“I’d Rather Be Ordinary”: Uncovering the True Motivations of One "Broomstick" Scientist after World War II

By Claire Schmeller '23

Where should one's mind be when conducting classified military research? The life of a White Sands Broomstick scientist as illustrated through his personal letters reveals the challenges and emotions that arose from balancing life as an enlisted engineer and a newlywed.

“Do I resemble a witch cruising aloft on a jet-propelled broomstick?” asked Warren Alfred Stark in a letter to his fiancé on March 30, 1951.[1] One of a select number of men who worked as “broomstick scientists” at the White Sands Proving Grounds (WSPG), he made use of his specialized Mechanical Engineering degree in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

The term "broomstick" comes from the ability of the V-2 rocket to guide itself through the air. These scientists were “enlisted men with technical education in science and engineering who were drafted and assigned to White Sands to assist on several missile projects.”[2] White Sands is just outside the city limits of Las Cruces, but in his time stationed there, Stark was not a frequent visitor of the city.

The United States military ordered these high level operations to match or out-perform this technology at the precipice of the Cold War era. Between 1950 and 1952, Stark showed, in letters to his fiancé, that he simultaneously balanced this work and his own attempt at the American dream. Unlike the rockets he was working on, his drafted enlistment in 1950 prevented him from having the freedom to act as his own self-guiding force.

“Do I resemble a witch cruising aloft on a jet-propelled broomstick?”

