Interracial Marriage and Famous Familial Relations: Real Photo Postcards and the Tourism Economy in San Francisco’s Chinatown

By: Lois Wu '23

Access the digitized collection of real photo postcards via Princeton University Library.

I’m happy in my home. My life with my husband has been perfect, for he, like other Chinese husbands, is gentle, considerate and an excellent provider. Surely my lot is happier than that of a so-called American wife, who never knows her marital status and doesn’t know what real happiness can be.[1]

Between 1906 and 1916, dozens of articles about the marriage of Ella May Clemmons, a white woman, and Wong Sun Yue, a Chinese immigrant, peppered newspapers across the country, from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Boston, Massachusetts to Emporia, Kansas and Jonesboro, Arkansas.[2] Ella May, born in Montezuma, Illinois in the late 1850s, had been living and working in San Francisco’s Chinatown since the late 1890s.[3] She was running a kindergarten school for Chinese children and a Catholic missionary in the neighborhood when the earthquake and fire struck in 1906.[4] She helped with cleanup efforts, which is how she met Wong Sun Yue, a Chinese merchant who had immigrated to America in 1894.[5] White-Chinese interracial marriage was illegal in California at the time, following the amendment of anti-miscegenation laws in California in 1880.[6] The two ran a curio store and tea shop in Chinatown following the earthquake.

If Ella May’s story of working in Chinatown and marrying a Chinese merchant as a white woman in the early 1900s wasn’t interesting enough, she was also the sister of a famous divorcee. Katherine Clemmons, Ella May’s younger sister, had a brief acting career early in life and was married to Howard Gould, son of financier Jay Gould, from 1898 and 1909.[7] The two had a messy divorce, well publicized by the papers. Ella May was sometimes dragged into these matters, with newspaper reports detailing the extents to which Howard went to try to get Ella May to testify against her sister in court.[8] Between Ella May’s illegal interracial marriage and Katherine’s famous ex-husband, the press had no shortage of events to report on. All eyes were on the Clemmons-Gould-Wong family in the papers.

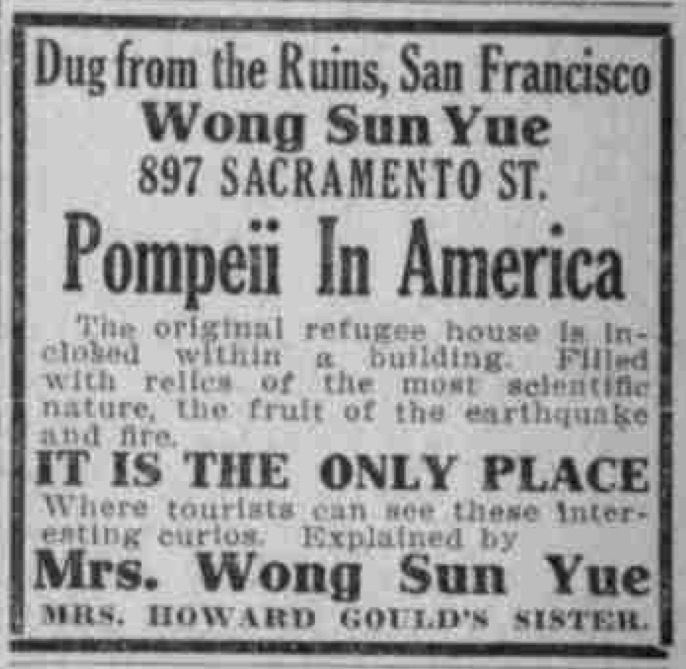

Ella May capitalized on the national notoriety she gained through her interracial marriage and her sister’s contentious divorce to attract people to the curio store and tea shop she and her husband ran in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Called “Relics Dug from the Ruins,” the Wong Sun Yue Clemenses appealed to tourists visiting Chinatown by selling, well, relics dug from the ruins of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, as well as real photo postcards of herself and her husband for 15 cents apiece, and cures for opium addiction.[9] The Wong Sun Yue Clemens’ store fits into the spirit of rebuilding that animated Chinatown in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake.

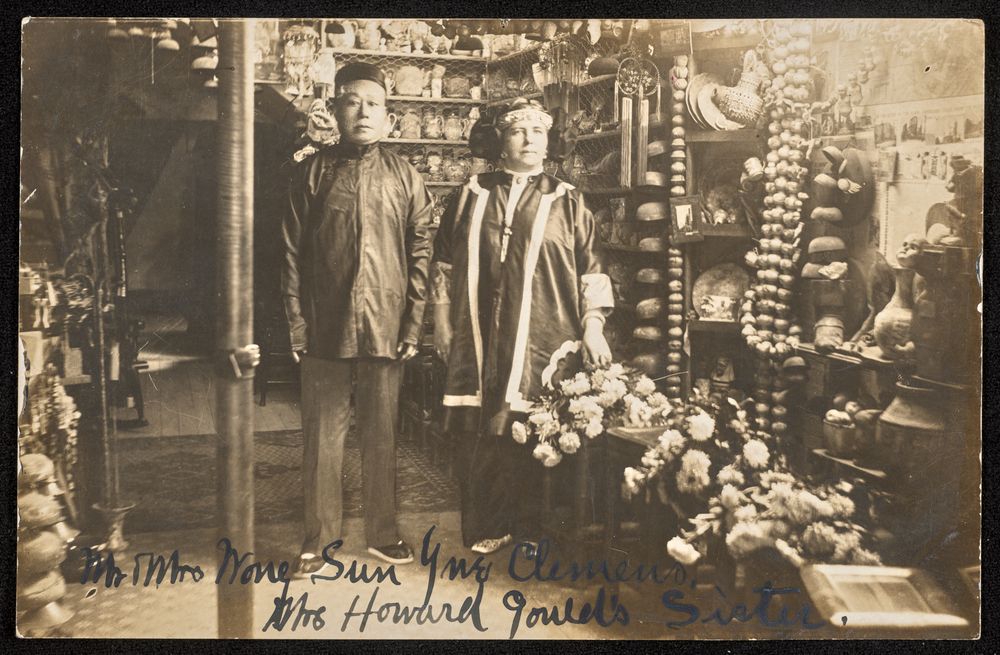

According to one account, at least 100 different real photo postcards sold by Ella May and Sun Yue’s store survive today, many in multiple copies.[10] The Princeton University Library owns nine different postcards sold by the couple and five duplicate copies, for a total of 14 postcards in the collection. Though not all of the postcards sold by the couple feature a picture of the couple, all of the 14 in this collection do. Each postcard is about 3-3/8” by 5-3/8” large.

