Preserving the Past: Exploring the Heart Mountain Reunions

By: Julia Chaffers '22

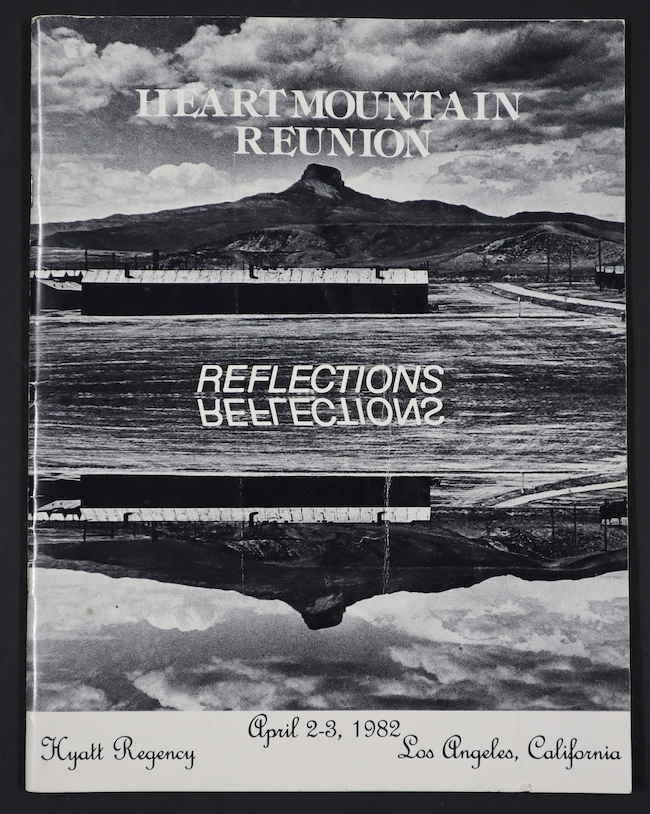

On April 2, 1982, more than eight hundred people gathered at the Hyatt Regency hotel in Los Angeles. A letter from the city’s mayor welcomed attendees to the city, where a weekend of programming awaited. For many of them, it had been forty years since they had seen each other. But the people who had gathered for this reunion were not reminiscing on happy days gone by. Instead, they had come together to reconnect with some of the few others who experienced what they had survived: Japanese internment during World War II.

Princeton holds a collection of seven yearbooks from reunions of Japanese Americans who were held at Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming during the war. Created during the Heart Mountain reunions across the West coast from 1982 through 1997, these yearbooks show how the Heart Mountain community reflected on its past experience and worked to maintain community decades later. Created by former internees, the yearbooks grant us valuable insight into the experience of internment at Heart Mountain. Through poetry, essays, and photographs, these yearbooks work to recapture what it was like to live at Heart Mountain. Later yearbooks, from 1989 onward, focus more on commemorating the reunions themselves, featuring content from the contemporary gatherings more than from the camp. Both kinds of yearbooks help us learn about the legacies of Japanese internment.

Historical Background

On February 19, 1942, ten weeks after the United States entered World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which empowered the Secretary of War to “prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject” to those commanders.[1] In practice, this authorized the military to exclude Japanese Americans from designated military zones on the West coast. After some voluntary evacuation, the army began the forced relocation of Japanese Americans from their homes into internment camps.[2] Between December 1941 and September 1947, the United States incarcerated over 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry, under the guise of its war powers.[3] Two thirds of those incarcerated were American citizens, and the majority of the others were permanent residents.[4] These Japanese Americans were held in ten internment camps spread across remote areas in California, Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, and Arkansas. Heart Mountain, located in northwest Wyoming, was open from June 1942 to November 1945.

