Professor Sedgwick's Railway Extravaganza

By: Benjamin Bollinger '21

Access the digitized railroad guide and scrapbook via Princeton University Library.

On May 10th, 1869, a crowd gathered at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory to witness the final spike of the trans-continental railroad get hammered into place.[1] It was a moment made famous—or perhaps infamous—by the photographer Andrew J. Russell, whose portrait of the occasion (pictured above) you might recognize from a high school American history textbook. When we think of the railway, this image is what we see.

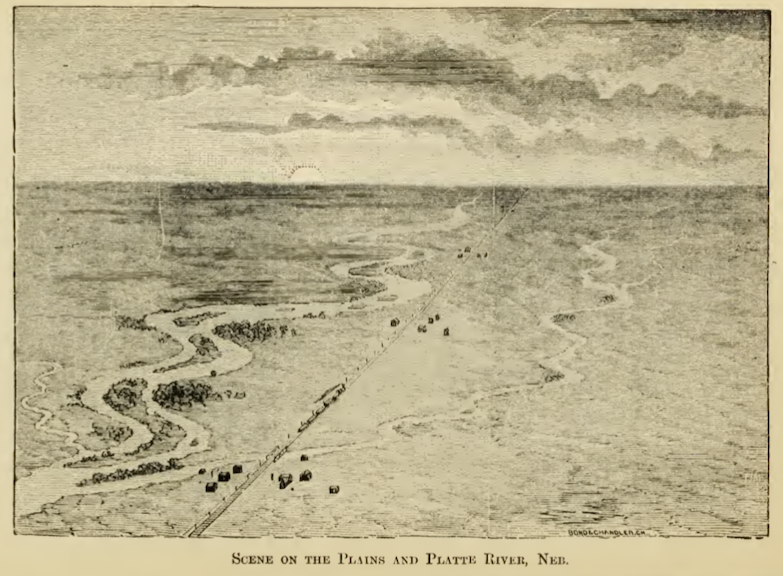

In fact, when we think of the railway, or the West in general, we “see” a lot of things: plains and mountains and forests and bridges and people with peculiar, outdoorsy hats. But that was not always so. Our visual memory of the West has been constructed with time, in fits and starts and sometimes all at once.

The completion of the trans-continental railroad was one such “at once.” Yes, before 1869, travelers still ogled and photographed the wonders of the West, but once the railway opened for business, these wonders became exposed to a new degree of ogling and photographing. It transformed America’s sense of scale: a once perilous, $1,000 journey could now be made safely for $150 and in a fraction of the time, making leisure travel of the West accessible to regular people.[2] Americans were increasingly curious to see, for themselves and through photographs, what the in-between bits of their nation looked like.

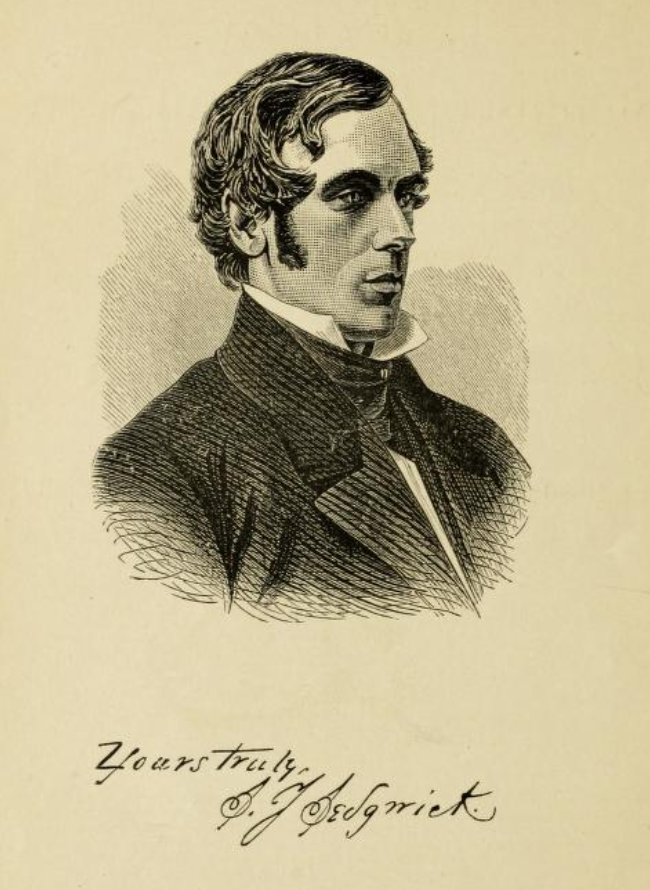

Enter Stephen James Sedgwick, railway enthusiast and traveling lecturer extraordinaire.