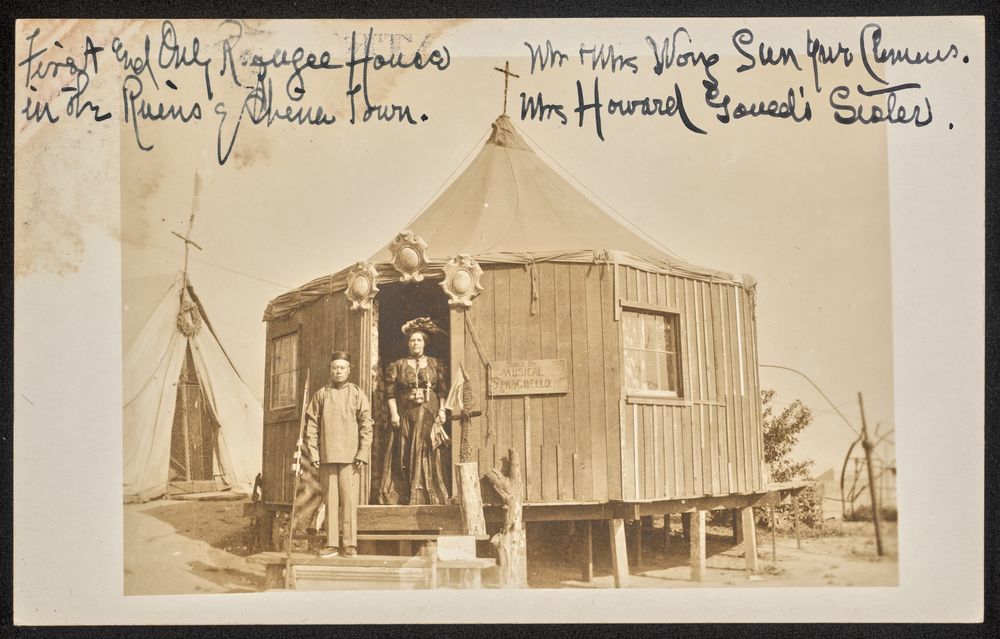

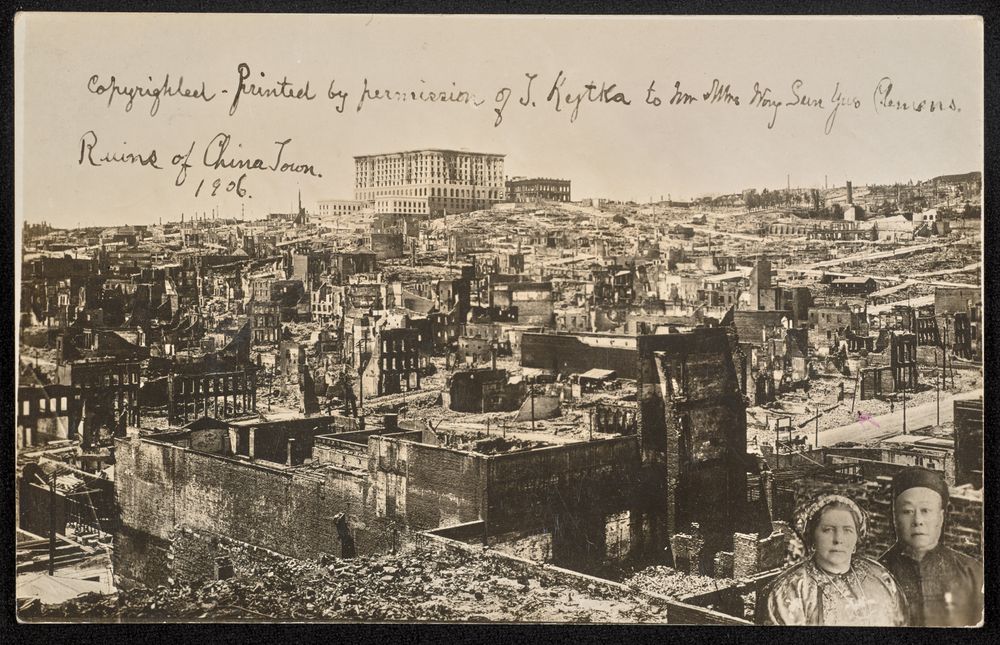

Of the nine unique postcards, six are of the couple in their store. Wall shelves lined to the ceiling with various goods surround them. Of the other three postcard images not taken within the store, one was taken in front of a refugee house used in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake. The couple later reconstructed the refugee house inside their store.[11] A second is a photograph looking out over Chinatown after the 1906 earthquake and features the couple pasted into the bottom righthand corner, from another image, like a collage. The third is of the couple standing next to each other on what appears to be a rooftop with vegetation growing in the background.

In all of these, the couple are dressed in traditional Chinese attire of the time, always wearing laceless shoes and often a tang suit or magua, two styles of Chinese jackets.[12] Ella May appears in a Western style dress only in the postcard made in front of the refugee house.

All of the postcards have handwritten words on the front. Nine say: “Mr + Mrs Wong Sun Yue Clemens, Mrs Howard Gould’s Sister.” Of the five others, one lists the name of the couple as “Mr + Mrs Wong Sun Yue,” without “Clemens,” and again mentions Ella May’s sister. Two others list the name of the couple as Wong Sun Yue Clemens, but this time with the address of the first location of their store—897 Sacramento Street. The last two, which are duplicates of the same postcard design, say: “Copyrighted – Printed by permission of T. Kytka to Mr + Mrs Wong Sun Yue Clemens, Ruins of China Town 1906.”

