"Diary of a Homely Old Sinner": William Courtenay, Fannie Patterson, and the Fort Berthold Papers

By: Katie Bushman '22

Access the digitized William Courtenay Papers via Princeton University Library.

In a collection of documents from a clerk at a nineteenth-century Indian Agency, an unexpected thread emerges: a love story.

"I wish you were here to see the primroses in the evenings—they are a perfect mass of bloom... The pansies you inclosed are very pretty, but I don’t require them to give me 'thoughts' about you—you are all the time my pansy."

It was May of 1881, and already the Dakota weather was sweltering and the mosquitoes were merciless—"thicker than a man's friends when he falls heir to a big legacy!" as William Courtenay put it in a letter to his wife, Fannie. The two had been married for less than a year, but William now found himself alone in the couple's home at the Fort Berthold Indian Agency after Fannie had fallen ill and returned to her family in the East for a few months to recover.

"I do hope, darling, that you are improving in health and gaining flesh," William wrote. "If this weather continues I’ll melt away & nothing will be left but the wick; I would like to see you fat and rosy and a happy little wife."

Though only two of the many lengthy letters William wrote to Fannie survive, their story threads throughout the William Courtenay Papers, housed at Firestone Library. Through a variety of documents, the researcher glimpses a series of vignettes illustrating life at a nineteenth-century Indian Agency.

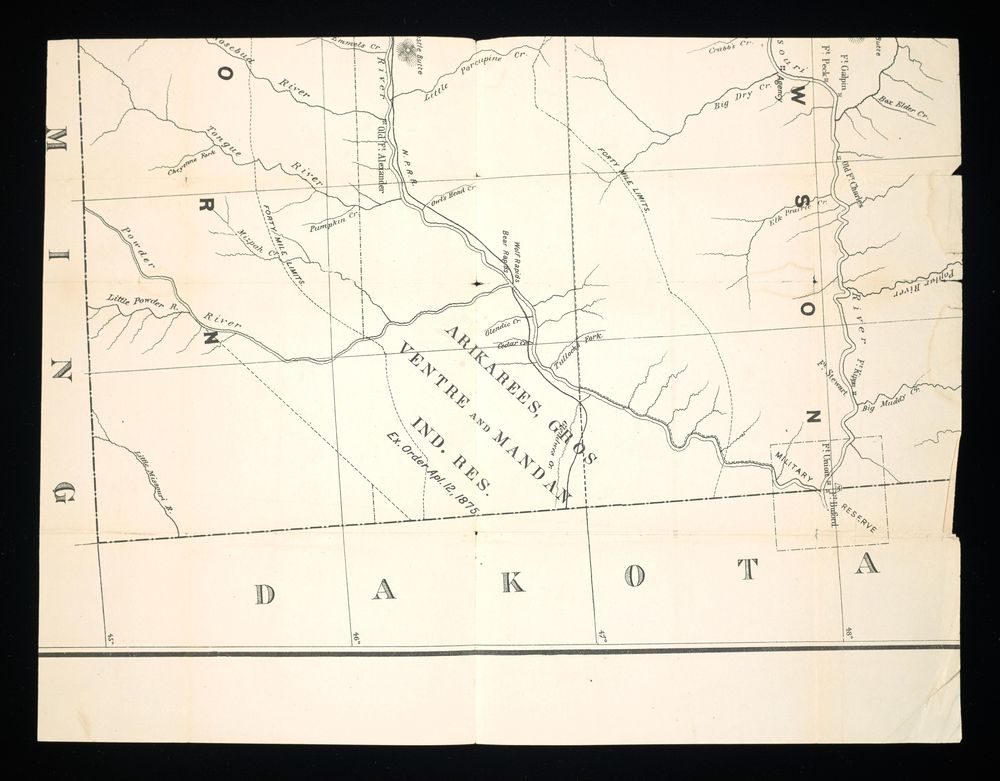

The first part of the Courtenay collection relates to the Courtenays’ tenure at Fort Berthold. It consists of maps of the reservation, a book of postal records, payroll receipts, sheets from Hidatsa language and sign language dictionaries, a certificate of appointment, and letters recommending William Courtenay for the agency position. It also includes several testimonies and writings by members of the Three Affiliated Tribes themselves. These include legal statements, testimonies, and letters to both of the Courtenays.

