Between Prosperity and Struggle: The Story of Nome, Alaska in the Early Twentieth Century

By: Robert L. Anderson '23

In 1900, one man described Nome, Alaska as “the strangest community ever seen upon the face of this old earth.”[1]

The Photographic Album of Nome

In the confines of Princeton’s Firestone Library rests a large photographic album showing Nome, Alaska and the surrounding areas during the late 1920s and early 1930s. As part of Princeton’s Collections of the American West, the photographic album depicts life in this “strange” community through what is most likely the perspective of a “Nomeite.”[2] The 167 pictures thread together a story of the inhabitants of Nome, that suggests a mostly stagnant life after the Gold Rush at the turn of the 20th century. Moreover, surrounding campsites and townsites are shown throughout the album. Unattributed, and mostly uncaptioned, these photos capture the story of a city that was mostly unaffected by a national economic crisis, a city that saw great prosperity, but also great struggle.

The identity of the photographer cannot be confirmed. However, the photographs appear to be from a photographer(s) from the Lomen Brothers Company. The photography studio was founded in Nome, Alaska in 1908 by the four Lomen Brothers: Carl, Harry, Alfred, and Ralph. The Lomen Brothers Co. regularly captured a variety of subjects related to Nome, like the surrounding areas, the mining operations, business operations, dog sled teams, ships and aviation, and indigenous communities in Alaska,[3] all of which are represented in the photographic album. The Lomen Brothers stamped most of their photographs, although not all of them. In the album, the photograph of pilots Harold Gatty and Wiley Post is stamped “Lomen Brothers.” Because the rest of the prints in the album are similar in style and composition to other Lomen Brothers prints, it is compelling to believe that this collection of photographs once belonged to the Lomen Brothers.

A tragedy for the Lomen Brothers Co. occurred after the 1934 fire in Nome destroyed their entire studio along with 25,000-30,000 negatives and 50,000 commercial prints. Only about 3,000 negatives were salvaged, and that was the last of the Lomen Brothers photography business.[4] The photographs in the album could be a combination of commercial and private photographs, although it is hard to decipher which is the case. The organization of the album might be a response to the fire that caused the loss of nearly 30,000 prints, and an effort to salvage the remaining photographs. While there is no particular order or pattern in the album, there are clusters of subjects scattered throughout. The fact the album is unfinished could suggest that the collector ran out of prints to fill the album after the fire, but that is not confirmed.

The people that traveled to Nome in 1900 represented countries from around the world. Individuals born in Germany, Greece, Scotland, Japan, Russia, and various American states were reported in the 1900 United States Federal Census in Nome.[5] Maybe this is why historian Terrance Cole called it “one of the strangest gold rush boom-towns in the history of the American West.”[6] And while the modern-day version of the city is merely a shadow of what it once was, the small town on the Seward Peninsula in Western Alaska is the most famous gold rush town in Alaskan history. From just a few thousand inhabitants in 1899, the community grew into a vibrant city of 28,000 in just the span of a few months. However, that was early Nome. And while the photo album captures a mining town full of culture, it is the life of Nomeites 20 years after the most famous gold rush in Alaska. Yet the storied history of the great gold rush town cannot be overlooked. The environment, people, and cultures captured in the album would not be the same without the 1900 boom in Nome. Therefore, a brief history is as follows.

Nome Fever

Thousands of people stampeded the beaches of Nome in the summer of 1900 with the hopes of striking it rich.[7] However, traveling to Nome was not an easy task. The city is located on the Southern Seward Peninsula coast on the Bering Sea. Nome is about 540 air miles northwest of Anchorage, the equivalent of a 1 ½ hour flight; the community is not part of Alaska’s road system, making it nearly impossible to drive there.[8] The city of Nome is closer in proximity to Russian land (about 507 air miles) than it is to Washington State (2,008 miles), the nearest American soil. However, the prospect of gold still brought an influx of stampeders to Nome despite its remoteness.

The prospectors’ campsites along the Snake River became a city of nearly 20,000 people in the span of a few weeks; most of the gold seekers and fortune hunters only stayed a few months. However, as Cole proclaims, the Nome gold rush was the last major gold rush in America’s Western history, leaving Nome as the last of the towns in the history of the boomtown lore. [9]

The easy diggings on the Nome beaches made the small city on the Seward Peninsula attractive to gold seekers; the wide-open beaches meant there was plenty of space for people to dig for gold. The “City of Golden Beaches” brought to Nome a rush of people, technology, and materials that in no way could the Inupiat inhabitants living there could have ever prepared for. One can see people sailing ships to the beaches, unloading their materials and leaving them docked in the sand.

