Mr. and Mrs. Bookman: The Indian Service Library Bookmobile in Southern Arizona

By: Austin Davis '23

Access the digitized photo album via Princeton University Library.

Motion picture service for Phoenix Indian school students Saturday night, April 9, was titled, ‘Make a Wish.’ Bobby Breen, the young singing star, headed the cast of players in this picture. Besides the regular feature, a Donald Duck comedy created laughs for the audience. [1]

The entertainment on April 9, 1938, was no abnormality at the Phoenix Indian School. Like many other Saturday nights, the faculty pulled out the movie projector, flipped it on, and showed the students various films and shorts. Films drew on a range of topics to enthuse viewers: the Disney cartoons of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse, Hollywood Golden Age films of the likes of Katharine Hepburn and Fred Astaire, and even demonstrations of basket-weaving techniques of the Pima and other local indigenous peoples. On nights such as these, schoolchildren at Phoenix Indian School were dazzled by the brilliant displays of movies, cartoon shorts, and documentaries.

Short references such as these in the Phoenix Redskin, the school’s student-run newspaper, concealed the infrastructure that supported these joyous motion picture services. Each article conveyed the same information: the films shown and the audience response. Few made mention of “Mr. Bookman,” the bookmobile driver who shuttled these cultural materials between the Phoenix Indian School and approximately ten rural day schools on the reservations in southern Arizona. Bestowed the name “Mr. Bookman” by the children for his work, he carried in the truck films, books, victrola records, cultural exhibits, and even the movie screening equipment itself.[2] Emblazoned with the words “Indian Service Library and Motion Picture Service” and "U.S.I.S. Traveling Library," Mr. Bookman’s truck facilitated the careful exchange of educational and recreational cultural material for indigenous children.

During these routine journeys to far-flung reservation schools, Mr. Bookman—an absentee Shawnee man by the name of Pierrepont ‘Pierre’ Alford—and his wife Dorothy prolifically documented the trips with likely hundreds of vernacular photographs, carefully documenting in pen the location, time, date, and elevation of each. Generally, it appears it was likely Dorothy Alford who did the annotating; the consistency of the handwriting across all the photos, as well as the use of the more informal 'Pierre,' hints that the note-taker knew the Alfords well and was likely at all these sites. Annotations added later in pencil—either by the Alfords or another party—demonstrate the extent of the collection, seemingly amounting to more than 250 photographs. At Princeton, only forty-one prints survive, but these photos captured a variety of scenes: the teachers and classes the Alfords visited, the arid landscape of Arizona, and occasionally the photographers themselves.

In effect, the Alfords chronicled one aspect of the Indian New Deal. Like its more national namesake, the Indian New Deal sought to economically empower the country’s indigenous population through extensive social programs. Under the supervision of the Indian Affairs Commissioner John Collier, the government agency largely focused on the reappropriation of native lands to facilitate economic development. However, his office also embraced a holistic educational program to rehaul the existing Native American school system. Reforms included the publishing and dissemination of materials in indigenous languages; the expansion of the day school system; and new summer training programs. As such, these efforts sought to make indigenous communities both self-reliant and enmeshed in their original cultures.[3] This complex program, Collier believed, enabled the reservations to bring the Native American back to life. In his 1938 annual report, he wrote:

The last fiscal year witnessed a maturing of program, a great quantitative increase in Indian participation, the correction of many errors in detail in organization and procedure, the solidification of that program which holds the future of the Indians. The Indian Service and the Indians alike become more consciously the possessor of a new goal, of the technics appropriate to the new goal, and of a spirit of victory. How far off that goal is, how many the shortcomings… But [the report’s] main message is the true one, that Indians, physically and spiritually, are coming into their own.[5]

The reservation day schools of southern Arizona often lacked the resources to provide a quality education to tribal children. Located in the interior of these reservations, the simplest way to may of these schools was by automobile over winding, unpaved roads. In 1932, for instance, the Vamori Day School on the Papago (now Tohono O’odham) reservation was over eighty miles away from the nearest train station in Tucson.[5] The remoteness of these schools also meant they lacked electricity or water; otherwise, the arid environment created troublesome conditions for such infrastructural hookups. As these day schools educated more and more children—the number of pupils tripling between 1933 and 1941—it was the mission of the Office of Indian Affairs to fill these severe gaps of educational material at these schools.[6]

In order to fill these gaps, in the fall of 1936, the Office of Indian Affairs proposed the Indian Service Library of Southern Arizona. This library service would circulate books between the Phoenix Indian School and the reservation day schools, all of which would be connected by a bookmobile service. Additionally, this plan called for an extensive library system for all schools in the Southwest, envisioning an extensive catalog of more than 18,000 volumes. In the announcement in the Redskin, the student reporters outlined how this new approach figured into the mission of the Office of Indian Affairs to make available reading materials for indigenous schoolchildren in the region:

The traveling library plan, including the visual education program, is an entirely new venture in the Indian Service, and the Phoenix school library plan is entirely experimental. If it proves successful the plan is to be carried out in the other Indian schools in the United States. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs believes that it will be a more beneficial way of getting more education to the Indians on the reservations.[7]

To meet the expectations of this proposed program, the Phoenix Indian School—the soon-to-be-hub of the new library system—shifted operations at its own library. Expansion of the school library required both new staff and space to accommodate the growing number of books. In 1936, carpentry students expanded the library into an adjacent classroom, constructing new shelving for the new arrivals.[8] Additionally, to help the librarian, Nettie Willis, to select these new arrivals, catalog them, and prepare for them for the book truck, the school suggested the hire of an assistant librarian. A later article in the Christian Science Monitor would explain that the school also relied on workers from the Works Progress Administration; however, it is likely that it instead received some aid from the Civilian Conservation Corps, as records from the school superintendent, R.M. Tisinger, show representatives from the New Deal agency helped with the selection of film.[9] To become the library of the Southwest, it had to have the resources to match.