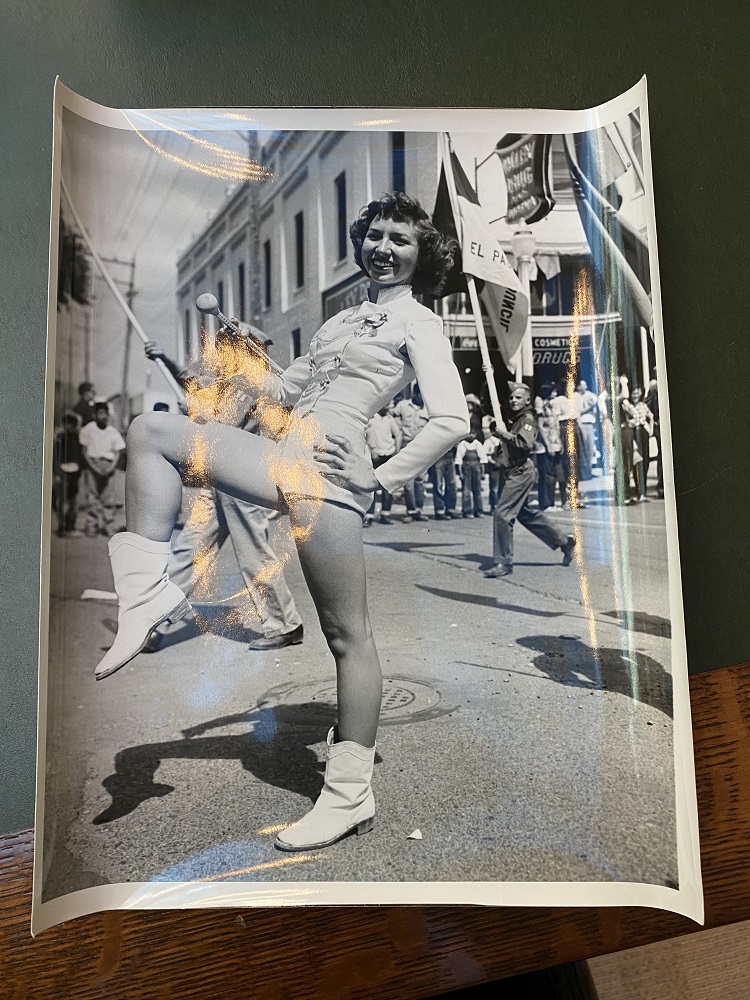

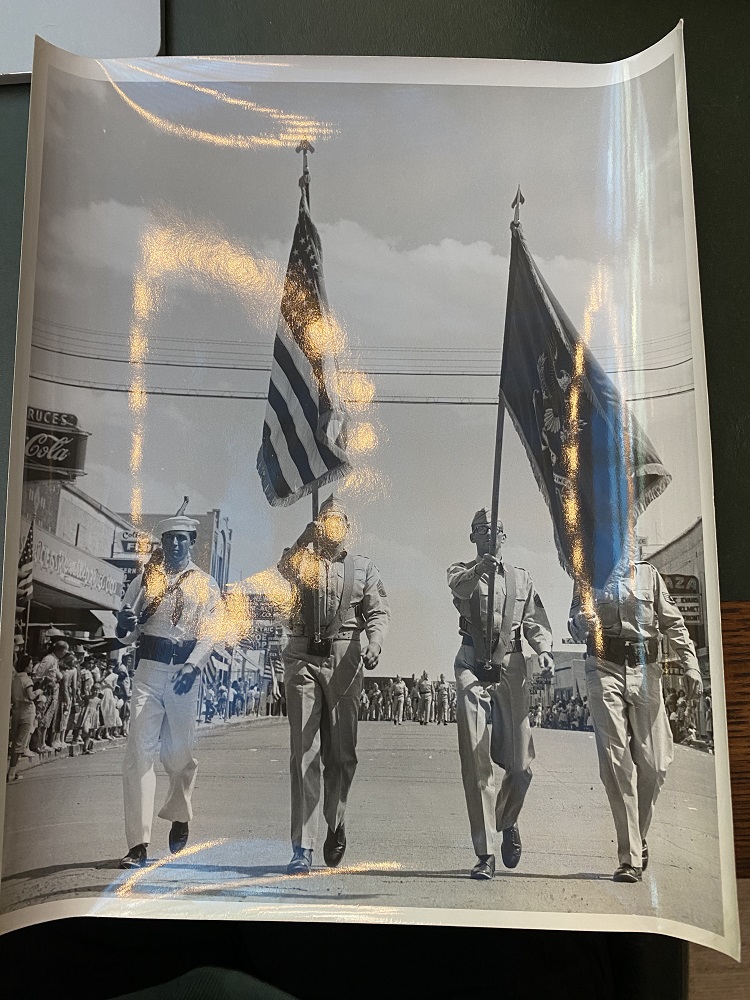

The Warren A. Stark Papers include a large collection of letters and ephemera that Warren Stark sent or received. Most remain in their original envelopes. The letters begin in December 1950 and continue until September 1952. There is an accompanying box of photographs, which primarily depict one 1952 parade in the town of Las Cruces. The photos measure 7 in by 10 in and each have a U.S. Army Ordnance Corps stamp on the back. There are close ups of majorettes as well as larger group shots of the soldiers marching in the parade without further identification.

Presumably the heirs of Warren Stark collected these saved letters for archival purposes. Stark himself wrote that he was “gonna [sic] bring [Jeannie’s] letters back home with me, for safe keeping since I have quite a number of them since Ft. Myer, VA.” [Warren to Jean, May 8, 1951] Stark clearly kept the letters as mementos of his relationship with his fiancé and later wife. As Stark wrote in the same note to Jean, “I’ll trade you letter for letter and read mine to you in person.” The collection now holds interest because of his proximity to military operations.

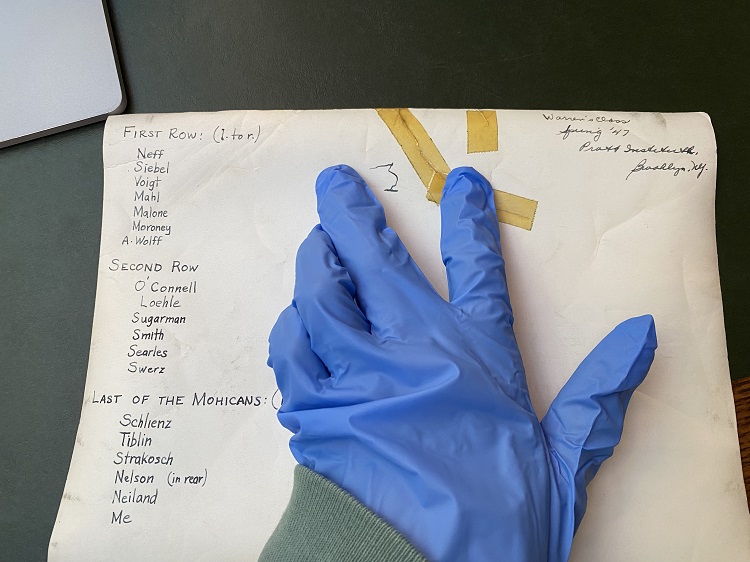

Stark was born on August 28, 1928, growing up in Brooklyn, NY. There, he attended Brooklyn Technical High School and the Pratt Institute, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1949.[3] As an engineering student, he was part of the executive leadership of the now inactive local chapter of Tau Beta Pi, the “engineering honor society.[4] He registered for the draft when he turned 18 in 1946.[5]

The letters place the beginning of his service at Fort Dix, New Jersey with a brief placement in Ft. Myer, VA (apparently for all or most of the month of February), although he spent most of his time at White Sands. Stark’s fiancé and later wife, Jean Baldwin Stark, was the main recipient of Stark’s saved letters and the author represented second-most in the collection. The letters specifically show what life is like when the two individuals are on their own and therefore apart. Their contents run the gamut from gushing effusions of love and logistical questions about sending a pen restock, to an occasionally detailed look into the everyday aspects of life at the White Sands Proving Grounds. Since there is no written record of their time together, the long-distance nature of his military assignments seem to have been the foundation for this collection in the first place.

Stark was madly in love. One cannot omit the label of love letter in the classification of these materials. Indeed, his first thoughts upon arrival to White Sands were, "I'd rather be ordinary so I could [stay] at Fort Dix." [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951] Constantly pining for closeness to his lover, his own writing focuses so heavily on his love for his wife that one would struggle to represent the letters contents in any other way. This highly specific lens does not offer much room for misunderstanding or exaggeration.

"I'd rather be ordinary so I could [stay] at Fort Dix."

Stark started at Fort Dix in December, 1950. Occasionally, he wrote summaries of his letters on the outside of the envelopes; in his first month, he wrote “artillery practice, M1-rocket launcher,” as well as “gas mask practice!” [Warren to Jean, 12/18/50 & 12/5/50] This type of basic training would not define Stark’s larger experience. Stark differentiated his role as an engineer, explaining, “they are taking men both here at WSPG + elsewhere for rotation to Korea!) I think they’re sending only those men who have been in the Army for a number of years, though. So don’t worry about me. I’ll be given a MOS (Military Occupation Specialty number) which will be exempt from going overseas, when I get assigned after this electronics course.” [Warren to Jean, May 12, 1951] While others were going abroad to serve on the frontlines of the Korean War, Stark's engineering skills confirmed that he would not. It is not articulated directly, but one can only imagine the relief that this brought to his partner and family.

Stark entered his service with the rank of Private First Class in 1950, and upon his exit in 1952, he had achieved the rank of Corporal.

