Press Under Imprisonment: Uses and Abuses of Publications in Japanese Internment Camps

By: Evan Brandon '23

We wish to thank those who by generously giving their time and effort made the publication of this little booklet possible.

In 1942, shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Executive Order 9066, resulting in the incarceration of 127,000 Japanese Americans. Individuals with any degree of Japanese descent, from Issei (first-generation Japanese American immigrants), to Nisei (second-generation Japanese) Americans, to even Sansei (third-generation Japanese) Americans citizens, faced internment.

The Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) quickly built temporary camps called assembly centers, which stood as placeholders until other, more permanent camps were built. In the Spring of 1943 the WCCA dissolved to become the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which governed these ten, more permanent concentration camps, known as “relocation centers,” located throughout the American West.[1]

Despite the fact that Japanese Americans were forced to abandon their homes, inmates nevertheless tried to maintain some semblance of normalcy during their time in the camps. One way they accomplished this was through camp publication efforts. Princeton’s Western Americana collection has recently acquired a few of these internment-era publications. While these acquisitions only scratch the surface of the plethora of publications produced in these camps, the assortment nevertheless captures the variety in both subject-matter and intended audience of these printed works. The publications range from individual issues of regularly published camp newsletters, to less frequently printed works documenting camp development, to a program for an intramural Young Buddhist Association conference.

All of these items individually carry deep and storied histories that cannot be discussed in-depth here. Taken together, however, a larger story of camp publications emerges that elucidates the nature of their production and use by inmates. A central question to be asked about these publications is: how “free” were these centers’ presses? While publications were an outlet for normalcy within these camps, they nevertheless faced varying degrees of censorship by camp administration. Such censorship, therefore, emphasizes yet another way in which the liberty of these inmates was severely limited during this sad chapter of American history.

“A Year at Gila” and “Second Year at Gila”

These two “anniversary booklets,” one a follow-up of the other, are perhaps the least personal of all of the publications under discussion. They provided not “news items that are of direct interest or concern the affairs of the evacuees” (a role which the camp’s tri-weekly publication fulfilled), but were intended to serve as a record of the “tangible evidences of purpose and effort – one year’s accomplishment to which residents can point to with pride.”[2]

Each of the two booklets, dated exactly one year apart (July 20, 1943 and 1944), is fully mimeographed and bound with staples (as all of the items under discussion are). The cover of “A Year at Gila” bears an illustration of the camp from an aerial viewpoint, and the cover of “Second Year at Gila” is less decorated, featuring only an illustration of the title surrounded by a design of red, tendril-like lines with blue and red dots running up the side of the page.

“A Year at Gila,” which describes essentially the first year of the camp’s operation, feels largely disconnected from the personal experiences of the inmates. Although there is an acknowledgement on the final page of "those who by generously giving their time and effort made the publication of this little booklet possible," names of individuals are seldom mentioned throughout this first book, save for an address at the beginning by project director, Leroy H. Bennett.[3]

“Second Year at Gila” takes steps to alleviate this impersonality, including a section titled, “Takes on Individuality,” which discusses the “red topped and white walled barracks” that have “taken on an individuality that breaks the monotony of sameness.”[4] The piece intends to show that, after a year in the camp, the inmates had settled into and individualized their now familiar residences. The irony, however, of reducing the unique humanity of the inmates to variation among the buildings they inhabit appears to be lost to the writer. Nonetheless, names of a few inmates found a place at the back of this second booklet in a section devoted to chronicling significant moments in the center throughout the year.

The barracks are still red topped and white walled. But each has taken on an individuality that breaks the monotony of sameness.

Both works feature many illustrations throughout, though no artists are credited, save for a foldout illustrated scene in the first booklet, signed “KIRA.” This image depicts a road running through the camp, with a woman walking alongside a truck, and three male figures gathered beside some crates. The piece presents a mundane view of camp life, contributing to the message that runs throughout both booklets: life within the camp was, in many ways, similar to life outside.