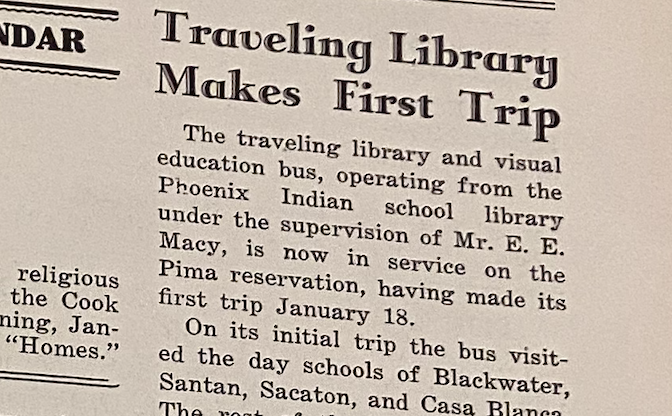

In early 1937, the bookmobile made its grand debut. On its maiden voyage, it traveling to the schools of Blackwater, Santan, Sacaton, and Casa Blanca, carrying 1,000 books, 100 phonograph records, 500 stereographs depicting native life on reservations, and the equipment to show these materials to students. Above all, the truck’s motor could power projectors to screen films at the day schools, thus mitigating the complications presented by the region’s weak infrastructure. Today, we have no photographic record of its very first trip. Likely, this is because the driver was not yet Pierrepont Alford and his wife; instead, Ezra E. Macy, the visual educationist of the Phoenix Indian School, commandeered the truck on its first trip along meandering desert roads.[10]

His tenure, however, was short-lived. By the fall of 1937, Tisinger and other leaders at Phoenix Indian School had discussed reassigning Macy in favor of Alford.[11] Although they gave no reason for his reassignment, prior professional descriptions of Alford attested to his scholarly aptitude and versatile skillset. For instance, an inspector from the Pima Agency wrote in 1927: “[Alford] is a man of remarkable information and a perfectly extraordinary use of the English language… he has the vocabulary of a scholar and marked student.”[12] Perhaps for similar reasons, the Phoenix Indian School found him a valuable worker for its new library system. In an announcement to the day school of southern Arizona, the school declared the new changes to the system, including the assignment of Alford and his wife to the role of the traveling librarians:

We have just completed overhauling and enlarging our traveling bus, and we are purchasing a new 35 m.m. sound picture machine to be installed in the bus. Mr. and Mrs. Alford will be making trips soon with this bus and picture machine to various school communities on the reservations, and it is hoped that you will avail yourselves fully of the opportunity for them to serve you. Our Phoenix library of 15,000 volumes is available for your use through this service. Any suggestions of how we may improve this service will be appreciated by Mr. and Mrs. Alford.[13]

