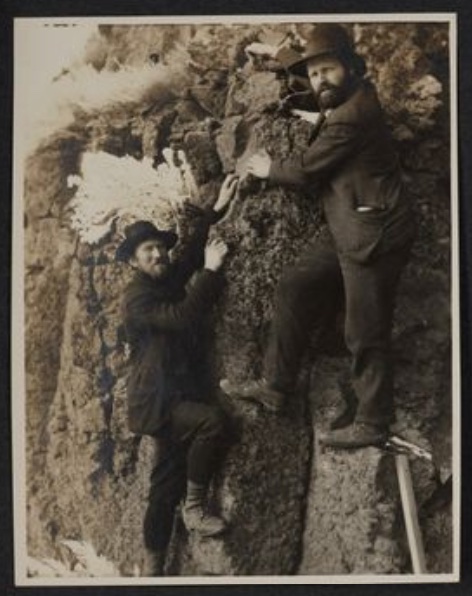

The trip was led by a surveyor by the name of Robert F. Whitham. Robert was born in Pennsylvania in 1852. His father was a Presbyterian minister who had aided in helping slaves escape through the underground railroad. [3] Robert went to the University of Illinois where he studied civil engineering and eventually worked for the Union Pacific Railroad. That job brought him west to Washington. In Olympia, he opened a surveying and architectural firm with his wife’s sister — Mary Louisa Page — who was the first woman in the United States to earn a degree in architecture. After several years working as a surveyor, he received the 1906 contract to survey the southern part of the Colville Reservation. Foster describes Whitham in his journal as “a strongly built man of fifty-odd years, of apparently untiring energy and great endurance. Fifteen years of work in the mountains and forests of the Northwest and Alaska had provided him with the experience necessary to overcome the difficulties that afterwards arose, and he entertained us around the campfire with stories of former surveys, mishaps, and adventures…” [4]

So how did Foster end up on Whitham’s survey project as his main chainman and note keeper? One short biography of Robert Whitham published by the Washington General Land Office claims that Foster was actually Whitham’s nephew. This would certainly be a good explanation for how Foster — who had never surveyed before — ended up on two different contracts with Whitham in Washington. But whether this familial connection is true is hard to prove. Upon looking at ancestry records, the two don’t have any clear connections but do share several family names such as Moore and Page. [5] In addition, Foster talks about Whitham in a very personal way in his writings but never refers to him as family. The two seem to have been quite close. Foster describes their relationship as “intimate” and refers to their prior trips together to Mount Helens and their nighttime observations of the North Star. [6]

What makes this question of a family relationship even more complicated is that, according to the General Land Office documents, Whitham’s contract for the Colville Reservation was a joint contract with his son. [7] Paul Page Whitham was also a surveyor and was most likely on the contract jointly so that the contract could be larger and cover more land. However, it doesn’t seem that he was involved in the survey directly. He isn’t mentioned in Foster’s account of the trip. There was another man on the trip by the name of Paul, however. He is mentioned in several of the photograph captions in Foster’s scrapbook. In his letters, Foster says that he was as an addition later in the trip after another man quit. This Paul was Paul Moore, who Foster seemed to also grow quite close to. In some letters Foster’s writing even makes it sound like Paul is familiar to his own family. They traveled around the west together after the surveying trip was completed. [8]

Also on the trip were several other odd characters. There was W.A. Adams, who Foster referred to as “Bill.” He was a “stockily built young Pennsylvanian” who was “the life and wit of the party…” [9] Foster shares that some of the group’s cooked meals along the trip got burnt because Adams’ jokes were so distracting. There was also John Thompson of Olympia, Washington, who was Norwegian by birth and is described as quite “good looking.” [10] And there was the cook Raymond W. Hatton who was always humming songs along the trails and would become a famous Hollywood movie star some years later. It was quite the assortment of men coming together in Seattle and embarking on a four-month trip together into unexplored “Indian territory.”