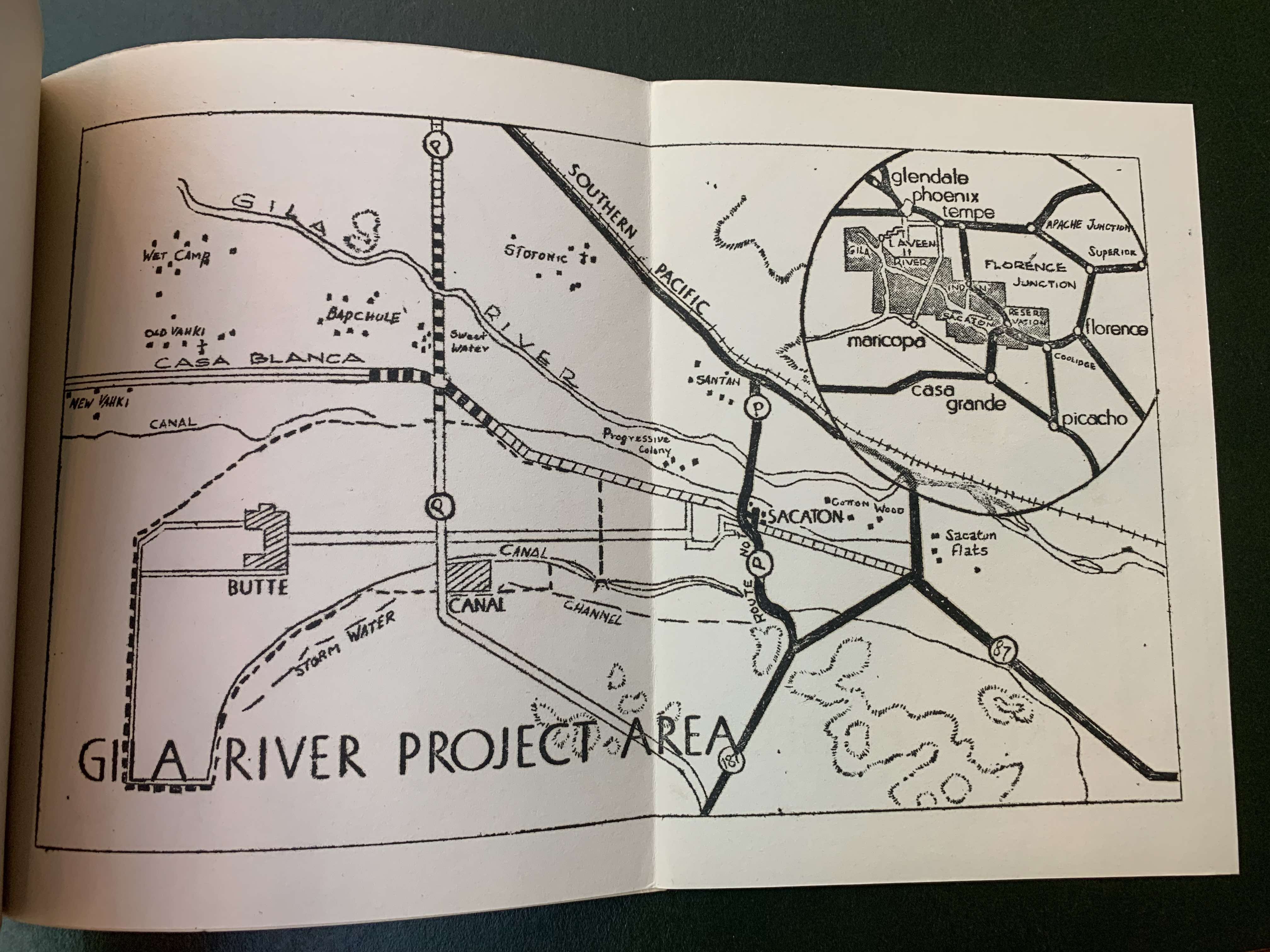

Adding to their impersonal character, the booklets betray very little information about their own creation. At the very least, we do get the precise location of these printed works, as the second booklet tells us on the inside cover that it was “published by the Gila News-Courier / 57 News Building, Rivers, Arizona,” a building which can be identified on the foldout map of the project area in the first book.

This foldout map indicates that Gila was divided into two camps, Canal and Butte, with the publication building positioned in Camp Butte in the northeastern cluster of buildings. The Gila News-Courier building produced a tri-weekly news publication bearing the same name, with “an average circulation of 4,000 copies and… staffed by a personnel of about twenty-eight.”[5] As evidenced by these very booklets, the News-Courier was responsible for the publication of works for all divisions within the camp, save for official WRA documents, illustrating the significant role that publication departments played in facilitating camp-life.[6]

Tule Lake’s Young Buddhist Association Conference Program

Shifting now to arguably the most personal of these items, this booklet details the schedule and relevant materials for the annual, intramural Young Buddhist Association Conference, held from June 11-13, 1943, at Tule Lake camp in California. The booklet, like the Gila publications, illustrates how the publishing efforts in these centers were intimately involved in other facets of camp life in addition to providing day-to-day news.

According to Lauren Kessler, the Tule Lake camp was “riddled by strikes, demonstrations, and bloodshed, [and] became a maximum security facility in the summer of 1943, housing what the WRA thought of as troublemakers.”[7] This discord and strife within the camp are reflected in the quality of the camp’s publications, as they were “perhaps the least ambitious and most amateur of all internment camp newspapers.”[8]

While this particular item exhibits some of these qualities, clearly there was some care put into its creation. The booklet itself is held together by a single staple at the midpoint of the left edge. The cover is made of dark-blue paper whose grain is similar to construction paper, a design choice that makes the black print somewhat difficult to read. It bears the heading, “The Annual Tule Lake Young Buddhists Assn. Conference,” and is adorned with an illustration depicting several people entering a building whose windows illuminate the street outside. For some reason, a trapezoid is drawn that frames nearly the entire illustration, perhaps an artifact of the artist’s reference for perspective.