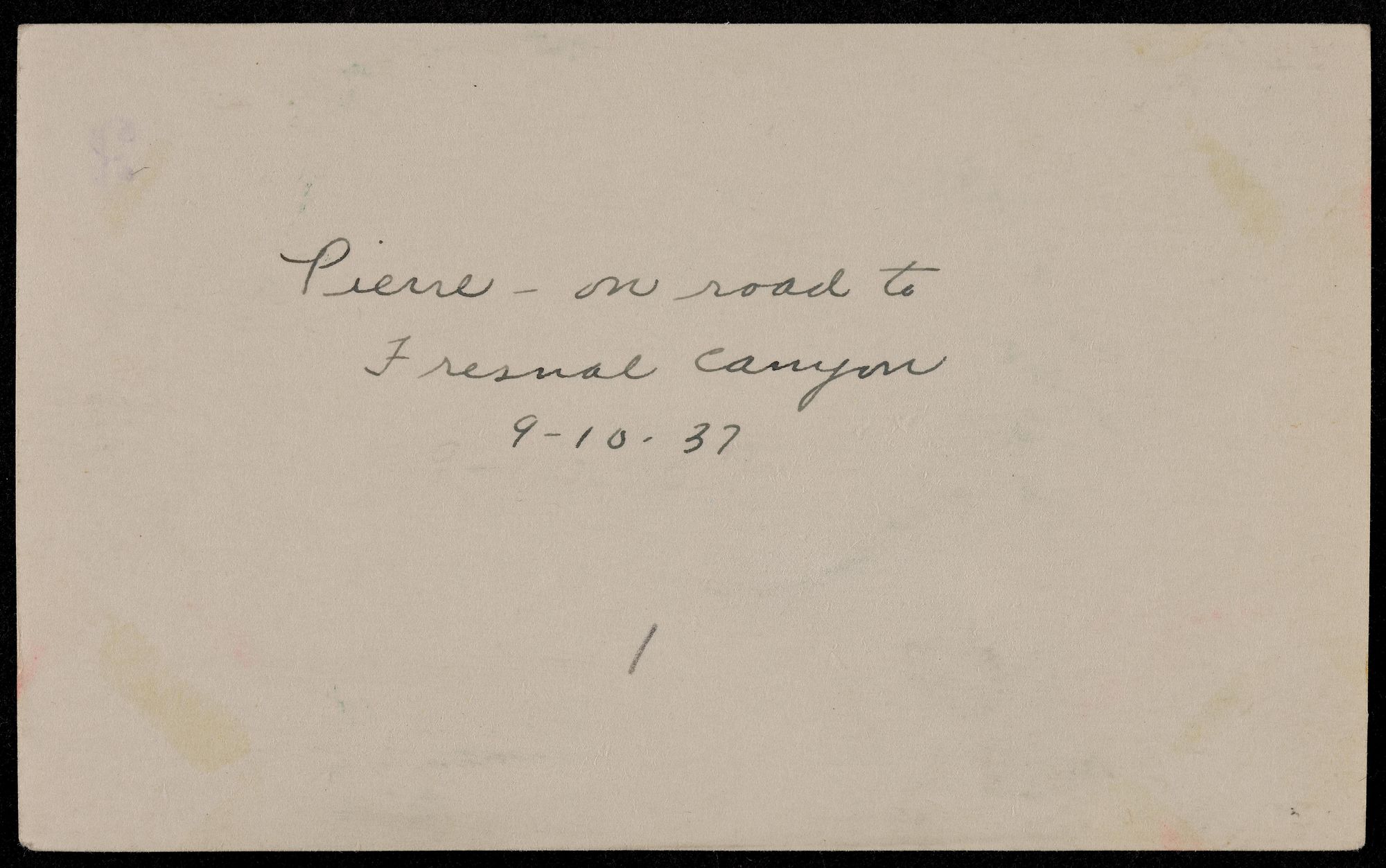

Alford and his wife, however, had already begun their journeys. Their photographic record had long proceeded this announcement; on September 9, 1937, at Fresnal Canyon, an unnamed photographer—presumably Dorothy Alford—snapped a picture of Pierre sitting on the bus on Kodak verichrome film. On the back, in neat cursive script, the photographer had written: “Pierre—on the road to Fresnal Canyon.” Not only does the shortened version of his name imply it was likely his wife who had snapped the photograph and written the annotations, it confirms that they had likely already begun visiting schools. Nestled in the Baboquivari Mountains of southern Arizona, the canyon was situated on the edge of Papago lands, in close proximity to the day schools at Vamori, Sells, and Topawa. Although these earliest pictures depict natural scenes, it is probable the pair had already begun their routes.

