“Pioneer Photographer of the Whole Southwestern U.S.”: The Adventures of Ben Wittick

By: Juliet Sturge '23

Access Wittick's digitized photo albums via Princeton University Library.

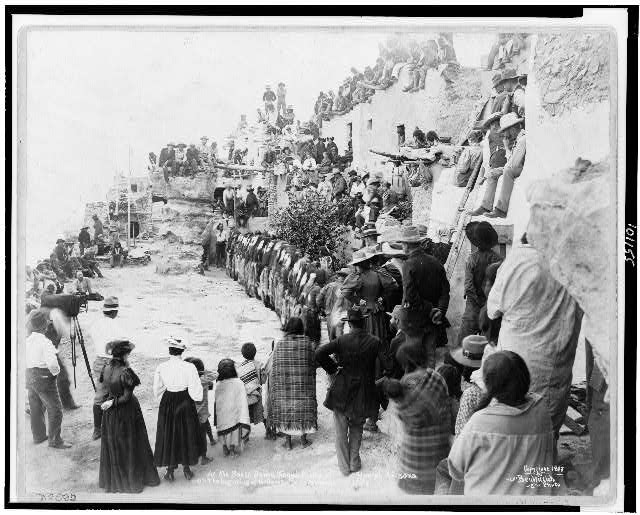

Ben Wittick lived and died to capture the best possible photographs. For decades, he visited Hopi villages yearly to take photographs of life there, including the notorious Snake Dance. A Priest warned Wittick that because he had not been initiated his presence would result in death. The prophecy came true in 1903 when he died after being bitten by a snake he was planning to take to his Hopi friends. [1] The tragic irony of his death was a momentous end to a career full of exploration and adventure.

Death shall come to you from the fangs of our little brothers.

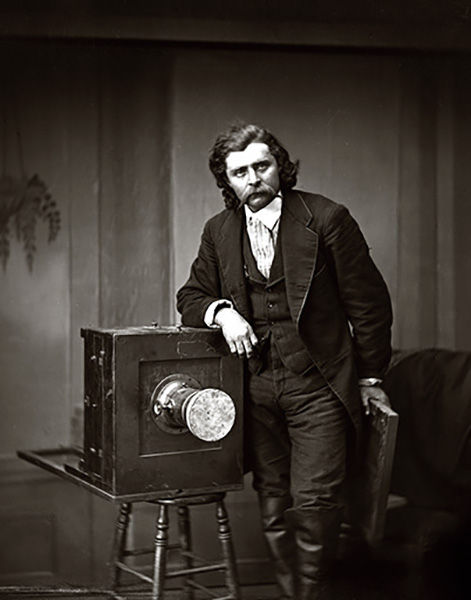

George Benjamin Wittick was born in Huntington County, Pennsylvania in 1845 and later moved to Illinois with his family. In 1862 he enlisted in the Second Minnesota Mounted Rangers, a voluntary cavalry regiment of the Indian Service Division, which perhaps began his interest in Native communities. [2] He later opened a photographic studio in Moline, Illinois and was then offered a job by the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad as their official photographer. After going West with the railroad in 1878, leaving his wife and six children behind, Wittick would never return to the Midwest permanently. Instead, he moved around the Southwest taking photographs and seeking adventure with occasional trips to visit his family. [3]

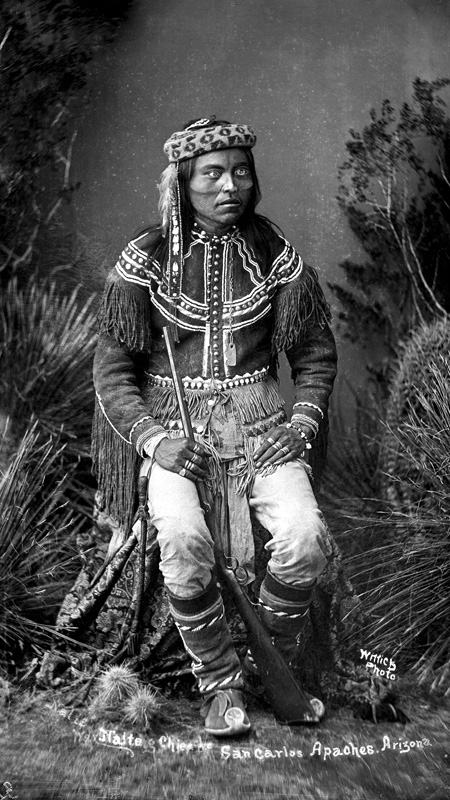

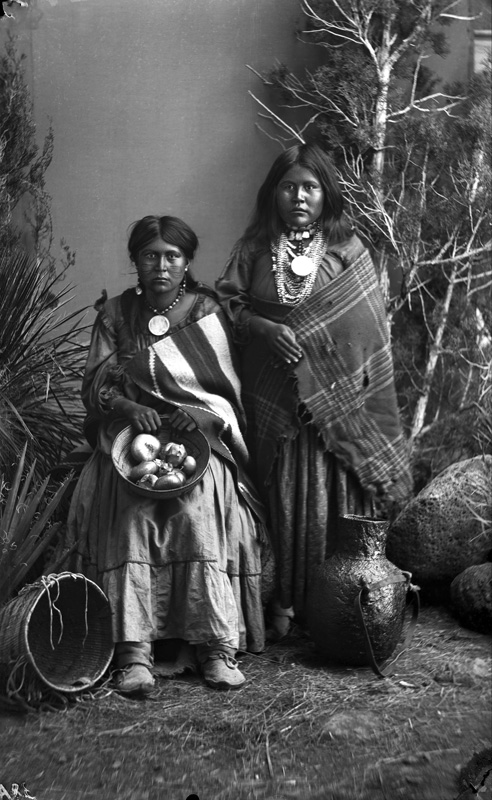

Wittick began taking many photographs of Native peoples starting in 1878 on the road with the Railroad company before moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The photographs can be divided into two distinct categories: field photographs and posed portraits.