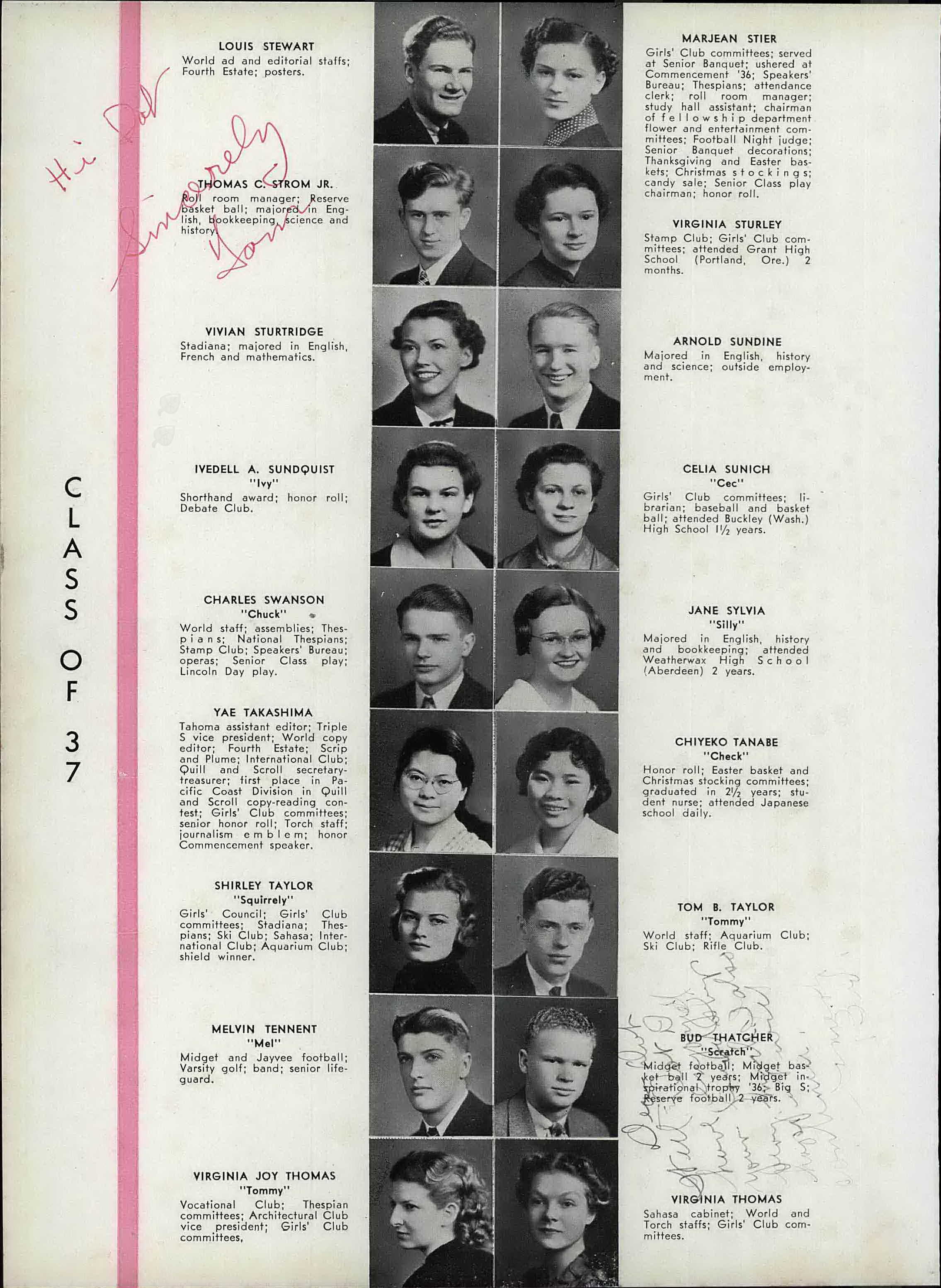

The most intricate component of this item is the rosette ribbon that is fixed to the cover by a pin. The ribbon is made of multiple pieces of colored paper and a thread tassel, all of which are held together by a single staple. One of the ribbon’s streamers reads “YBA,” and on the button is an identification card headed “UNITY THRU GASSHO.”[9] The name of the program’s owner, Chiyeko Tanabe, is handwritten on this card as well as at the top of the cover (which also gives her hometown of Tacoma, Washington).

Ms. Tanabe was born on December 9, 1918, in Seattle Washington. At Stadium High School in Tacoma she was on the honor role, graduating in 1937 after only two and a half years.[10]

She arrived at Tule Lake on July 24, 1943, from Pinedale Assembly Center. She stayed until September 19, 1943, at which point she was transferred to Granada and eventually to Heart Mountain. Finally, on April 17, 1945 she gained her freedom.[11] She eventually found her way back to Washington, living in Tacoma as a typist.[12] She must have maintained her Buddhist faith after evacuation, as she was married in a Buddhist church to Frank Masatoshi Hisayasu on August 8, 1954.[13] She died on January 6, 2000.[14]

The lower quality of the Tule Lake publications compared with productions in other camps is evident. Even so, we can see the role that camp publications played in providing the inmates with some semblance of normalcy. Within the booklet are various welcome addresses by YBA leaders – and even the center’s project director himself – celebrating the opportunity to come together to observe their faith. The book also includes lyrics to several songs so that all attendees might join in the music together. The last pages of the booklet are reserved for signatures of other attendees of the conference, serving as a testament to camp publications’ capacity to forge lasting human connections among Japanese internees, despite the hardships that they faced.