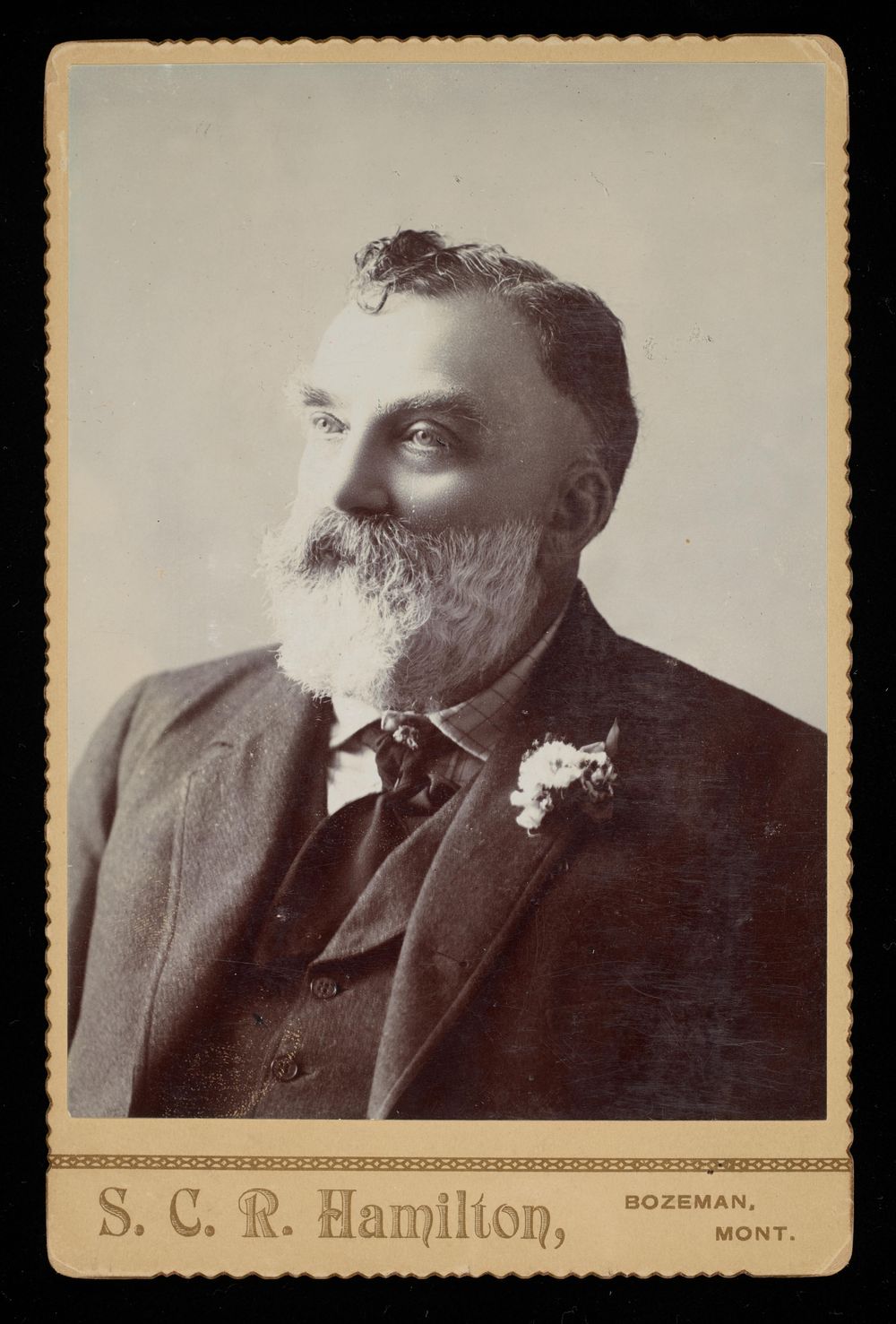

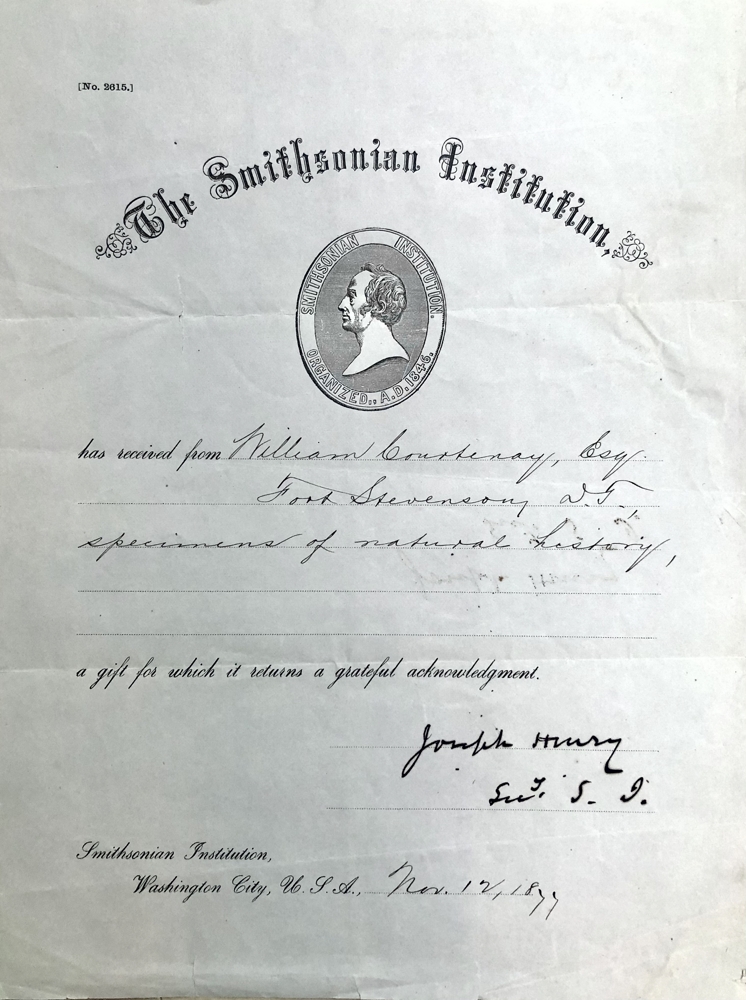

The collection also includes a variety of the Courtenays' personal documents. These include personal writings such as letters, poetry, and essays; handwritten copies of a satirical local newspaper called “The Fort Berthold Banner;” photographs; obituaries; newspaper articles; a receipt of donation from the Smithsonian and an auction brochure for "Indian Curios"; a letter to Courtenay from abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher; naturalization papers, marriage certificates, military records, and other paperwork; and even ephemera such as a lock of hair. It is here that the love story truly unfolds, through letters, Valentines, photographs, and family histories.

William Courtenay was born in London in 1832. At age 30, he moved to the United States, where he settled in upstate New York, then Chicago. He was not a US citizen, but in 1864, he enlisted as a Union soldier and served as a 1st Sergeant in the 13th regiment of the US infantry during the Civil War. After he left the army in 1867, he settled in Montana, first in Fort Benton, where he sold wood along the Missouri River and trading with local Indians. He then spent a year in Fort Buford, Montana, before being appointed as clerk and postmaster at the Fort Berthold Indian Agency along the Missouri River in the Dakota Territory.

In May of 1852, twenty years after Courtenay’s birth, Fannie Patterson was born in New York City. She was the third of six children born to Judge John S. Patterson and Emily A. Patterson. At some point in the 1870s, she turned her sights westward. As a young woman, she packed her things and traveled halfway across the country by herself, finally settling at Fort Berthold. There, she took a job as a schoolteacher, tutoring the local Indians of the Agency in English.[1]

The Fort Berthold reservation was and is home to what are known as the Three Affiliated Tribes: the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes, or, as they were more commonly referred to at the time, the Mandans, Gros Ventres, and Arickarees. Courtenay and Patterson were at Fort Berthold during a time of intertribal conflict as well as conflict between tribal nations and the government. Lean Wolf (sometimes known as Poor Wolf), the second chief of the Gros Ventres, gave a long testimony regarding tensions with the Sioux, transcribed by Courtenay:

"The halfbreeds expressed to the Sioux their dislike of Americans and Promised to join them against the Americans, Should the latter attack the Sioux. Lean Wolf concluded by saying that as far as depredations against the whites was concerned they (the Berthold Indians) had clean hands."

