Depicting the People of the Blue-Green Water: George Wharton James and the Havasupai Indians of the Grand Canyon

By: Meredith L. Summa '22

Access George Wharton James' digitized album, The Havasupai Indians of Arizona, via Princeton University Library.

I thank thee, dusky brother of the plains, the mountains, the forests, and the canyons, for this lesson and all the other lessons you have taught me. I am grateful for the lessons of the higher civilization. I prize and treasure them, but equally am I under obligation to thee, thou red-skin, for recalling to me some primitive principles which civilization ignores at its peril.

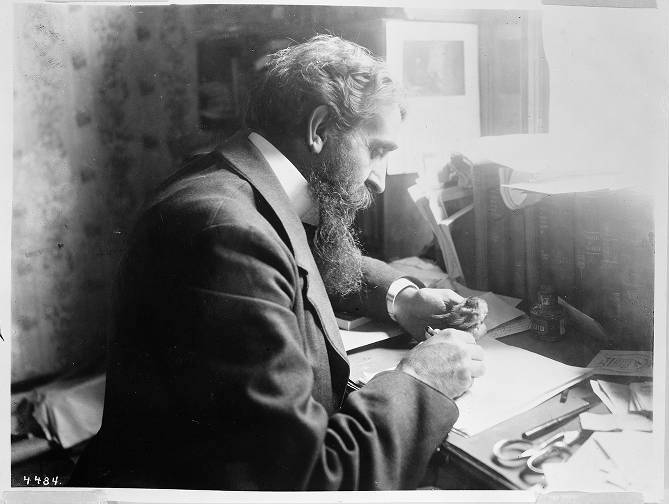

George Wharton James (1858-1923) grew up in an English Methodist dissenter home where “try something different and see if it will work” was the guiding principle. His parents were reform-minded, encouraging their children to explore beyond the confines of society. This tenet would prove to be central throughout James' life, inherent in his ventures as a preacher, naturalist, and author of the American West.[2]

George Wharton James would become an ordained minister, immigrating to America in 1881. He gained a substantial following among the faithful, serving towns in the Southwest before settling in California.[3] He preached a somewhat unconventional doctrine, believing that an active physical, mental, and spiritual life was the optimal path toward redemption. Consistent with the contemporary liberalization of Christian thinking among the middle class, he gravitated away from orthodoxy. Instead of striving for a far-off heaven, James exalted the principles of love, peace, fraternity, and progress in everyday life. The itinerant preacher even distanced himself from scripture, stating that rather than relying upon the Bible, he takes his text from “God’s other book, His world - Nature.” For James, religion was self-revealing, a principle that resonated with his growing audience.[4]

But in 1889, James fell from grace: unfounded accusations of deviant sexual practices from his wife and the difficult divorce that followed knocked the seasoned minister from his pulpit. In just one example of his defamation by the press, in an April 1889 article, a Los Angeles Times journalist named him “Ir-Reverend James.” The Methodist Church, however, was less steadfast in its denunciation, coming under fire for condemning the controversial minister and then reversing their decision soonafter. Whatever the mechanism of his ousting, the scandal left James in a state of disgrace. He resigned from the Church during the same year, leaving him penniless and shunned by his community.[5]

It was in this state that James decided to embark upon a journey through the "uncivilized" Southwest, leaving California in 1889 to explore the natural landscapes of Arizona and New Mexico and take in the beauty of the canyons, deserts, and forests of a land still largely unknown to white Americans.[6] Consistent with his reformed religious beliefs, his travels were also his path to redemption. He affirms: “In the desert the soul of man finds itself as nowhere else on earth. Here are solitude and God, both necessary, and the only necessaries, to the full awakening of the human soul.”[7] Far from “civilization,” James slept in the open air, learning outdoors skills from those he encountered and even staying with and befriending Indian people he met.[8] Throughout the 1890s and into the early 20th century, James continued to venture out of society, taking lengthy trips to seek a simpler way of life in the refuge of nature.

In the desert the soul of man finds itself as nowhere else on earth. Here are solitude and God, both necessary, and the only necessaries, to the full awakening of the human soul.

However, James did not return empty-handed. Throughout his travels, he kept extensive records of his experiences. Starting in the early 1890s, James lugged photographic equipment alongside him. He took pictures of the land and the people he met on the way and documented fragments of his interactions during his journeys.[9] Armed with this wealth of information, James transformed his life and bolstered his reputation through a new career as a prolific travel writer, authoring dozens of books and pamphlets on the region’s lands and the Native tribes who inhabited them.[10]

His dizzying literary output of over 70 volumes ranges widely, from practical travel guides to social criticism to published sermons.[11] Although some contemporaries denounced him as a “literary racketeer,” his works were read widely, and a number of his books reached acclaim.[12] Like other western writers of his day, James espoused a view of the West as a place of spiritual remediation, personal growth, and opportunity: A land where man, marveling at God’s creation, can reform his life. This message evidently carried weight for James personally. Although his reputation remained controversial during his lifetime and beyond, he was able to renew his livelihood through the pursuit of knowing and exploring the Southwest.[13]