To that end, this printed work, unlike others in this collection, is uniquely anchored to a particular moment within the camp, produced to be used chiefly by those individuals present at the YBA conference: the item was made to be utilized in time by the attendees of the event it supplements. The extent to which this item looks through time, however, is still undoubtedly personal. While the signatures in the back of the book may be interesting avenues of historical enquiry to researchers, they carry singular significance to the booklet’s owner, Chiyeko Tanabe. Although the moment of the conference has passed, the signatures -- and the booklet itself -- act as a means for personal reflection on the intimate connections fostered throughout Ms. Tanabe’s own unique experience living in the camp. For more on how these relationships lasted even beyond the inmates' time in the camp, see Julia Chaffers' article on internment camp yearbooks, linked here [insert link here to her publication].

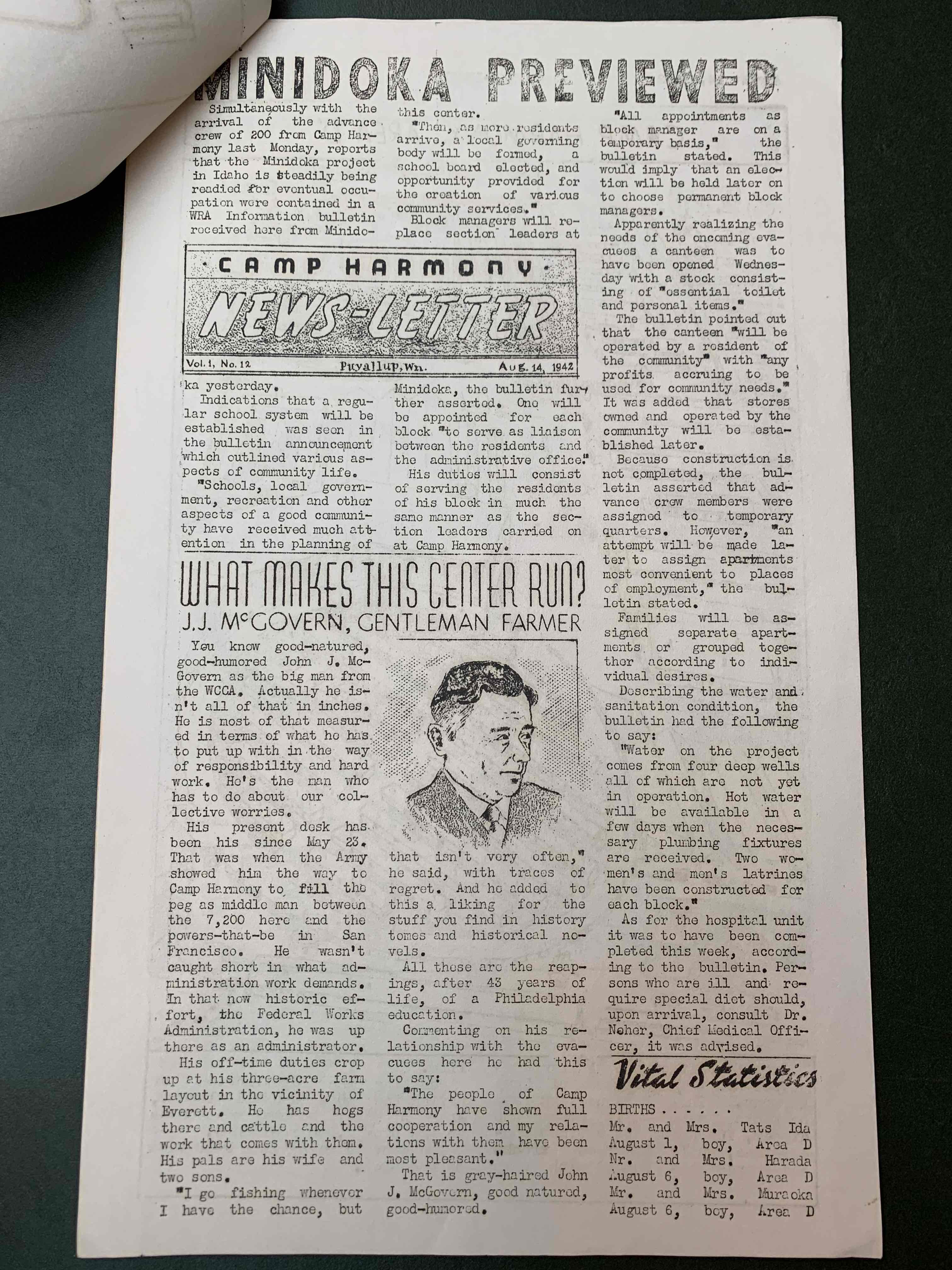

Santa Anita’s Pacemaker and Jerome’s Denson Magnet

These two publications come from separate centers, but they highlight the differences in censorship practices between the earlier assembly centers and the more permanent relocation centers. According to Takeya Mizuno, the news publications of the WCCA-controlled assembly centers (including Santa Anita’s Pacemaker) were heavily censored, a practice that evolved after the shift to WRA-run relocation centers.[15] Mizuno argues that “the WRA adopted a comparatively more moderate ‘supervisory’ policy, putting evacuee newspapers under ‘supervision’ instead of full, rigid ‘censorship.’”[16] This subtle variation in censorship practice is evident in these publications. While none of the Pacemaker’s stories presents the center in a bad light, Jerome’s Magnet manages to highlight at least some negative aspects of camp life.