Beginning in the 1970s, former internees and their descendants began organizing for reparative action from the federal government. In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to review how internment became government policy and recommend redress. Through archival research, witness testimony, and input from scholars, the CWRIC published its report, Personal Justice Denied, in February 1983.[5] The report concluded that “the promulgation of Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it—detention, ending detention and ending exclusion—were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”[6]

While many internees and former internees had for years argued that internment was a racist and unjust policy, the CWRIC’s report represented the first time the federal government admitted to its wrongs. The report also gathered archival and experiential evidence that traced the development and impact of internment. After the report, President George H.W. Bush formally apologized for internment and Congress passed restitution legislation, distributing $20,000 to each surviving Japanese American who experienced internment.[7] The 1990 Heart Mountain reunion yearbook includes the text of President Bush’s letter, which reads in part: “A monetary sum and words alone cannot restore lost years or erase painful memories; neither can they fully convey our Nation’s resolve to rectify injustice…. But we can take a clear stand for justice and recognize that serious injustices were done to Japanese Americans during World War II.”[8]

The reparations were intended to address the property and income loss that resulted from internment; the CWRIC estimated that in 1983 dollars, internees lost $1.3 billion in property and $2.7 billion in net income.[9] The attention that activism from Japanese Americans and the CWRIC report brought to the importance of Japanese internment likely contributed to the emergence of the Heart Mountain reunions beginning in 1982.

Experiences at the Camp

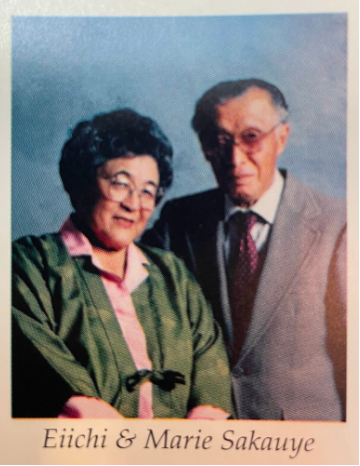

“When I first saw it…when we first got off that long train ride, I thought, ‘What a barren and desolate place this is.’ We got there on an evening in early September. There wasn’t a farmhouse or building near or within sight, but there were sentry towers and barbed wire fences that surrounded the tar-papered barrack city. All search lights and military guns were pointed inward.” — Eiichi Edward Sakauye, “Heart Mountain Memories”[10]

Living Conditions

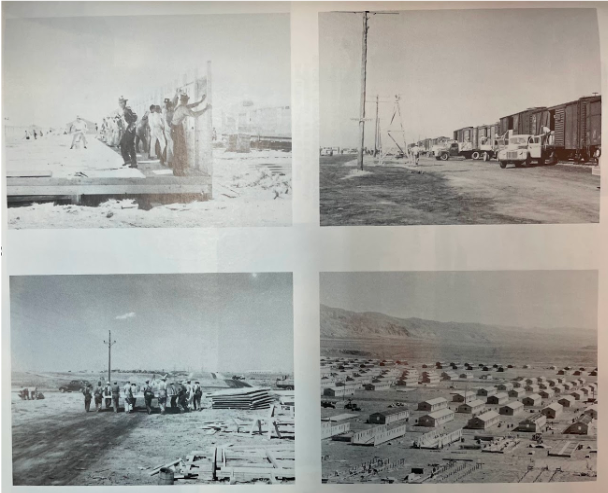

The first two reunion yearbooks, from 1982 and 1985, contain essays like Eiichi Sakauye’s along with poetry and photographs to recreate life at Heart Mountain. These sources, which recount the experience of internment from former internees’ perspectives, help us understand what it was like to live at Heart Mountain. Sakauye’s essay paints a picture of camp life. He describes how there were 11,000 residents living in thirty blocks. Each block had 24 barracks, a mess hall, and bathroom units. Within the barracks lived four family units of various sizes, with each family occupying one open room. Sakauye recalls, “Each unit was just one big room with no walls for privacy. Everybody had to string sheets or curtains to make separate areas. Across from us there was a family of 12.” Sakauye describes that even these meager furnishings were not prepared for the internees when they first arrived. Instead, people had to acquire their own cellutex (cardboard) to line the walls for warmth, and order their own materials from Sears Roebuck and other companies. As Sakauye explains, “trainloads of people came so frequently” that the War Relocation Authority (WRA) could not finish the barracks in time.[11]