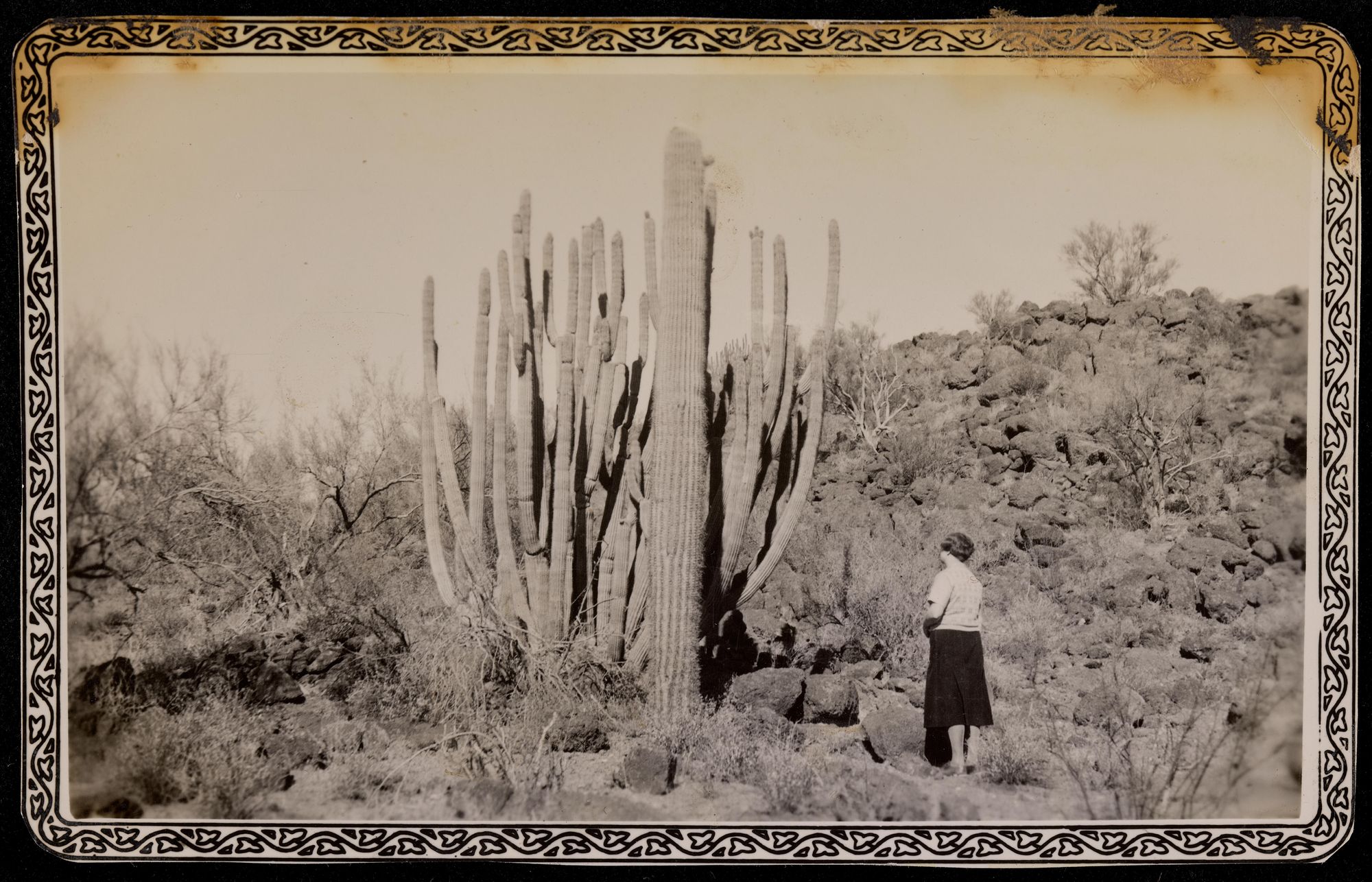

The collection of photographs could be split into three different categories. First, there are depictions of the day schools, often focusing on the pupils and staff of those institutions. Second, there are photos that depict the surroundings, which include both natural scenery and depictions of rural living. Third, there are photos of the Alfords themselves. These photos blur the lines between some of the categories. In some, Pierre or Dorothy sits pensively among the sparse foliage of the arid landscape or on the stairs of the bus, the other likely snapping the photo. Another time, Pierre sets up the projection for a screening at Kerwo Day School. Again, these categories might not represent the full breadth of the collection’s themes; after all, these photographs are likely a selection of the hundreds the pair took during their journeys in southern Arizona.

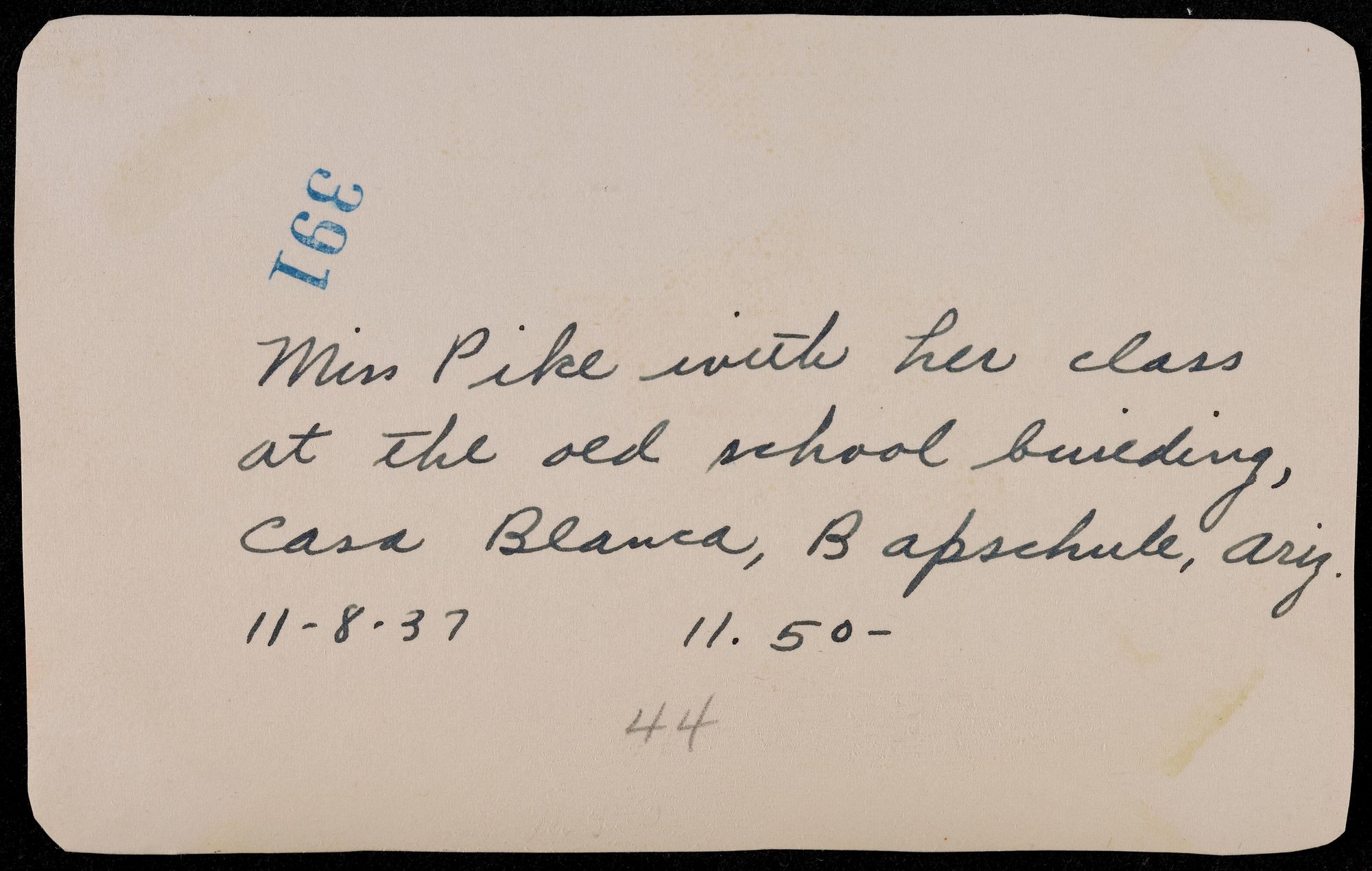

Many of the photographs document the day schools, with a focus on the faculty, staff, and students of those institutions. These photos that depict people are remarkably similar in each iteration. Typically standing in front of some staff living quarters at the school, the teacher, housekeepers, and pupils pose for the camera. The Alfords rarely diverge from this pattern, often photographing the same class of students mere months later during another visit to the school. For example, at Santa Rosa Ranch school, the pair captured Miss Katherine Shorten with her class twice—once on the playground and another time in front of her quarters. Like the data collected on the back of these photos, the repetition of these poses—across time and space—suggests a standardization to the form and type of material they collected from these schools. As such, the duo both proved the bookmobile’s presence at these sites but connected it to the lives of the teachers and students whom its material supposedly served and assisted.