The Pacemaker was a publication produced in the Santa Anita assembly center, which was open from March to October of 1942. Unlike the Gila publications, this local publication focused on reporting the day-to-day, newsworthy events to the center’s inmates. This particular issue, Volume 1, No. 11, was issued May 26, 1942, and consists of four pages. The paper itself is not bound, held together by a single staple, but it’s unclear if this was how the paper was originally distributed. There is little illustrated material in the newsletter, as space on the page is almost entirely taken up by text, printed in three columns.

The paper’s stories express little to no negativity towards camp-life or the administration, with perhaps the only pessimistic stories being an announcement of a mother’s death from an undisclosed illness, and report of a brief blackout in the camp.[17] This absence of critical or even discussion-worthy material supports Mizuno’s argument that “the newspaper served instead as the camp administration’s mouthpiece.”[18] Even Eddie Shimano, the head editor of the Pacemaker, affirmed that “the paper acts mostly as an official information bulletin, dressed up in newsy, attractive, readable style, of administrative orders.”[19]

A box on page two indicates that the newsletter was published every Tuesday and Friday free of charge, and contains the names of the editorial staff and the address of the editorial office. One story celebrates the first-place prize won by the Pacemaker’s own Women’s Editor, Asami “Sammy” Kawachi, in an essay contest sponsored by the Common Council for American Unity.[20] The essay, “Strangers’ Rice,” can be found in the Summer, 1942, issue of Common Ground, a publication for which Eddie Shimano would work following his evacuation (freedom from incarceration).[21]