Throughout, his heart was with his fiance Jean Anne Baldwin. Born on July 27th, 1928, in Canarsie, Brooklyn, she and Stark announced their engagement before his enlistment.[6] She worked as a teacher at Amityville Junior High School in the three years of letters, also living in the town of Amityville, NY, on Long Island. She is represented as an expectant homemaker and perhaps more reluctant worker on the home front. Ms. Baldwin (affectionately referred to as Jeannie) lived at 46 Ireland Place, which is labeled as the home of Mr. and Mrs. Wich on the back of the photo of the house, starting on August 21, 1950. The arrangement between Baldwin and the Wich's is not immediately clear but it is at least confirmed that she received and sent letters from that address until she and Stark bought their own house.

“I don’t care for this part of the U.S. at all. Just vast stretches of land and it takes so long to get anywhere, even at 60 and 70 mph.” [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951]

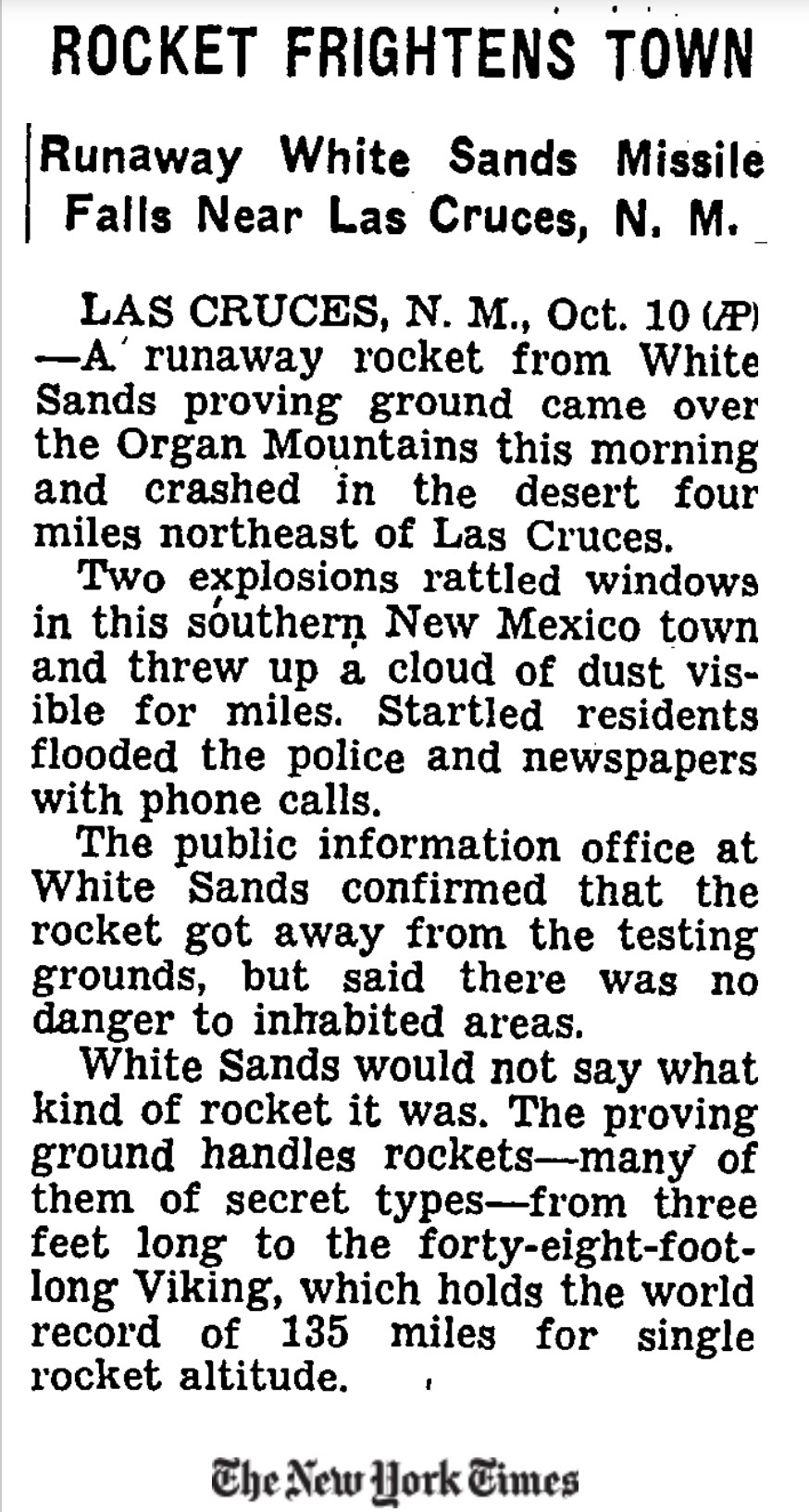

On October 11, 1951, the New York Times published a notice of a stray missile in the town of Las Cruces. In the words of the White Sands public information office, the "rocket got away from the testing grounds but... there was no danger to inhabited areas." The article reported this just after clarifying that "startled residents flooded the police and newspapers with calls."

These were the projects Stark was working on, yet he was not engaged with the surrounding civilians; it is nonetheless helpful to explain a bit more about the location-based debate contemporary to this time period.