Like many photographers of Native life during the late 19th century, Wittick brought props and backdrops along with him to stage portraits of his subjects. Wittick’s staged photos reveal not only his own vision, but also the acceptance of the romanticized and constructed view of Native people by his customer base which alludes to the commonly held beliefs of Native people by the wider U.S. population at the time.

While it may seem that his field photographs more accurately document the daily life and livelihood of the Native communities, Patricia Broder in her book Shadows on Glass: The Indian World of Ben Wittick states they are “a composite of reality and illusion, fact and fantasy” not unlike his staged portraits. [4] The uninhibited access Wittick gained in many communities is revealing of the level of trust and assimilation the Native groups had in him. His son Tom, who accompanied him on many of his travels, proclaimed him and his first partner, R.W. Russell, to be "the pioneer photographers of the whole southwestern U.S.". [5]

A composite of reality and illusion, fact and fantasy.

Princeton’s Western Americana Collection houses two very distinctive, beautiful Ben Wittick albums that showcase some of the breadth of his photography portfolio. The first album, dated around the 1880s, features 19 albumen photographs of various subjects and landscapes from Hopi, Acoma, Navajo, and Apache areas. The second album is much more cohesive in its organization and includes 9 photographs of Hopi villages from an unknown date. Given that Wittick visited the Mesas every August to witness the Snake dance from his initial trip in 1880 to his death in 1903, dating the photographs can prove very difficult. [6]

1880s ALBUM

The first album is much smaller, although the photos range in size from 4 ⅜ x 7 ⅜ to 5 ¾ x 8 ½ in, about the size of boudoir images from this time period. While the exact purpose of the album is unknown, the inconsistencies in both the size of the photographs and the content of the photos themselves supports the idea that it was created for personal use. The leather binding is a generic folio that was probably bought and then the photos pasted in later, as the uneven edges of the cut-out photographs reveal it was not a professional’s work. Despite the album being dated between 1883-1885 by the dealer and subsequently Princeton’s catalogue, no clear evidence supports this identification.

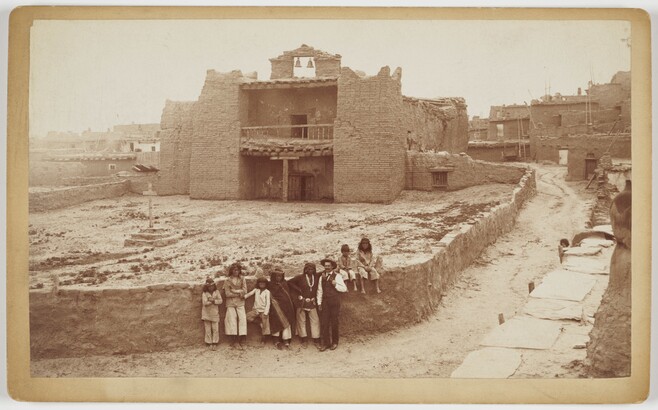

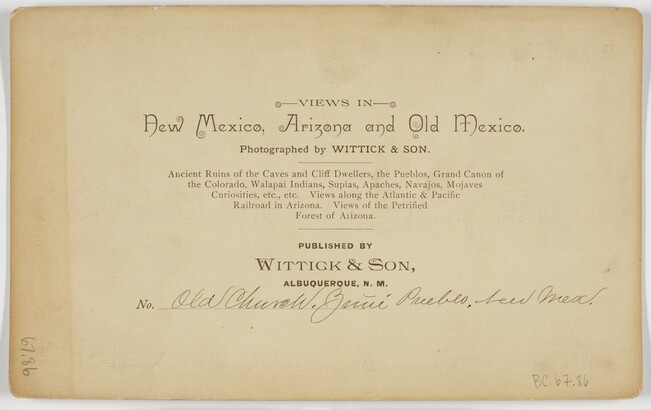

What will from here on out be referred to as the 1880s album, the smaller of the two, consists of many photos that can be traced elsewhere. The first photograph of the album, “Pueblo of Zuni, N.M. '' shows the Old Zuni Mission Church that still stands today. The Amon Carter Museum has a boudoir card print from the same negative — evidence that the negative created multiple prints that were used for different purposes. The back of the card reads the same as many of the other boudoir cards that match photos from the album: “Views in New Mexico, Arizona and Old Mexico: Ancient Ruins of the Caves and Cliff Dweller, the Pueblos, Grand Canon of the Colorado, Walapai Indians, Supias, Apaches, Navajos, Mojaves Curiosities, etc., etc. Views along the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad in Arizona. Views of the Petrified Forest of Arizona” (See below).