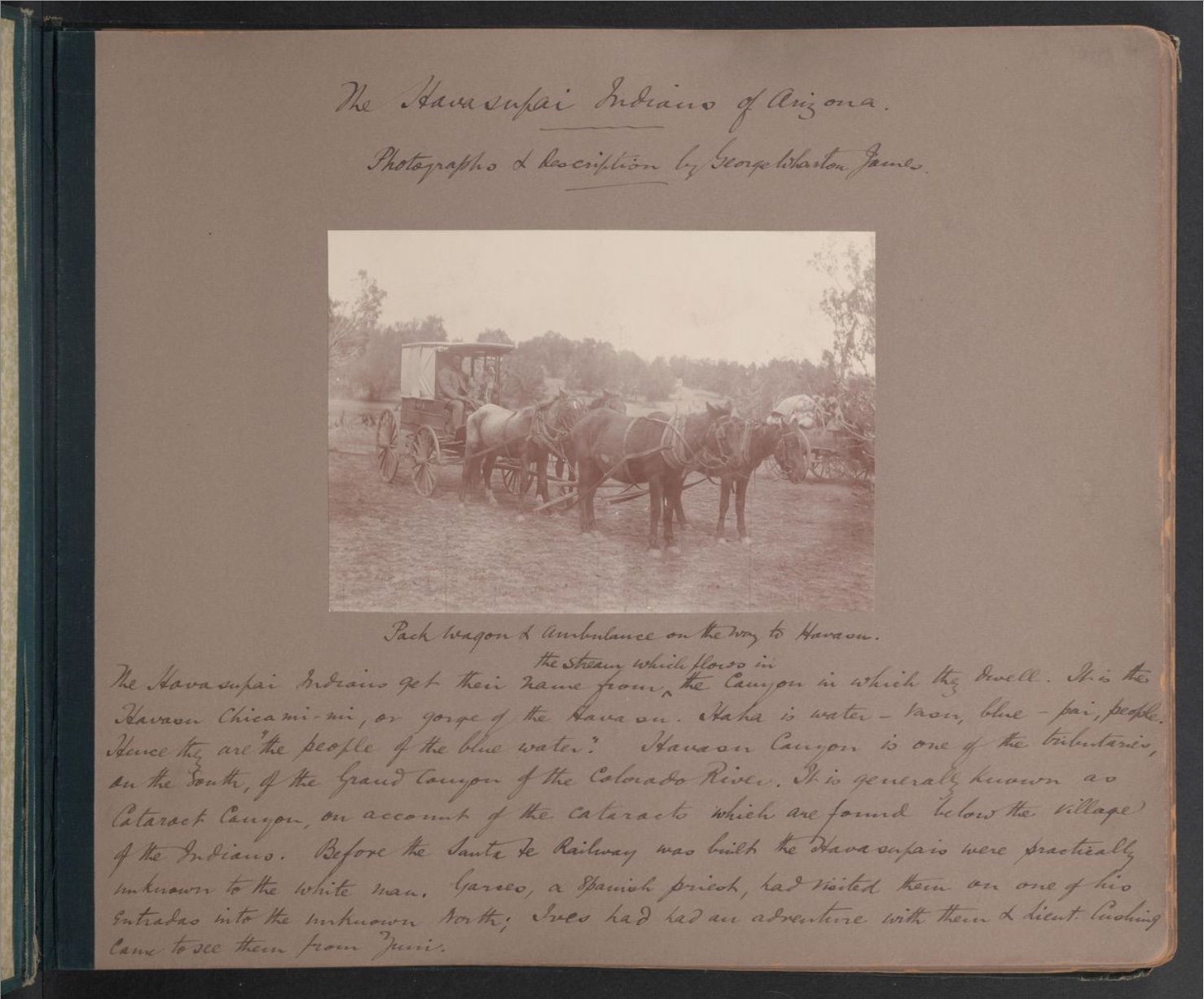

Although his published texts and photographs are readily available through online and print resources, the collections of Firestone Library contain a unique work authored by James: a vernacular album. Unlike many of his other works, evidence suggests that the album was not intended to be reproduced and sold to a wide audience. As Martha Sandweiss states in her book, Print the Legend: Photography and the American West, with the advance of photographic technology in the mid-nineteenth century, images were able to be printed, allowing for their publication and widespread circulation. This enabled an expansion in the commercial market for “photographic views of Indian life,” transforming the photograph from an object of “private remembrance” into “a piece of a public story.” [14]

Yet in contrast with a commercial product such as a catalog of views made for order or a published book, James’ album is evidently personal. For one, there is no pricing or size information given. Additionally, there is a lack of uniformity in his captions, both in their length and content. His annotations are also handwritten, and the photographs are not the same size or position across the pages, giving the album a scrapbook-like quality. All of these components suggest that James made the album for his own records or perhaps to share with close family and friends upon his return.