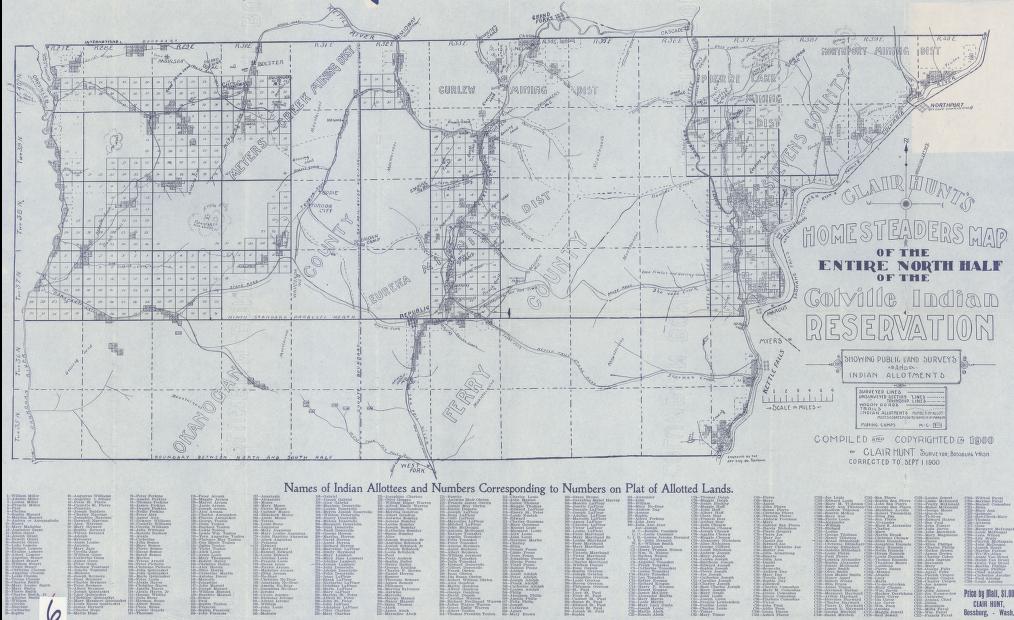

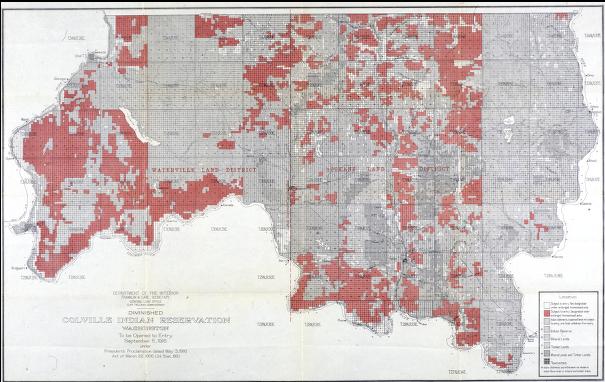

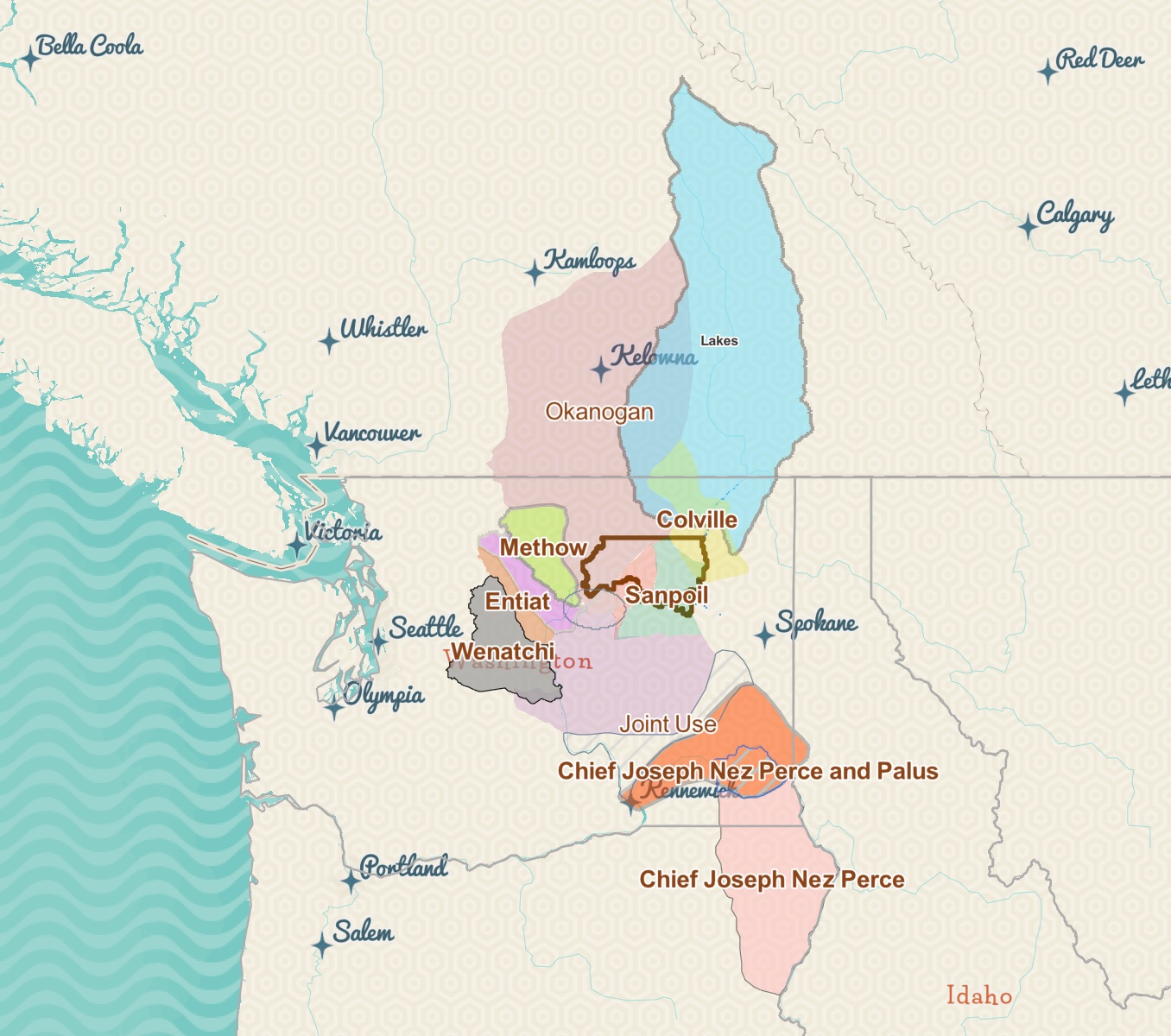

The Colville Indian Reservation is in the Northeastern part of Washington State not too far from the city of Spokane. The original reservation was established by Presidential executive order on April 9, 1872. [11] The reservation then shifted several times and shrunk dramatically in size in the months and years after its establishment. Then came the General Allotment Act of 1887 — also known as the Dawes Act. The Dawes Act centered around the idea that introducing private property to Native tribes could “civilize” them and in the process could open up more land for European-Americans. From 1887 to 1934, Native-owned land holdings went from 138 million acres to just 50 million. [12] It was unsurprising then that the Colville Reservation would be included in these new allotment policies. In 1892, Congress passed an act that withdrew the reservation status from the Northern half of the Colville land. The Northern land once again became public domain and was opened to settlement by non-Indians. Then, in 1906, another act was passed that allowed for the opening of “surplus lands” in the South half of the reservation to settlers. [13]

This act seems to have prompted the survey of the Colville Reservation in August 1906. The survey was conducted through the General Land Office in Washington, which is associated with the broader U.S. Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Land Management. This wasn’t a traditional mineral survey but was instead entirely focused on figuring out how best to divide up land for potential homesteaders. It seems that the General Land Office was anticipating the need for surveying of the large reservation. Very few articles write of or announce the survey, but one article refers to the survey as the "Meridian Survey" and tells readers that the survey is set to finish by December. What is particularly interesting, however is what the short article writes of Mr. Whitham's job. It reads, "Mr. Whitham says he is doing the blocking out of the work, and by him completing his contract on the first of December the seven other contracts who are to finish the survey will be able to begin work early in the spring." [14] So it is clear that this particular team was just one of many teams that were working all together under Whitham's and the General Land Office's supervision.

The 1906 survey that Foster took part in covered 114 miles along the Moses Guide meridians, along with another 106 miles on parallels along the Columbia River. [15] The surveyors were often quite near Nespelem, which is one of the largest cities on the reservation and at the time was where the Nez Perce tribe was located. They often left or bought items in Nespelem and received and sent their mail at the Nespelem post office.

The survey was organized by the government of Washington and not the federal government and was in anticipation of something that would only come many years later in a different form. In 1916, Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation that opened lands in the “diminished” reservation. [16] That executive action was what this survey work was anticipating. Following Wilson's proclamation, a map was drawn laying out which areas of land would be opened. It is quite likely that it is this survey team's work that shaped that map and the allotments it presented.