President Herbert Hoover approved the creation of White Sands as a National Monument in 1906. Initially subject to various failed mining operations, locals quickly realized that its iconic dune fields would be a better fit for the requirements of federally protected land, which were “economic worthlessness and monumentalism.”[7] Some were more appreciative of its charm than others. Stark wrote to his fiancé upon his arrival to the Proving Grounds, “I don’t care for this part of the U.S. at all. Just vast stretches of land and it takes so long to get anywhere, even at 60 and 70 mph.” [Stark, March 8, 1951] The open spaces and desert landscape did not satisfy Stark. That attitude differed from the larger trend of the time, where “pent-up demand during the war resulted in the "baby boom," …that brought highly mobile and large families in their automobiles to White Sands and other scenic attractions in the West.”[8] Indeed, over 4,000 visitors showed up for the opening of the National Monument, and almost 34,000 people came through the park in its first year.[9]

At the same time, White Sands became a source of conflict between the value of land preservation and military development. Contemporary statistics represent that the park protects 41% of the dune fields, while 59% of the same area is located on the land of the missile range.[10] During World War II, stray shells from the missile tests dropped onto the White Sands National Monument constantly. Cartographical discussions in 1947 produced a map of the Proving Grounds which suggested that it would completely surround the Monument. That said, "military imperatives prevailed over local concerns when on April 1, 1949, the Army and park service drafted a new permit for joint use of White Sands. The MOU [Memorandum of Understanding] declared that "physical use of the monument is not desired by the Armed Services," and that 24 hours' notice of evacuation would be given prior to test firings.”[11] This failed to address the disruption to the local community, and although the park remained, the presence of the military operations defined the land more and more.

Soon enough, however, Stark settled into his role. He wrote to Baldwin that he finally “felt a little bit at home tonight.” [March 8, 1951]

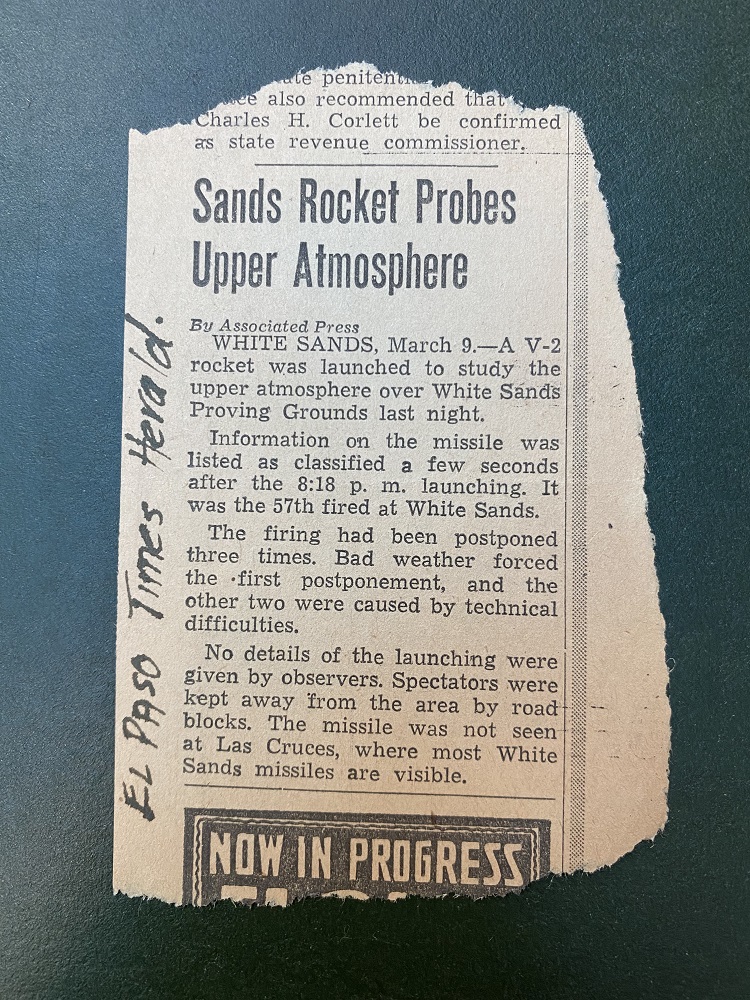

A newspaper clipping indicated the interest of the surrounding area in the goings on of the missile range. [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951] While still disruptive, the secretive nature of the research provided some intrigue.

Stark included a lot of local newspaper clippings in his letters. They contain his light annotations, which usually relate to personal matters or his thoughts and reflections. That said, all the articles in the clippings and pages hold value as a local, and largely unarchived, record of the time period.