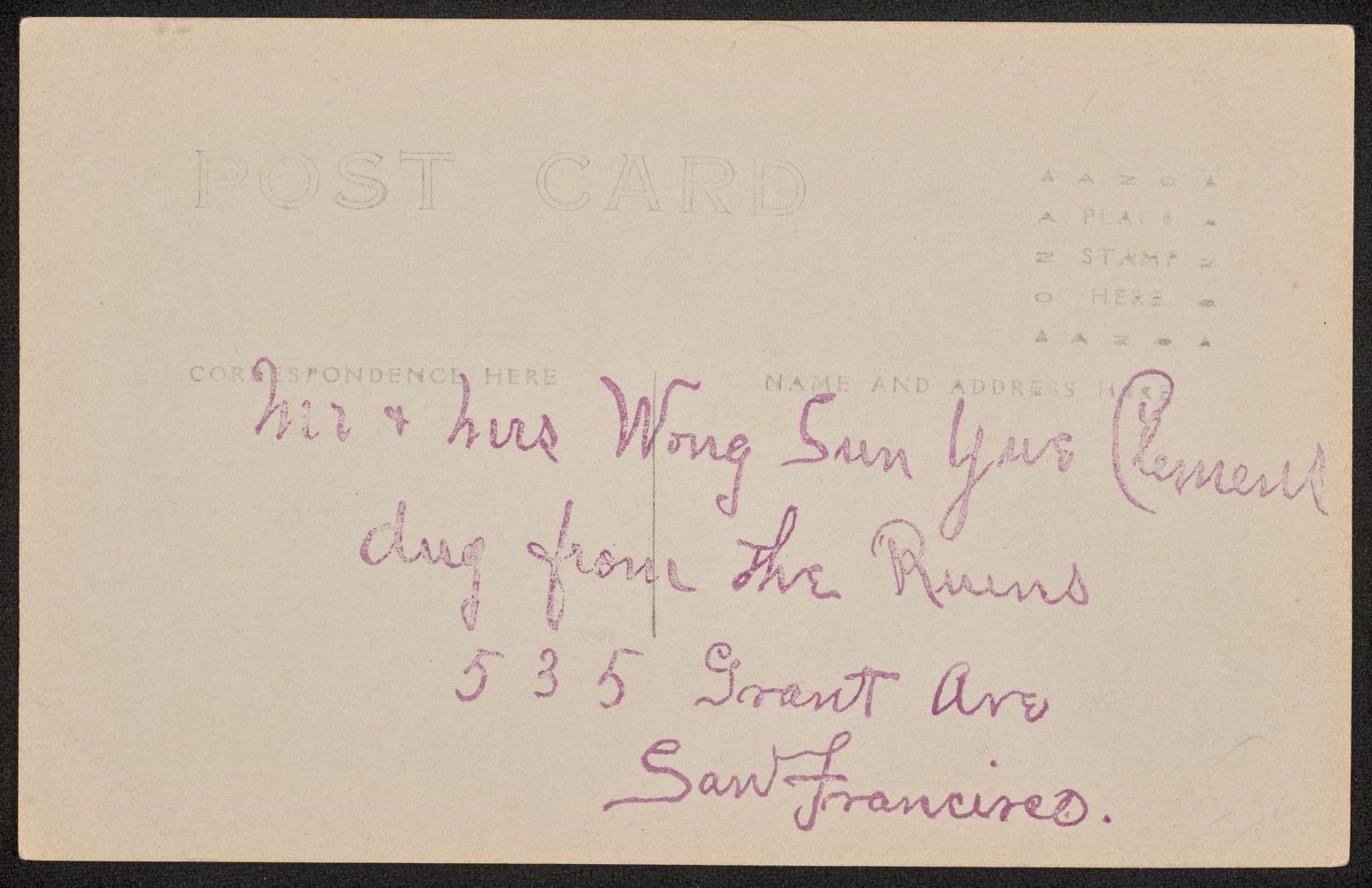

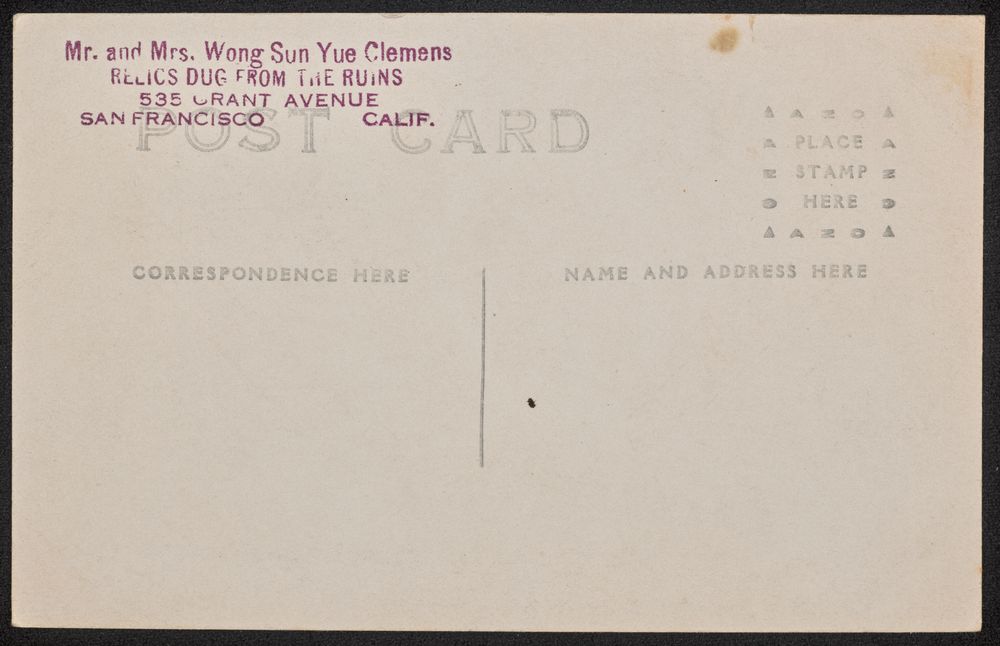

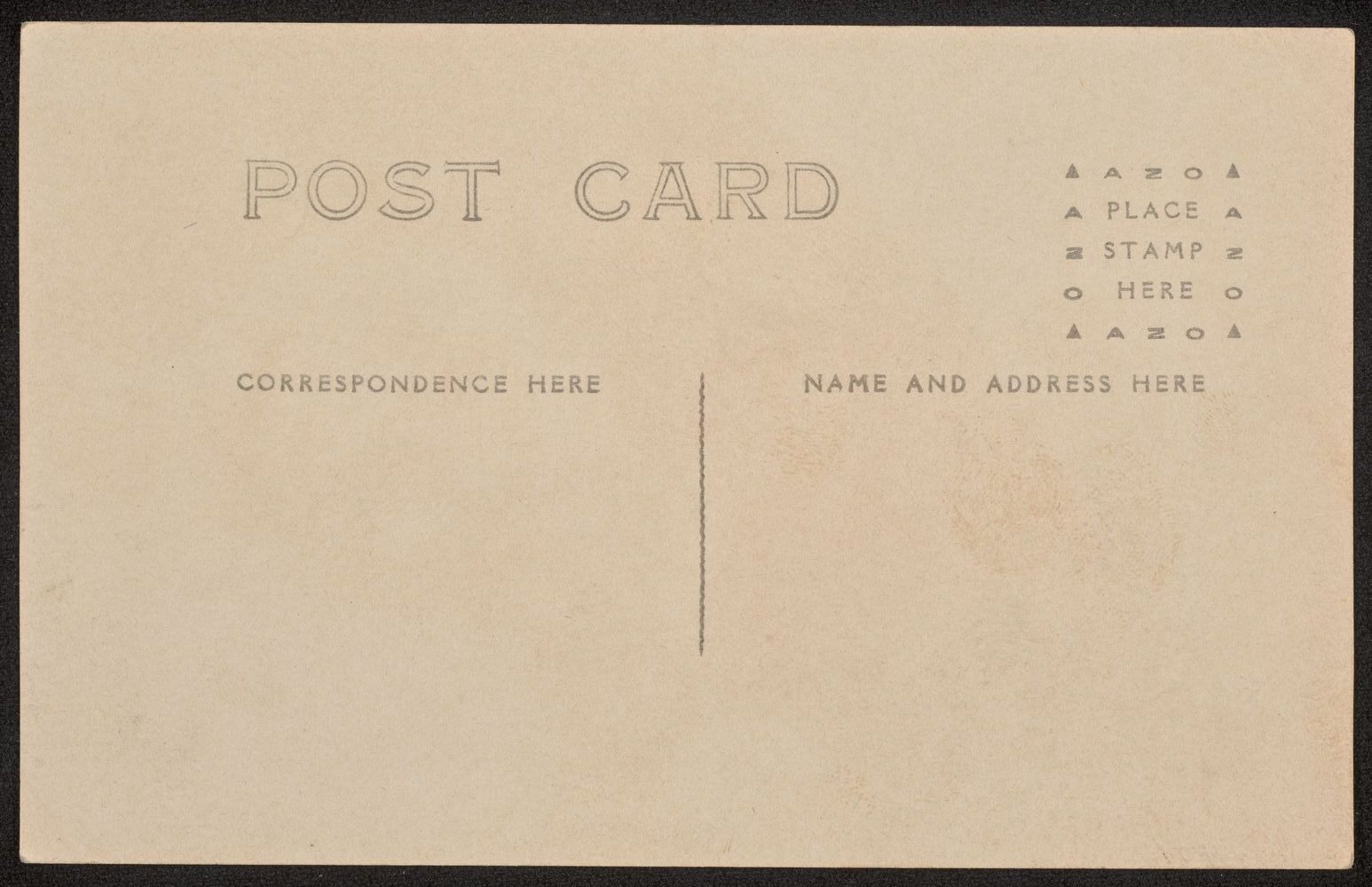

On the backs of the postcards, eleven have been branded with the couple’s name, the name of the store, and the second location of the store, all by rubber stamps. Nine of these postcards were stamped by the same stamp, with a design approximately 2” by ½” large. Two others have identical stamp designs, though they differ in the size of the stamp. One stretches almost across the entire width of the long side of the postcard, while the other stretches across the short side. Besides stamps, two postcards have handwriting on the back, describing what the tourists who owned the postcards saw on that day. The other three backs are empty. None of the 14 postcards appear to have been mailed, as they do not bear postage stamps, though they could have been placed in envelopes and mailed in that way. Six bear penciled prices and other letters on the back, perhaps from different sellers.

All the postcards are in good condition, with some minor evidence of age in their worn corners and edges, but otherwise untarnished. One postcard—the one in front of the refugee house—has some discoloration in the upper left-hand corner.

So, who were Ella May Clemmons and Wong Sun Yue?[13] Ella May Clemmons was born in Montezuma, Illinois in 1859 or 1860.[14] Her parents divorced at a young age and her mother ended up remarrying and moving to Palo Alto around the early 1880s. Ella May and Katherine moved with her. Katherine gained attention for her acting in the ‘80s and Ella May traveled with her on her first world tour, but ended up returning to California in the late 1890s.[15] The kindergarten school for Chinese children she ran was called “Little House of Gold” and the missionary “Christ Angel.”[16] She met Wong Sun Yue in the cleanup efforts in the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire.

Accounts of the story begin to vary after Ella May and Wong Sun Yue meet. The San Francisco Chronicle ran two stories in 1934 and 1936 telling a more complete story about the couple’s life, but these and other stories in the papers from earlier years about the couple seem to rely on Ella May as their main source. I searched for written records left by Wong Sun Yue, but came up empty. The 1910 Census describes Wong Sun Yue as a retail merchant who was born in China in 1856 and spoke English as his native tongue, which could not have been true.[17] Ella May’s age is listed incorrectly in the entry below Wong Sun Yue’s (see footnote 14), so this census record may not be the most trustworthy.