The gold rush shaped the Nome economy for years to come; it brought new cultures of people and helped Nome become a city with a formal main street, a Coast Guard, and a hotel with over twenty available rooms. In fact, the gold rush is said to have been the foundation of an estimated quarter-billion dollars in gold, and Nome came to be known as the “metropolis” of the cold Seward Peninsula.[10] The city prospered for a few years as the largest city in Alaska, and while the craze in Nome eventually slowed down, it remained a vibrant city up until the first World War.

In a span of twenty years, the city went from a prosperous gold mining town that led the Alaskan economy to one that was nearly wiped out during World War 1.

Throughout Alaska, and particularly in Nome, city populations and gold production levels declined dramatically during World War I. While gold production had been declining for years before the War began, the gold mining industry as a whole collapsed as a result of the War. In Nome, gold production levels declined more than two-thirds between 1916-18.[11] And as the album captures Nome’s “hardest years” in the 1920s and early 1930s, the city was one whose energy and life was constantly fluctuating.

Culture in Nome

The photographic album captures the mix of culture in Nome. The 1930 United States Federal Census logged 2,849 people living in Nome, and Alaska was the birthplace to only 965 people, suggesting the lasting impact of the gold rush on Nome’s population. Of those 2,849, 1,175 were female (not attributing differences in age). [12]Women were important contributors to society; this can be inferred from the number of women recorded in the 1930 consensus as well as a high female presence since the gold rush.

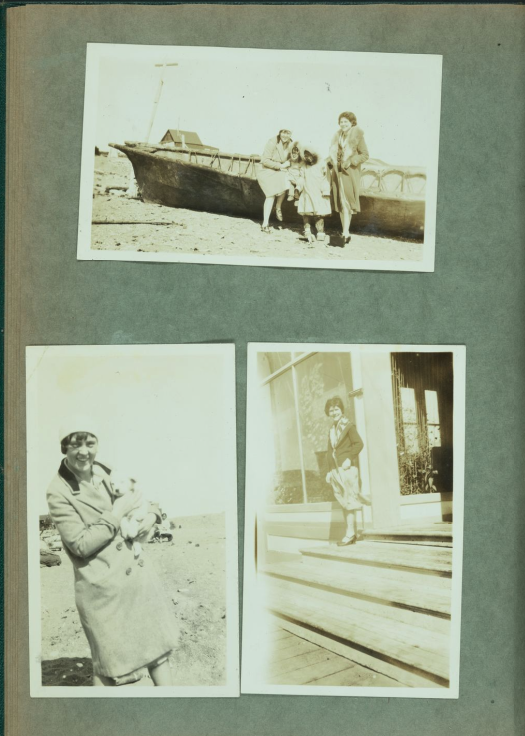

Quite a few of the photographs capture women in Nome; the influence of women in society was everywhere. Historian Preston Jones proclaims that there was very little social conflict of any kind in Nome in the first thirty years of the 20th century because life in Nome was enough of a challenge, and social disagreement was not what Nomeites spent their time stressing over.[13] Hence depicted in the album are women smiling, working in the fields, taking care of children, and actively engaging in the Nome community.

Yet no women were captured mining in the album, which seems logical as women would tend to homes, catch fish for dinner, and help take care of children while the men went to work mining for gold. Multiple photos portray women catching and cutting fish for a later meal.

Iñupiat people are well represented in the album as well.

The Iñupiat people have long lived in the area around the Bering Strait,[14] and they often camped on the beach near Nome during the summertime. Many would travel hundreds of miles in their kayaks in order to be in Nome during the summer. In Nome’s early years around the time of the gold rush, Nomeites would often project anti-native feelings towards Iñupiat people. However, once Nome achieved stability there was a much warmer feeling towards the Natives, and it did not take long before the Iñupiat people were welcome as Nomeites’ “assistants, workmates, fellow traders, fellow Christians, and customers.”[15] In the album, Natives are captured throughout the city. One image captures a white man posing in front of a Native woman’s home as her child hides behind the mother’s legs.