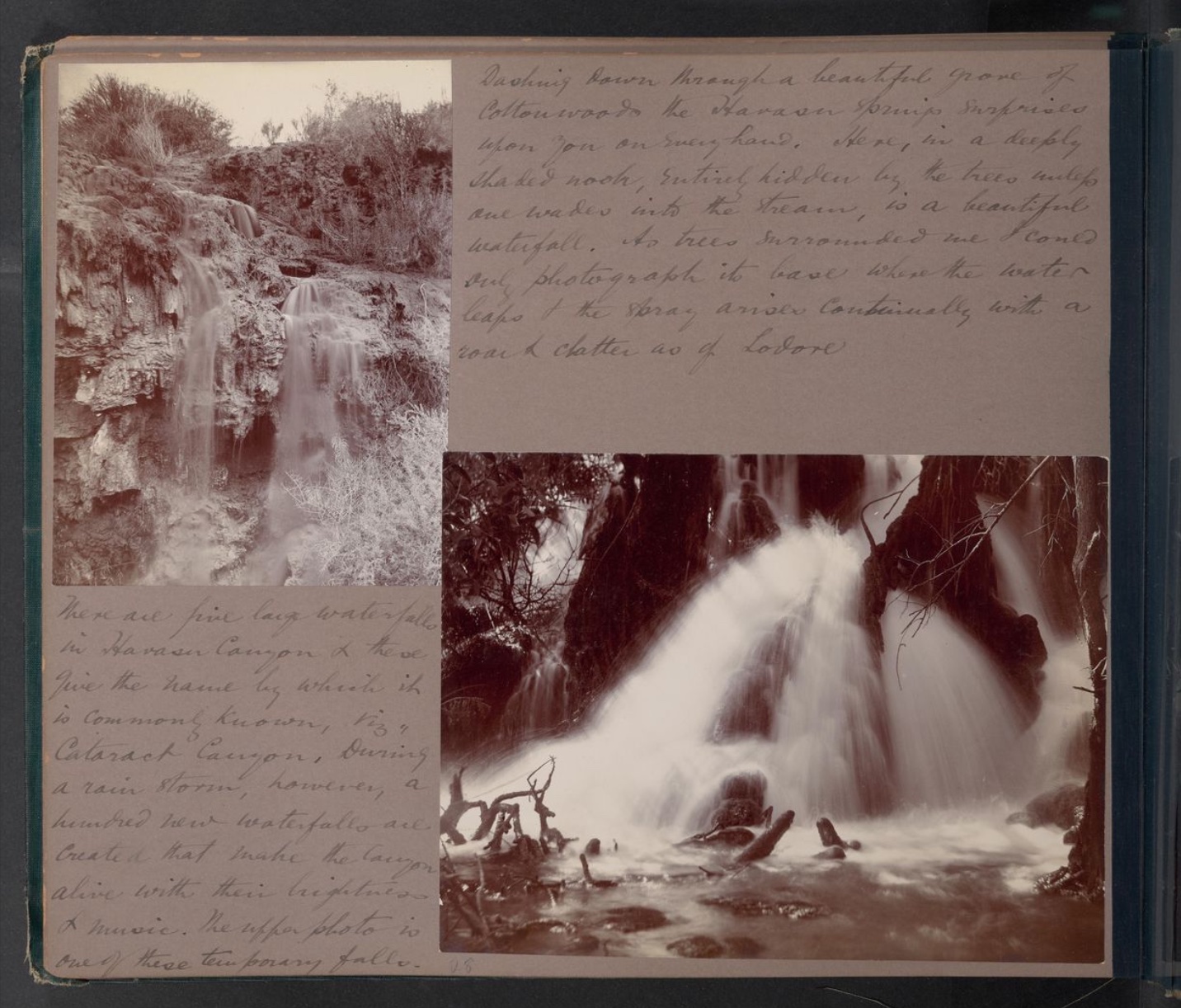

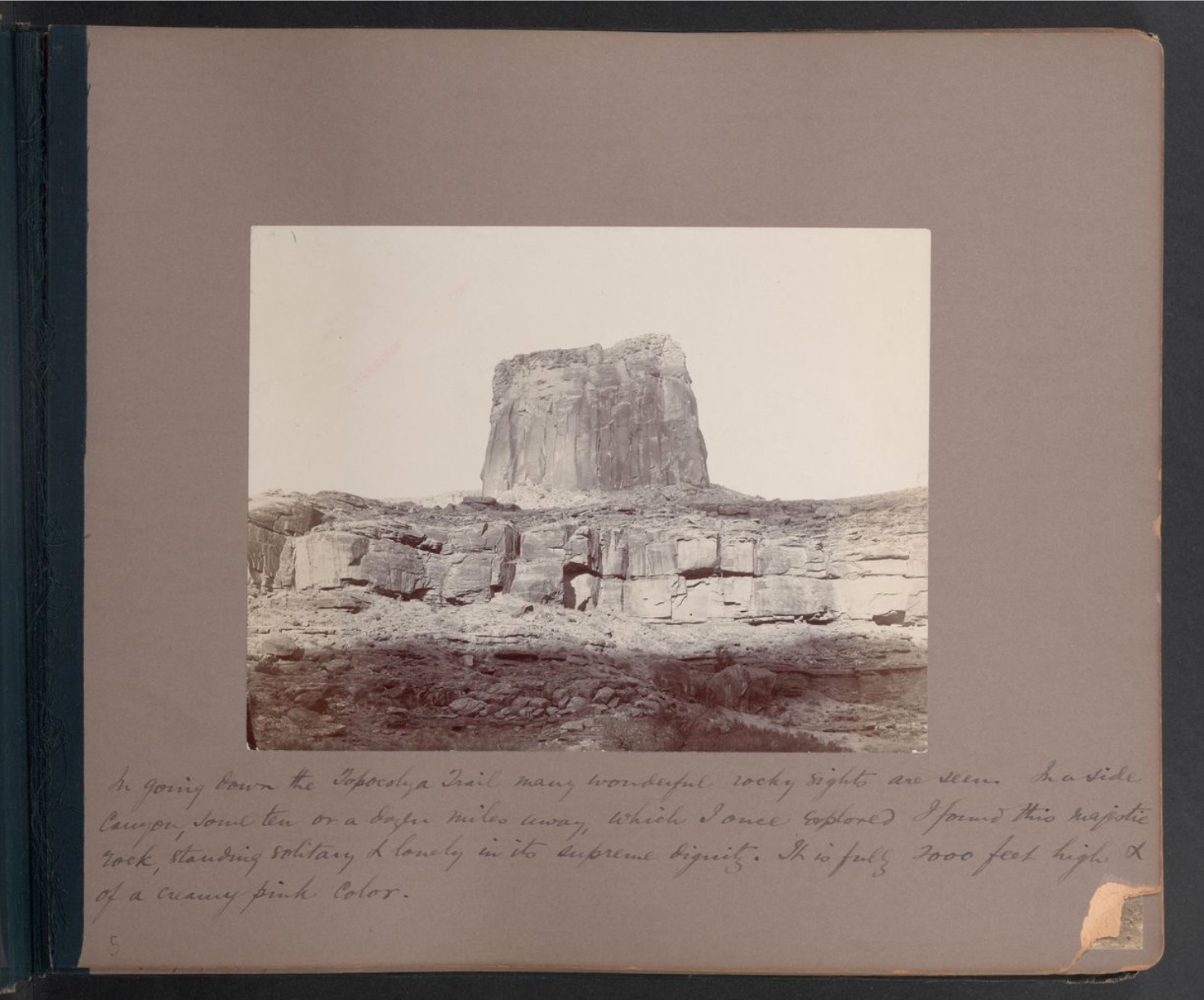

In terms of its content, the album centers on the people and territory of the Havasupai (People of the Blue-Green Water) of Arizona, who lived on the lands in and around the Grand Canyon. It was compiled at the turn of the century in the year 1900 and contains 40 prints from wet plate negatives as well as a handful of clippings from "The Wide World Magazine" which features an article by James with some of his images embedded in it. Each page of the album shows fairly extensive descriptions and contextualization of the photographs, handwritten in pencil by James himself, as confirmed by congruent handwriting found in letters the photographer wrote.[15] His subjects include rock formations, waterfalls, landscapes, animals, as well as some constructed structures.

