On the Resort Frontier: The Bass Family Takes Colorado Springs

By: Connor McGoldrick '21

Access the digitized photo album via Princeton University Library.

When Frances Metcalfe Bass first arrived in Colorado Springs, her spirits were low. By the time she had made it to the Cheyenne train station in the final days of 1876, she had already run out of nourishment for her young child. On her way from Cheyenne to meet her husband at the time, Lyman K. Bass, Frances was further alarmed to witness her fellow train passengers shooting away at an antelope herd as they crossed the train tracks. When she finally was met by Lyman in Denver, it was certain she was having second thoughts on leaving her life of comfort and affluence in New York to make a new home in the rough-and-ready territory of the old American West. Though she did not know this at the time, Frances Metcalfe Bass was at the beginning of a years-long adventure that would place her at the forefront of the development of Colorado Springs and the greater Western-American region. These cherished memories of Frances and Lyman were captured and reproduced in this album, and represent an unforgettable experience for the Bass family that ended up being the main focus of Frances’ 1932 autobiography, entitled Heritage of Years: Kaleidoscopic Memories.[1]

Frances published the memoir the year before she died, and by then much had changed since those halcyon days in Colorado. Lyman died in 1889 in New York, and about a year later Frances married another young politician, Edward Oliver Wolcott, who had worked in legal and political circles in Colorado during much of Lyman’s time there.[2] Until her death, Frances (now Frances Metcalfe Wolcott) would spend much of her time entertaining politicians and celebrities at her brother Frank’s estate in Buffalo, NY. At the Hillcrest Estate, now an event venue, Frances hosted the likes of Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and actress Ethel Barrymore.

Frances’ photo album, measuring 38 by 30 centimeters, does show signs of wear, perhaps evidence that it was used as a regular family keepsake: the spine is partially torn and much of the binding is frayed. But the 176 albumen print photographs inside are in mostly excellent condition, with only a few showing creases or wear from improper pasting. Some of the photographs take up entire pages, while others form scrapbook-like collages. Frances or another caretaker captioned most of the photographs, usually with place markers or brief descriptions like "Balancing Rock, estimated weight 300 tons." The album also contains a printed bookplate on the pastedown that Frances may have used to mark books in her personal library.

The catalyst for the Bass family’s move to Colorado Springs was the declining health of Frances’ first husband, Lyman Kidder Bass.[3] According to Frances, Lyman had “broken his health in his arduous work through the malarial summer weather” of 1875, while Lyman was serving in the U.S. House of Representatives. Lyman was well-respected figure, both in Washington at home in New York. He maintained a cordial relationship with then-president Ulysses S. Grant and knew Grover Cleveland as his close friend and business partner.[4] Bass himself was quite accomplished; he was the youngest member of Congress at the time he served, and had previous experience as the district attorney for Erie County.