Nomeites quickly felt the influence of the Iñupiat people. Photographs in the album reveal that Nomeites began to dress like their Native friends, particularly in the winter months. Native clothing became a popular Nome feature, below are a group of women posing in Native dress. Another photo captures a white woman standing proudly in a Native-influenced jacket. The Native children roamed the Nome streets and spent time on the sandy shores. Natives were an important aspect to Nome’s culture.

Nome was one of the most inaccessible places in the world during the winter when the Bering Sea was covered with ice, but the city was easily reached by boat between the months of June and October

One of the major stories of Nome captured in the photographic album is the weather. Winter in Nome pushes people away. In 1899, Alaska District Judge Charles Johnson urged leaders to provide services to the few thousand people that remained in the city after the summer to survive winter. Yes, to survive. [16] It was never a matter of getting comfortable, but rather about survival.

You can see ships iced in on the shores of Nome. Before the development of official transportation routes, Nome was not easily accessible. One could walk, or sail, but with no promise of an easy trip. The winter months meant no ship access, and certainly no foot access given the roughly 76 inches of snow the town gets per year. When ships were able to sail the cold Bering Sea up to Nome, massive quantities of food and other supplies were delivered to residents to live through the months of winter.

Moreover, it is interesting to think about what it means for the photographer to walk the streets of Nome in the winter months. Nome’s emptiness during the winter is certainly captured in the album, as roughly only 20 of the photographs are images of the winter. In one, a man walks alone passed the snowed-in carpenter shop, suggesting businesses are not open year-around.

Or, see a man and a woman pass each other on main street near the “Miners and Merchants Bank of Alaska.” Streets are empty, shops appear closed, and the piles of snow amount to heights that nearly double some of the people living there. Even these photos are suggestive of Winter’s end, as some snow begins to melt, and the optimism of the summer is near. However, snow does not disappear overnight, and the bleakness of the winter months are felt long after the last drop of snow.

Winter life in Nome was not as terrible as it may seem, however. Dog racing was the most famous winter sport in Nome, and many were able to ski and sled on Dry Creek. [17] With plenty of snow, skiing and Dog Mushing were popular, and wintertime activities became a means to stay busy in a city that was secluded during winter. Summertime in Nome was far different, however. In the summer, traveling vaudeville shows traveled to the town, and the 4th of July was the peak celebration for Nomeites. Visitors, children, women, parades, and a plethora of festivities dominated the streets of Nome between June and October. The busiest day of the summertime meant people gathered to celebrate and enjoy time together. While Nome was a temporary home to many, it was a permanent home to few.

Life in Nome during both the Winter and Summer Months. Courtesy Princeton University Library.

Transportation

There was also the establishment of a formal dock for boats to pull up to shore. In the early years, docking a ship on the beach was the norm. However, the development of the dockside marina made Nome even more accessible in the summer. The album captures various images of motor boats named “Ukiuwak,” “Silver Wave” and “Sea Wolf.” Nome was easily accessible in the summer and people traveled north on ships in order to get there.

The 1931 Flight Around the World

Harold Gatty and Wiley post on their 1931 Flight Around the World. Courtesy Princeton University Library.

One of the Lomen Brothers photographers captured pilots Wiley Post and Harold Gatty with their airplane “Winnie Mae” during their 1931 flight around the world. While it was in 1911 when roughly a thousand people showed up behind the wireless tower in Nome to witness the first airplane flight in Alaska, Nome did have hope in the 1930s to become an international aviation center due to its strategic location.[20] And although it never became the international aviation power that it had hoped for, it was a consistent stopping point for Alaskan Airlines routes.

Economy and Technology

Prosperity from the gold rush in Nome eventually ended leading up to World War I. For some time, however, the development of effective transportation systems, and the influx of visitors in the summer months led to a Nomeite belief that there was no foreseeable end to the golden beaches and the success they were bringing. To survive as an economic entity, however, Nome needed an advantage geographically.

After the gold rush settled down, Nome saw a stagnant economy in the 20s and 30s. The Golden Gate Hotel was run down and renting fewer room annually than it was in years past, and the ratio of empty houses to inhabitants was slowly increasing.[21] Travelers during this time period marveled at the number of abandoned buildings that plagued the streets. One travel noted in his diary, “the whole town of Nome is a startling reminder of its former affluence…Few of the houses and stores are occupied and with the exception of the houses of the members of the Lomen family, and their store, all are going to rack and ruin and many look as though they were about ready to fall with the next storm.” [22] The album captures empty streets, broken down storefronts, and uninhabited buildings.