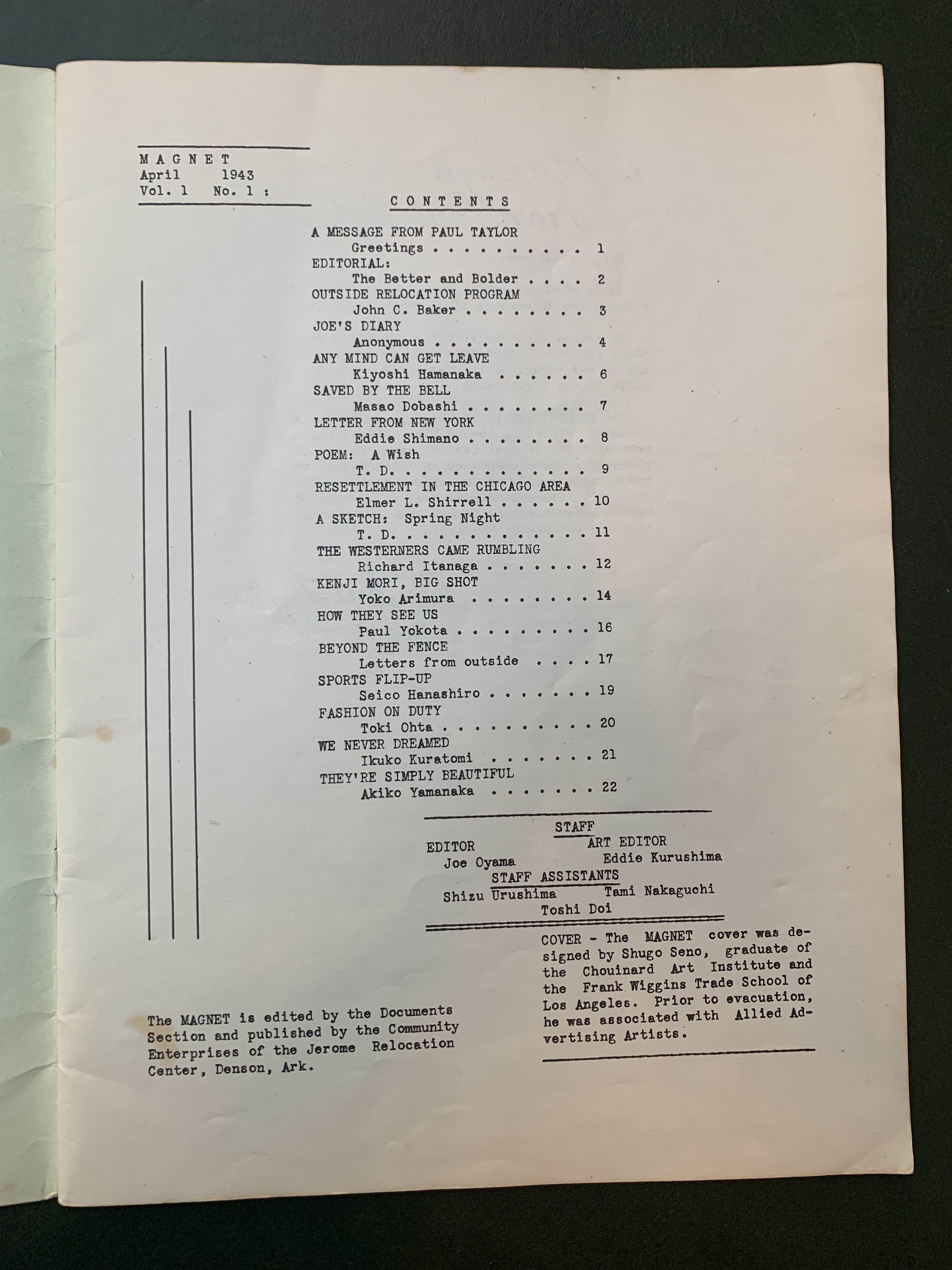

By contrast, the Denson Magnet of the Jerome relocation center does not exhibit the same degree of censorship as Santa Anita’s Pacemaker. The magazine, published in 1943, is well-made, with the staples that bind the book together fixed directly in line with the middle crease. The cover, designed by Shugo Seno, features an aerial illustration of a section of the camp with a giant horseshoe magnet facing towards the ground from high above. Below the title of the publication reads the issue’s price, ten cents per copy, and at the bottom of the cover reads the April publication date.

This was evidently the first and only issue to be published, which is ironic given the mission of the magazine stated by camp director Paul A. Taylor: to provide “a better understanding between the administration and the Center population.”[22] Jerome did have another bi-weekly newsletter, however, called the Denson Communique, of which Eddie Shimano (mentioned above) was the head editor.[23] Each section of the Magnet is accompanied by detailed illustrations relevant to the contents of the story. Towards the back of the magazine is a hand-drawn pictorial map of Arkansas followed by a section of cartoons caricaturing camp life.

The Denson Magnet captures the less restrictive form of censorship that characterizes the publications of the later, WRA-controlled relocation centers. The magazine presents some criticism of camp life, though there is little discussion of more serious administrative or structural problems that were present in the camp. For example, tension over labor conditions in the camp’s lumber industry eventually led to a strike, and by November of 1943, seven months after the publication of the Magnet, Taylor would resign from his position as project director in the wake of the controversy.[24]