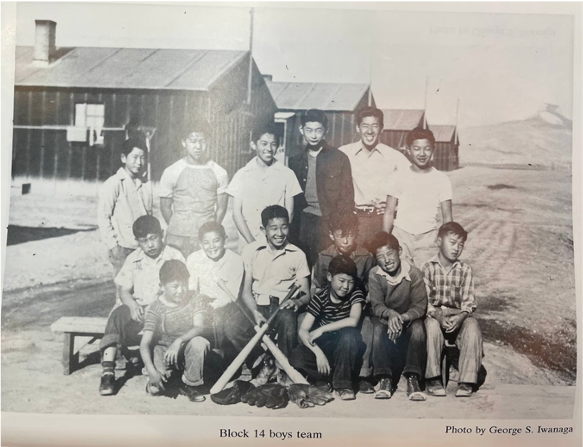

Sakauye notes that his barrack was “used as a photography lab most of the time.”[12] This detail is significant, as the military banned photography from internment camps until 1943.[13] The ban on photography testifies to the power of photographs to inform people about the injustices being carried out in the camps. In this context, Sakauye’s photography from 1943 onward represents an important act of testifying to the experience of internment for generations to come.

While many of the photographs in the yearbooks are uncredited, two photographers are identified in the 1997 yearbook: Jack Richard and George S. Iwanaga. Richard was a white journalist and photographer from Cody, Wyoming, nearby Heart Mountain.[14] Iwanaga, originally from Fresno, California, was interned at Heart Mountain from 1942 to 1944 when he was in his early twenties.[15] Richard and Iwanaga provide valuable depictions of Heart Mountain.

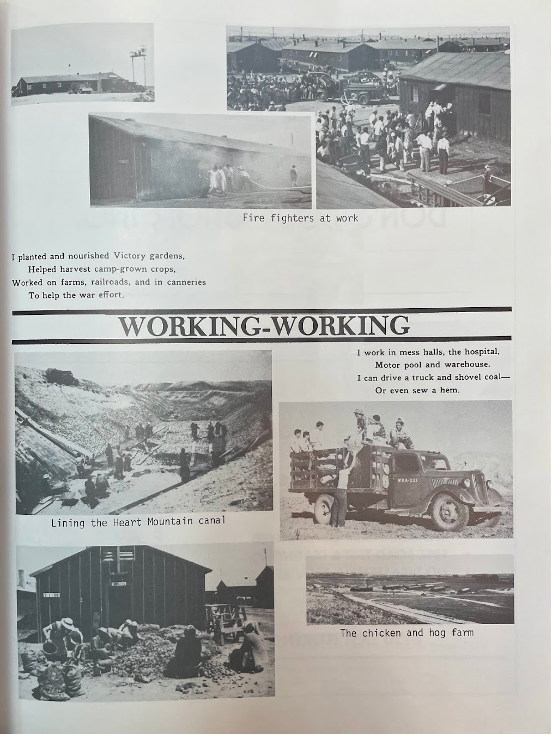

Labor

Internees worked a number of occupations at Heart Mountain, including constructing a canal on the property, working in mess halls, delivering coal, and farming.[16] Sakauye describes the experience of coal workers: “Coal for heating was really important at Heart Mountain during those long, cold Winters. The coal came in great gondolas and the camp coal crew had to unload it by hand. That was really hard work. We had a coal strike a couple of times because they wanted better pay, shorter hours, and so forth.” Sakauye’s account of compensation for workers shows that this dissatisfaction was not uncommon: “Salaries were $12.00, $16.00 and $19.00 per month for a 40 hour week. All workers received $3.75 per month for clothing allowance which didn’t buy very much.” Sakauye worked as “Farm Superintendent,” and helped Heart Mountain grow a diverse range of crops that supported the mess halls on 1,500 acres of land. Sakauye attests to the impact that his expertise left on the communities for generations: when he visited the area years later, the innkeeper remarked that “You people opened our eyes and showed us what can grow in this place.”[17]

The governing structure of Heart Mountain reflected another example of the marginalization of internees. According to Saukaye, “The head of each department were all Caucasians, and under each Caucasian, there were the evacuees. In many cases the evacuees knew more than their superior, and they did a much more efficient job. Usually the evacuee specialized in that particular field, whereas their department head had not.”[18] This hierarchy reflects the oppression that internees faced while held at Heart Mountain.

Building Community at Heart Mountain

“For those of us who stayed at Heart Mountain, jobs were found, recreational activities created and routines established. Heart Mountain was like a small city only its residents were made up of persons of Japanese ancestry from all walks of life, ages and education.”