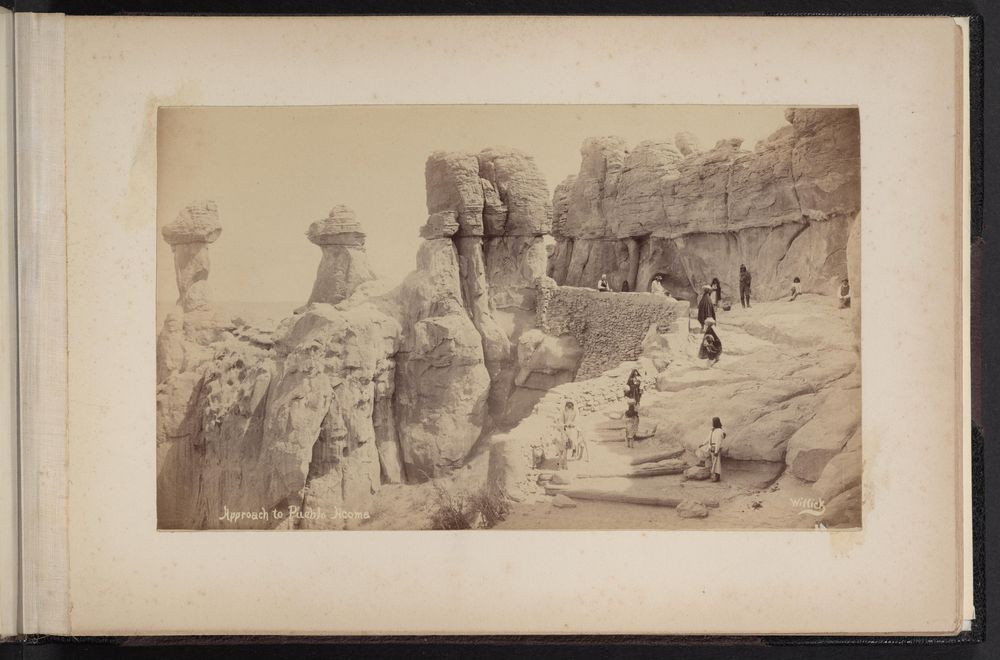

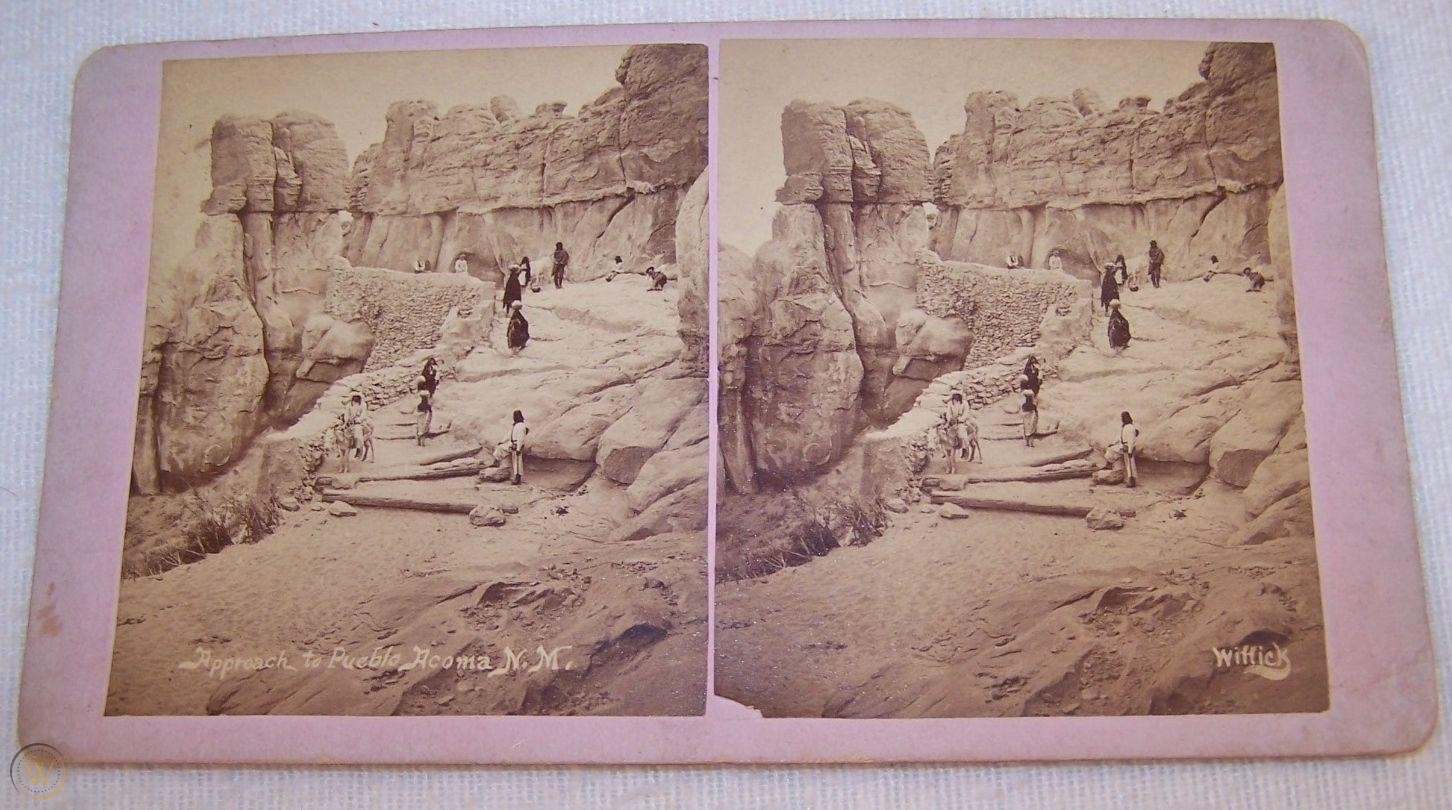

“The Approach to Pueblo Acoma” and “View in Acoma Pueblo, N.M.” are two other photos that show up elsewhere apart from the album.