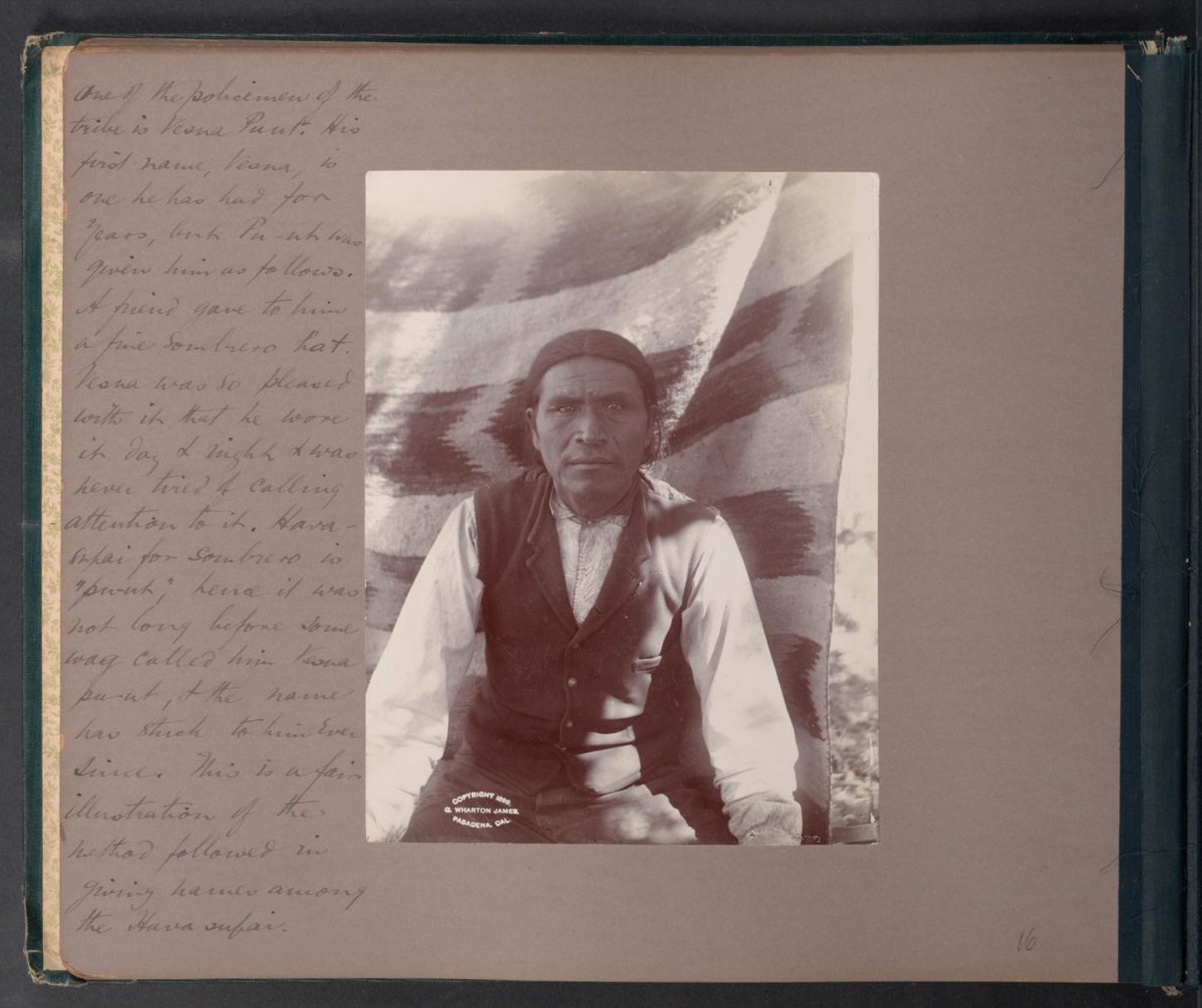

Importantly, his album also features portraits of the Havasupai themselves, his subjects ranging from tribe leaders to female basket weavers to children. Notably, James’ photographs of the Indians he includes in this album show that the Havasupai were aware of their image being captured. Almost all of the photos feature people who look straight at the camera. The images are split between some that are posed and others that are more natural. Also, the majority of the photographs are taken from a close distance, another feature which signifies that the subjects were aware of their photographer.