Regardless, the story appears to be that sometime after the two met, they began living together. Some accounts report that Ella May fell in love with Wong Sun Yue, but knew from the beginning that she could not marry him, as he already had a wife in China.[18] Others agree that the two were never married, not because of Wong Sun Yue’s other wife, but because Ella May saw him as someone who needed to be saved from an opium addiction, not as a love interest.[19] In still others, Ella May is said to have stated that she and Wong Sun Yue were married “in accordance with the Chinese teachings.”[20]

Ella May and Wong Sun Yue could not have been legally married in California, so an unofficial cohabitation situation that they called marriage in name is likely. In 1880, the state of California made it illegal for any white man or woman to marry a “Mongolian,” a term used to refer to people of East Asian descent. At the time, people of East Asian descent in California would mainly have been Chinese and Japanese immigrants.[21] Beyond state laws, the federal Expatriation Act of 1907 established that an American woman who married a non-citizen immigrant would lose her own American citizenship.[22] White-Chinese interracial marriage was illegal and highly discouraged by state and federal laws.

All persons about to be joined in marriage must first obtain a license therefor [sic] from the County Clerk of the county in which the marriage is to be celebrated… the Clerk shall not issue a license authorizing the marriage of a white person with a negro, mulatto, or Mongolian.[23]

One article that was published in two different newspapers does mention that Ella May “voluntarily relinquished her rights as a native-born Californian yesterday to become as much as possible an all-around Chinese, like her husband.”[24] This seems to indicate that the two were somehow married and that Ella May lost her citizenship as a result of the marriage. However, both are short articles and do not go into details about how this occurred or what the legal process was like. This renouncement of citizenship is not mentioned anywhere else.

Wong Sun Yue eventually left Ella May while the two were in China to set up a school for children, after sailing from California in 1915. Ella May returned to America alone and issues with citizenship or her lack thereof are never mentioned. Two options are possible here: Ella May either never completely renounced her citizenship and only did so in name, or she did officially renounce her citizenship but her connections with her sister and her sister’s money allowed her to still navigate America later in life, after her separation with Wong Sun Yue, with ease. Regardless of her citizenship status, it seems highly unlikely that Ella May and Wong Sun Yue were ever legally married, though I will continue to refer to them as a married couple, as that is how Ella May spoke of her and Wong Sun Yue in newspapers.

The couple owned a curio store and tearoom together, first located at 897 Sacramento Street, then 535 Grant Avenue. These postcards, with their visible advertisement of the location and exploitation of attention-seeking imagery of a “married” white woman and Chinese man, were used as advertisements of the store.[25] The visible “Mr + Mrs Wong Sun Yue Clemens” writing on the front of each postcard confirmed to the viewer that the two people pictured on the postcard were, in fact, an interracial couple.

This name for the couple combines the Chinese naming conventions of listing one’s surname first, Wong, and a married woman retaining her maiden name after marriage, which Ella May somewhat did by putting her last name at the end of the Wong Sun Yue.[26] It would be difficult to say how much of this was because Ella May wanted to follow Chinese naming conventions, but the name did draw attention in combining both a white surname and Chinese full name. Moreover, Ella May misrepresented her own last name, writing “Clemens” instead of the correct “Clemmons.” She falsely claimed to be the niece of Mark Twain, whose birth name was Samuel Clemens.[27] Adding on the third advertising tactic of writing “Mrs Howard Gould’s Sister” to gain the attention of those interested in the gossip of the day, Ella May appears to have been a shrewd businesswoman.

Postcards were extremely popular throughout the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The craze began at the Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893, where postcards were a popularly purchased souvenir.[28] At the time, government-issued postcards required one-cent stamps, while postcards produced by private companies required the typical two-cent stamp used on letters. In 1898, Congress authorized private companies to produce “private mailing cards” that also required one-cent stamps, which truly set off the postcard boom.[29] By 1913, the number of postcards sent individually across the country equaled ten times the population. A total of almost one billion postcards was sent in 1913.[30] The fact that none of the fourteen Wong Sun Yue Clemens postcards were sent is not unusual; by one estimate, more than half of postcards purchased were not mailed. Instead, they were saved, traded, or shared in-person with friends and family.[31]

The last important date in this timeline of postcard popularity history is 1907. In 1907, postcards were allowed to have space on the back for both a message and the address, divided by a line in the middle. Before this, only the address was allowed on the back of the postcard. Postcard manufacturers often left black space on the side or bottom of a postcard for a message to be written, but people sometimes wrote over parts of the image too, when sending an especially long message.[32] The writing on the front of the Wong Sun Yue Clemens postcards, likely done by Ella May, served as a sort of caption for the photograph and an advertising technique, but this general format of writing over photographs in dark ink was not unusual for the time. All of the fourteen postcards also have space for both a message and the address on the back, so all postdate March 1, 1907, the day when the new regulation came into effect.[33]

These postcards are all “real photo postcards,” meaning they are actual photographs printed on light-sensitive photographic paper with postcard backs.[34] Real photo postcards stand in opposition to printed postcards which were not made directly from negatives and instead required first making a printing plate or screen of a photograph, which were then used to print subsequent postcards. The first step of creating the plate or screen was expensive. Typically, once a plate or screen was made, thousands of cards would be made from the prototype. Because of this, small businesses that wanted to advertise through postcards, like the Wong Sun Yue Clemens’ store, would hire commercial photographers to create real photo postcards as advertisements.[35]

The first real photo postcard-stock paper produced by a commercial manufacturer is believed to have come about in 1899. This first manufacturer was a brand called Velox. Prior to this, photographers had created individual photo postcard-stock paper by coating normal postcards in light-sensitive solution. Other manufacturers soon began producing their own photo postcard-stock paper, starting in 1902. By analyzing the designs on the backs of each postcard, which are unique to each brand, I estimate that eleven of the postcards are Azo brand and the paper was manufactured between late 1907 and mid 1909.[36] The remaining three Kruxo postcards were printed on paper produced between late 1907 and mid 1908.[37]

I was not able to ascertain who might have taken and created these real photo postcards. I tried searching the San Francisco Examiner for “postcard photographer” or “post card photographer,” hoping to find an advertisement one might have put in the paper. I had three results—two were “help wanted” advertisements looking for a postcard photographer and the third was an ad for a rental property, pitching the property as suitable for a postcard photographer.[38] Based on these results, there seems to have been a market for postcard photographers, but I was not able to find any specific names.