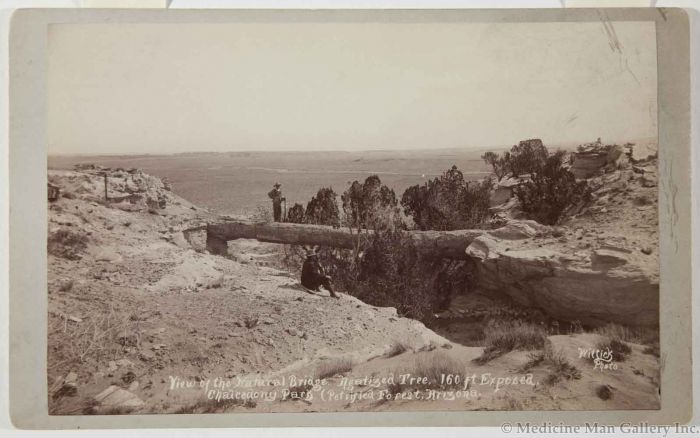

Interestingly, the photo of the Agate Bridge exists in an identical print made from the same negative outside of the album but with a completely different caption written on the negative. While the album version reads: “(105 feet) Agate Bridge. Petrified Forest. Arizona.” The individual boudoir card example reads: “View of the Natural Bridge, Agatized Tree, 160 ft Exposed, Chalcedony Park (Petrified Forest, Arizona.”

Given that the prints are so similar they must have been from the same negative, even down to the position of the subjects, the two captions must have been written on the same negative. The Palace of the Governors Photo Archives in Santa Fe has the negative of the photo with the second caption, meaning that the caption that appears in the photo in Princeton’s album was most likely a mistake that was erased and rewritten after the print had been made. This offers a glimpse of the photo creation process and the mistakes that could be made while working in the field.

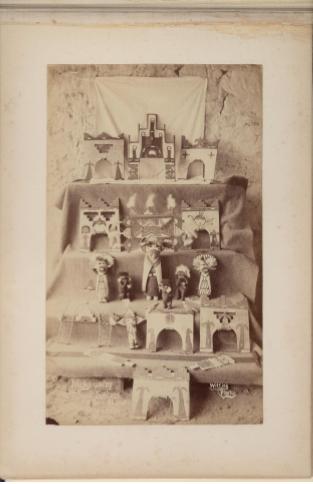

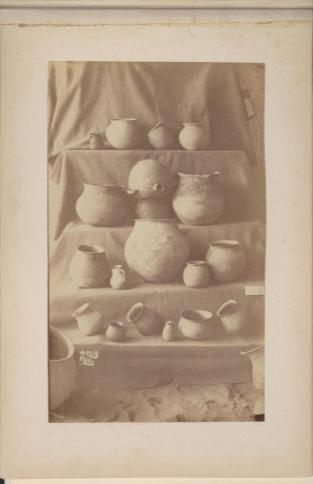

The inclusion of photos of Hopi pottery, masks, rattles, and katsina figures seems out of place among the entire album but makes sense among Wittick’s larger body of work. He was incredibly interested in Native American craftsmanship, taking photos of pottery, baskets, masks, etc. along with cultivating his own personal collection of objects from his travels. In his reports of the ceremonies and rituals, especially in Hopi villages, he often took extensive notes on the artistic objects that contributed to the events like costumes, altars, prayer sticks, etc.. [7] The photos read almost like advertisements for the abilities of the Hopi artists who created them and could entice visitors to buy these objects. While not many of the prints from the same negatives of the prints in the album could be found, there are many similar photos of Hopi art also taken by Wittick.

The writing on the negatives, of both Wittick’s name and captions for many of the photographs, is further evidence that the photos could have been individually sold then later compiled into the album by the buyer. Only two photographs lack Wittick’s name, one of Acoma’s Enchanted Mesa and the final photo of Fort Wingate Officers, which leads one to question the photographer’s identity although the subject matter and inclusion into the album suggests that they were taken by Wittick. The inconsistencies of the signatures, some reading “Wittick” and others “Wittick Photo,” could also be evidence that the photos were taken at different times.

Scholars cite Ben Wittick’s restless nature which is what led to his endless adventures into remote areas and desire to capture Native life and secret ceremonies on camera. [8] His desire for adventure is somewhat contrasting to his staged individual and group portraits, from which he is most well-known. This disjunction could be evidence that Wittick was filling the desire of the market with his staged photographs, over presenting his genuine views on Native people. Only two photos from all 28 included in both albums that mirror this style: “Apache baby” and “Moqui Indian Girl.”

Both photos, included in the smaller album, have staged sets; although they lack the elaborate props and costuming Wittick often used. While landscape shots and seemingly candid shots are also included in Wittick’s larger oeuvre, the lack of staged photos in the two albums is a departure from being completely representative of the photos Wittick took of Native peoples.