This idea of the consent and agency of the subject is especially important when considering nineteenth century photographs of Native Americans. It is often wrongly assumed that every photograph of an indigenous person from this time period was entwined with a larger narrative of imperialism. As Martha Sandweiss explains, although it is true that many were in fact used to endorse harmful political agendas and racist ideas, “Nothing embedded in the very concept of photography itself dictates such a use of the pictures” [16] On the contrary, just like any other subject, the Native person or people photographed could have their own reasons for having their likeness taken and were active participants in the photographic process. Sandweiss states: “To imagine that every photograph of an indigenous person represents an act of cultural imperialism is to deny the ambitions of the sitter, the capacity of that sitter to understand the collaborative process of portrait making, and the cultural malleability of any photographic image.”[17]

To imagine that every photograph of an indigenous person represents an act of cultural imperialism is to deny the ambitions of the sitter, the capacity of that sitter to understand the collaborative process of portrait making, and the cultural malleability of any photographic image.

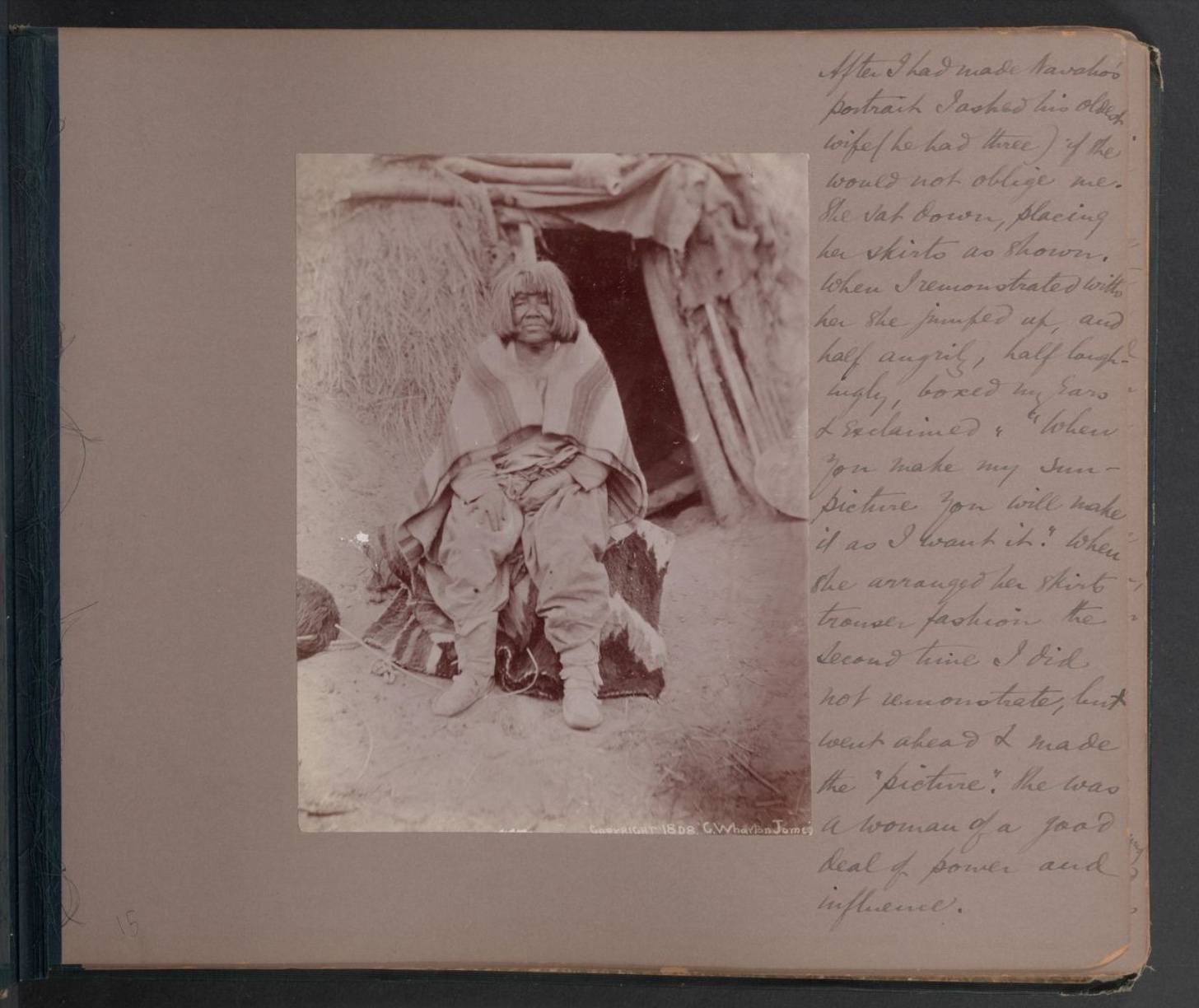

A photograph of the wife of the former chief (Kohot), called Navaho, is accompanied by the following description of the photographic process which illustrates this question of the agency of James’ Havasupai subject:

After I had made Navaho’s portrait I asked his oldest wife (he had three) if she would not oblige me. She sat down, placing her skirts as shown. When I remonstrated with her she jumped up, and half angrily, half laughingly, boxed my ears and exclaimed, "When you make my sun-picture you will make it as I want it." When she arranged her skirts trouser fashion the second time I did not remonstrate, but went ahead and made the "picture." She was a woman of a good deal of power and influence.