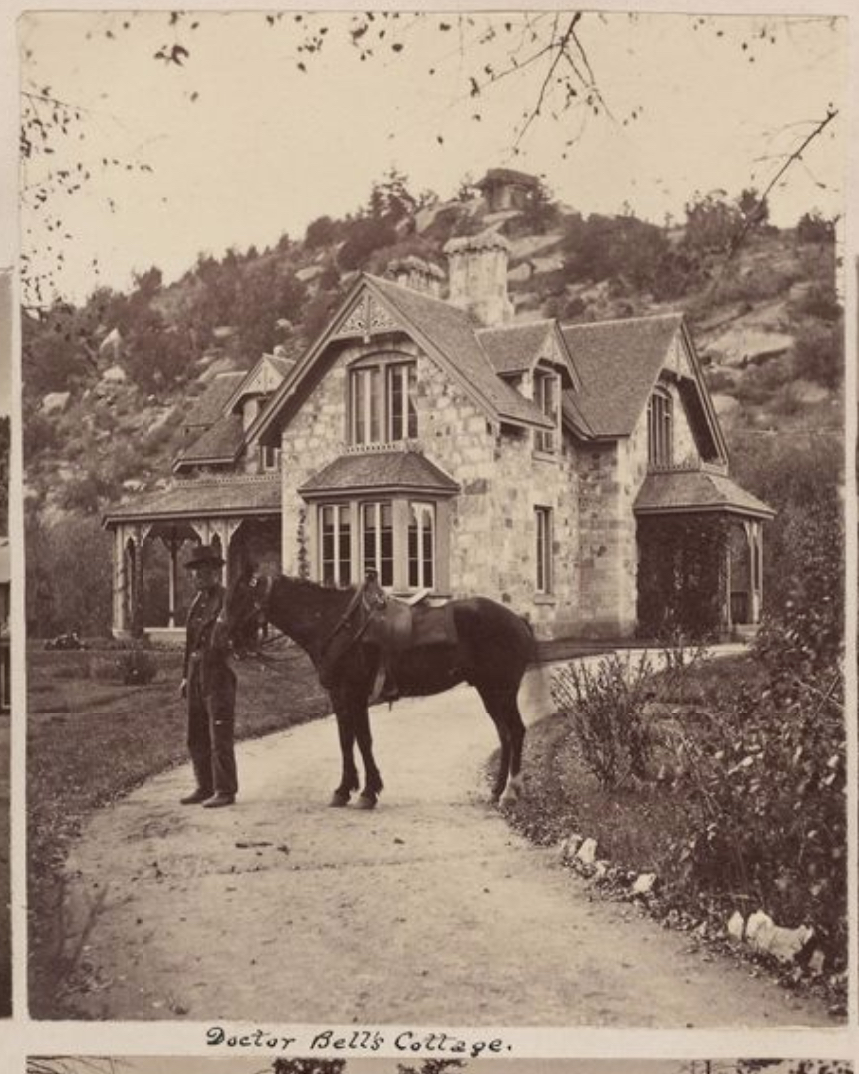

It therefore came as no surprise to Frances that Lyman, in escaping his obligations in Washington and taking time to rest, would become entangled in the work of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, whose owners also founded the city of Colorado Springs.[5] Shortly after Lyman arrived in the new city, he was goaded into joining the Denver & Rio Grande railroad in its fight to obtain the rights to construct “a railway through the Grand Canyon of the Arkansas River on the route from Denver to Leadville.”[6] After leaving for Manitou Springs in the summer of 1876, a sister town just west of Colorado Springs and home to the co-founder of the railroad and towns Dr. William A Bell, Lyman was so persuaded to assist Bell and his partner William Jackson Palmer in their railroad fight that he persuaded Frances to join him “as soon as [she] was strong enough to travel” after the birth of their son.[7] In the last days of December 1876, Frances left New York with her newborn son to join Lyman in the Pikes Peak region.[8]

Arriving in Colorado Springs from Denver on the “Narrow Gauge Railroad” built by Bell and Palmer, Lyman and Frances took a wagon in freezing weather for the last leg of their journey to Manitou Springs.[9] Arriving to Colorado with “terror at [her] heart,” Frances spent the following two days recovering from the physical and mental anguish of her journey. After she had recovered, their adventures in the Pikes Peak region commenced with a visit to the “Garden of the Gods”, inspiring such awe from Frances that she “laid [her] heart that day at the feet of the Sun God of Colorado."[10] It could be said that this represented her indoctrination into western life, as she referred to Pike’s peak by a translation of the native name for the peak as “Tava,” paying homage to “the way it collects and reflects the morning rays.”[11]

Judging from the pages of photographs dedicated to the Garden of the Gods and Pikes Peak, it is apparent that Frances became enraptured by the “enticing scenery” that served as one of the motivating factors for William Jackson Palmer to build settlements in this region. To use Frances’ words, when she arrived at the Garden of the Gods, feelings of “cold vanished, the glories of the mountain mesa and distant plain caught me by the throat.”[12] Entering on buggy through the narrow passageway that is the “Beautiful Gate”, they took in this 500 acre land area, surrounded by mountains and sandstone cliffs and filled with sandstone monuments.[13] Trading the worries that plagued her during her travels for the awe that the Garden of the Gods inspired, Frances Metcalfe Bass began to embrace and immerse herself in life on the Pikes Peak resort frontier. Many of these sandstone monuments are represented in her photo album. Much like Katharine Lee Bates found while sitting atop Pikes Peak writing “America the Beautiful,” Frances and Lyman were seduced into staying-a-while by the remarkable natural beauty of the region.