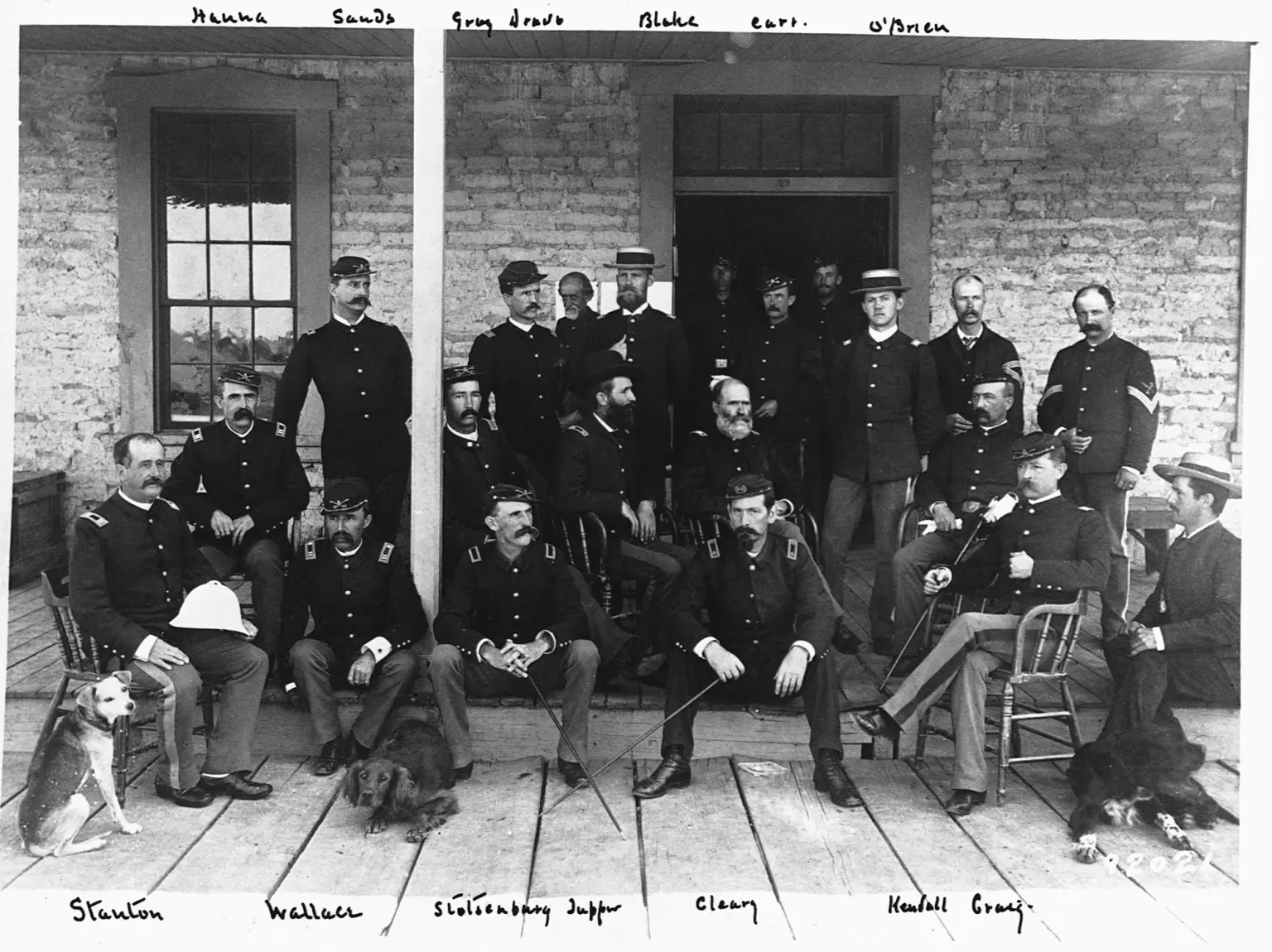

Fort Wingate Officers

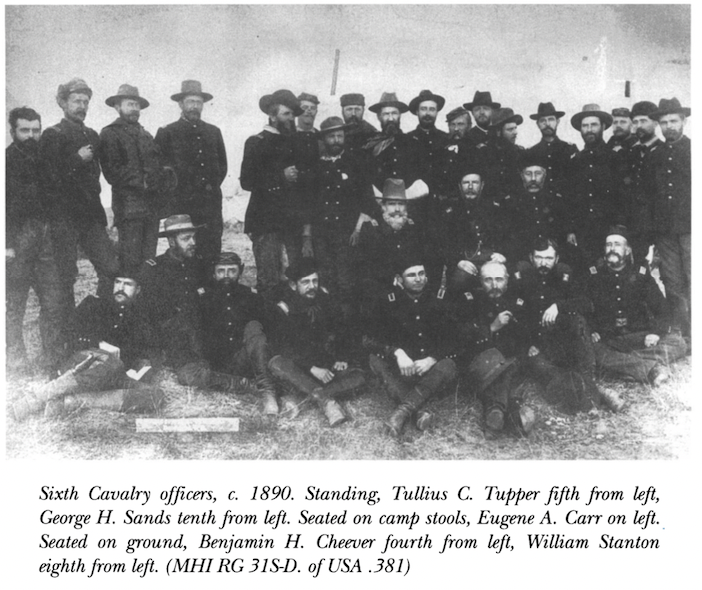

One of the most interesting parts of the 1880s album is the inclusion of the final photo which depicts 21 officers at Fort Wingate, a prominent military post near Gallup, New Mexico, where Ben Wittick’s longest standing studio was located.

The photo is the only one in the album not to depict some aspect of Native American life or culture. It is also the only photo in the album that includes a handwritten pencil caption on the album page: “Fort Wingate, N.M., early 1880s - officers and non-coms.” Not only does the handwriting contrast the other examples of Wittick’s handwriting that are written on many negatives, but the information is also incorrect as the photo was not taken in the early 1880s. This is further evidence that the album was most likely compiled by a private collector.