Through the lens of these school photographs, one of the possible intentions of these photographs becomes increasingly clear. Since the bookmobile was originally proposed as an “experimental” solution to the problems of rural education on the reservation, the successive photographs of children with their teachers suggest the success of the Alfords’ mission in providing pupils with reading material. When we look at the photographs of children reading at Phoenix Indian School (such as the one at the beginning), for instance, the purpose becomes even clearer. Children, quietly reading on the steps of the bus, become the models for the success of the library in its stated goals. It shows active and engaged subjects, benefactors of the ambitious education plans of the Office of Indian Affairs to educate future generations of self-sufficient indigenous communities.

Regarding the content these children were likely reading, the Redskin provides a helpful look into the bookmobile’s contents. While it carried hundreds of volumes, the push under the Collier administration to both encourage economic development on the reservations and reinforce tribal identities becomes quickly apparent through the reading and film selections. The librarian Willis’s acquisitions for the library service reflect this impulse, in which the newly acquired literature spans a range of genres to not only teach children to read but convey these then-important themes. Works included histories such as Julia Davis’s No Other White Men, an account of the Lewis and Clark expedition, or agricultural treatises such as McIntosh’s First Problems of Agriculture. Films reflected this effort, too: while Disney cartoons were popular with young viewers, the bookmobile similarly carried shorts on basket-weaving techniques, irrigation, and other practices.[14] The library was both diverse and growing, intending to convey key values to the day schools of Arizona.