“The school gym became the social center of the younger generation and within it were held dances, basketball games, the class play, movies and meetings. During the long, cold winter this was one warm place where youngsters could gather and enjoy themselves.”

Despite the hardship internees faced in the camp, the Heart Mountain yearbooks emphasize the community they built and joy they found. Children and adults formed sports teams, including baseball and basketball teams. The school hosted dances and balls for community members. Boys joined boy scout troops as well. There were churches on site where community members gathered.[21] Sakauye also describes how people played on the skating rink—a football field filled with water—in the winters, and in a swimming hole in the summer. People also explored the canyons around the camp, fished in the lake, and hiked around the surrounding landscapes.[22] These photographs and recollections show how people interned at Heart Mountain built a community within the camp, creating spaces for joy and normalcy.

The reunion attendees were mostly teenagers during their internment. The class photographs in the 1992 yearbook include images of the class of 1943 through 1951, meaning that in 1944 attendees were in fifth through eleventh grade. A letter by George Hanada in the 1994 yearbook references the differing experiences of older and younger people at Heart Mountain. Hanada writes that the “older people were clinically shocked, bewildered, saddened and angered. Though the shock, bewilderment, sadness and anger has been tempered with time, it still remains. The young children were also bewildered and saddened by the relocation and loss of many friends, but quickly adapted and made new friends.”[23] Hanada’s letter suggests that younger internees had an easier time adapting to life in the camp and building connections with their peers.

“Never forget”: Collective Memory of Trauma

“This reunion will enable all of us to join fellow evacuees and former neighbors as we renew old acquaintances and relive those trying years. It holds mixed emotions for us all, but it is important that we never forget and that we commit ourselves to never allow this tragedy to happen again.”

The above letter from California Representative Norman Mineta encapsulates the balance these reunions struck between commemoration and celebration. Mineta, the son of Japanese immigrants, was himself interned at Heart Mountain. In gathering former internees together forty to fifty years after their time at Heart Mountain, the reunions both commemorated the collective trauma they experienced and celebrated the enduring community and joyful memories also associated with the camp. Events from the reunions illustrate this nuance. One component of the yearbooks and the reunions themselves was reflecting on the history of the camp. The first two yearbooks, from 1982 and 1985, only featured material from the camp. By contrast, later yearbooks only included photographs and descriptions of the reunions’ events—some others included a mix of the two. These shifting emphases show how reunions organizers worked to navigate the complexities of bringing people together around a shared experience of trauma.

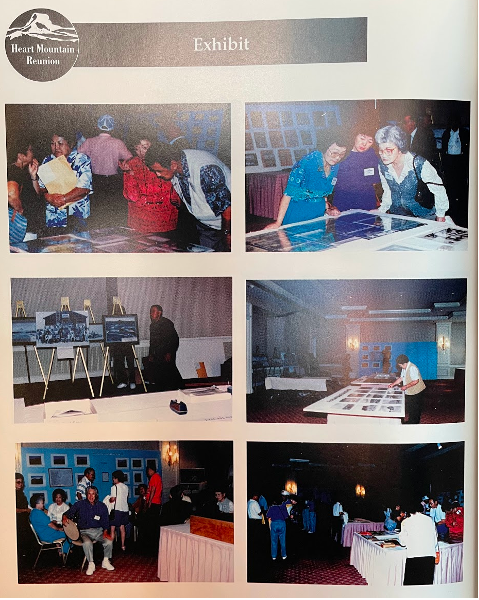

The reflections on history were two-layered. First, within the reunions themselves were exhibits featuring photographs from Heart Mountain. Displayed on poster boards and tables, these photo exhibits allowed reunion attendees to revisit memories at the camp, positive and negative. The schedule of events from the 1989 reunion, for example, allotted a six-hour window for attendees to visit the exhibit. These exhibits show that preservation of history was an important purpose of these reunions.