Testimony of Lean Wolf, undated

The earliest surviving record of William Courtenay and Fannie Patterson together is in a receipt roll from August 1879. At the time, Patterson was employed as the only teacher and Courtenay was serving as both clerk and acting agent after Agent Thomas Ellis suffered a stroke and was incapacitated.[2] Only a few months later, in October and November of that same year, Courtenay wrote to Patterson’s father, declaring:

I have had the honor and pleasure of making the acquaintance of your daughter, Miss Fannie; and that acquaintance has ripened into a warmer feeling: in short, I love her passionately and devotedly, and venture to ask you to do me the greatest favor that one man can do to another—to give her to me as my wife.

In a response letter, Judge Patterson expresses surprise at such a short and intense courtship, but he gives his tentative approval, writing of his daughter: "I know just exactly what a devoted, and priceless jewell [sic], as a wife she will be to the husband who will know how to appease her, and will treat her with the kindness she will deserve."

"I feel sure that, if ever a husband loved a wife with devoted and unchanging affection, I shall do so. Her happiness shall be my constant care, and you may rest satisfied that, her future life will be without a cloud, if strong and devoted love can bring sunshine to our home." - Courtenay, letter to J.S. Patterson, November 12, 1879

-

In the summer of 1880, William Courtenay and Fannie Patterson traveled a hundred miles from Fort Berthold to the city of Bismarck. There, on July 19th, the two were wed. William was 47; Fannie was 28. That very same day, Courtenay was officially naturalized as a United States citizen.

When Fannie left for New York to recuperate, Courtenay began to write her long, effusive letters, recording up to a full week in a single letter. He recorded his days from the moment he woke up to the moment he went to sleep. He reported on the state of their garden, the weather, the goings-on of their friends and neighbors, and any other events.

In one instance, he described the lunar eclipse of June 12, 1881 (a well-recorded event which allowed me to figure out the precise date of an undated letter):

I shall never forget the singular beauty of the spectacle; the night was singularly still and calm, not a sound of any kind—not even the hum of a mosquito; I was wishing so much that you were here to watch with me and enjoy the beauty of this rare phenomenon—a total eclipse of a full moon.[3]

Mostly, however, he wrote about how much he loved and missed her: "Although I can’t see you or hear you, yet I feel your presence with me, and I look into my heart and see your photograph; Before I fall asleep I shut my eyes and imagine I see you—the little head with its brown ringlets, the loving blue eyes, the short upper lip, and curving cupid bow mouth, that seems suing for a kiss; How I wish my arms were round you tonight; what a long, loving embrace I would give you! Goodnight, my own dearest darling, my heart is full of love for you."

Unfortunately, no letters from Fannie to William survive. What did survive, however, are letters written to Fannie from her students Wolf Chief and Eagle while she was ill.

"My teacher going away I am Sorry my teacher Mrs Wm Courtenay away I do not like" -Wolf Chief, undated

Wolf Chief of the Gros Ventres began by writing to his teacher, Mrs. Courtenay, but after the Courtenays moved off the reservation and to Miles City, he began to address his letters to Mr. Courtenay instead. These letters complain of current conditions on the reservation and ask for Courtenay’s help, often asking him to appeal directly to the “Great Father”—that is, the President of the United States.

"Friend William Courtenay," he wrote, in the rudimentary English taught to him by Fannie Courtenay. "Please, you own sugar coffee calico flour, I want to keep store up here. your Ways let me know. I want to know. Write soon. as you know. the agent does not like me. and.... pays us no money. We are poor. We do not want shows."

Courtenay was one of many white government official contacts that Wolf Chief appealed to in an attempt to flag the attention of the Indian Office and have his tribe's problems addressed. Though it was almost certainly without any action on Courtenay’s part, Wolf Chief was eventually able to open his own store. This allowed for competition against the licensed trader who had previously held a monopoly, and helped pave the way for the inclusion of literate Indians as agency employees rather than solely white employees.[5]