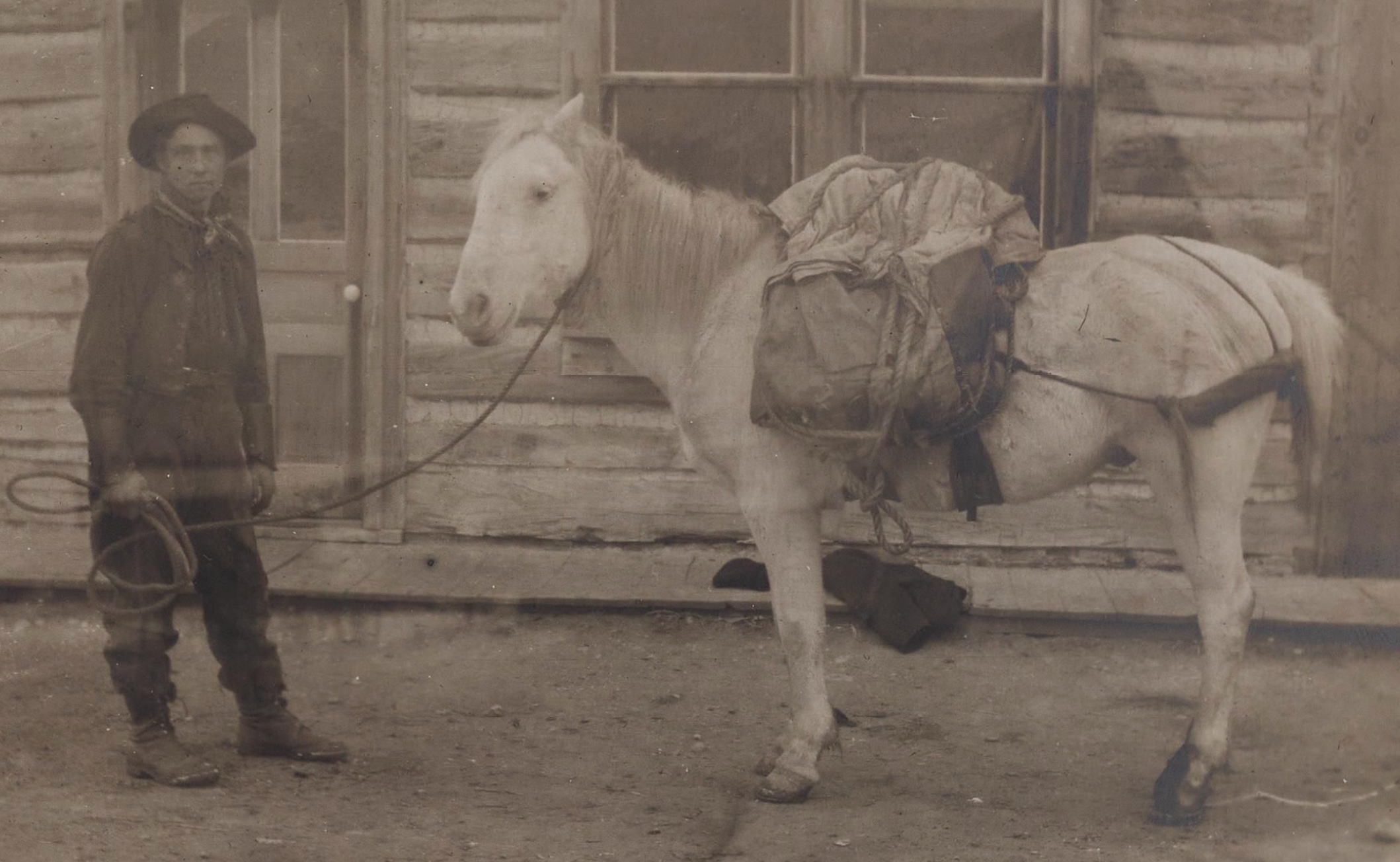

Based on Foster’s writings, the actual survey seems to have consisted of walking in straight lines up and down, dragging a chain along to make the division lines, and taking notes on the terrain and the various opportunities for farming. In a letter to his father “Pa” back in Pittsburgh, Foster describes the surveying process. He writes, “We usually run the line about three miles a day, sometimes three and a half, but yesterday we could only make two. We go in a perfectly straight-line up hill and down dale and have never varied more than about four feet. The country is much more rugged than we anticipated so we decided to leave the tents and all unnecessary articles at Nespelem until we should have more need for them.” [17] The land was woody with large pine trees but it also was great land for horses. That was what Foster told his brother Will was the best future for the land so that men didn’t have to rely on machinery coming in on the railroad. [18]

Foster seemed to enjoy surveying and told his father that “it agrees with me finely.” But he also told his father in a letter that he didn’t want to continue with this “kind of work,” because “there is not enough money in it.” [19] He makes clear to his father that money wasn’t the reason he took the opportunity in the first place but that he won’t be continuing with survey work in the long term. It seems instead that for Foster the opportunity was about new experiences and seeing new places. Foster wrote to his brother:

“I am certainly ‘seeing the West’ now, and pretty much as in the days of ‘49, for this country is uninhabited save by the Indians who live in the southern part, and it has never even been surveyed before. Some of the land is fine and some is absolutely worthless and will probably always be a wilderness. We do not know yet what system will be used when the reservation is opened, or the conditions, but we are making notes of desirable sections. Several of our men are old timers and know land when they see it.”