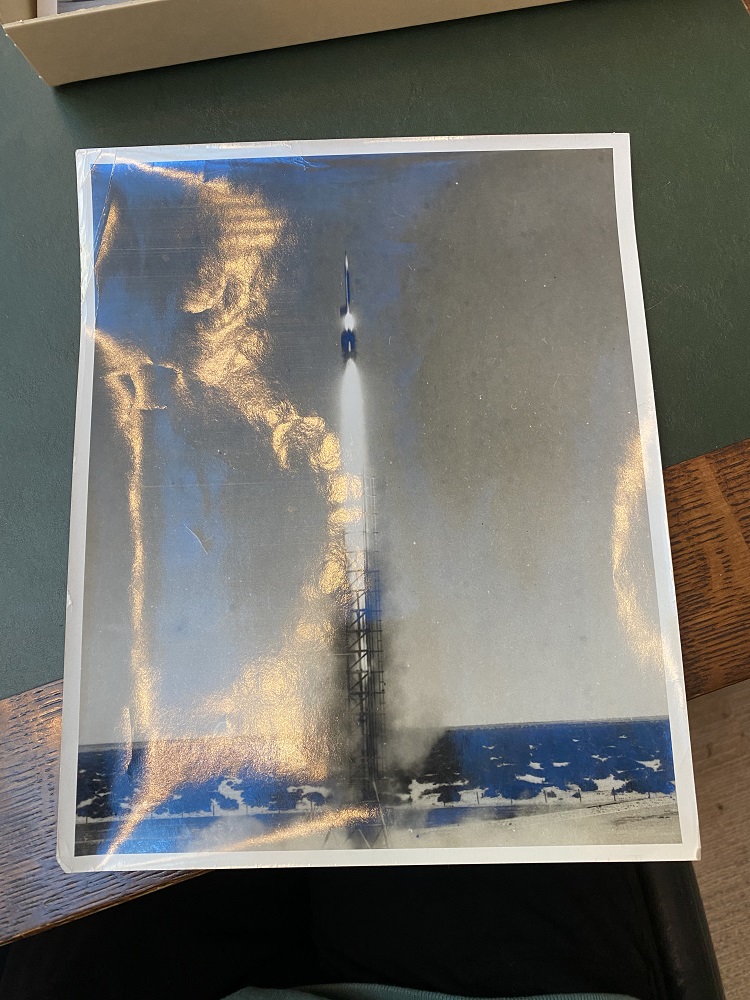

The missile launches undeniably disrupted the area. Stark described the March 8th launch to Baldwin as the missile having “took off slowly in a bright ring of flame and kept going up slowly, giving off sparks all the time. Then, about 800 yards or a mile perhaps, up in the air, it toppled over + started down. When it hit, it exploded in a tremendous ball of flame + it took 15 seconds or more for the sound to reach camp (7 miles away). Some shock + shaking of buildings even at this distance. It landed almost too close to the weather station in the desert where 100 or so people were watching.” [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951]

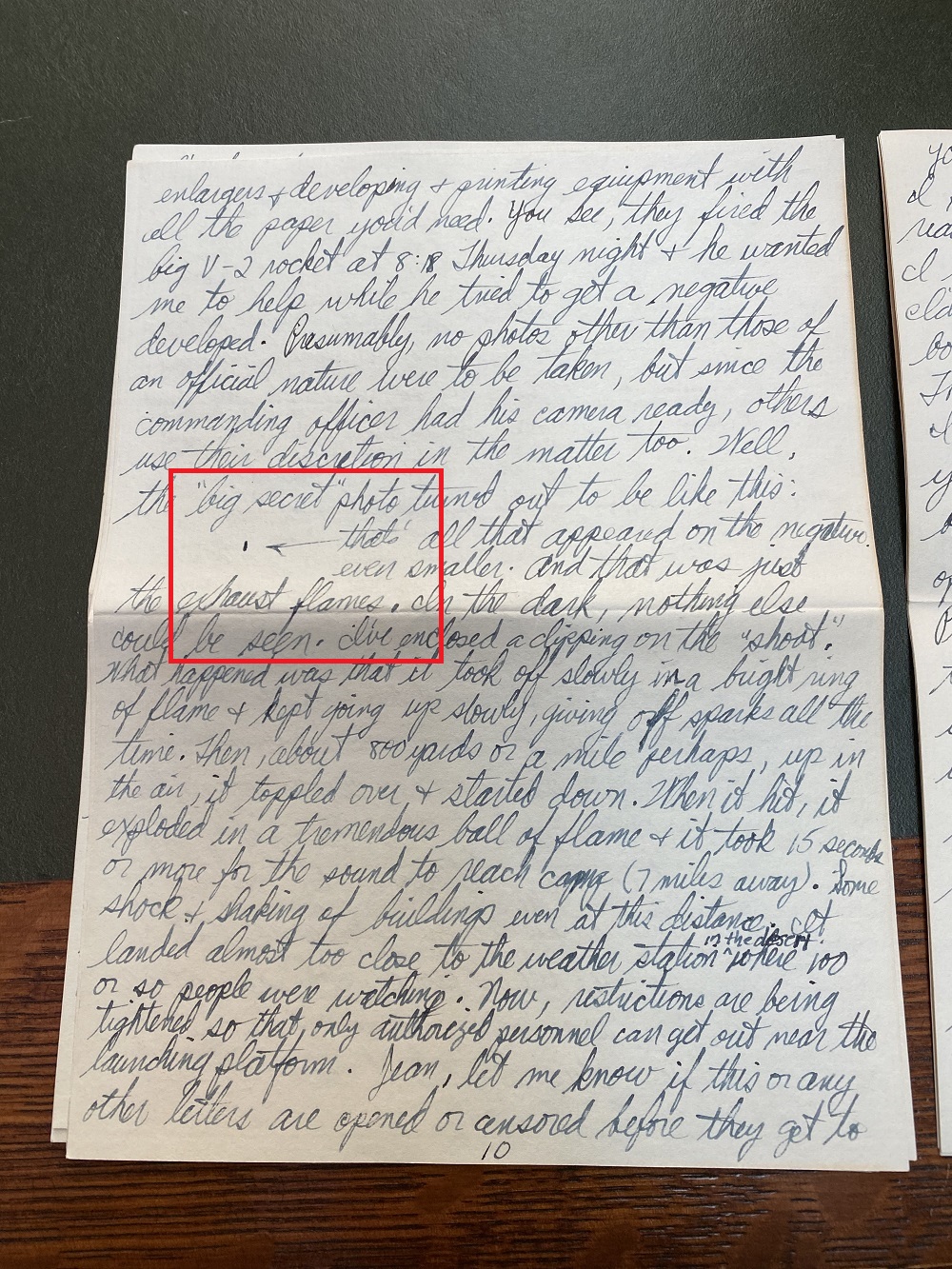

Although Stark did not offer significant recounting of the ins and outs of his work, he did give hints at the level of security clearance and intensity with which he was involved. In his description of this particular rocket launch, he explains how one of his supervisors took an unofficial photo of the launch, which was technically risky behavior. "Well, the big secret photo turned out to be like this: filled-in square on the page (1mm x 2mm) that's all that appeared on the negative, even smaller." [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951] Upon relaying this story, Stark recognized his proximity to sensitive information: "Jean, let me know if this or any other letters are opened or censored before they get to you." [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951] The letters do not indicate any censorship but the concern itself has historical importance.