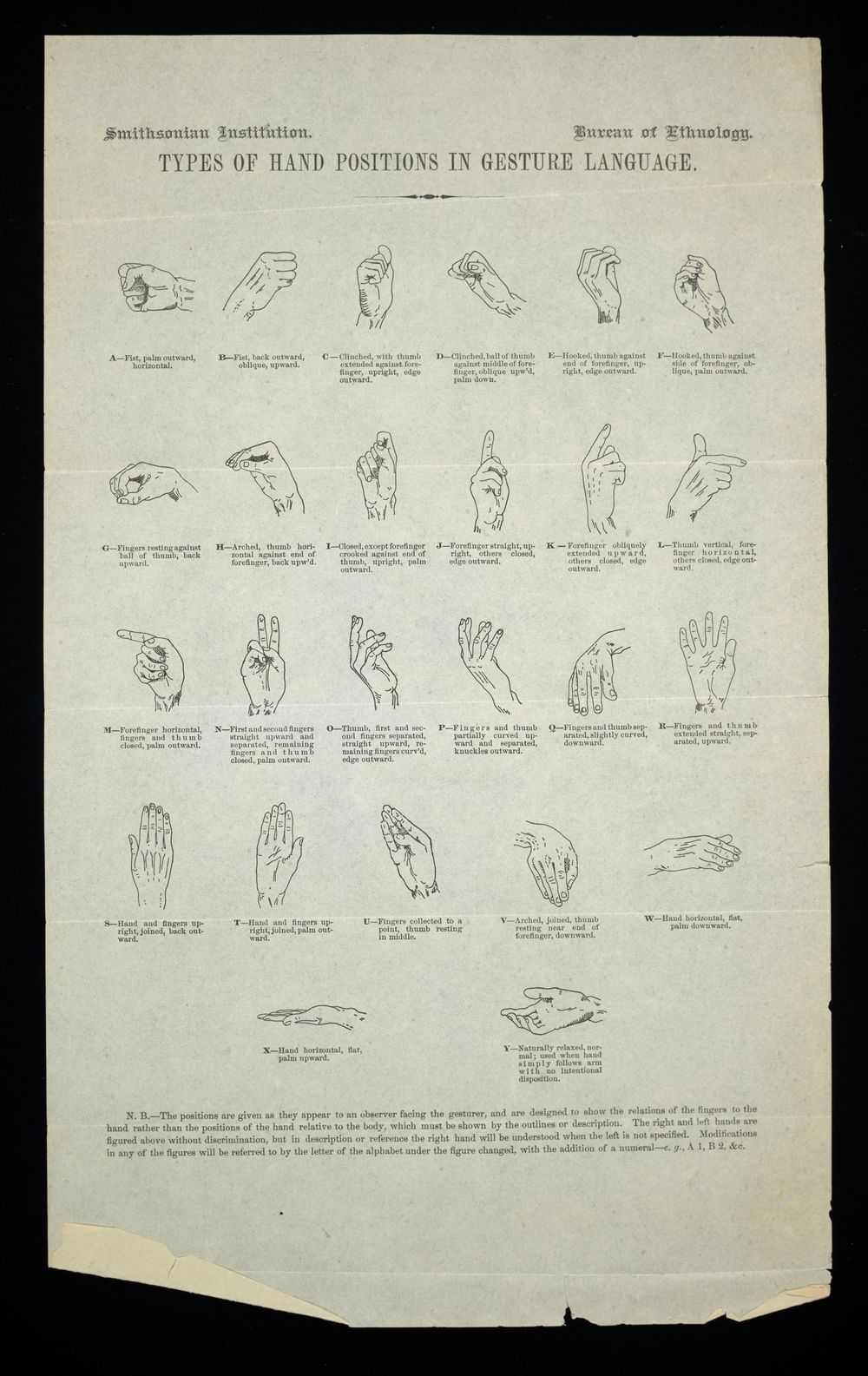

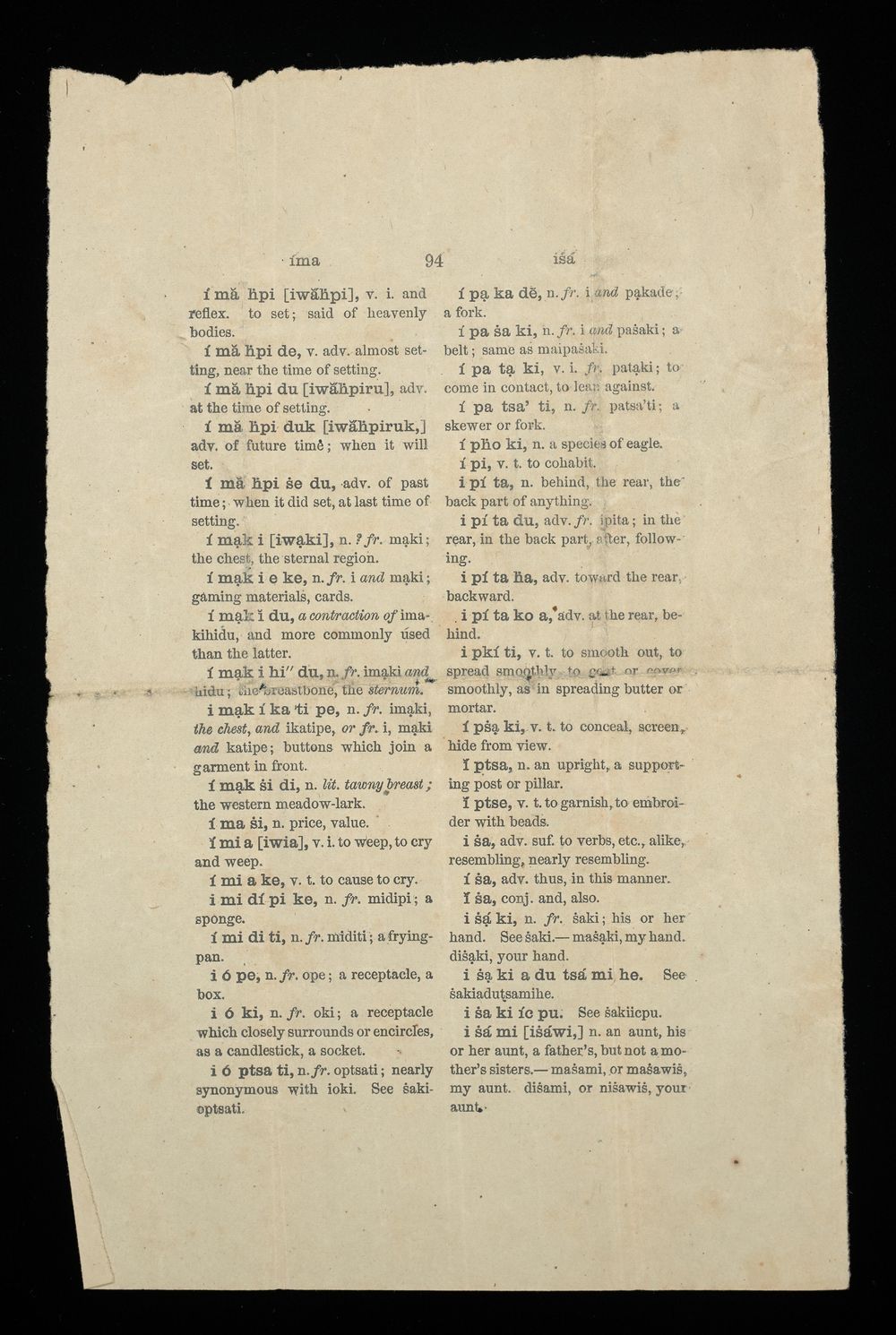

In addition to writings by Fannie Courtenay's English students, the collection also includes two pages of dictionaries from local languages. One is an excerpt from ethnologist Garrick Mallery's 1881 report to the Bureau of Ethnology on indigenous sign language, and the other is a page from a Hidatsa dictionary compiled by Washington Matthews in 1873 (of which Firestone has a full copy).[6]

Despite these samples of tribal languages, Courtenay was reportedly against the use of vernacular languages being used in teaching. In The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri, Roy W. Meyer quotes Courtenay as saying, “it is wholly unnecessary for a teacher of Indian children to acquire their language and only defeats the object contemplated of imparting a knowledge of English.” In general, Meyer characterizes Courtenay as very pro-acculturation and in support of the government breaking up tribal organizations and traditions.[7]

“A painter fell off a scaffold with a pot of paint in each hand. He was taken up insensible, but as soon as he was restored to consciousness, he murmured ‘I went down with flying colors anyhow.’”

- Fort Berthold Banner, February 10, 1879

The letters to Fannie are not the only items in the collection that provide a window into life at the agency. Courtenay's personal papers include three copies of a satirical newspaper, written in Courtenay's handwriting. These papers, dated from February and March, 1879, contain local "news," mostly in the form of puns or light jabs at other members of the agency. Topics such as “Gossip from the Quilting Bee,” “Irish Wit,” and “How to be happy though married” (written long before Courtenay was actually married) provided—albeit likely mostly fictitious—glimpses of daily life. The Fort Berthold Banner is remarkable for its sheer uniqueness—research across digitized archives yielded nothing resembling a manuscript satirical "newspaper" from a nineteenth-century Indian reservation. It's unclear how the Banner might have been distributed, and it would be difficult now to identify its readership. But its hand-written nature suggests it was shared among a small circle at the reservation, perhaps even handed out anonymously amongst Berthold employees. Although anything written in these issues must be taken with several heaping tablespoons of salt, it brings further insight to the vibrant, human relationships among the agency employees and their families in Fort Berthold.