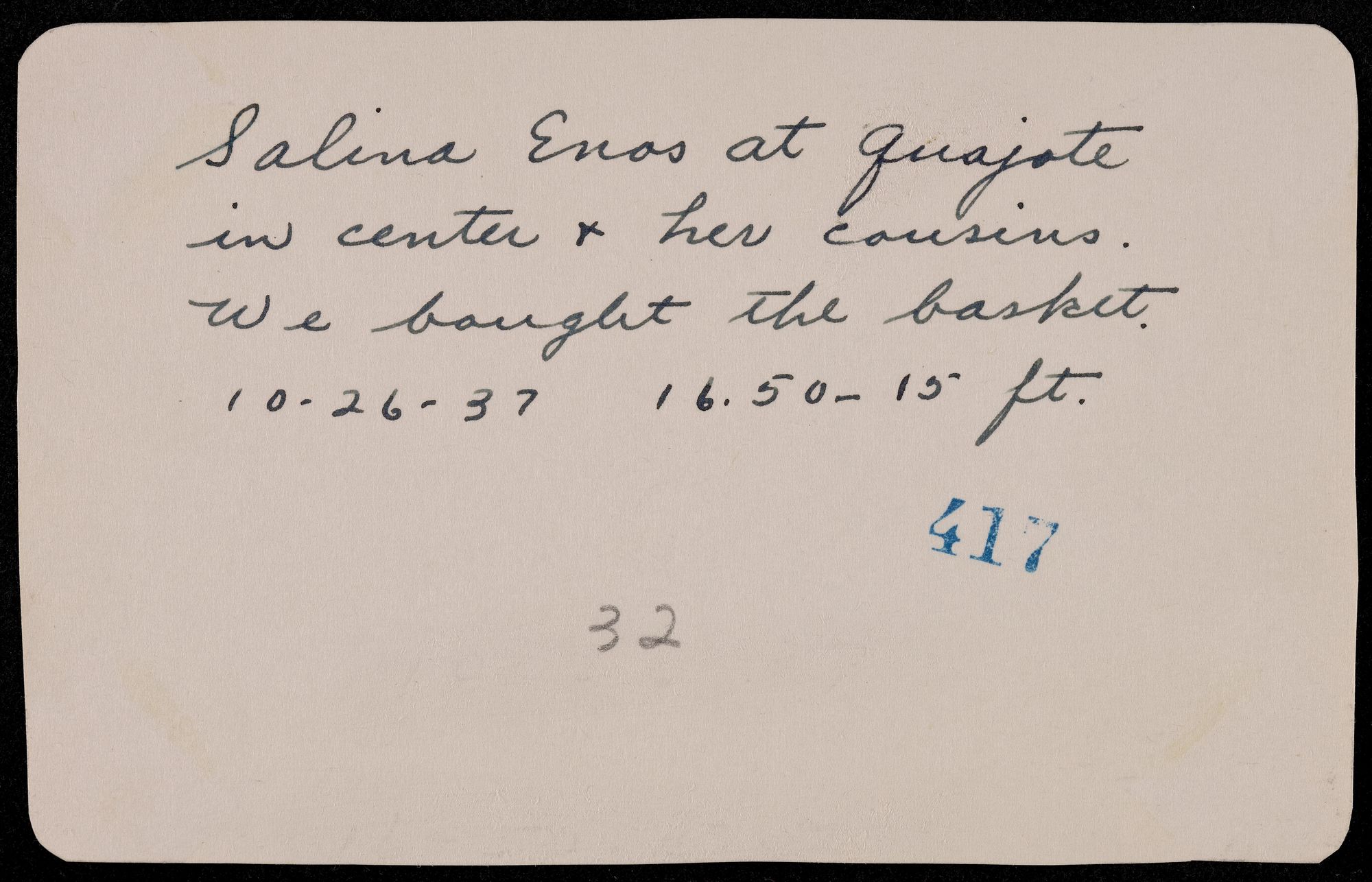

Books and films were not the only items exchanged by the traveling library. The Alfords also carried cultural exhibits and vocational training materials, which touched on a wide breadth of topics: basket weaving, ink making, cattle raising, among others. But this exchange was not a one-way street; as much as the students and teachers at the day schools consumed the materials provided by the bookmobile, the Alfords obtained items from these people, too. At Quijotoa, the Alfords “bought” a basket, presumably from the three Papago housekeepers they photographed at the school, only one of whom—Salina Enos—is named. Notably, the basket’s geometric design resembled those of the Papago or Pima, the tribes which the bookmobile primarily served.[15] Posing the three women in an arid landscape, the couple showed one of the housekeepers holding the basket. The deliberate decision to pose the three women from the basket showed from who—either these people or the more general tribal population—from which the Alfords sourced the basket.

No doubt, however, was the traveling library in its initial years a success. As the Redskin recalled in May 1941, the school library had seen extensive use from the growing network of day schools which it served. Not only had the library been expanded again, this time with the addition of an elevator “for the convenience of the traveling librarian,” raw numbers demonstrated the success of the once experimental practice:

The library still grows. Seven hundred and sixty new books were added this year, bringing the increase in ten years from 4500 to 17000. The loans are approximately the same, this year 9165 to students… The traveling library was added in 1936. Last year it served 23 day schools loaning books, phonograph records, mounted pictures and posters to teachers, which totalled 36751 loans. In turn teachers loaned the books to many students.[16]

By the time the Alfords left the bookmobile service in the mid-1940s [17], bookmobiles had become a national phenomenon. While I cannot identify the fate of the Library of Southern Arizona and its bookmobile, the WPA developed an extensive bookmobile system to connect both urban and rural readers with cultural material. Although this system was liquidated during the Second World War, state and local governments picked up the slack in the post-war era.[18] Even to this day, the Tohono O’odham nation funds bookmobiles for residents of Pima County, in which their reservation mostly resides.[19]

However, the intentions behind these photographs do not feel purely institutional or governmental. Surely, the Alfords were agents of the Indian Service, documenting the work they performed on reservation schools. But the two other categories of photographs speaks to the impulse to catalog the impact of their work. While one could easily compose a travelogue from their extensive collection of important data points—dates, times, locations, elevation, and even plant life (one photo has them measuring plants!)—these photographic observations of natural and artificial surroundings do not square perfectly with this neat definition.

The photos of landscapes and the Alfords themselves suggest a more personal impulse. This was not merely work to them, but something deeper. As both a seasoned employee of the Indian Service and a member of what one could call an “Indian Service family” (both his brother and father were also employed by the Office of Indian Affairs), this work likely represented for Pierre Alford the culmination of his career.[20] At schools like the Phoenix Indian School, he had educated children about blacksmithing or wood shops; however, he rarely had the opportunity to touch the lives of so many children from one school. Entering his 60s in the 1940s [21], Pierre and Dorothy likely had the time to reflect on their professional and personal trajectories to that very point as they traversed the dusty roads of the Arizona reservations.