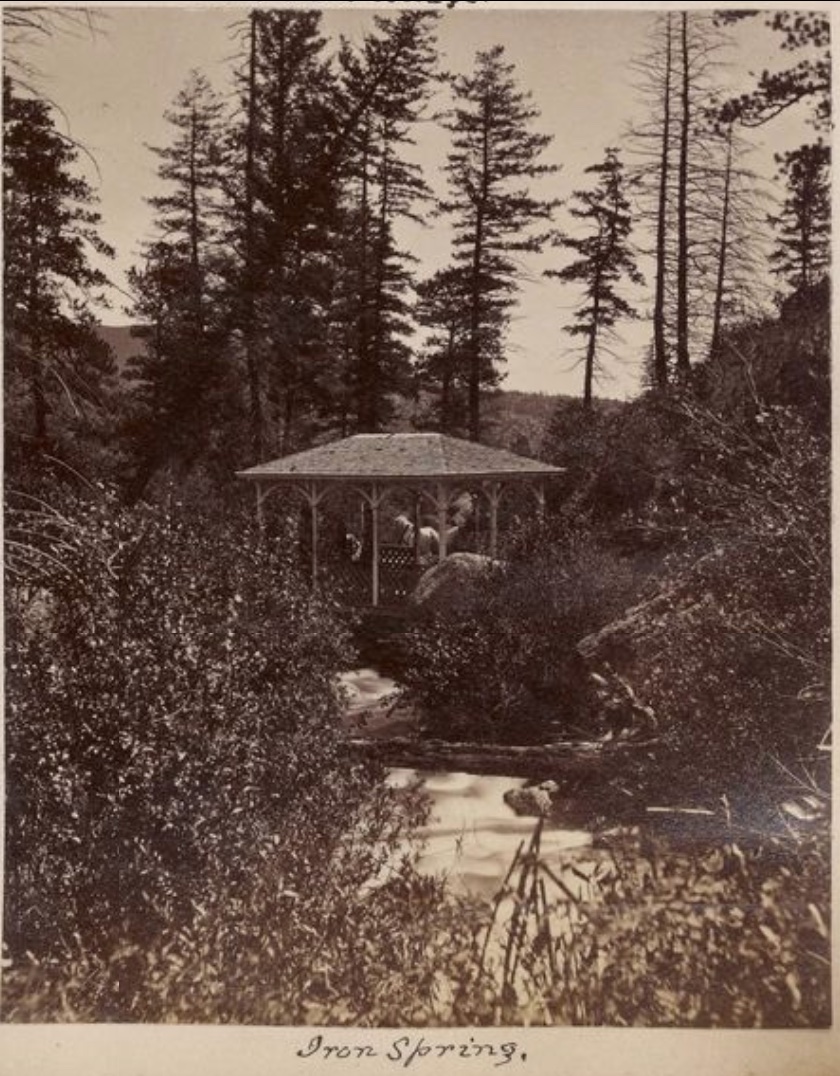

This sort of seduction into staying longer was typical of Colorado Springs and Manitou Springs, and was something that founder William Jackson Palmer both promoted and relied upon. Though Palmer and Bell’s initial motivation in creating a railroad that went from Denver to Colorado Springs may have been to efficiently send the resources gathered at the Pikes Peak mines, Palmer predicted after buying the land for Colorado Springs and Manitou Springs that the region would become a thriving resort town at the base of the mountain.[14] Palmer and Bell intended to attract visitors from the Eastern U.S. and Europe by promoting their town as a destination for rest and recovery due to its hot springs, agreeable weather, and picturesque scenery.[15]

In order to attract and accommodate “wealthy residents and capitalists, as well as intellectuals, artists, writers and inventors,” Palmer planted 10,000 trees in the city, “built lavish buildings with a European sense of style,” and laid out broad streets accommodating for future expansion. In fact, several of the streets depicted in this album still exist to this day. Palmer correctly believed that such practices would tempt investors from the East and Europe to settle in the region, with the Bass family being a prominent example of this. The resort town amenities and sophisticated architecture of the homes in the area were things that were certainly not lost on the Bass Family, as there are dozens of photographs in this album documenting these features.