This passage is interesting as it communicates James’ relation with one of his subjects. She is clear about her terms and conditions for being photographed, and James, albeit reluctantly, does follow through with them. The tone of his writing is jovial even though it communicates a conflict between him and the oldest wife. In the end, he defers to his subject.

Interestingly, this encounter is reproduced in James’ 1903 The Indians of the Painted Desert Region. He recounts the influence she had, stating that she “ruled the roost.” In exchange for persuading her husband, former Kohot Navaho, to sit for a photo, she demanded her own likeness be made. James recalls how she “secured her petticoats between her legs in such a manner as to make them appear like rude trousers,” and his protest against the “unfeminine appearance.” In a similar tone to the photograph’s annotation in the album, he describes that the former Kohot’s wife “boxed my ears with a manner at once decisive, haughty, and jocular, and bade me proceed as she was or not at all.”[18] In this instance, the text of the album and that in the book are in accordance with each other, the book’s text providing further details on the wife’s role in the making of her photograph. It is revealed that not only did she agree to have her picture taken but she actively sought out James’ camera.

This brief example illustrates the many uses of James’ photographs that must be taken into account before delving further into his work. As stated above, the vernacular album James created in 1900 is distinctive for its seemingly private, uncommercialized quality. However, the photographs within the album are not unique across James’ body of work. Many of the images are reproduced in his books, and their use and meaning is therefore altered. Sandweiss states: “The portrait that once memorialized a personal, private moment is easily reimagined as a public commodity, the record of a specific historical event reembraced as an ahistorical visual metaphor.”[19] As we will see, the images and handwritten annotations of James’ album were frequently incorporated into the prolific author’s larger oeuvre. In the process, the material was altered to varying degrees, sometimes losing its original identity completely while other times retaining it.

On the tenth page of the album, there is a photograph which depicts a young girl whom James seems to admire, calling her “quick-witted and full of fun.” She is weaving a basket, a fact that prompts James to remark how Havasupai mothers teach the art from a young age. He writes that the basket she holds “is crude and yet shows ability, and I gladly seemed [sic.] it and now have it in my home.” He goes on to describe her as “a bright and quick child and ‘smart’ also, in the American sense.”[20] He recalls her playful teasing and her confident manner. This jovial, familiar tone recurs throughout the descriptions accompanying James’ photographs of the Havasupai, showing a remarkably personal side to James’ relationship with those he encountered on his journey.[21] This outlook is maintained in The Indians of the Painted Desert Region. He reveals the young girl’s name, Pul-a-gas’-a-a, and again commends her skill: “If the child has patience to stick to it, in time she will become one of the most accomplished basket makers of the tribe.”[22]

Yet in his 1908 book, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, this same encounter is taken out of its context. Pul-a-gas’-a-a’s image is pasted into a chapter entitled, "The Indian and Physical Labor," where James explains that, in contrast to the white man, “the Indian really and truly believes in the dignity of physical labor.”[23] The picture serves an illustrative function as an example of an Indian engaging in work at a young age. The little girl he is so fond of goes unnamed, accompanied only by a general caption: “A Havasupai girl, weaver of baskets.”[24]

Why does James forgo Pul-a-gas’-a-a’s identity and his personal interaction with her in this instance? The answer lies in James’ purpose in writing What the White Race May Learn from the Indian. As the title suggests, the author intended to expound on what he views to be favorable aspects of Native American culture. He states at the outset of the text: “I call upon the white race to incorporate into its civilization the good things of the Indian civilization; to forsake the injurious things of its pseudo-civilized, artificial, and over-refined life, and to return to the simple, healthful, and natural life.”[25] It is at once a book of social criticism, an anthropological study, a manual for health, and a guide on morality. Furthermore, it was written for James’ primary audience: free-thinking Californians who were receptive to his commentary on modern society. The production and reproduction of the image of Pul-al-gas’-a-a thus illustrates the many ways in which James’ photographs functioned depending on the author’s intention.

I call upon the white race to incorporate into its civilization the good things of the Indian civilization; to forsake the injurious things of its pseudo-civilized, artificial, and over-refined life, and to return to the simple, healthful, and natural life.

What can we glean regarding James’ perceptions of the Indians he encountered from a look into the work he produced? Although the examples stated above provide evidence of a cordial relationship between James and the Havasupai he photographed, the former minister also shared some commonly held, harmful perspectives on indigenous peoples. For instance, in his book, Indian Basketry, James expresses the sentiment that Native Americans have not changed over time and are therefore primitive.[6] He states:

A few hundred years ago our own ancestors were "aborigines," - they wore skins for clothes, wove baskets…and depended upon the fortunes of the chase for their meats, just as the Amerind of the present and past generations are doing and have done. Hence, as Indian baskets are woven by human beings, akin to ourselves, and are used by them in a variety of relations of intensely human interest, we are studying humanity under its earliest and simplest phases…[27]