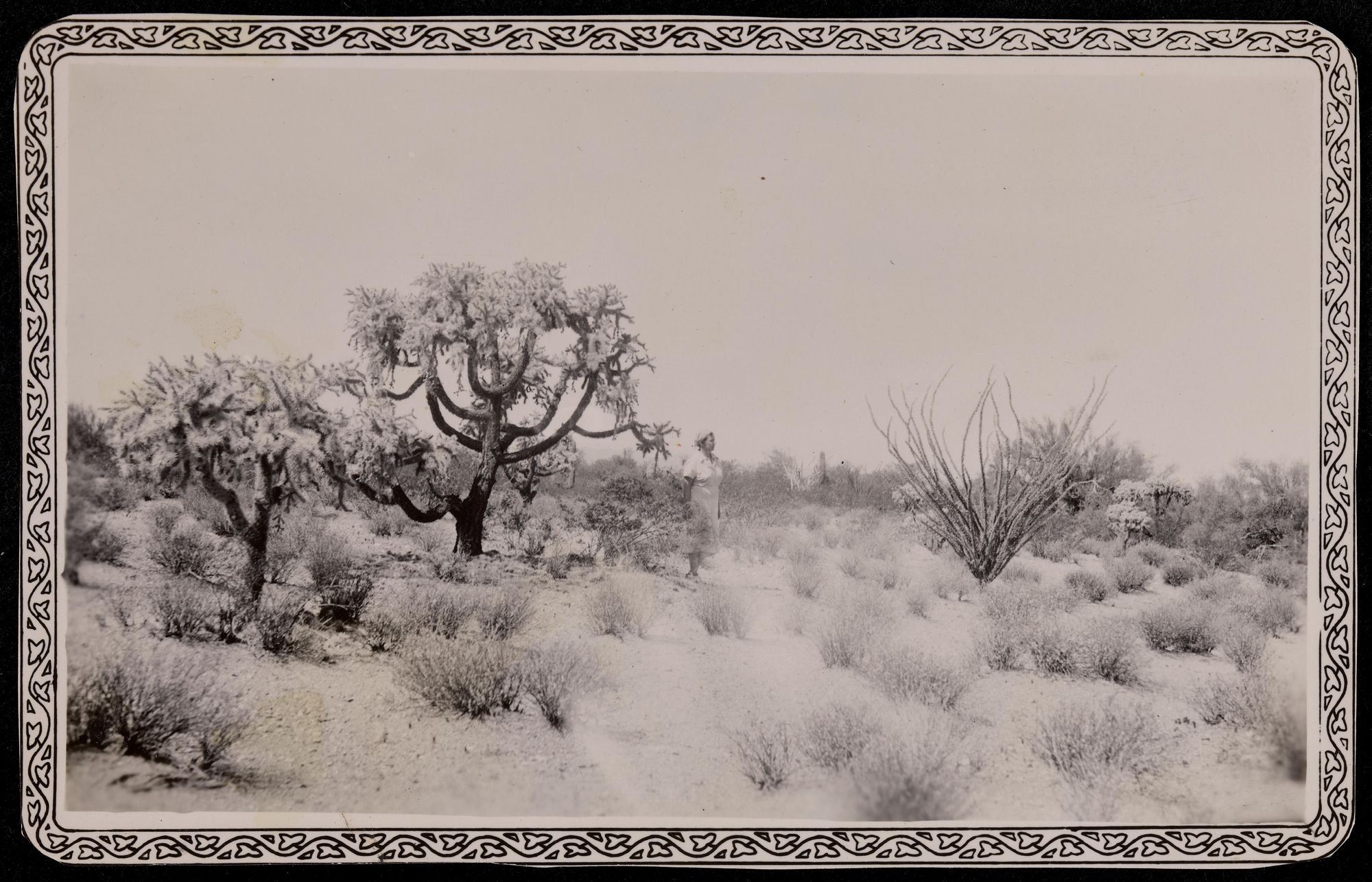

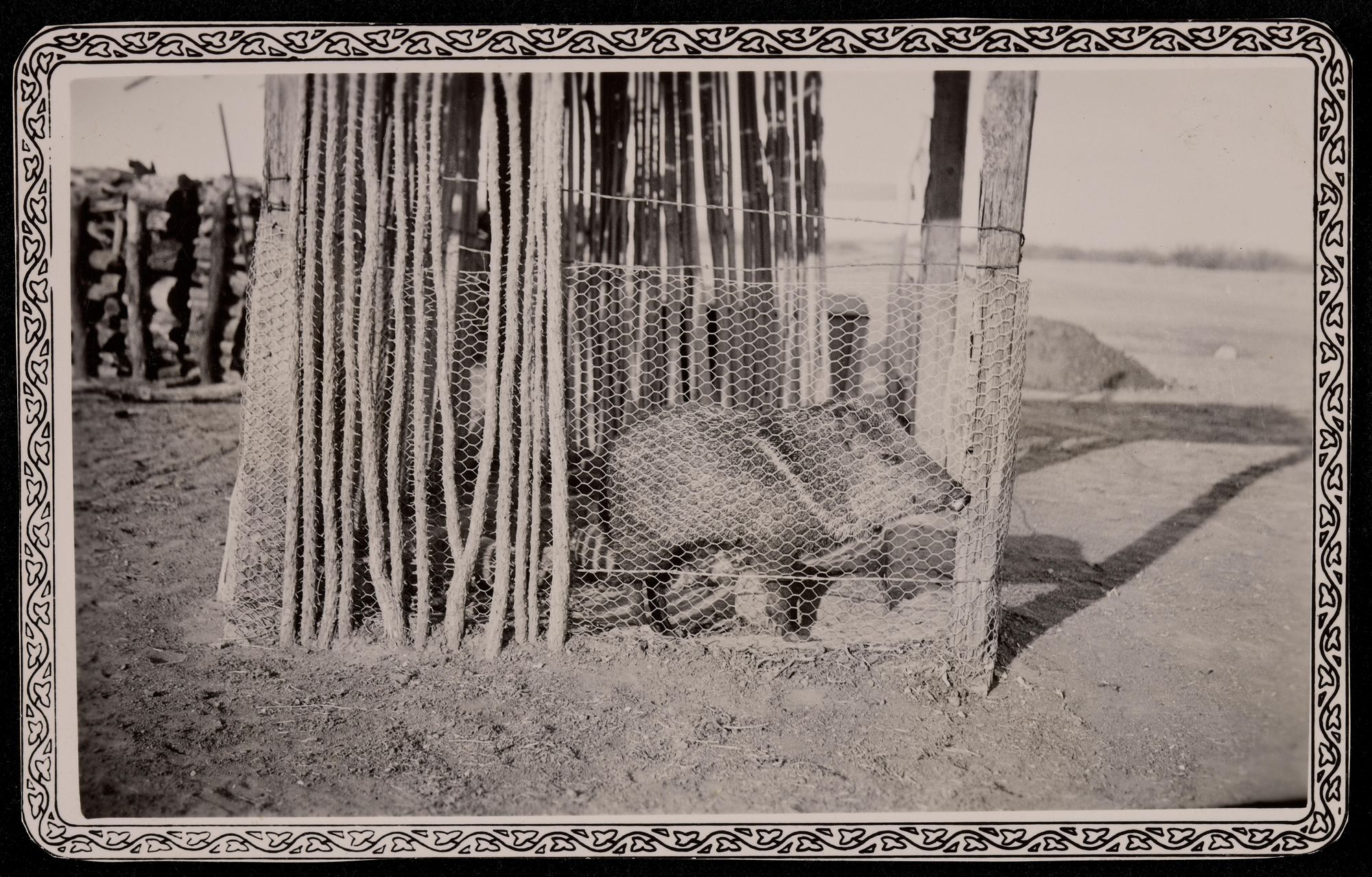

As they encountered the landscapes and people of southern Arizona, the Alfords made use of their transportable camera and the large quantity of verichrome film to capture any scene they came across. They could not only whip out the camera to get shots of schoolchildren reading, but also to get pictures of sites they passed and witnessed. At San Miguel, the couple saw a “comely” Native American village. At Troup’s store, they saw a javelina they might have found cute or funny, calling it a "wild pig." Looking at the mountains, the ruins of forts, and the road signs, the couple lost themselves in a natural environment that had necessitated the existence of such a program in the first place. One day, on January 9, near Kerwo, Pierre and Dorothy stopped the bookmobile, walked out amid the cacti and hillsides, and took pictures. In them, they look small in comparison to the vastness of the landscape. Walking off into the road and into the desert scrub, Pierre and Dorothy actively reflected on their lives up to that point through their camera. Having both worked in or near the schools, these journeys served as the metaphorical documentary culmination of their work.

These photos, then, had a dual purpose. Undoubtedly, these photos were a part of an effort to document the work of both Pierre and Dorothy Alford, showing the impact of the bookmobile on indigenous communities that they served. But this does not account for the landscape photographs or the occasional presence of the photographers in the photos themselves. These photos were likely personal mementoes that highlighted this journey through the deserts of southern Arizona, in which this couple performed for years what they found to be a service to these communities. In all, then, these photos are not only the product of the bookmobile, but ways to remember the years spent in the deserts for both Mr. and Mrs. Bookman.

[1] “Student Activities,” Phoenix Redskin, April 15, 1938.

[2] “Book Truck Serves Indian Schools in Southern Arizona,” Indians at Work 5, no. 9 (May 1938), 27.

[3] Jon Reyhner and Jeanne Eder, American Indian Education: A History, second edition (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017), 230-247.

[4] John Collier, “Office of Indian Affairs,” 1938, in U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs: Annual Reports 1938/39-1953/54, reprinted from the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, 23-24.

[5] Office of Indian Affairs “Routes to Indian agencies and schools, with their post office and telegraphic addresses and nearest railroad stations, also airport schedule,” Department of the Interior, July 1, 1932, 38.