The one photographer who is credited in these postcards is “T. Kytka.” He is the source of the photograph of the 1906 ruins of Chinatown where Ella May and Wong Sun Yue are pasted in at the bottom—a technique not unfamiliar to postcards at the time. In both printed and photo postcards, montages of multiple photographs or photographs edited together with other photographs to give the impression of being just one photograph were commonly created.[39] This was especially the case if the resulting postcard would look more appealing to buyers.[40]

T. Kytka was likely Theodore Kytka, a handwriting expert, photographer, and criminal investigator who worked for the San Francisco Police Department in the early 20th century.[41] All of the secondary sources writing about these postcards list the photographer as J. Kytka or John Kytka. However, the handwriting on the postcard looks like a cursive T, particularly when compared to the cursive F on one of the postcards with “897 Sacramento St. S.F.” written on the front and the cursive T on the postcard with “First and Only Refugee House in the Ruins of China Town.” Cursive letter T’s and F’s are typically identical, save a horizontal line drawn through the F.

The couple’s store seems to have been successful. I found advertisements for their store when it was located at 897 Sacramento from August 2, 9, and 23, September 6 and 13, and October 4 and 18, 1909 in The San Francisco Examiner, but no advertisements for the Grant Avenue location.[42] In this ad, Ella May is mentioned as someone who will explain the curios and items in her store. Ella May wanted to help spread a positive image of Chinatown to tourists, many of whom were visiting from New York.[43] She is repeatedly mentioned in newspaper articles as working against the images of “morbid” Chinatown that typical tourist guides spread.[44] She leant into how “different” her marriage and life in Chinatown was to gain customers, but wanted to spread a different image of Chinatown with a positive valence, not a different image with a negative valence.

Mrs. Wong Sun Yue, formerly Miss Clemmons, and a sister of Mrs. Howard Gould, cherishes the ambition of making the Celestials better known and appreciated by the American people… She declares that guides show only the morbid side of Chinatown, while there is in reality an immense amount of progress going on there.[45]