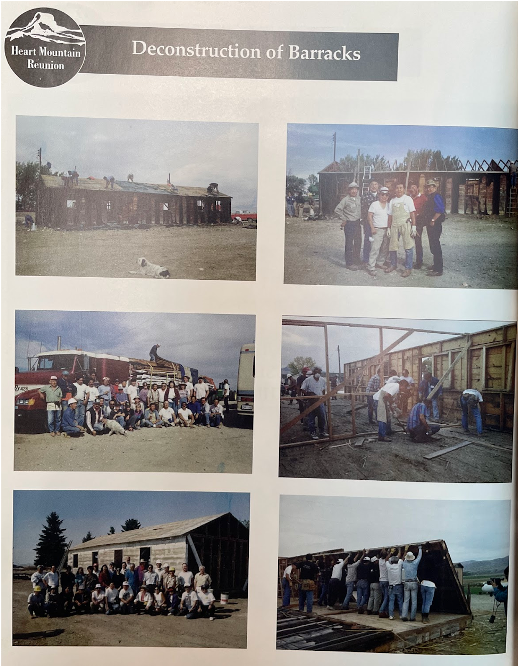

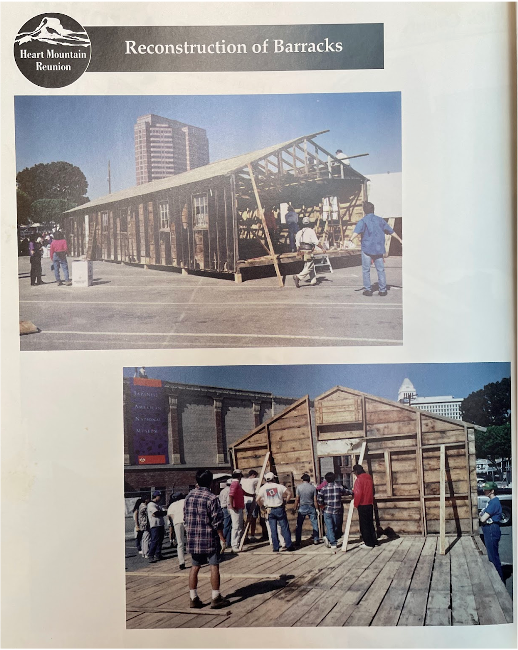

The reunions also showed examples of former internees returning to Heart Mountain. The 1994 yearbook, for example, includes photographs from a project to create a museum in part of the former camp. The yearbook includes clips from newspapers that covered the return of former internees to Heart Mountain to participate in the museum’s construction. Headlines read, “Japanese Americans Revisit Their Painful Past,” and “Heart Mountain work brings ‘catharsis,’” showing the significance of this project to former internees.[25]

A primary purpose of the reunions and yearbooks was to enable former internees to reconnect and come together in community once more. A description of the process by which reunion organizers coordinated the 1990 reunion for the Heart Mountain class of 1949 shows how former internees brought their peers together. The twenty-person planning committee contacted classmates by phone and letters, mailing out 125 invitations. They also placed newspaper advertisements in San Francisco, San Jose, and Washington state, as well as in two Los Angeles-based newspapers, Pacific Citizen and Rafu Shimpo, that focused on the Japanese American community.[26] Their publicity efforts illustrate how close the former internees remained: first, the committee was able to procure the contact information of their former classmates. Secondly, the newspapers they chose to place advertisements in show that many former internees still lived on the West Coast, primarily in California. This suggests that many Japanese Americans returned to their home communities after the war and rebuilt their lives there. The locations of the reunions, all of which were in California, Nevada, and Washington state, also demonstrate the continued closeness of the Heart Mountain community.

Recurring events at the reunions allowed participants to reconnect with old acquaintances and meet new people. Activities included mixers, class photographs and individual portraits, a golf tournament, and a banquet with musical performances. The 1989 and 1992 yearbooks are solely dedicated to the events of the reunions, with photographs only from those gatherings rather than from the camp. These yearbooks present another type of memory creation: cultivating a new set of memories with the formerly interned community. The yearbooks that came out of these reunions gave attendees new experiences to associate with their Heart Mountain community. They were able to reconnect with the communities they had built during their internment, and meet others who shared their experiences during World War II.

A letter from George Hanada in the 1994 yearbook illustrates this connection. After recalling the “concentration camps with barbed wire, armed guards and machine gun towers,” Hanada expresses his appreciation for the reunion. He writes, “Fifty two years later, at reunion number five hosted by San Jose, we were again able to renew old friendships and enjoy the camaraderie we shared. It was great to spend a few days with friends and renew old acquaintances and to reminisce, for there was a period of time that we did share and suffer together.”