After settling into their new home in Manitou Springs, a small place adjoined to the home of famous poet Helen Hunt Jackson, Lyman and Frances were asked to visit a ranch sixty miles from Manitou.[16] On this journey, Frances waxed poetic about “the lonesome herder of sheep, whose only loved companion was his faithful collie.”[17] She also noted, “as in the world of women, so among the ewes were good mothers and those who disowned their offspring, and some large-hearted ewe by a shepherd’s device suckled the deserted lamb.” Their time at the ranch met a grim end, however, as Lyman discovered that one of their escorts had committed suicide in response to not being needed for the return trip by his company.[18] This painful memory is not documented in the photographs, but speaks to the hardships of the West that even residents of resort towns could not avoid.

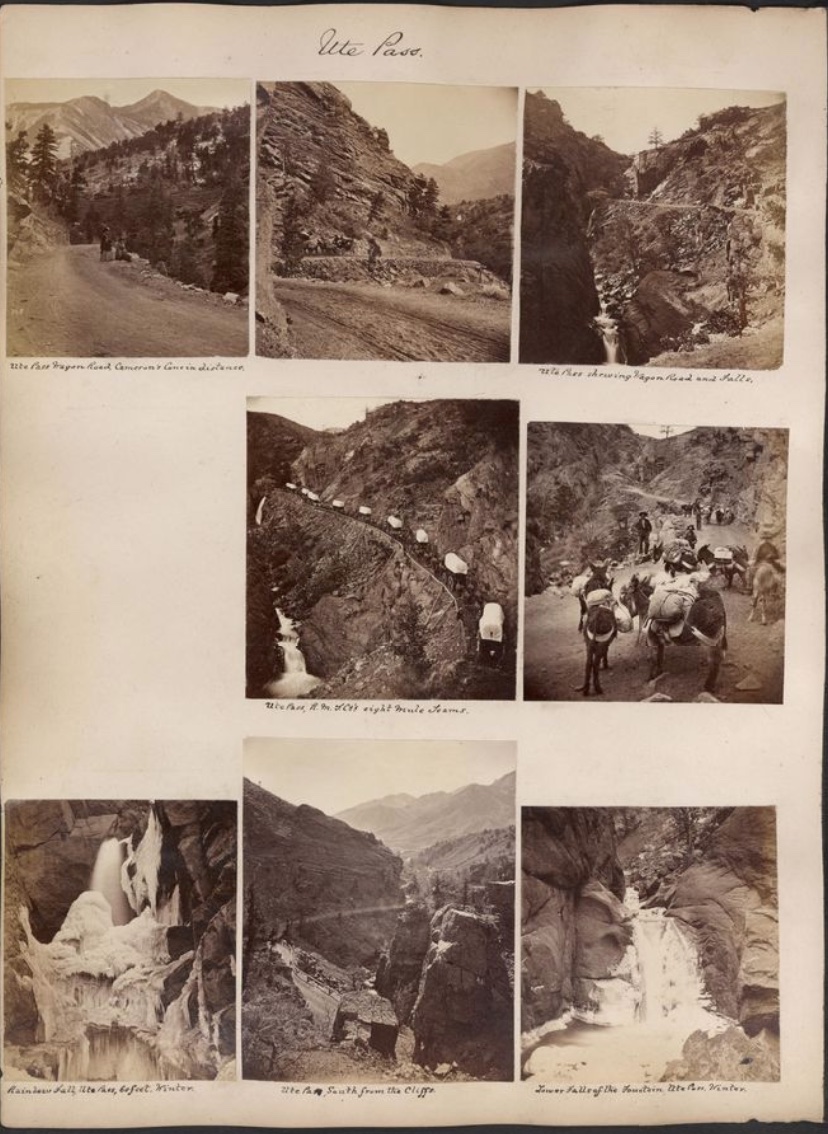

After the ranch visit, Frances and Lyman witnessed “the last visit of the Indians descending the Ute pass.” Though Frances does not include photos of this actual event in her album, she prominently features this route in her album and has specific photos of “the Fountain,” a stream along which these groups made camp. In her autobiography, she makes specific note of encountering a young native boy, “dancing an improvised war dance and brandishing a large knife.” Though this experience may have been alarming to Frances when she first arrived in the Pikes Peak region, she had been toughened by her experiences already to the point that such an encounter “brought no terror to our hearts.” Frances also observed a chief emerge from his teepee and “put his foot on the neck of one of his wives” to swing himself onto his horse, while additionally noting that “nothing unpleasant happened” in their passing through the area.

All of this traveling served to deplete the finances of the Bass family.[19] After spending time camping out in the foothills north of Colorado during 27 straight days of rain, and with Lyman’s health continuing to decline, Frances swallowed her pride and reached out to Dr. Bell to inquire about staying at his Manitou Park Hotel. Though Bell did not agree to open the hotel himself, he proposed that the Bass family live in the hotel and oversee its operation over the summer while visitors from the east flock to the towns. Seeing this as “the one chance to save a man who would only return east to die,” Frances agreed to these terms. She did so in spite of protests from her now close friend Helen Hunt, who believed that their taking on responsibility for the Manitou Park Hotel would cause Frances to “lose all [her] friends.”

Following Dr. Bell’s suggestion, the Bass family hired a wagon and driver to transport guests, mail, and other services to and from Colorado Springs. The family also hired their camp cook from their time in the foothills to “go to the mountains” with them, along with an experienced chambermaid. It was agreed that the Bass' could stay for free regardless of the hotel’s success, but that any profits should be split between themselves and Dr. Bell. At the end of the summer, there was $790 to be split amongst the three of them.