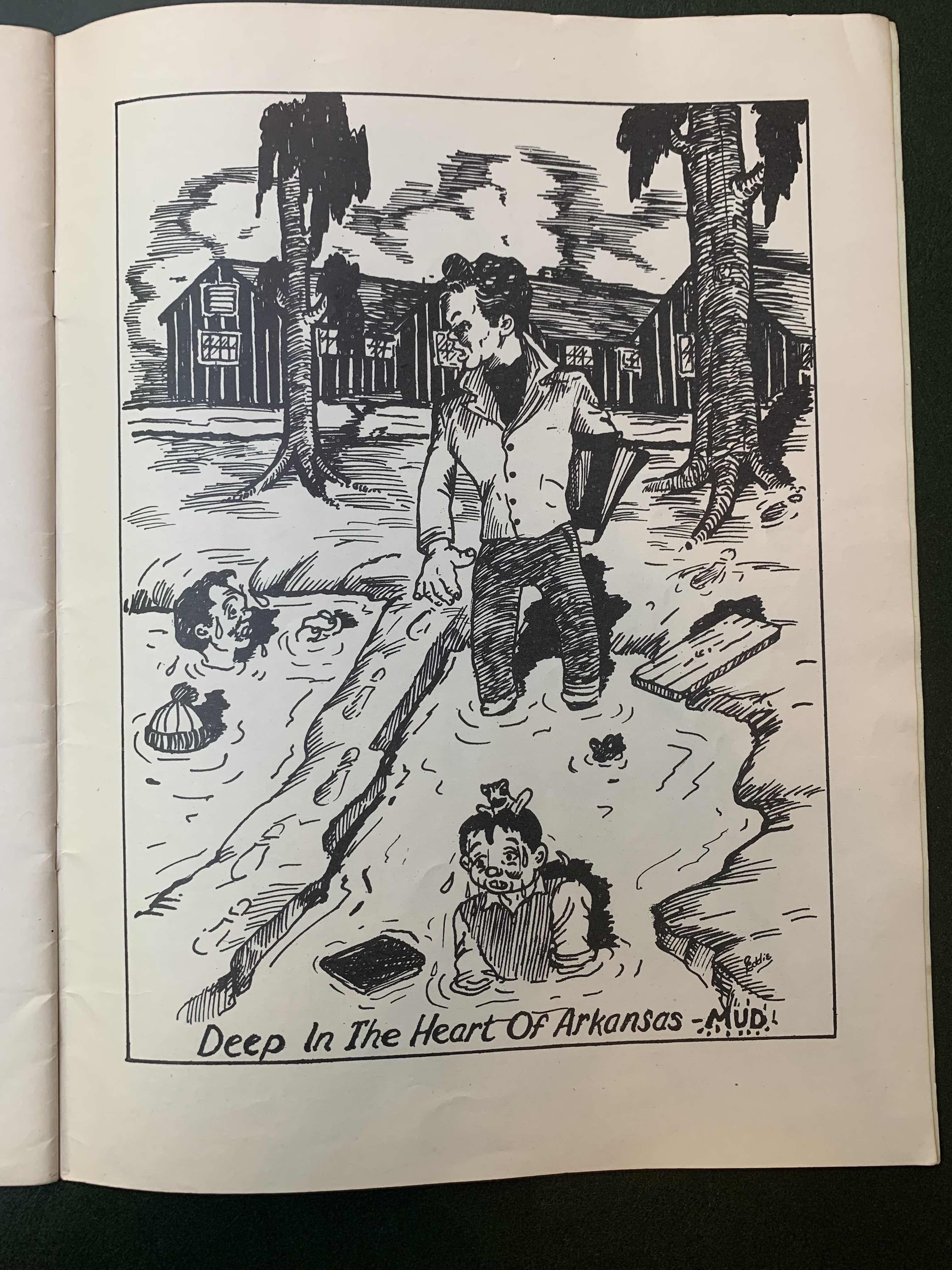

Instead, the magazine left room for the airing of mild, superficial grievances, including repeated references to the camp’s over-abundance of mud due to Arkansas’ rainy climate.

One cartoon at the back of the magazine pictures three young boys in a mud puddle. The largest, angry-looking boy, perhaps a school bully, stands over the other two who have evidently fallen into the mire, one of whom is depicted with a frog on his head. The caption at the bottom reads, “Deep In The Heart Of Arkansas – MUD.”

Then came the downpour. Having only ordinary shoes, one couldn't possibly go outdoors. Even with galoshes or boots, one would lose them in the mud.

Ikuko Kuratomi echoes this sentiment, commenting on the practical and aesthetic problems that mud caused. She writes, “then came the downpour… Even with galoshes or boots, one would lose them in the mud.” In the winter, Kuratomi recalls awaking “one morning to see outside a beautiful winter picture,” a picture that would only last so long, as “the form of the ground changed from ice to slush to mud.”[25]

Even Eddie Shimano, who contributed to the publication a letter from New York after his evacuation, comments on the mud in his piece: “walking on sidewalks – no mud, mind you, no mud – is so pleasant that I’ve overdone it in the past month. The payment [sic], however, no matter how much better than mud, is still not very soothing on the bare sole.”[26] But this mild, almost affectionate criticism towards camp life certainly does not represent all that the inmates would have wanted to say. Eddie Shimano aired some of these sincere grievances just a few months later in the 1943 Summer issue of Common Ground, a magazine centered around promoting racial equality and multiculturalism, arguing that life in the concentration camps had essentially undermined and perverted the traditional structure of the Japanese family.

A Jap's a Jap. It doesn't matter whether he's an American citizen or not.

The two articles also present conflicting messages about Shimano’s own racialization. In the Magnet, he indicates in that he has “yet to experience a single incident of any unpleasantness over [his] racial background,” noting he shared drinks and sang with White men on his train ride to St. Louis.[27] But he does not hesitate to condemn the racist underpinnings of internment in his Common Ground piece. He writes, “the recent statement of Lieut. Gen. John L. DeWitt, ‘A Jap's a Jap. It doesn't matter whether he's an American citizen or not,’ serves only as added proof that military necessity was a convenient, if true, excuse for an anti-Japanese pogrom.”[28] Now liberated from the looming presence of the WRA over the editorial staff, Shimano freely describes “the nightmare of demoralization and despair that is a relocation center.”[29]

Conclusion

Through this small assortment of camp publications, a picture of the larger role of camp publications – regarding the experience of both the editorial staff and readers themselves – begins to develop. Gila’s anniversary booklets and the Tule Lake conference program demonstrate the variety of material produced in these camps: the publishing departments of these centers were producing more than just news, but printed materials for a multitude of occasions.

By the same token, the various purposes for which these publications were created present contrasting perspectives of the humanity of the internees who read them. On the one hand, Gila’s anniversary booklets generally depersonalize the inmates. On the other hand, the Tule Lake program shows the extent to which publications served as a conduit for normalcy in the lives of inmates and facilitated the generation of relationships among like-minded individuals.

On the editorial side, by tracking Eddie Shimano’s presence within the Pacemaker, Magnet, and Common Ground, we also see the varying degree to which these materials were monitored and censored by camp administrations. That the Denson Magnet was (slightly) more critical of camp life than Santa Anita’s Pacemaker reflects Mizuno’s claims that the administrations of the WCCA’s assembly centers imposed a stricter form of censorship than did those of the WRA’s relocation centers. Nevertheless, only by being liberated from internment and returning to society at large could the inmates who contributed to the creation of these publications truly enjoy a free press.