These ideas are reprehensible, and commonly invoked to provide evidence for white supremacist arguments. Furthermore, James’ accounts of his jovial and friendly interactions with the Havasupai should not be taken at face value. For one, the Indian voices are lost: no surviving comparable album or record exists from the Havasupai perspective, prohibiting confirmation of this cordial relationship. In addition, although not referring to the Havasupai specifically, an oral account casts a shadow of doubt on James’ trusting relationship with the Indians he met. A rancher stationed outside Grand Canyon National Park recalls his conversation with Chief Tawaquaptewa of the Hopi tribe: “I asked the Chief if Mr. James has ever asked for information regarding Hopi customs and was astounded when he told me that when Mr. James appeared, because of his long beard, they thought he was a chicka-wimpke (clown) and ‘when he asked funny questions they gave him funny answers.’”[28]

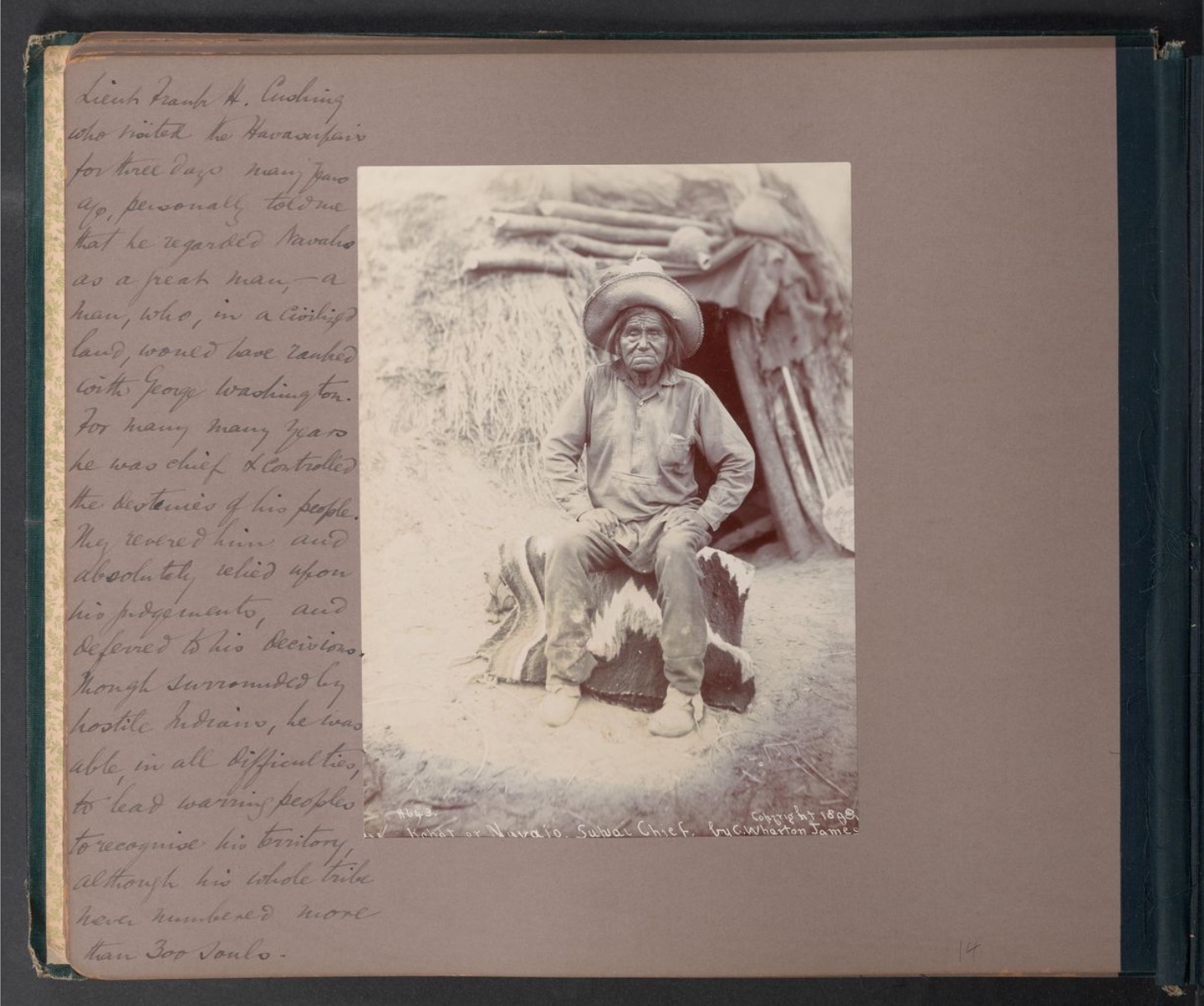

However, James’ other works show a different side of his perspective on Native peoples, one congruent with the warmhearted nature of the album. In his description of Kohot Navaho in The Indians of the Painted Desert Region, for instance, James says that the former chief had a character in which “firmness, courage, bravery, and gentle tenderness were commingled.” He continues on to commend his “dignity and pride.” In contrast to the pomposity of European monarchs, Navaho’s despotic power was “real”: “His kingship was within himself as well as in the affection of his people.[29] This sentiment is harmonious with Navaho’s presence in the 1900 album. In the text accompanying the chief’s image, James recounts the impressive reverence and success he garnered among the Havasupai: “They revered him and absolutely relied upon his judgements, and deferred to his decisions. Though surrounded by hostile Indians, he was able, in all difficulties, to lead warring peoples to recognize his territory, although his whole tribe never numbered more than 300 souls.”

They revered him and absolutely relied upon his judgements, and deferred to his decisions. Though surrounded by hostile Indians, he was able, in all difficulties, to lead warring peoples to recognize his territory, although his whole tribe never numbered more than 300 souls.