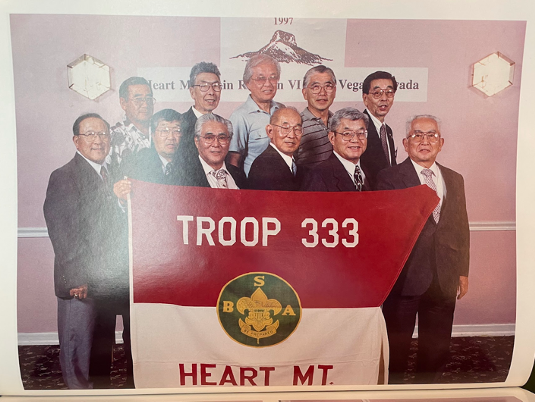

Photographs from the 1997 reunion encapsulates this idea by including photographs of attendees in groups from shared camp experiences. For example, attendees posed with fellow members of their barracks blocks at the camp. In another example, a group of attendees who were in Boy Scout Troop 333 at Heart Mountain posed with their troop flag. These photographs show how the communities they cultivated at Heart Mountain continued to resonate fifty years later, and continued to bond attendees as they returned for reunions. These photographs of reunion attendees decades after internment demonstrates reunion organizers’ efforts to create new artifacts of shared memory for the Heart Mountain community.

The Heart Mountain reunion yearbooks provide many new insights into collective memory of Japanese internment. On one level, these sources teach us about internees’ experiences of internment, through photographs from Heart Mountain and written texts describing and reflecting on people’s time in the camp. The inclusion of these elements shows how the Heart Mountain community worked to preserve these experiences for their peers and for a wider audience. The yearbooks as artifacts from the reunions themselves also show us how the former internees used these reunions to both reflect upon the shared trauma they faced and celebrate the resilient community they built at Heart Mountain despite the oppression they experienced. On both of these levels, as sources that speak to experiences of internment and as sources that demonstrate efforts to commemorate those experiences, these yearbooks are valuable resources that add to our understanding of the legacies of Japanese internment.

[1] Executive Order 9066, February 19, 1942, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, National Archives.

[2] “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942),” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-9066.

[3] Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), xv, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnm2s.

[4] Personal Justice Denied, xvi.

[5] Personal Justice Denied, xvii.

[6] Personal Justice Denied, xviii.

[7] Personal Justice Denied, xx-xxi.

[8] Heart Mountain Class of 1949 Reunion Yearbook (1990); Heart Mountain Reunions, 1982-97 Collection of Programs and Materials; Western Americana Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library, https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99125432999406421.

[9] “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942).”

[10] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook; Heart Mountain Reunions, 1982-97 Collection of Programs and Materials; Western Americana Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library, https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99125432999406421.

[11] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[12] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[13] May-Ying Lam, “‘Colors of Confinement’: Japanese Internment Camp Photographs by Bill Manbo,” Washington Post, August 31, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/colors-of-confinement-japanese-internment-camp-photographs-by-bill-manbo/2012/08/31/7438da6a-f314-11e1-adc6-87dfa8eff430_story.html.

[14] “MS 089 Jack Richard,” McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, http://library.centerofthewest.org/digital/collection/JRS.

[15] “George S. Iwanaga Papers,” Online Archive of California, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c83t9ns9/.

[16] Heart Mountain 1982 Reunion Yearbook; Heart Mountain Reunions, 1982-97 Collection of Programs and Materials; Western Americana Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library, https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99125432999406421.

[17] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[18] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[19] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[20] Heart Mountain 1982 Reunion Yearbook.

[21] Heart Mountain 1982 Reunion Yearbook.

[22] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[23] Heart Mountain 1994 Reunion Yearbook; Heart Mountain Reunions, 1982-97 Collection of Programs and Materials; Western Americana Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library, https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/99125432999406421.

[24] Heart Mountain 1985 Reunion Yearbook.

[25] Heart Mountain 1994 Reunion Yearbook.

[26] Heart Mountain 1990 Reunion Yearbook.

[27] Heart Mountain 1994 Reunion Yearbook.