The illustration in question can be seen on the page of the letter pictured above.

“Jean, let me know if this or any other letters are opened or censored before they get to you.”

Stark's letters do not comment on his patriotism, however, there were certain aspects of his work of which Warren was clearly proud. The box of photographs in the collection are a plethora of official photographs, labeled with "U.S. Army Ordnance," from the Armed Forces Day Parade on May 17, 1952. Presumably, Stark bought these photos from the Army archive; the backs of photos contain his handwriting, labeling the date of some images and pointing out his location in the group shots. A few photos have multiple copies in the box which might have been for distribution. In addition to marking his presence in a couple photos, he also indicates his presence in a newspaper clipping photo as well. He intended to show these moments to his family and wife back home - although he was not thrilled about his location or even his enlistment, he did have pride for the community in which he took part.

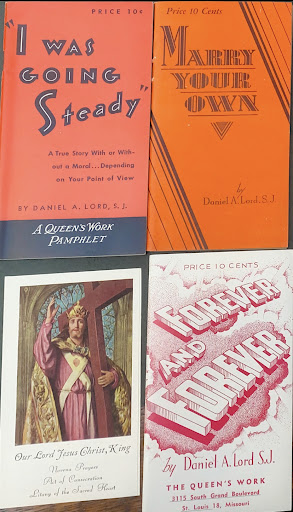

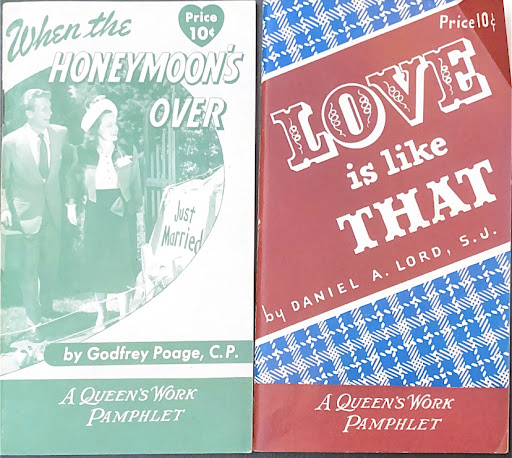

In his letters to Baldwin, it was not unusual for Stark to include little booklets. They always explained aspects of his Catholic faith. He encouraged Jean to save them "for our Catholic library, for our children." [Warren to Jean, March 30, 1951] He frequently mentioned the day-to-day future of their relationship as well. On a newspaper clipping detailing instructions on how to dance the "Waltz Box Step," he writes: "We'll practice this soon, I hope." [Warren to Jean, January 22, 1951] Throughout the letters, there is a sense that Stark feels he is living in a state of "pause." His service alone stood in the way of him reuniting with his wife, and real life could begin only when he returned.

The pamphlets reveal that Stark was also a practicing Catholic. He attended mass every day, even at his White Sands post. In his letters, he is very explicit about his faith and its influence in his life. He lived out his faith in quite public ways. Stark proudly described the way in which his peers noticed one morning that he missed mass. Relieved and definitely excited, he writes, "I've seen how others really do take notice of someone going to church... this other feller, Bill Meade, has asked me if he could go to Mass with me on Sunday, since he's Baptist + 'would like to learn a little bit about the other fellows' religion.'" [Warren to Jean, May 15, 1951]

“You know, I love you because you’re such a faithful Catholic.” [Jean to Warren, March 10, 1951]

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen popularized "prime-time Catholicisim" starting in 1952 as an "expression of homogenizing impulses within post World War II American religion."[12] The booklet materials which Stark included in many of his letters were often from a publisher called "Queen's Work," an operation which Daniel Lord, S.J., another American public religious figure, spearheaded. Lord wrote 228 pamphlets on the Catholic religion, selling over 25 million copies.[13] It is not clear whether Stark purchased these or received them through his church, but the pamphlets had such a strong reach that "during World War II, pamphlet racks were even found on Navy ships."[14] It was these commercial Catholic materials which Stark hoped to save for his posterity.

Stark does not describe his intellectual work in the letters, but at one point he explained that "no matter where I've been and whom I've met (MIT or Purdue or Notre Dame graduates notwithstanding) my Pratt education has been extremely thorough + fine." [Warren to Jean, May 8, 1951] Frankly, his Brooklyn pride appears even brighter than his national pride in the collection.