The survey trip’s goal was about recognizing good land and taking note of it, but for Foster it was also an adventure to another world and time. The “West,” as he saw it, was transporting him back to the days when the West was the new frontier that hadn’t been explored. To these White men, that was very much what the Colville Reservation was as well. It was an un-surveyed and unexplored land of potential that to them wasn’t being utilized properly by the Native tribes.

But no matter what this group of men thought of the land, the tribes of the Colville Reservation were very much active and present when the survey was taking place. The Colville Confederated Tribes include the Moses-Columbia, San Poil, Nespelem, Methow, Entiat, Colville, Lakes, Wenatchee (Wenatchi), Chief Joseph’s Nez Perce, Palus, Southern Okanogan, and Chelan. [20] It seems that the survey team interacted the most with the Nez Perce, Colville, and Nespelem based on location, photographs, and Foster’s journal and letters. He tells many stories of brief interactions with Indians on the reservation.

In a letter to his brother Will on September 30th, 1906, Foster describes making a six-mile trip to visit the home of Chief Barnaby — the well-known Chief of the Colville who was directly involved in land negotiations and agreements such as the McLaughlin Agreement of 1905. [21] The McLaughlin Agreement was the application of the Dawes Act to the South Half section of the Colville Reservation. [22] An Indian government agent met with representatives of the Colville tribes and reached a form of agreement with them that included the traditional promise of 80-acre allotments. It is important to note, however, that these types of meetings and “agreements” were really only to decide upon details. They weren’t an opportunity for tribes to oppose the allotment of their land.

Foster describes visiting Chief Barnaby’s tepee and being interested in purchasing a pair of moccasins from him. Foster writes, “He was not at home, but we looked into his tepee.” [23] Blunt and invasive actions like this were not uncommon for Foster and his fellow surveyors. In a letter sent later in November of 1906, Foster described a time when the survey team was looking for a place to camp and supplies and came upon two houses. There was nobody home and so they broke through the windows of one of the homes with an axe. Foster wrote to his sister Elsie, “The cabins were evidently those a squaw man and there were Indian curios galore. We would all have been glad to have purchased some but had to leave them behind.” [24]

Foster seems to have been very personally fascinated with Indian objects and culture. Through his letters and journals, it becomes clear that much of his detailed documenting was done not only because he saw the trip as a new and adventurous experience of ‘roughing it’ in the wild west, but also because he enjoyed collecting and documenting what he saw as unique and different. One of the ways he documented his travels and encounters with Indian cultures was through photography. Foster mentions several times in his letters owning cameras and his plans for his camera that was being sent to him at Nespelem. In one letter to his father, Foster describes several instances when he wished he had his camera already. “We saw a sight yesterday which would have made a good picture — a buck traveling with his family. The squaw had one papoose tied to a board and another one sling in a blanket behind her on the saddle. Then there was a little boy of about six and an old squaw. They were Nez Perce and were all on horseback bound for Idaho.” [25]