During her time operating this hotel, Frances experienced the sort of first-hand disillusionment to the grandeur that was promoted by the towns of Manitou and Colorado Springs. Though the buildings were extravagant on the outside, the amenities offered on the inside still were lacking in comparison to more developed, east coast resort lodgings. She specifically mentioned that “all of the ancient families of bedbugs were in possession of the hotel. I carried at all times a blower of Persian insect powder, which I squirted in every crevice.”[20] Though this business venture was successful, the profits were hard earned, especially for someone coming from a life of affluence in New York. Frances stated that much of her time at this hotel was spent either spraying bedbugs, “scrubbing, washing, or reading Matthew Arnold’s verses in the black shadow of a stately pine.” She did, however, also make note of several guests of the hotel that could generally be categorized as well-to-do Englishmen, who were typical visitors and residents of the Pikes Peak region at this time.[21]

After this successful summer, the Bass family returned to Colorado Springs, with Lyman having his sights now set on a return home to New York.[22] Expressing this desire to Dr. Bell, Lyman received an offer from Bell and Palmer for “the position of general counsel for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad and associated Land Companies” in response. Likely due to their newfound reputation as effective caretakers and homemakers, this offer was contingent on Frances taking Dr. Bell’s wife to General Palmer’s home of Glen Eyrie, where she was to provide companionship and care to the “nervously ill” woman. Glen Eyrie is known to be a particularly picturesque location, even in the context of the Pikes Peak region, that sits one mile from the Garden of the Gods.[23] This natural beauty, coupled with the beauty of Palmer’s home itself, was reminisced upon fondly by Frances and well-represented in her albums.

In 1880, after this time in Glen Eyrie, Frances embarked on a visit to Twin Lakes, spending a night camping in the space that would eventually become Leadville, CO after gold and silver were discovered in the region.[24] Frances appeared to take great advantage of this opportunity to visit a lake, as the photographs featured in her album are mostly of sailboats resting on moving through the water. With regards to Leadville, it is clear that Frances does not lament the development of the area into a mining city. She describes prospectors as “the happiest of our men” at times, who worked hard and “walked where beauty reigned and the air was pure.” The photographs she includes of the area in this album are entirely of the region post-development, indicating along with these quotes a sort of fascination and some degree of envious wanderlust on the part of Frances.