[6] Margaret Connell Szasz, Education of the American Indian: The Road to Self-Determination Since 1928 (University of New Mexico Press, 1999), 61. Also see Rehyner and Eder, 245.

[7] “Service Extended by School Library,” Phoenix Redskin, September 29, 1936.

[8] “More Shelves Installed in Indian School Library,” Phoenix Redskin, October 20, 1936.

[9] R.M. Tisinger to Paul L. Fickinger, January 9, 1937. For the Christian Science Monitor article, see: “Library Takes to the Train,” Christian Science Monitor, November 14, 1939, 16.

[10] “Traveling Library Makes First Trip,” Phoenix Redskin, January 26, 1937.

[11] In documentation evaluating Macy’s performance, school leaders wrote: “Recommendation has been made for the transfer of Mr. Macy. Recommendation also has been made for the transfer of Mr. Pierrepont Alford, shop teacher at Valentine, to this position.” See R.M. Tisinger to Paul L. Fickinger, June 24, 1937, 3.

[12] H.H. Fiske to Hubert Work (Secretary of the Interior), March 31, 1927, 72.

[13] “To All Superintendents and Principals in the Southern Arizona Area,” Phoenix Indian School, December 20, 1937, 1.

[14] For an example of the books that the library possessed, see this example from the Redskin: “School Library Sponsor ‘Spelling Bee,’” Phoenix Redskin, December 14, 1940.

[15] Yujji Miyahi, “Tohono O’odham Basketry: One of Sells’ richest preserved traditions,” El Inde, September 18, 2015, https://indearizona.com/tohono-oodham-basketry-one-sells-richest-preserved-traditions/, accessed April 19, 2022.

[16] “Library Notes,” Phoenix Redskin, May 15, 1941.

[17] By 1950, the Alfords had moved to Los Angeles, CA, according to voter rolls. As a fun fact, both were registered Republicans. See "California, U.S., Voter Registrations, 1900-1968," database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/), entry for Pierrepont Alford and Dorothy Alford.

[18] Martha H. Swain, “A New Deal in Libraries: Federal Relief Work and Library Service, 1933-1944,” Libraries & Culture 30, no. 3 (Summer 1995), 265-283. For some information on bookmobile services in general, see: “Mobile Libraries: Culture on the Go,” The National Archives, April 14, 2022, https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2020/04/14/mobile-libraries-culture-on-the-go/, accessed April 19, 2022.

[19] “Library bookmobile gets makeover,” Pima County Arizona, July 29, 2016, https://webcms.pima.gov/cms/One.aspx?portalId=169&pageId=269317, accessed April 19, 2022.

[20] For some of Pierre Alford’s occupational history, see: B.P. Six to the Charles H. Burke (Commissioner of Indian Affairs), April 25, 1928. “Generations of Service,” Indians at Work 6, no. 6 (February 1939), 24-26. “Teachers’ Association Joint Meeting,” The Native American 29, no. 1 (January 1929), 20.

[21] See “1900 US Federal Census,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/), entry for Pierrepont Alford.