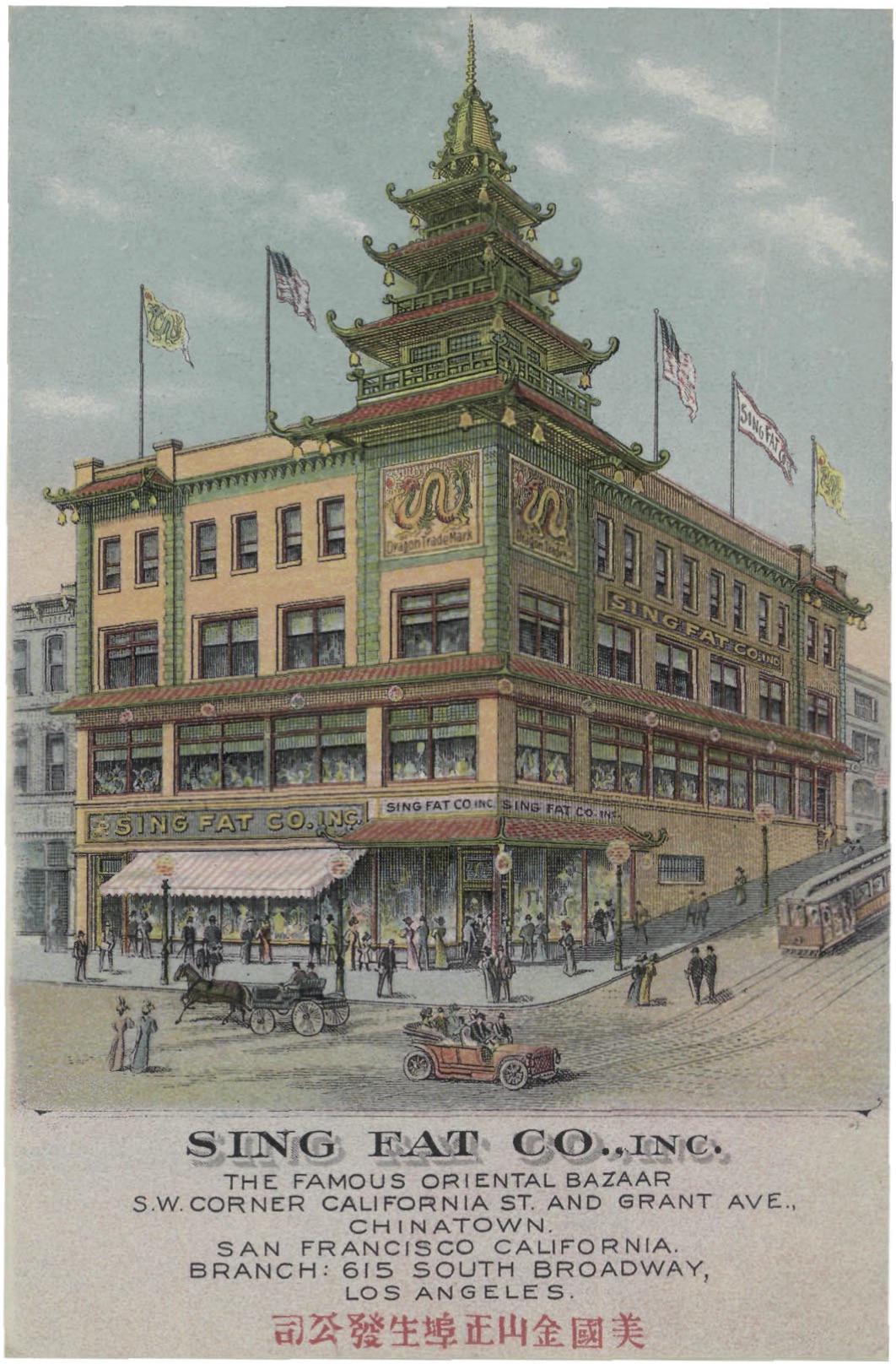

The success of the store, in part, may have been because of the popularity of Grant Avenue as a tourist destination. Much of San Francisco’s Chinatown was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and subsequent fire. During this rebuilding, the community, led by Chinese businessmen whose businesses were located on Grant Avenue, intentionally hired architects who designed structures that looked distinctively “Chinese.” They wanted to make Chinatown a tourist attraction rather as an ethnic enclave that was mysterious and unnecessarily occupied prime real estate in the city.[46] Prior to the earthquake, buildings in Chinatown looked just like any other buildings in San Francisco, architecturally. What set the buildings apart, visually, were storefront decorations, not built-in structural differences.[47]

These efforts worked. This success can be seen in the description of Grant Avenue in guidebooks of San Francisco published in 1910 and 1915. One guidebook of San Francisco published in 1915 describes the post-earthquake street as follows:

At the corner of California Street and Grant Avenue is the great Sing Fat store, one of the most famous Oriental bazaars in the world, as much a rendezvous for sightseers as for purchasers. Everyone is welcome. Then there are the Sing Chong stores, the Canton Bazaar, the Nanking Bazaar of the Fook Who Company, the Wing Sing Loong Bazaar, and others stretching along Grant Avenue for two blocks, each a veritable museum of Chinese art.[48]

The location of the Wong Sun Yue Clemens’ store, at 535 Grant Avenue, was half a block away from the Sing Fat Co. and Sing Chong Bazaars. These two bazaars were located on adjacent corners of the intersection of California Street and Grant Avenue. They were two of the first buildings to be rebuilt, with pagoda-inspired structures on their roofs and colorful tiling. Passages in this and other guidebooks describe “balconies, balustrades, and pagoda-like roofs [that] preserve the striking features of Chinese architecture”[49] in Chinatown and “carved timbers and tiled roofs of China… brilliant in green and red and gilding”[50] of the area.

I was unable to ascertain what 535 Grant Avenue looked when the Wong Sun Yue Clemenses ran their store out of the location. 535 Grant Avenue today is a jewelry store that bears no significant architectural distinctiveness. It is difficult to say how much the Wong Sun Yue Clemenses contributed to the spirit of rebuilding Chinatown to aesthetically look like a tourist destination in terms of their own building. However, they definitely fed into the general spirit of otherness in their magnification of the oddity of their interracial marriage, Ella May’s connections to an extremely wealthy man and his messy divorce, and their selling of “Relics from their Ruins.” Ella May saw herself as wanting to contribute to rebuilding a positive view of the oddity of Chinatown.

I want to show my American women friends the real beauties of Chinatown—to undo all that has been said about the Chinese ‘underworld’ here by pointing out the crowning glories of their ‘upper world.’ In showing American women the highest pinnacles of Chinese attainment, glorifying the accomplishments of these people and pointing out their sterling qualities I hope to realize a dream of many years and to render a lasting service to the Chinese people.[51]

Despite how happy Ella May seemed in her interracial marriage in the first decade of the 20th century, the couple’s story does not have a happy ending. In 1915, they moved to China, with the intention of setting up a Montessori school for children. They were financed by Katherine. While in China, however, Wong Sun Yue told Ella May he wanted to return to his Chinese wife and left Ella May for good. He is said to not have had any plans to ever return to America. Ella May returned to San Francisco soon after. She passed away in September 1935, at the hands of a self-proclaimed “doctor,” who isolated her, did not improve her health, and later married her nine days before she passed.[52] He inherited the money Ella May received from Katherine’s will when she passed in 1930, a sum of around $80,000.[53]

The story of the Wong Sun Yue Clemenses lives on in the many photo postcards that still circulate today.

[1] “Chinese Husband Better than Gould Says Sister-in-Law,” The Denver Post (Denver, CO), June 28, 1909.

[2] “Takes up Dragon; Renounces the U.S.,” The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), June 16, 1907; “Woman Turns Chinese,” The Sunday Herald (Boston, MA), June 16, 1907; “Will Become Chinese,” The Emporia Gazette (Emporia, Kansas), June 18, 1907; United Press, “Mrs. K. C. Gould to Fight for Estate,” Jonesboro Weekly Sun (Jonesboro, AK), October 7, 1914

[3] Ancestry.com, U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012;

[4] Neil Hitt, “Ella Clemmons Tells Why She Spurned Riches, Wed Chinese,” The San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), November 26, 1934; Neil Hitt, “Mystery in Death: Chinatown ‘Christ Angel’ Puzzle,” The San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 18, 1936

[5] Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006.

[6] Deenesh Sohoni, “Unsuitable Suitors: Anti-Miscegenation Laws, Naturalization Laws, and the Construction of Asian Identities,” Law & Society Review 41, no. 3 (September 2007): 587-618.

[7] Ella Tanzer, “Biographical Sketch of Katherine Clemmons Gould,” Alexander Street, accessed April 18, 2022, https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1009054719.

[8] “Asks Chief to Protect,” The Sunday Oregonian (Portland, OR), October 20, 1907.

[9] “Sister of Howard Gould’s Wife Now Chinatown Queen,” Fort Worth Telegram (Fort Worth, TX), July 19, 1908.

[10] Kathryn Ayres, “Relics Dug from the Ruins,” San Francisco Bay Area Post Card Club, August 2008, http://www.postcard.org/sfbapcc2008-08-s.pdf.

[11] “Pompeii in America,” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, CA), August 2, 1909.