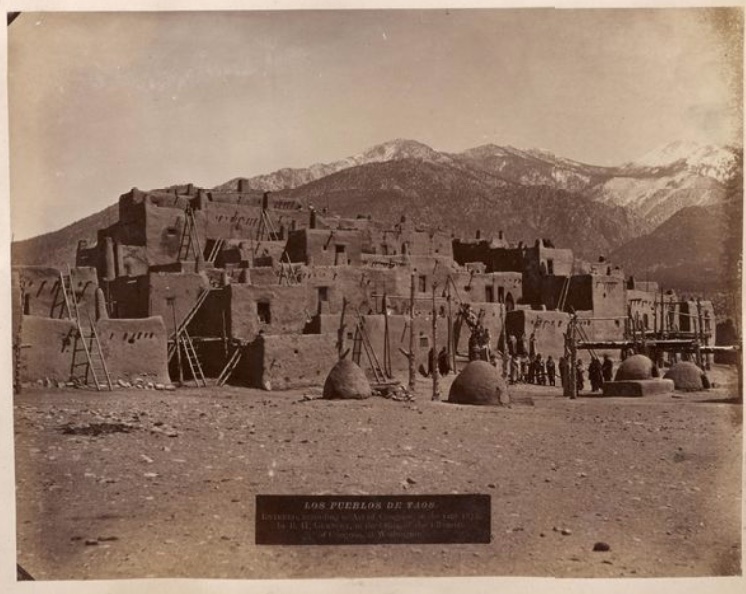

Sometime after this visit, the Bass family arranged a special car to bring them to New Mexico to witness “the Indian Harvest Festival of Saint Geronimo at the Pueblo of Taos.”[25] They were joined by Colonel Lamborne, said to be one of “the men of the railway circle” and his wife, who was identified by Frances as a sister of American author and diplomat Bayard Taylor. Their stop was twenty-eight miles from Taos, and they were transported by station agents to the city. Upon their arrival, they settled into their lodging in “white adobe houses” drawing inspiration from the historic “Pueblos of Taos” depicted in this album.

This festival was predominantly attended by members of Blackfoot and Apache tribes, with some of the more prominent members of these groups featured in this album. Frances made particular note of the intermingling of native and Catholic religious traditions, where a priest leads the participants in a procession to offer sheep as forms of sacrifice to their deities.[26] She added that such incorporation of multiple traditions is representative of how French missionaries “imposed the celebration of mass” without having “penetrated nor changed the tribal religious customs.” Being a woman of great prominence in the area, Frances was fortunate enough to have a meal with the priest that led the ceremony, who further relayed his admiration for Native American traditions and rituals. This was a sentiment shared by Frances, who expressed that “I shall never again see so thrilling a scene as that first sight of motionless Indians at the feet of Saint Geronimo.”[27]

Though this photo album predominantly depicts scenes of strong personal value to Frances, it is apparent that several of these photographs could be seen as mementos from Lyman’s excursions as part of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad organization. Towards the end of the album, there are photographs from Mexico, including photos of railways and the National Palace of Mexico City. These may have been taken during a visit by the Denver & Rio Grande Company to Mexico for the building of a Mexican national railway in the late 1870s.[28] Such talks occurred between Palmer and Porfirio Diaz, who at the time was president of Mexico. Palmer was “set out to enter Mexico from the north by private stagecoach,” and ended up signing contracts and commenced building the railway in Mexico. This project came to an abrupt halt, however, when Diaz was ousted from power in 1880. However, from these photos one can uncover the great amount of progress that was provided by the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad that likely laid the groundwork for the Mexican National Railway.