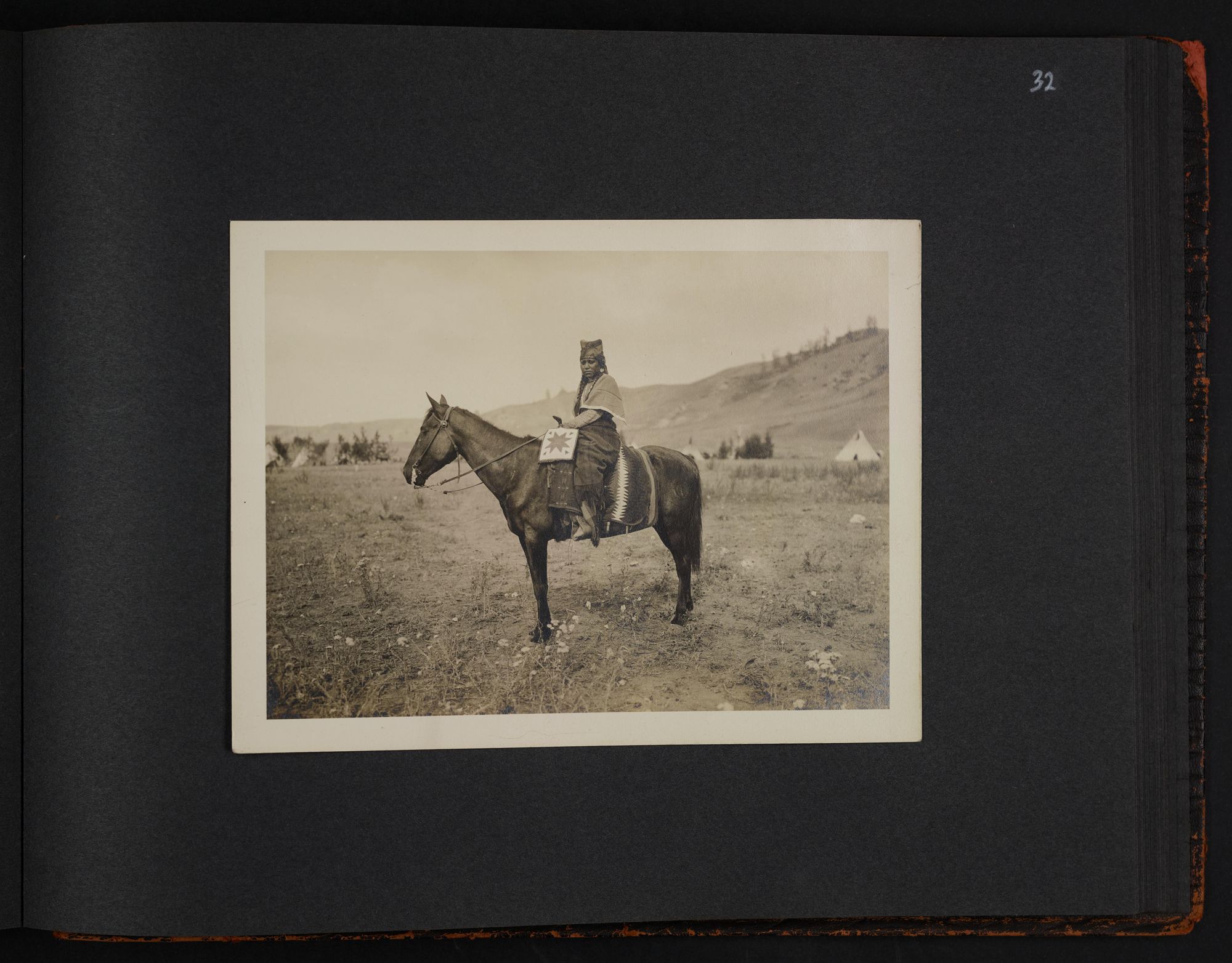

This image that Foster describes is quite similar to one that is included in his “Western and Indian Photo Album.” [26] Foster didn’t have his camera to take the photo he described but one of his photos in his album is of a Nez Perce woman on horseback with a baby in a papoose and board. Foster’s collection of photos of Colville Indians is a significant part of what makes Ernest Moore Foster’s collection unique. There are nineteen photographs of what is assumed to be Colville Reservation Native Americans. In my research to discover more about these photographs and their subjects, I confirmed that none of these photographs were taken by Foster himself.

The photographs were taken by Edward H. Latham, who was the agency physician on the Colville Reservation for many years. Many of the same prints and the original negatives of the photographs in Foster’s collection can be found in several different archives including University of Washington’s special collections, Whitman College’s Northwest Archives, and on Plateau People’s Web Portal, which cites its photographs back to Washington State University’s special collection on the Colville Reservation. [27] Latham first became physician on the reservation in 1890 and most of his photographs seem to have been taken in the early 20th century. Additionally, these collections identify Latham’s photographs as being of mainly Nez Perce Indians. Many of his photographs — including several of the prints in Foster’s collection — are identified as being taken in 1904 at the famous Nez Perce Chief Joseph’s funeral. [28]

Latham was an amateur photographer who had an interesting life in Washington as a doctor. He was not in any way a famous photographer. It is because of this that many of his photographs have actually been previously miscredited by dealers and collectors to the well-known photographer Edward Curtis. [29] The photographs in Foster’s collection have no captions but are identical prints of other photographs that are accessible through the University of Washington, which holds the original negatives.The fact that these photographs are not Foster’s fits in with his letters and journals that describe him not receiving his camera until much later in the trip. In addition, the photographs are posed and professional in setting. Most of the photographs are of Nez Perce in traditional dress that was reserved for special occasions and they are in posed stances on fur rugs with makeshift portrait backdrops. These are photographs that display a certain level of trust between the subjects and photographers — a trust that is not displayed in the encounters between the survey team and the reservation populations.