Furthermore, in his 1917 book, Arizona, the Wonderland, James debunks the idea that Indians are inherently violent, claiming that tribes will only resort to these measures if provoked by the white man. The author states further: “I have slept alone…in their camps…and have felt, and actually been, as secure as if I were in my bed in my own home.”[30] Moreover, James writes in What the White Race May Learn from the Indian that to steal Native lands under the guise of “benevolent assimilation” and “manifest destiny” is a conscious act of hypocrisy, one that the Indian, in “righteous indignation and wrath,” has risen up against. [31,32] He illustrates his claim with a quote from an Indian school child:

When we read in the United States history of white men fighting to defend their families, their homes, their corn-fields, their towns, and their hunting grounds, they are always called "patriots," and the children are urged to follow the examples of these brave, noble, and gallant men. But when Indians - our ancestors, and even our own parents - have fought to defend us and our homes, corn-fields, and hunting grounds they are called vindictive and merciless savages, bloody murderers...

Overall, James aims to lead his readers toward “a kinder and more honest attitude of mind towards the Indians,” condemning the despicable treatment of the Indian by the White man and contesting the notion of a “superior” race.[34] Although James may have shared some harmful views on Indigenous peoples, these examples show that he also sought to debunk other, equally harmful stereotypes held by the white population. His relationship with his subjects was thus complicated, defying categorization as totally positive or negative. Ultimately, James’ photographic album is a compelling object for historical study on multiple levels: it is valuable for its vernacular quality, its relation to the author’s life and travels, and the varied contemporary perceptions of indigenous populations.

[1] George Wharton James, What the White Race may Learn from the Indian (Forbes, 1908), p. 269.

[2] Wild, Peter. George Wharton James. Western Writers Series, No. 93. Boise: Boise State University Printing and Graphic Services, 1990, p. 14.

[3] Wild, pp. 11-15.

[4] Wild, p. 18.

[5] Wild, p. 18

[6] Wild, p. 17

[7] Wild, pp. 18-19.

[8] Wild, p. 18

[9] In his 1903 The Indians of the Painted Desert Region, James writes: "Here as I sit writing (September 14, 1901)," and proceeds to describe and Indian woman's process in making a basket. This statement implies that James did indeed take detailed notes during his travels which were directly incorporated into his later publications.

[10] Wild, p. 28.

[11] Wild, p. 28.

[12] Wild, p. 22.

[13] Wild, p. 22.

[14] Sandweiss, Martha A. Print the Legend: Photography and the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, p. 217.

[15] For evidence of this, compare the album annotations with a letter written and autographed by James which is being sold by Houle Rare Books & Autographs via Biblio.com. See https://www.biblio.com/book/autograph-letter-signed-james-george-wharton/d/1133383389

[16] Sandweiss, p. 215.

[17] Sandweiss, p. 215.

[18] James, George Wharton. The Indians of the Painted Desert Region: Hopis, Navahoes, Wallapais, Havasupais. United States: Little, Brown, 1903, p. 229.

[19] Sandweiss, p. 215.

[20] When I first read this quote, my immediate reaction was negative. I interpreted it as James emphasizing the difference he perceived between the Havasupai and White people, making Pul-a-gas'-a-a an exception. However, Professor Martha Sandweiss suggested that this statement could also be interpreted as James' recognition that different cultures have different values and definitions of the term. Upon delving further into James' works, I believe his intent aligns with the latter interpretation.

[21] Many of James' album annotations reveal fragments of conversations, compliments, and jokes between him and those he photographed. As stated in an earlier end note, there is evidence that suggests that James took extensive notes in the field which he incorporated into his works.

[22] James, The Indians of the Painted Desert Region, p. 227.

[23] James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, p. 105.

[24] James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, p. 106.

[25] James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, pp. 11-12.

[26] George Wharton James was the son of a basket maker. Accordingly, the Indian craft tradition became a prominent feature in his works. The topic proved to be central: James wrote a substantial volume entitled, Indian Basketry, on the subject, in which he expounds on the importance, history, and ceremonial and utilitarian function of weaving. He also explains various aspects of symbolism in basket designs and finally, how to make the baskets.

[27] James, Indian Basketry, p. 11.

[28] Quoted in Wild, p. 23.

[29] James, The Indians of the Painted Desert Region, pp. 230-231.

[30] James, Arizona, the Wonderland, p. 67.

[31] James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, p. 17.

[32] James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, p. 22.

[33] Quoted in James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, p. 25.

[34] James, What the White Race May Learn from the Indian, p. 12.

Works Cited

James, George Wharton. Arizona, the Wonderland. United States: Page Company, 1917. https://www.google.com/books/edition/ArizonatheWonderland/3t9CAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

James, George Wharton. Indian Basketry. United States: Privately printed by the author, 1903. https://www.google.com/books/edition/IndianBasketryandHowtoMakeIndian_a/Q7sRAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

James, George Wharton. The Havasupai Indians of Arizona Album. Princeton University Library Special Collections. https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/9999033323506421

James, George Wharton. The Indians of the Painted Desert Region: Hopis, Navahoes, Wallapais, Havasupais. United States: Little, Brown, 1903. https://www.google.com/books/edition/TheIndiansofthePaintedDesertRegion/R5YLAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&client=safari

James, George Wharton. What the White Race may Learn from the Indian. United States: Forbes, 1908. https://www.google.com/books/edition/WhattheWhiteRaceMayLearnfromtheI/b8SlOC4RWQEC?hl=en&gbpv=0&client=safari

Sandweiss, Martha A. Print the Legend: Photography and the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Wild, Peter. George Wharton James. Western Writers Series, No. 93. Boise: Boise State University Printing and Graphic Services, 1990.