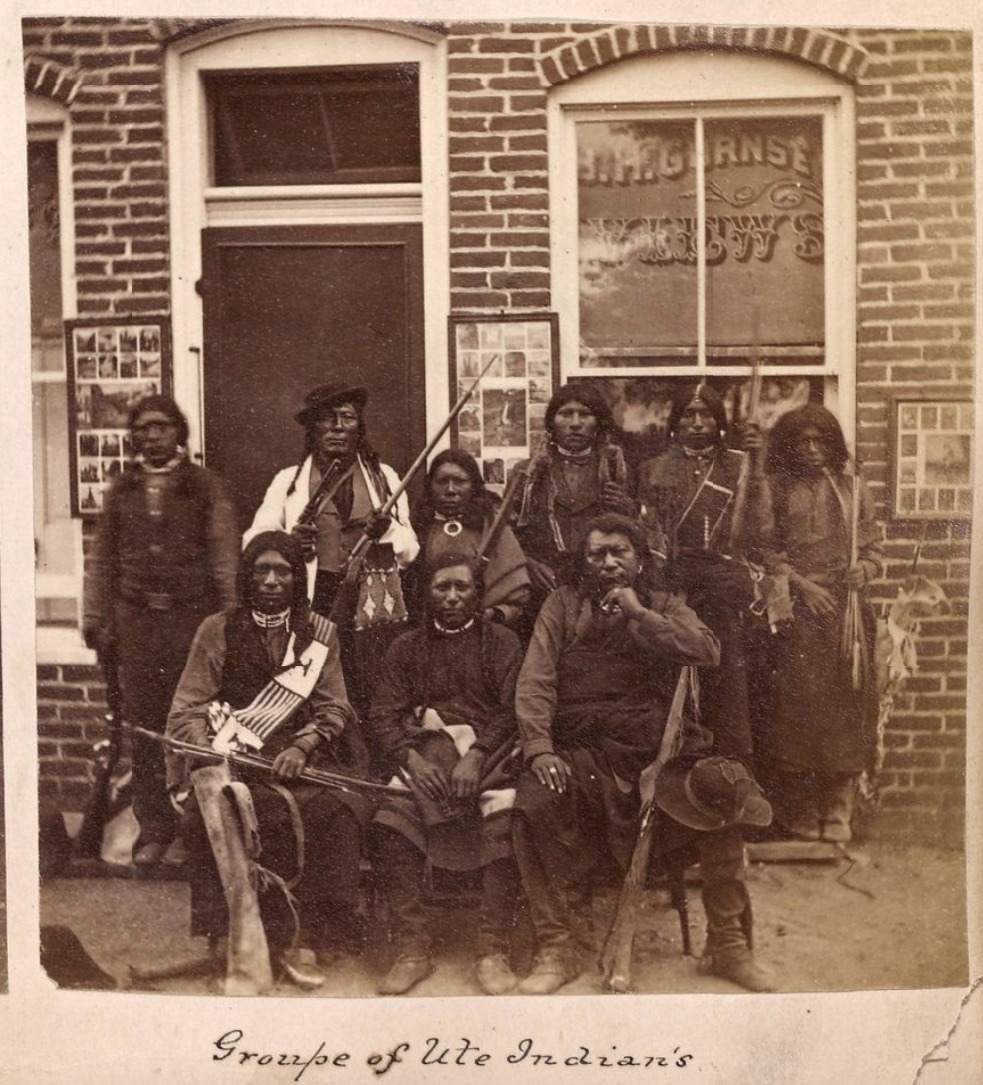

Regarding the origins of the photographs on display in this album, it appears that many of the photos originated with B.H. Gurnsey, a prominent photographer who relocated to Colorado Springs in 1872. Gurnsey had initially set up a photo studio in Sioux City to photograph soldiers and native peoples passing through the city on their way to D.C., but relocated to Colorado Springs to continue this mission and “take stereographic views of the local scenery and neighboring Native Communities.” [29] These stereographs include images of “Cheyenne Canon, Garden of the Gods, Grand Canyon of the Arkansas, Monument Park, Pike’s Peak, Ute Pass, Manitou, and railroad views.”[30] Though there are no stereographs in Frances’ collection, it is certain that many of these photographs were reprinted versions of the photographs that Burnsey used in his “Rocky Mountain Views” stereograph collection. These landscape and railroad photographs were taken between 1872 and 1880, and sold to Frances Metcalfe Bass or someone close to her in the shop seen above. Though Frances may have taken on many unexpected responsibilities during her time in the Pikes Peak region, it is apparent that “photographer” was a role that she graciously deferred to the experts. It is further known that several other photos were taken by other photographers, displaying this album’s emphasis on triggering memories over accurately documenting such experiences. In this sense, it is clear that these photos were not special at the time due to their rarity, but rather due to the personal memories held by the Bass family that these photos call back to.