In Foster’s first letter to his older sister Elsie in September of 1906, Foster describes one Indian woman’s reaction to the surveyors and the chain that they used to measure and draw lines of potential allotments. He writes:

“Yesterday morning we crossed a field belonging to a very old Indian squaw and we had both our chains fastened together so that they stretched out a thousand feet. She found the chain and came to us very much agitated, evidently thinking that we were going to take some of her land, although we could not understand a word she said. She will probably lose some of it when the Indians are allotted as their farms will be squared up to conform with section lines and each will get eighty acres. This considered to be the best part of the Reservation and the land is certainly good."

There is an acknowledgement by Foster of the Indian woman’s worries and their inability to communicate. Yet at the same time Foster also quickly accepts that her fears coming true will and should happen. “The land is certainly good” and so it will be divided and forcefully given from this woman to white homesteaders.

Foster’s selected Latham photographs were most likely purchased at some point during his trip. At one point in his letters he mentions having paid for photographs, but it is impossible ot know if that was these. I would guess that Latham was still around on the reservation and that his photographs would’ve been for sale or for taking in Nespelem. What is interesting, however, is that most of the photographs that Foster has are of the Nez Perce in their most traditional clothing. If one looks at Latham’s more extensive collection held by the University of Washington, a lot of his photographs are not as posed and capture the Nez Perce in a more casual dress and setting.

Foster’s selection of Latham photographs that he chose to preserve and highlight in an album of his trip speaks to the way he viewed the Nez Perce and the Indians of the Colville Reservation more broadly. He saw them as fitting into his own preconceptions of Native populations and their traditional dress and babies in papooses all fit with his understanding of Indians as the “other” that was less civilized and experienced with utilizing land. Though not a professional surveyor or engineer, Foster became an active player in the aftermath of the 1887 Dawes Act by participating in this survey. The Dawes Act set out to assimilate Native populations and force them to adhere to European American understandings of farming, land, and government. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the United States saw Native populations as an “other” that needed fixing and Foster and the rest of the surveying team very much saw the Colville Tribes in the same light. [31] Yet, while holding this view of them as the “other,” Foster found the tribes’ culture endlessly fascinating. He worked to document his observations and experiences and collected photographs, items, and arrowheads. The Ernest Moore Foster collection in many ways documents the exact unique culture that the survey and broader allotment and reservation laws were erasing.

[1] “With Pack Train and Transit.” U. S. Geological Survey: Southern Half of Colville Indian Reservation, Washington State, p. 1; Ernest Moore Foster Collection, WC042, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

[2] Jerry Olson, “Short Biographies and Personal Notes S-Z of All of the Surveyors and Individuals Associated with the General Land Office in Washington, 1851-1910,” Surveying North of the River, Second Edition, p. 506, February 3rd, 2020, https://www.olsonengr.com/sites/default/files/surveying-history/files/glosurveyorspublishsz.pdf AND “Guide to the Papers of Ernest Moore Foster 1739-1984 | Historic Pittsburgh,” accessed April 5, 2022, https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt%253AUS-QQS-MSS217/viewer.

[3] Jerry Olson, “Short Biographies and Personal Notes S-Z of All of the Surveyors and Individuals Associated with the General Land Office in Washington, 1851-1910,” Surveying North of the River, Second Edition, pgs. 505-506, February 3rd, 2020, https://www.olsonengr.com/sites/default/files/surveying-history/files/glosurveyorspublishsz.pdf.

[4] “With Pack Train and Transit.” U. S. Geological Survey: Southern Half of Colville Indian Reservation, Washington State, p. 2.

[5] “Public Member Trees,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 21 April 2022), “Marcy III Family Tree” https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/family-tree/tree/22472604/family/familyview?cfpid=18019832048&fpid=1244653277 AND “My Family File Copy 2” https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/family-tree/person/tree/1215957/person/6156984755/story?ssrc=.

[6] Letter to “Will,” September 2, 1906, p. 3. Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection, WC042, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

[7] Jerry Olson, “Short Biographies and Personal Notes…,” Olson Engineering, March 18, 2020, 507. https://www.olsonengr.com/sites/default/files/surveying-history/files/glosurveyorspublishae.pdf

[8] Letter to “Mother,” December 7th, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster’s Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[9] “With Pack Train and Transit.” U. S. Geological Survey: Southern Half of Colville Indian Reservation, Washington State, p. 2.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Reservation Lands - North Half Allotments,” Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, The History and Archaeology Program, Trisha Johnson. June 16, 2021. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bb31cd48d0284fa59d6f454cafabe962

[12] “General Allotment Act of 1887 (Dawes Act).” Native Americas XIV, no. 1 (Mar 31, 1997): 20. https://login.ezproxy.princeton.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.princeton.edu/scholarly-journals/general-allotment-act-1887-dawes/docview/224759672/se-2?accountid=13314.