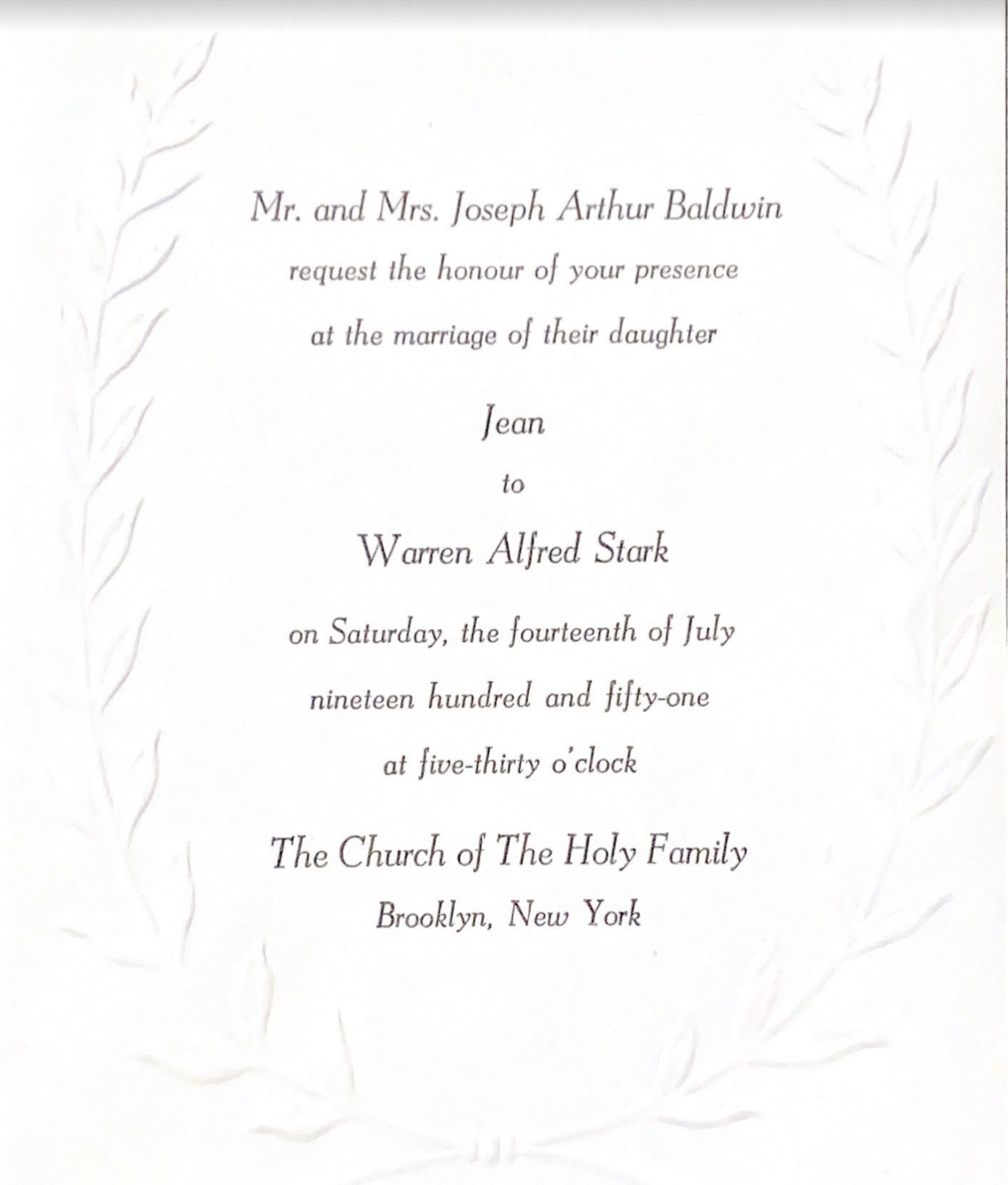

He and Baldwin concerned themselves over future savings. The Army provided allotments for spouses and families, so they benefitted on account of their relationship. As Stark hinted at his wedding date, he looked forward to the change when “[b]eginning July 14, the allotment goes into effect at the rate of $107 per month for 18 days in July (31-13). I must admit so far the Army has been pretty accurate in keeping financial records. ‘Supporting you’ sounds real good to me!” [Warren to Jean, May 8, 1951] Despite the sweet sound of money in this case, within this letter and others, Stark acknowledges that his wife might have to work for a bit longer in order to save cash. Women were less commonly in the workforce at the time, so it is notable that the soon-to-be Starks both needed to work for their household.

“I’m beginning to feel as you do about getting out of the Army. When you are discharged and [sic] I can quit teaching. Then I can be the housekeeper and wife I want to be, and you can do all the things you want to do. We have a wonderful life to look forward to together. It wouldn’t mean much alone. I really need you, Warren.” [Jean to Warren, January 21, 1952]

Planning their wedding proved to be a difficult aspect of their long-distance engagement. Stark remarked that he "never thought my marriage would be carried out like a mail-order business...” [Warren to Jean, May 20, 1951] Still able to offer a dash of wit, these were real challenges. Stark described frustrations with an omission of a Nuptial Mass, defined by the presence of one's wedding during a Catholic mass rather than an isolated blessing or another route, but he mostly assumed that the obstacle was Baldwin's non-Catholic family. Baldwin, however, cleared the air: "I told you I didn't want to be married at such a mass - besides the reasons I gave, I said there was something in me that didn't want it. In your letter you say that you have no part in the preparations. Well, what part do you expect to play?" [Jean to Warren, May 21, 1951] The post certainly must have provided ample time to cool off and regroup in a moment of anger or frustration. Indeed, the couple managed to mediate their conflicts rather well throughout the letters, but these emerging moments of frustration or anger are another part of their story.

"Honey, don't worry that I haven't any money. I'll be paid tomorrow + what I have left when I get paid again, I'll send home for the ring." [Warren to Jean, March 8, 1951]

Baldwin's voice in these wedding preparations is also important. Jean wrote confidently as she planned from New York, the wedding location, exclaiming through her prose, “Now I’m really getting excited! I’m glad we’re doing things right. It will be something we’ll never forget and all the memories will be beautiful and happy. It’s the kind of wedding I’ve always wanted. And I know you’ll be happy with my arrangements." [Jean to Warren, June 7, 1951] Trust was vital and still each letter writer confirmed that their love would remain strong regardless.