The photo’s attribution to Wittick is purely circumstantial — given that it was included in an album of primarily identified Wittick photographs and was taken in a place to which Wittick was connected. Unfortunately, it is often difficult to conclusively determine who took a photograph if the documentation does not exist. Wittick worked with several partners throughout his career, as well as his sons Tom and Archie, any of whom could have taken many photos attributed to Wittick or it could have been an completely unrelated photographer.

Another copy of the photo comes from Corbis via Getty Images with no further evidence of the image’s provenance (Below on left). This iteration of the photo does include several names that helped exponentially with the identification of the officers.

Twelve full names could be identified as members of the Sixth Cavalry at Fort Wingate, including Captain William Stanton, Captain William M. Wallace, Lt. John M. Stotsenburg, Captain Tullius C. Tupper, First Lt. Henry M. Kendall, First Lt. Louis A. Craig, Lt. Robert Hanna, Lt. Charles E. Sands, Lt. Alonzo Gray, Lt. Edward E. Dravo, Colonel Eugene A Carr, and Colonel John Y. F. Blake.

There are very few photos of the Sixth Cavalry officers together available, with only one other photo helping with group identification (Above on right). In researching military records, published diaries, and newspaper articles, it was revealed that all of these men were present together at Fort Wingate for only a very short time frame.

Most revealing to the date of the photograph were the presences of Lt. Sands who was assigned to the Sixth Cavalry on January 10, 1889, before being discharged in 1892 and Colonel Blake who was assigned to Fort Wingate in November of 1887 and resigned from his post on February 9, 1889. [9, 10] The photo could thus have only been taken in the one-month period between January 10 and February 9 in 1889.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that Getty Images does not identify the photo as Ben Wittick although the negative number is visible and doesn’t rule out the photo as being taken by Wittick. The Palace of the Governor’s Collection has a gap in their archive of Wittick negatives from 88274 to 102033; the Fort Wingate photo is numbered 92021. Many of the available negatives from directly before and after #92021 depict scenes of Fort Wingate which further supports the accreditation of the photo to Wittick.

The provenance of the 1880s album is mostly a mystery. The album can be traced back only as far as a 2007 auction from Heritage Auctions. It was bought from a Wyoming dealer by the Andrew Smith Gallery in 2008 before being sold to Princeton University in 2016.

An advertisement for Wittick’s photographs from around the time of the album reveals the ways in which he enticed buyers to purchase his photographs. The apparent randomness of the album, which includes many different photo types and photos from many areas, lends itself more to the view that the album was created by a tourist or a fan of Wittick’s work instead of being assembled by a Native person whose tribe was represented in any of the photos. Due to the lack of information nothing can be conclusively determined.

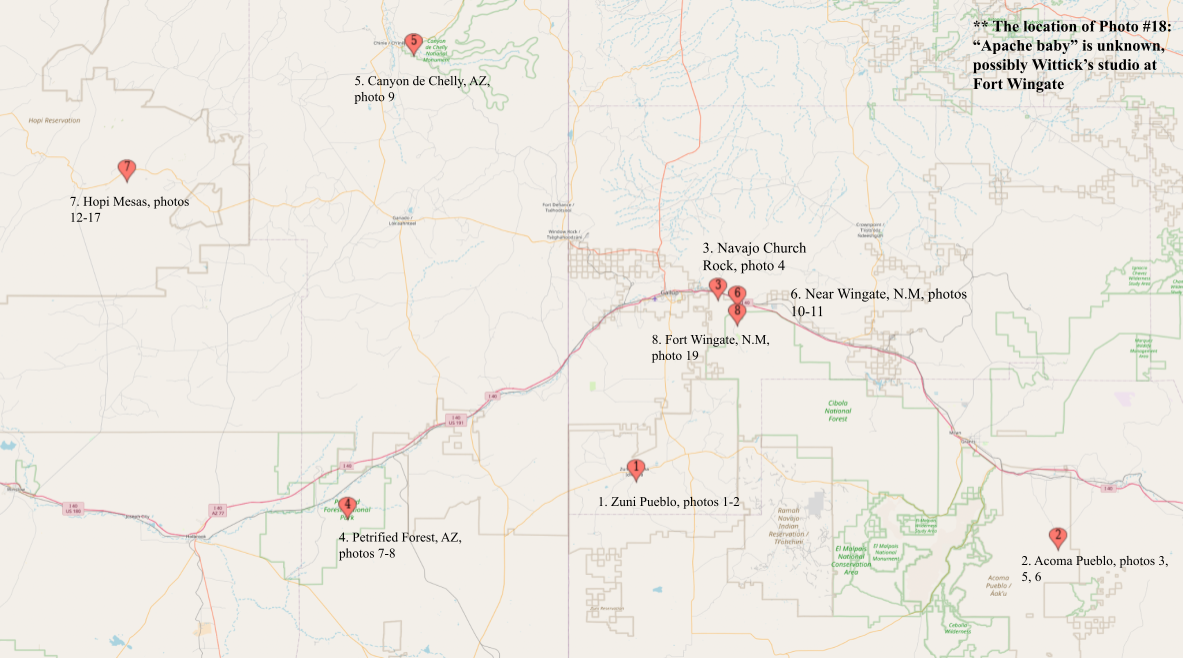

While the selection of the photographs seems somewhat arbitrary, the photos are organized, generally, by location. Starting with Zuni, then progressing until the final photo near Wittick’s studio at Fort Wingate, the photos seem to evenly spread across Arizona and New Mexico. Although the thought process of the assembler will remain a mystery given there is no supplementary information on the creation of the album, many possible approaches can be explored.