The Hammon Consolidated Gold Company purchased the property of the Pioneer Mining Company, and a massive shift from hydraulic mining to dredging followed.[23] The dredging machinery that developed in Nome throughout the 20s is captured a number of times in the photographic album.The technological advancement of dredging brought a glimpse of prosperity and hope back to Nome. Miners found work again, businessmen opened their stores up, and the economy saw a slight boom. In 1925, for the first time since before the Great War, gold production in Nome totaled as much as $1 million in a year.

The technological advancement of dredging brought a glimpse of prosperity and hope back to Nome. Miners found work again, businessmen opened their stores up, and the economy saw a slight boom. In 1925, for the first time since before the Great War, gold production in Nome totaled as much as $1 million in a year, [24] hence the small mining campsites captured in the album. Nome was investing in gold mining once again, and miners were being put to work. While some miners in the album smiled, others showed little emotion. A businessman and a miner stand side by side, showing two sides of the business. Maybe this glimpse of prosperity is suggestive of the owners proudly standing in front of their storefronts in the album, like Leo Seidenberg captured in front of his Bon Marche Store.

Various photographs of miners, mining sites, and the storefront of Bon Marche. Courtesy Princeton University Library.

As the Great Depression unfolded in Nome, locals feared the town would suffer. Yet that was not quite the case. Nome’s population and gold production plummeted more during the Great War than during the Great Depression. Because Nome’s economy was essentially operating independently of the nation’s economy, Nome remained relatively unscathed in terms of the nationwide impact of the Great Depression. As Nome legislator Henry Berg proclaimed in a 1932 issue of the Daily Alaska Empire, “There’s no depression in Nome…There’s no bread lines or municipal soup kitchens in Nome, and all of the local residents are at work, many of them mining for themselves.”[25]

Indeed, despite the album capturing life during the years of the Great Depression, mining activity remained. Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected as president in 1932, giving many the hope that he would lead the nation out of the Great Depression. An early measure of the New Deal was that FDR doubled the price of a gold ounce to $35 in 1933.[26] This helps explain the many mining plants and machines captured in the photo album.

A great fire in 1934 nearly wiped out the entire city. Like the Lomen Brothers Co, many businesses were destroyed and buildings burned down. Life after the great fire of Nome shows promise for future studies, however. Nome is a city built on Golden Beaches and hope. The fluctuation between prosperity and failure captured in the photograph album tells a larger story of Nome. It is a city that blends cultures, and its life is weather dependent. Today, Nome is a mere ghost of what it once was. But this album reveals that Nome was able to prosper even after the gold rush ended; that Nome’s remoteness, culture, and history make it a fascinating and unique city

[1] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches. (9)

[2] Like many communities and states that have nicknames for those that live there, inhabitants of Nome came to be known as “Nomeites”, as depicted in a series of the Nome Nugget, and originally explained in Empire’s Edge

[3] “Lomen Brothers Studio Copy Negatives from Alaska and Canada | National Museum of the American Indian.” Accessed May 3, 2022. https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/sova-nmai-ac-164.

[4] Ibid

[5] “All 1900 United States Federal Census Results - 1900 United States Federal Census - AncestryLibrary.Com.” Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/search/collections/7602/?residence=nome-nome-alaska-usa54947&residencex=1-0&fh=20&fsk=MDsxOTsyMA-61--61-.

[6] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (57).

[7] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (9).

[8] “Relocation Guide.” Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.visitnomealaska.com/relocation-guide.

[9] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (9).

[10] Ibid, 128.

[11]Ibid, 128.

[12] “All 1930 United States Federal Census Results - 1930 United States Federal Census - AncestryLibrary.Com.” Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/search/collections/6224/?residence=nome-nome-alaska-usa54947&residencex=1-0.

[13] Empire's Edge : American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934 (19)

[14] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (17).

[15] Empire's Edge : American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934 (6).

[16] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (41).

[17] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (147).

[18] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (118).

[19] Empire's Edge : American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934

[20] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (182).

[21] Empire's Edge : American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934 (19).

[22]Ibid.

[23] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (138).

[24]Ibid.

[25] The Daily Alaska empire. [volume], July 12, 1932, Page 3, Image 3.

[26] Cole, Terrence. Nome, City of the Golden Beaches (156).