In addition to wedding uncertainty, Stark also did not know his future military placements. He wrote to Jeannie, asking "In case [Colonel Collins] offers me a job out in San Diego or some other city to work for some aircraft company + he says it will be OK for me to take you along, would it be OK for me to say yes?" [Warren to Jean, June 18, 1951] Rather than the type of work or location, Stark valued his wife's presence first and foremost.

"I never thought my marriage would be carried out like a mail-order business, but one never knows what future conditions will prevail.”

Despite his anticipation for the newlywed life, his attitude about the military never improved past acceptance. In the time when he was still looking forward to the wedding, he differentiated the immediate future and their lifetime after his military service. "Only 55 days more, so I'm anxious to get it over with + let the months pass by till I'm out of this Army for good. The years ahead will certainly be interesting!" [Warren to Jean, May 20, 1951] At this point, his flippant attitude towards his work might come as a surprise to only those unfamiliar with the collection. He indicates a sense of urgency completely unrelated to his position or the White Sands operations; this sense emerges immediately upon engagement with the material. Regardless of where he was drafted, Stark might have sent letters with almost identical content and concerns. In his writing, his heart and mind are unified in their focus on his love and relationships. He reaffirms his love for the woman who becomes his wife and cares deeply about the way she understands him.

Warren A. Stark married Jean Anne Baldwin on July 14, 1952. He ironically received a copy of his own wedding invitation in the mail, but his letters leading up to the day are increasingly filled with excitement and expectation. His letters also indicated that he went on leave for the wedding and a few months after, but he returned to his White Sands post eventually. After his time on leave ended, he continued to send pamphlets for their future library, but also for themselves, titled "Sex and Marriage" and "When the Honeymoon's Over." Warren eventually received a more favorable placement in Camden, NJ, although the letters indicate its temporariness. Stark was still subject to move locations for his work until his discharge; however, he did make some long-term decisions during this time. The couple bought a house in Amityville, New York, the town on Long Island where Jean had begun to grow roots and lived, waiting for Stark to end his military service in 1952. After his service, he attended New York University to earn a graduate degree in Mechanical Engineering and worked as an engineer until his retirement. Jean Anne Stark preceded Warren in death, passing away in 1999.[15] Warren Stark passed away in 2011. [16]

The Warren Alfred Stark collection has unexpected content, lessons, and research potential. It is also very personal, revealing the intimate thoughts and feelings of a long-distance relationship which, during the span of the letters, became a union for life. Stark was an engineer, drafted along with many others of his generation during the Korean War. Rather than fighting on the front lines, he remained on American soil. That being said, the White Sands military base location was significant, so while Stark was always aware of his distance from his wife and home, he was at the center of very important and consequential military rocket science. The more cultural side of his letters, his Catholic values and relationship expectations and desires, speak to another facet of researchable material in this collection. The culmination of these elements in his wedding and his frustrations and excitement throughout its planning are endearing. Overall, it is safe to say that the contents of these letters confirm the nobility and humility of Warren Stark, as well as his wife Jean. The rich narrative of this collection should be remembered.

Endnotes

[1] The content which comes from Warren Stark or those in his life is directly quoted from the letters in his collection: Warren Alfred Stark Papers, 1947-1952 (mostly 1950-1952), Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

To avoid repetition, the letters will be cited throughout the piece indicating sender, recipient, and date. They are found still in their envelopes within the boxes of the collection.

[2] Jim Eckles, “A Not Very Good White Sands Football Team Overcame Social Injustice & Set an Example,” (“Hands Across History” newsletter, Vol. XIII, Letter IV, White Sands Missile Range Historical Foundation, 3). https://wsmrmuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2017-11.pdf.

[3] Michael Welsh, “Chapter Five: Baby Boom, Sunbelt Boom, Sonic Boom: The Dunes in the Cold War Era, 1945-1970,” White Sands Administrative History, last updated 22 January 2001. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/whsa/adhi/adhi5.htm.

[4] “Warren Alfred Stark,” Legacy.com, 14 November 2011. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/northjersey/name/warren-stark-obituary?id=22561263.

[5] “Tau Beta Pi Collegiate Chapters,” Tau Beta Pi: The Engineering Honors Society, Tau Beta Pi Association. Last accessed 3 May 2022. https://www.tbp.org/off/chapterList.cfm.

[6] National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for New York City, 10/16/1940 - 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147.

[7] Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/194188690:2238?tid=&pid=&queryId=379ea60690c7e5fa84bd46723aa4f6ab&phsrc=XAW4&phstart=successSource.

[8] “White Sands National Park History,” National Park Service, last updated 16 April 2022. https://www.nps.gov/whsa/learn/historyculture/white-sands-national-park-history.htm.

[9] Welsh, “Chapter Five.”

[10] “White Sands National Park History.”

[11] “Park Statistics,” National Park Service, last updated 15 March 2022. https://www.nps.gov/whsa/learn/news/parkstatistics.htm.

[12] Welsh.

[13] Anthony Burke Smith, “Prime-Time Catholicism in 1950s America: Fulton J. Sheen and ‘Life Is Worth Living,’” U.S. Catholic Historian 15, no. 3 (1997): 57, accessed 3 May 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25154593?seq=2.

[14] Stephen Werner, “Daniel A. Lord, SJ,” American Catholic Studies 129 no. 2 (2018): 39, accessed 2 May 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26585129.

[15] Werner, 47.

[16] Ancestry.com. U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007.

[17] “Warren Alfred Stark,” 2011.