[12] Ling, “Tang Suit – Chinese Traditional Costume (History & Change),” Newhanfu, April 1, 2021, https://www.newhanfu.com/14182.html.

[13] A number of sources—both primary and secondary—already tell the story of Ella May’s life and her tearoom and curio shop, so I have focused more on the photo postcards as objects in this paper. These sources include a college student’s senior thesis, a postcard club newsletter, a biography on Find a Grave, and newspaper articles during and after Ella May’s life; Hitt, “Ella Clemmons Tells Why She Spurned Riches”; Hitt, “Mystery in Death”; Ayres; Patrick Lozada, “Taking Up the Dragon: A Case Study of Chinese-White Intermarriage in the Early 20th Century,” Bryn Mawr, April 22, 2011, https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/bitstream/handle/10066/6742/2011LozadaE.pdf?sequence=2; Linda Guynup Dewey, “Ella May Clemmons,” Find a Grave, April 16, 2013, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/108621688/ella-may-clemmons.

[14] In the 1910 Census records, Ella May is listed as being 44 years of age in 1910, which would put her birth year in 1866 or 1865, but this must be inaccurate. She is repeatedly described as Katherine Clemmons’ older sister. Katherine’s tombstone lists November 17, 1861 as her birthdate, so Ella May must have been born prior to that. I estimate 1859 or 1860 because her parents, Seldon P. Clemmons and Martha J. Killpatrick, married in 1859; Ancestry.com, U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012; Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006; Ancestry.com, Illinois, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1800-1940 [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016.

[15] Hitt, “Ella Clemmons Tells Why She Spurned Riches.”

[16] Hitt, “Mystery in Death”; Hitt, “Ella Clemmons Tells Why She Spurned Riches.”

[17] Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006.

[18] Hitt, “Mystery in Death.”

[19] Hitt, “Ella Clemmons Tells Why She Spurned Riches.”

[20] “Oriental Romance of Actress Ends Shrouded in Mystery,” Carson Citizen (Tucson, AZ), January 6, 1922.

[21] Sohoni, “Unsuitable Suitors.”

[22] “How Mixed Chinese-Western Couples Were Treated a Century Ago,” Asia Society, January 10, 2017, https://asiasociety.org/blog/asia/how-mixed-chinese-western-couples-were-treated-century-ago.

[23] California Code Amendments, Chapter 41, Section 1 (1880).

[24] “Becomes a Real Chinese,” Kansas City Star (Kansas City, MO), June 15, 1907; “Takes up Dragon; Renounces the U.S.,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), June 16, 1907.

[25] Ayres, “Relics Dug from the Ruins.”

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ayres, “Relics Dug from the Ruins”; Thomas V. Quirk, “Mark Twain,” Britannica, last updated April 17, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mark-Twain.

[28] Robert Bogdan and Todd Weseloh, Real Photo Postcard Guide: The People’s Photography (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006), 13.

[29] Ibid, 13-14; Robert W. Bowen and Brenda Young Bowen, San Francisco’s Chinatown (Charleston, Chicago, Portsmouth, San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing), 8.

[30] Bogdan and Weseloh, 2.

[31] Ibid, 2.

[32] Ibid, 14.

[33] Ibid, 14.

[34] Ibid, 8.

[35] Ibid, 8-9.

[36] In Appendix 2 of Bogdan and Weseloh’s Real Photo Postcard Guide, the authors provide a guide to postcard back designs by brand, recording the earliest known date of each. Eleven of the fourteen postcards are on Azo brand paper—the word “Azo” is seen along the border of the stamp boxes. All of these are accompanied by a little triangle in each of the corners of the stamp box, a style Azo used between 1907 and 1925. Other distinguishing features of the postcard back, like the presence of a line dividing the “Correspondence here” and “Name and address here” sides, the use of “Correspondence here” and “Name and address here” as opposed to the shorter “Correspondence” and “Address” titles used later, and the two different fonts the word “Post Card” is printed in at the top, date the production of the paper to sometime between late 1907 and mid 1909; ibid, 222-223.

[37] The three Kruxo postcards feature two different back designs. These three postcards are the two duplicates where Wong Sun Yue is sitting and Ella May is standing inside the shop and the individual horizontal close shot of the couple standing inside the shop. The two different back designs are distinguished by the use of “For address only” as opposed to “Address only.” This paper was likely produced between late 1907 and mid 1908. I have identified these three as Kruxo photo postcard paper because of the ornate “Post Card” wording, lack of stamp box, and the “Correspondence here” and “For address only” words; ibid, 231.

[38] “Offices and Stores to Let,” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, CA), January 9, 1908; “Help Wanted—Male,” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, CA), June 13, 1911; “Help Wanted—Male,” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, CA), April 11, 1917.

[39] Bogdan and Weseloh, 53-54.

[40] Bowen and Bowen, 13.

[41] “Finding Aid to the San Francisco Police Department Records, 1870-1983 SFH 61,” Online Archive of California, accessed April 14, 2022, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833tdg/dsc/?query=john%20kytka#ref174.

[42] “Pompeii in America,” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, CA), August 2, 1909.

[43] “Sister of Howard Gould’s Wife Now Chinatown Queen.”

[44] “News of Women,” Tucson Citizen (Tucson, AZ), January 25, 1915.

[45] “News of Women.”

[46] Vox, “The surprising reason behind Chinatown’s aesthetic,” YouTube, May 10, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EiX3hTPGoCg.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Standard Guide to San Francisco, with Description of the Panama-Pacific Exposition (San Francisco: North American Press Association, 1915), 29.

[49] Ibid, 27.

[50] California for the Tourist: The Charm of the Land of Sunshine by Summit Sea and Shore (San Francisco: Southern Pacific, 1910), 17.

[51] “American Wife of Chinese Eulogizes Husband’s Race,” The Grand Rapids Press (Grand Rapids, MI), April 7, 1915.

[52] Hitt, “Mystery in Death.”

[53] Millie Robbins, “Strange Tale of Sisters,” San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, CA), February 20, 1966.