This album is representative of a collection of memories for the Bass Family in their adventures living in the Pikes Peak region, playing a major role in the early development and upkeep of the cities founded by Dr. Bell and General Palmer. This collection may represent a thoughtful gift provided by Lyman to his wife, to remind her of their adventures together and display his pride in the work that he accomplished in his time working for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. Such memories would certainly be valuable for Frances during the frequent periods in which they were separated due to other obligations. After spending so much time preoccupied with the politics of the east coast, it appears that the Bass family was able to start anew in collecting shared memories and experiences from the change of scenery and lifestyle that their time in the region mandated.

This album is then representative of this sort of self-reconfiguration that was so desired by those who visited the Pikes Peak region. Though others may have found peace in the hot springs, it is apparent that the Bass family strengthened their familial bonds through their shared experience living in a slightly polished but still relatively untamed area of the West. They arrived, and made their mark, on the Pikes Peak region at a critical stage in its development, and participated in activities that served to push this development along. Though the resort frontier may have been intended to promote an image of luxury and relaxation running in refreshing contrast to dominating narratives of the West, from this album it is apparent that the western frontier served as a great equalizer for persons from all walks of life. Though the Bass family may have found new energy in the Pikes Peak region, they were also a far cry from the luxurious lives they had led back East.

[1] Frances Metcalfe. Wolcott, Heritage of Years: Kaleidoscopic Memories (New York: Minton, Balch & Co., 1932), 69.

[2] “SENATOR WOLCOTT MARRIED; THE YOUNGEST MEMBER OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE WEDS MRS. BASS.” The New York Times, May 15, 1890.

[3] Wolcott, Heritage of Years, 47.

[4] Ibid, 41, 44.

[5] Cynthia Ambriz, "William Jackson Palmer," Colorado Encyclopedia, 2018, accessed April 10, 2021.

[6] Ian Brabner, "A Grand Cañon War: Guns & Mobs in 1879," Medium, August 14, 2015, accessed April 10, 2021.

[7] Mel McFarland, "Dr. William Abraham Bell and His Ties to the Pikes Peak Region | Caboose Cobwebs," Pikes Peak Courier, October 13, 2020, accessed April 10, 2021; Wolcott, 67.

[8] Wolcott, 68.

[9] Ibid, 69.

[10] Ibid, 69-70.

[11] Matt Mayberry, "A Brief History of Colorado Springs," Colorado Springs: Olympic City USA, 2008, accessed April 10, 2021.

[12] Wolcott, 70.

[13] D. Appleton, Appleton's Illustrated Hand-book of American Winter Resorts (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1884), 76.

[14] "History and Heritage," Visit Colorado Springs, 2021, accessed April 10, 2021.

[15] Mayberry.

[16] Wolcott, 71.

[17] Ibid, 72.

[18] Ibid, 76.

[19] Ibid, 78.

[20] Ibid, 79.

[21] Ibid, 79-81.

[22] Ibid, 84.

[23] Appleton, 77.

[24] Wolcott, 93.

[25] Ibid, 94.

[26] Ibid, 95.

[27] Ibid, 96.

[28] Ibid, 125-6.

[29] Nathan Sowry, "Byron H. Gurnsey Sterograph Collection," Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives, 2020, accessed May 1, 2021.

[30] Byron H. Gurnsey, "Gurnsey's Rocky Mountain Views," Library of Congress, 2021, accessed May 1, 2021,