"Indian Curiosities... Comprising dancing ornaments, awl cases, war stones, coup sticks, wooden bowls, war bonnets, dancing gaiters, head dresses, beaded sacks, mink and bear skins, buffalo ornaments, mocassins[sic], shields, war clubs, tomahawks, spears, knives, &c &c &c. Many Exceedingly Rare and Curious, and which cannot be duplicated... THE WHOLE TO BE SOLD AT AUCTION."

- Auction Catalog of Courtenay's Collection of "Indian Curiosities"

At one point in his letters, when discussing finances, Courtenay wrote: "I'll get rid of the Ind'n curiosities as soon as ever I can, and won't then be cramped for money, you see there are about $700 locked up in them." Sure enough, in October 1881, Courtenay put 450 items obtained from the Three Affiliated Tribes up for auction. This turned a profit of $416.38—well under $700, if this was the whole collection he spoke of, but still a good amount of money to put into savings.

In addition to the auction, Courtenay personally donated "specimens of natural history" to the Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology, and he purchased hundreds of dollars' worth of artifacts from the Fort Berthold tribes on behalf of General William B. Hazen, who was stationed at nearby Fort Buford. Upon Hazen's death, his widow donated a collection of over 170 artifacts to the Smithsonian.[8]

In 1882, Courtenay took a job in commercial livestock trading, real estate, and insurance. Both of the Courtenays left for Miles City, Montana, leaving Fort Berthold behind them. There, they raised four daughters. Fannie and William remained by each other's sides until William died in 1901. Fannie followed him in death seven years later, passing away in July 1908.[9]

Pieces of this collection fit into the wider narrative of intertribal and governmental conflicts, the sale of Indian artifacts, and the politics of the Indian Office in US history more broadly. The beating heart at the center of the collection, however, is something very human. At its core, these papers tell the story of ordinary people, who lived and loved in the nineteenth-century West.

Look on the bright side of things little sweetheart, and get all the happiness possible. Believe there is one who prizes you as the apple of his eye, whose very life is bound up with you and whose heart is filled with love for you. I would not exchange my darling little wife for any wife in America. Good bye, and a big kiss O for another week. May God bless and keep you my own dear, dear little wife.

A full transcript of the surviving letters from Courtenay to his wife, Fannie, can be viewed here.

[1] Census of the state of New York, for 1855. Microfilm. Various County Clerk Offices, New York. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/1654118951:7181; 1870 U.S. census, population schedules. NARA microfilm publication M593, 1,761 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/33361039:7163.

[2] Roy W. Meyer, The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri: The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras (Lincoln, London: University of Nebraska Press, 1977), 117.

[3] "Total Eclipse of the Moon: 1881 June 12." HM Nautical Almanac Office, UK Hydrographic Office, 2006-2018. http://astro.ukho.gov.uk/eclipse/1211881/

[4] Image from North Dakota Studies -- State Historical Society of North Dakota. "Section 3: Rations and Annuities." https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-iii-waves-development-1861-1920/lesson-2-making-living/topic-8-working-reservation/section-3-rations-annuities

[5] Meyer, 157, 154.

[6] The sign language dictionary pages are excerpted from Garrick Mallery, "Sign Language Among North American Indians Compared with that Among Other Peoples and Deaf-mutes," in First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1879-1880, (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology, 1881), 263–552.

[7] Meyer, 128, 295 n. 70.

[8] Candace S. Greene (2020) The Hazen collection: A new source on Arikara material culture, Plains Anthropologist, 65:256, 357-377, DOI: 10.1080/00320447.2020.1786621

[9] United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/76543273:7602; State of Montana, Montana State Deaths, 1868-2018, State of Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, Office of Vital Statistics, Helena, Montana. https://search.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=5437&h=732369&indiv=try&o_vc=Record:OtherRecord&rhSource=60525