The ordering of the photos helps supplement the lack of information provided by the brief or non-existent captions. Each photo gets the context of the photos that surround it which assists in creating a narrative of Wittick's travels. The album follows him from Pueblo to Pueblo across the West and then returning to his home base at Fort Wingate.

It is plausible that the assembler simply chose a variety of Wittick’s selection of photographs, the abundance of Hopi photographs supports this as Wittick spent a lot of time there as well as at his studio in Fort Wingate, New Mexico where other photos in the album are from. Given the handwritten caption on the Fort Wingate Officer photo, it could be surmised that an officer pictured, or one of their family members, created the album. The wrong date in the Fort Wingate caption could be attributed to the album being assembled years after the photos were taken.

After selling his Gallup studio in 1900, Wittick worked solely from his studio at Fort Wingate, traveling periodically to different reservations, until his death. He became quite a well-known figure around the fort, and it is possible the photos were all bought from his gallery there (Broder, 56-57). Even still, the assembly of the album remains mostly a mystery given the lack of information about the creator.

HOPI ALBUM

The album of the Hopi villages differs from the 1880s album for several reasons. Most obvious is the larger size. The Hopi album measures 22 by 27 ½ inches with each photo measuring 17 ¼ x 21 ⅜ inches. The photographs are housed in a circa 1940s green cloth binding with guilt lettering on the spine that has been partially rubbed off. The acquisition record from Mudd Library suggests the title is “South. Portion of Rocky Mountain System in U.S. Photo Views of Ancient Ruins.”

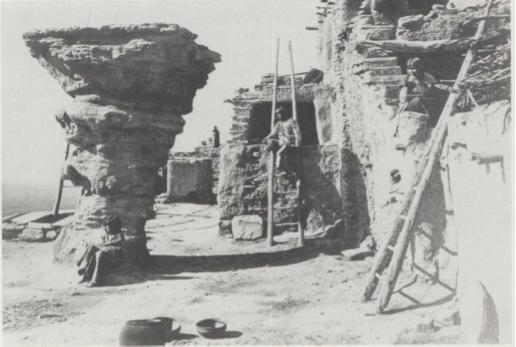

The album includes photos from three Hopi villages: Walpi, Mishongnovi, and Shipaulovi (spelled in the album as Wol-pi, Mi-shong-i-ni-vi, and Shi-pau-i-lur-vi respectively). Walpi is identified with First Mesa whereas Mishongnovi and Shipaulovi are Second Mesa villages. [11]

There are 9 photographs in the album which mainly focus on the building structures, however, there are several people and animals included in some of the photographs. Given the positioning of the figures, and their inherent stillness (as the wet plate photographs required still subjects), they most likely posed for the photos.

Despite the photos seemingly portraying the mundane life in the Hopi villages, with photos of the terraced houses and the court included, the posed nature of the figures betrays the process and purposefulness required to take photographs in the late 19th century.

It is significant to note that the Hopi refused to pose for Wittick’s style of staged portraits with props. Despite his close relationship with many Hopi people that granted him inside access to ceremonies and rituals, his only portraits of Hopi subjects are of young girls in traditional Hopi dress like the one included in the 1880s album.

Noticeably missing from the photos are the often-inaccurate costumes and props Wittick would have other subjects don. [12] Given the reluctance of Hopi people to participate in Wittick’s staged portraits, his photos of Hopi villages are confined to those of buildings, street scenes, etc.

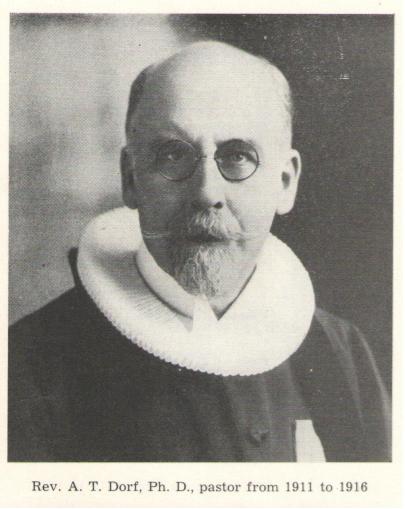

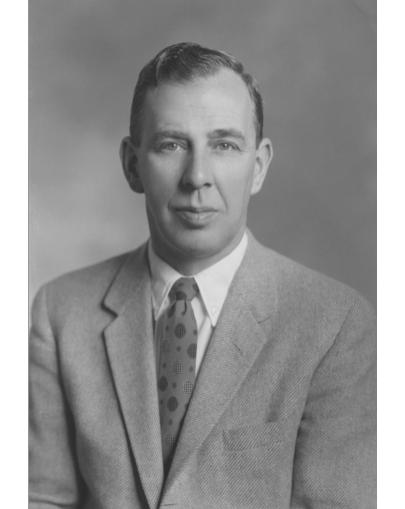

The early provenance of the photographs is unknown, but they were gifted to Princeton by A.T. Dorf on November 28, 1941. Alfred Thorkil Dorf (pictured on the left) was a minister from Denmark who immigrated to the United States to run a small Danish Lutheran College in Nystad, Nebraska. [13] While no connection to Wittick or the West is clear in information about Alfred Dorf himself, the same cannot be said for his son Erling Dorf (pictured on the right).