[13]“South Half Bill Passes: Colville Reservation Project Up to President,” The Spokesman-Review, March 9, 1906, AND “Reservation Lands - North Half Allotments,” Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, The History and Archaeology Program, Trisha Johnson. June 16, 2021. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bb31cd48d0284fa59d6f454cafabe962.

[14] “At Work on Meridian Survey,” The Spokesman-Review, October 17, 1906, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[15] Meridians are imaginary lines of longitude north to south and ranges are the lines from east to west. Combined they defined sections of states and townships. These were referred to as guide meridians and were published by the GPO and the Bureau for Land Management. Public surveys followed and used these guides to survey and divide up work. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ListofprincipalandguidemeridiansandbaselinesoftheUnitedStates#cite_note-gposm-1. The Moses Guide Meridian is not discussed widely or published in common lists but might have been an old name for the Colville Guide Meridian.

[15] Jerry Olson, “Short Biographies and Personal Notes…,” Olson Engineering, March 18, 2020, 507. https://www.olsonengr.com/sites/default/files/surveying-history/files/glosurveyorspublishae.pdf AND “A Brief History of the General Land Office in Washington,” Surveying North of the River, Olson Engineering. https://www.olsonengr.com/sites/default/files/surveying-history/files/briefhistory.pdf

[16] “Reservation Lands - South Half Allotments,” Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, The History and Archaeology Program, Trisha Johnson. June 16, 2021. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bb31cd48d0284fa59d6f454cafabe962.

[17] Letter to “Pa,” August 26, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster’s Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[18] Letter to “Will,” September 2, 1906, p. 3. Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[19] Letter to “Pa,” August 26, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster’s Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[20] “Colville Tribes,” Colville Tribes, 2022, https://www.colvilletribes.com.

[21] Letter to “Will,” September 30th, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[22] Frank Fuller Avery, “Signers of the McLaughlin Agreement” (Photograph, Colville Reservation, Washington, December 1, 1905), Frank Fuller Avery Collection (PC 19), Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal, Washington State University Libraries., https://plateauportal.libraries.wsu.edu/digital-heritage/signers-mclaughlin-agreement AND See S. Exec. Doc. No. 15, “Message from the President of the United States, Transmitting a Communication from the Secretary of the Interior, Submitting an Agreement with the Indians of the Colville Reservation for the Cession of a Part of Their Lands” (United States Senate 52nd Congress, 1st Session, January 6, 1892), Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, University of Oklahoma College of Law.

[23] Letter to “Will,” September 30th, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[24] Letter to “Elsie,” November 18th, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[25] Letter to “Pa,” October 28th, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[26] Western and Indian Photo Album, p. 32; Ernest Moore Foster Collection, WC042, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

[27] See Edward Latham Collection, American Indians of the Pacific Northwest Images, University of Washington Libraries. https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/loc/search/searchterm/latham%2C%20edward%20h./field/photog/mode/exact/conn/and AND Plateau Portal, https://plateauportal.libraries.wsu.edu/digital-heritage?searchapiviews_fulltext=Latham AND Claire Drown, “Edward H. Latham Photographs,” Archives West Orbis Cascade Alliance, 2018, https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv845549.

[28] Edward H. Latham, “Peo Peo Tholekt at Chief Joseph’s Funeral,” 1904, Washington State University Manuscripts Archives and Special Collections, Nez Perce, Accessed via Plateau Portal. https://plateauportal.libraries.wsu.edu/digital-heritage/peo-peo-tholekt-chief-josephs-funeral.

[29] Claire Drown, “Edward H. Latham Photographs,” Archives West Orbis Cascade Alliance, 2018, https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv845549.

[30] Letter to “Elsie,” September 23rd, 1906, Letters to Ernest M. Foster's Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

[31] Foster writes in a letter to his father: “The Nez Perce are more intelligent than the Siwash, and paint their faces red, but I don’t think that is because of their superior intelligence. Most of the Indians have cabins but live in tepees outside. They have lots of horses but no cattle. We have only seen one farm of any considerable size, that is what they call the ‘big ranch’ and embraces about a section or two." Here we can see his thoughts of Indian culture as less civilized and "other." Letter to “Pa,” August 26, 1906, p. 2-3, Letters to Ernest M. Foster’s Family; Ernest Moore Foster Collection.

![Map of Northern Half of Colville Reservation. Map from Spokesman-Review, September 3rd 1900. [FOOTNOTE]](/uploads/spotlight/attachment/file/1571/Map_of_Colville_Reservation_-_North_Allotment.jpg)