[1] The term “concentration camp” carries particularly charged connotations since the horrors of the Holocaust. Some scholars use more neutral language in order to avoid confusion and controversy, while others freely use the term to argue that the official name, “relocation center,” is a euphemistic misrepresentation of what the camps actually stood for. Eddie Shimano, an editor and contributor to some of the publications discussed below, describes the assemblage of himself and other Japanese citizens to these centers as a “concentration” in a piece for Common Ground published after his evacuation (discussed below). I use the term here at once as Shimano uses it (i.e., as a reference to the literal gathering of inmates into enclosed areas), but also thoughtfully aware of the severe baggage that the word carries. In doing so, my goal is not to diminish the atrocities faced by Jewish people throughout World War II, but to acknowledge the misdeeds committed by the U.S. government at this contemporaneous moment in history. See Takeya Mizuno, “The Creation of the ‘Free’ Press in Japanese-American Camps: The War Relocation Authority’s Planning and Making of the Camp Newspaper Policy,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78, no. 3 (September 1, 2001), 515; Raymond Y Okamura, “The American Concentration Camps: A Cover-Up Through Euphemistic Terminology,” The Journal of Ethnic Studies 10, no. 3 (Fall 1982): 95-109.

[2] “A Year at Gila,” [6, 27].

[3] ibid., [2, 44].

[4] “A Second Year at Gila,” 3.

[5] “A Year at Gila,” [27].

[6] For more on the Gila News-Courier, see Patricia Wakida, “Gila News-Courier (newspaper),” Densho Encyclopedia, May 12, 2014. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/GilaNews-Courier(newspaper)/; "Gila River: A History of Relocation at the Gila River Relocation Center," The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1945. Part IV, Chapter Six. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt8j49n9pt;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=d0e1886&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e1886&brand=oac4.

[7] Lauren Kessler, “Fettered Freedoms: The Journalism of World War II Japanese Internment Camps,” Journalism History 15, no. 2–3 (July 1, 1988), 76.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Gasshō is a greeting gesture used in various Buddhist traditions, whereby the palms are placed together with fingers pointed upward.

[10] “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999,” digital image s.v. “Chiyeko Tanabe,” AncestryLibrary.com. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/268523080:1265.

[11] “Final accountability rosters of evacuees at relocation centers, 1944–1946,” Microfilm publication M1965, 10 rolls. Records of the War Relocation Authority, Record Group 210. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/108612:2982, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/111071:2982, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/75789:2982; Japanese-American Internee Data File, 1942-1946, Record Group 210, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/62120:8918.

[12] U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995, AncestryLibrary.com. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/782369641:2469.

[13] Washington Marriage Records, 1854-2013, Washington State Archives, Olympia, Washington. https://search.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=2378&h=3755517&tid=&pid=&queryId=07f3707003398b4a3be8763a53962967&usePUB=true&phsrc=SBt126&phstart=successSource; “Tacoma News,” The Northwest Times, August 25, 1954. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86071999/1954-08-25/ed-1/seq-3/.

[14] U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, AncestryLibrary.com. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/42169711:60901.

[15] Takeya Mizuno, “Journalism Under Military Guards and Searchlights,” Journalism History 29, no. 3 (October 1, 2003), 101.

[16] Ibid., 105; For more on the extent of this “supervision,” see Takeya Mizuno, “The Creation of the ‘Free’ Press in Japanese-American Camps: The War Relocation Authority’s Planning and Making of the Camp Newspaper Policy,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78, no. 3 (September 1, 2001), 503–18.

[17] “Mother Dies of Illness,” Pacemaker, May 26, 1942, 2; "Blackout Effective," ibid., 1.

[18] Mizuno 2003, 102.

[19] Cited in Mizuno 2003, 102; this statement was written to Bradford Smith, Assistant Chief of the Foreign Language Division at the Office of Facts and Figures, on May 1, 1942.

[20] "'Common Ground' Awards $50 Prize To Womens Editor," Pacemaker, May 26, 1942, 2.

[21] See Asami Kawachi, “Strangers’ Rice,” Common Ground, Summer 1942; Kawachi’s essay details her life and career as up until internment. A Nisei herself, she bemoans the injustices that her fellow “Nisei who have and know only this as our country” (76) have had to endure.

[22] Heather Hathaway, That Damned Fence: The Literature of the Japanese American Prison Camps (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), 172; “A Message from Paul Taylor” Denson Magnet, April 1943, 1; Project director Paul A. Taylor bears no relation to Paul S. Taylor, the economist, husband of photographer Dorothea Lange, and staunch opponent of Japanese internment.

[23] Greg Robinson, “Eddie Shimano,” Densho Encyclopedia, August 11, 2015. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Eddie_Shimano/; Robinson also writes that after Shimano’s evacuation, his position was filled by Paul Yokota (who also contributed to the Magnet), and the name of the Denson Communique was changed to the Denson Tribune.

[24] Hathaway 2022, 177-8.

[25] Kuratomi, Ikuko, “We Never Dreamed,” Denson Magnet, April 1943, 21.

[26] Shimano, Eddie, “Letter from New York,” Denson Magnet, April 1943, 8; likely, “pavement.”

[27] Ibid., 8-9.

[28] Eddie Shimano, “Democracy Begins at Home,” Common Ground, Summer 1943, 83.

[29] ibid., 79