Erling was a professor of Geology at Princeton with a keen interest in the Yellowstone region and the West. [14] It is unknown whether Alfred himself gifted the photos or if Erling did so in his father’s honor. It is also unknown whether the photos were bought from Wittick directly or if they went through many hands before ending up at Princeton.

The album’s captions are not printed on the photographs themselves and there are no visible markings on the negatives. The printing of the captions in ink on the album pages in unlike Wittick’s usual works. In comparing the captions to the hundreds of available photographs with captions written by Wittick it is also unlikely that Wittick wrote the captions himself as the spellings differ greatly from Wittick’s captions. For example, in the album Walpi village is spelled “Wol-pi” whereas Wittick almost always spelled it “Hualpi.” [15] While the absence of Wittick’s name on the negative calls the identity of the photographer into question, it could be due to the nature of the photos belonging in a cohesive album instead of loose photographs that were often sold individually and thus needed individual signatures. [16]

The exact photos could not be located anywhere in extensive searches for them. However, similar photographs of the same scenes were found and identified as Wittick photos which supports the idea that the photos in the album are in fact his. The third photograph of the album, titled “Wol-pi,” features an almost identical scene to another photograph that is part of a private collection and included in Broder’s book, Shadows on Glass. While the photo in the album has two visible figures, the photo from the private collection is absent of any people. A similar negative negative in the Palace of Governors collection in a different size suggests a third version of Wittick’s view of Walpi. Also included in Broder’s book is another very similar photograph from a private collection.

The similarities between the photos could be evidence that Wittick photographed the exact same scenes on different occasions and for different purposes. If he was compiling 9 photographs for a cohesive album, he could have revisited all his favorite views he has previously taken photographs of. Although the photos from the book are dated around 1890, there is no conclusive evidence that the album was created before or after the other, almost identical photographs.

Given the difficult conditions in which Wittick often worked while on the road away from his studio, he often had a pack mule which carried his camera, tripod, and heavy glass plates, it is not unreasonable to assume that he was somewhat reliant on these specific views due to road access or rough terrain that would make alternative shots unfeasible. [17]

The photos of the Hopi mesas seem more concerned with the landscape and architectural strengths of the Hopi villages, unlike many of Wittick’s other photographs which prioritize the views of individuals and cultural gatherings. The choice to exclude any of Wittick’s most famous photographs like those of the Snake Dance further supports the idea that the photos were taken in succession and for the specific purpose of being packaged together as views of the Hopi villages. The connection to Erling Dorf as a geologist could speak to his, or his fathers, interest in the land and structures over the cultural events and people from these places.

Conclusion

Ben Wittick’s photos are significant in their individual impact as well as in the greater milieu of white photography of Native communities in the late 19th century. These two albums are an excellent example of the differences in composition an album can take on, even if the subjects are similar and the photographer is the same, as the significance of the assemblage of the album and motivations of the creator are magnified by the stark juxtaposition.

This essay has just begun to unravel the stories behind the photographs and the albums as they exist today. Many questions remain unanswered. How was the 1880s album compiled? And by who? Who was the audience for many of Wittick’s photographs? How has the meaning of the photographs changed from when they were originally taken? What is the value in contextualizing Wittick’s body of work? How does he fit into the greater story of photography at the time?

These questions still do not realize the full significance of these albums and the full scope of inquiry that could be applied to further research. The albums are unique in that they exist at all. Very few Ben Wittick albums are available. The University of New Mexico, which has by far the largest collection of Ben Wittick material, houses only 7 albums. Wittick’s photographs remain valuable sites of research for both their content and their life as primary sources over 100 years later which is just the beginning of the discussion of these albums' value to Princeton’s collection as well as the greater academic discourse on photography of, and not for, Native communities.

The album's have significant value in their ability to contrast each other and speak to wider themes of white photographers on Native reservations. But, most importantly to remember, is the people and places that these photographs represent and the mystery behind the stories that are held in the pages that have not yet been uncovered.

[1] Patricia Janis Broder, Shadows On Glass: The Indian World of Ben Wittick, (Savage, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1989), 36.

[2] Broder, 38.

[3] “Photographs by Ben Wittick,” Centennial Museum, The University of Texas at El Paso, http://museum2.utep.edu/LL/wittick_LL.htm.

[4] Broder, 23.

[5] Broder, 50.

[6] Broder, 35.

[7] Broder, 42.

[8] Arthur Olivas and Ben Wittick, Wittick Collection, Volume 1 (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico, 1971), Foreword.

[9] George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy At West Point, N.Y.: From Its Establishment, In 1802, to 1890, with the Early History of the United States Military Academy, 3rd ed. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1891.)

[10] Charles Collins, “ON THE MARCH WITH MAJOR TUPPER’S COMMAND: John F. Finerty Reports the Cibecue Campaign of 1881,” The Journal of Arizona History 40, no. 3 (1999): 254.

[11] Lomawywesa (Michael Kabotie), “Hopi Mesas and Migrations: Land and People,” In HOPI NATION: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2008, 45-52.

[12] Broder, 46.

[13] Sheldon Judson, “Memorial to Erling Dorf: 1905-1984,” The Geological Society of America (1984): 1-3.

[14] Judson, 1.

[15] This is currently the commonly accepted spelling.

[16] The acquisition of the photos into Princeton’s library came before Special Collections and so the original cataloging was impossible to locate. It is unclear whether they were originally classified as Wittick photos or if that identification was made later.

[17] Gar Packard and Maggy Packard, Southwest 1880 with Ben Wittick, pioneer photographer of Indian and frontier life, (Santa Fe, N.M.: Packard Publications, 1970), 3.