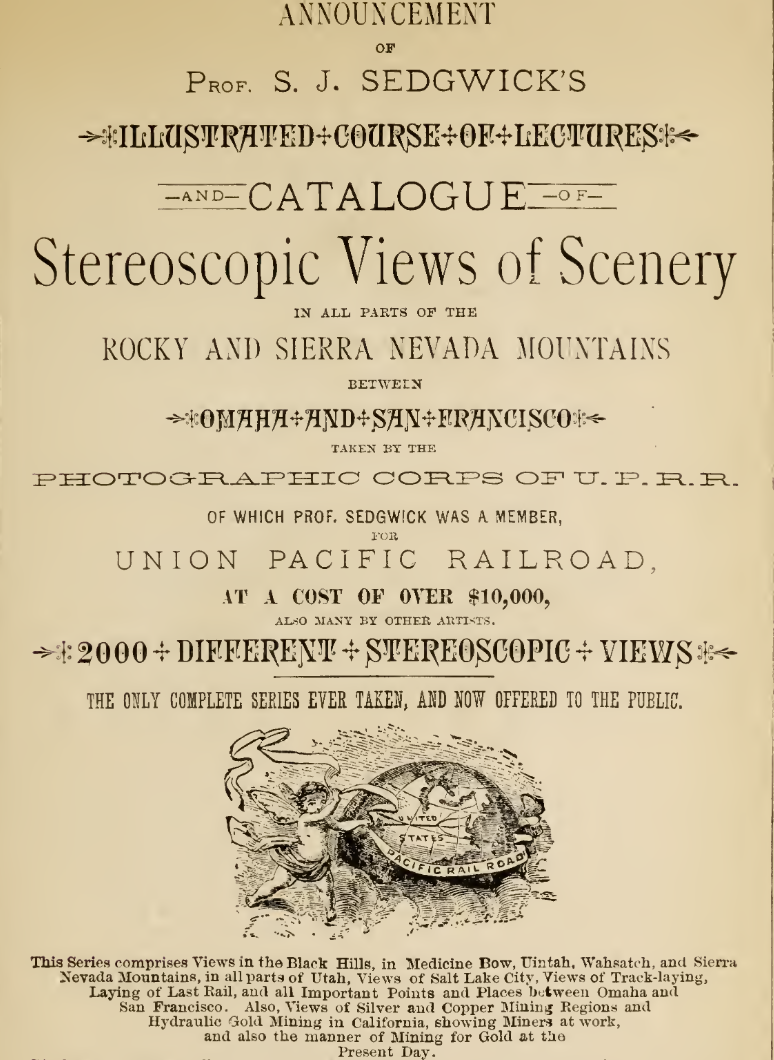

As a shameless promoter of his traveling lecture series, my guess is that Sedgwick would have been delighted by my sensational title for this article. The self-proclaimed “Professor Sedgwick” made several journeys westward along the trans-continental railroad in the years immediately following its completion—first as a photographer’s assistant to A.J. Russell (the same Russell as before) from 1869 to 1870, and later as a scout, salesman, and correspondent for the Chicago-based publisher George Croffutt in 1873.[3] Throughout his travels, he purchased and accumulated hundreds of glass-plate negatives, which he turned into slides that could be projected using a magic lantern device. These images formed the basis for his lectures about the American West.

We should pause to consider how this illustrated lecture format might have been received at the time. Put yourself in the shoes of a nineteenth-century audience member—without having visited each place yourself (remember, Google Images was not an option) how would you know what the railway looked like? Your understanding would be defined by paintings, photographs, and written accounts; a live commentary of projected slides is about the most immersive alternative you could hope for. So, when Sedgwick began delivering his lectures around 1873—whether in his home state of New York or at some stop along the railway itself—he was giving many people their first glimpse of Nebraska, the Rocky Mountains, the Uintas, Sacramento, and Utah.[4] He was defining their visual imagination of the West.

Wherever Prof. Sedgwick’s Photographs are shown, crowded houses must naturally follow.

Princeton’s Special Collections holds two relics of Professor Sedgwick’s railway travels. Or so I hope to convince you. While I can make a strong case that these materials document one or more of his westward trips, it's hard to say with pinpoint accuracy where they fall on his timeline, or what they might have been used for. They could readily apply to multiple parts of Sedgwick's life. That being said, I dusted off my trench coat and magnifying glass for some archival sleuthing, so I have my suspicions.

First, though, let's dive into the collection. Our primary item is an extensively annotated copy of George Crofutt's 1869 Great Trans-Continental Railroad Guide, the first of many editions that Crofutt would end up publishing.

Annotations aside, Crofutt's Guide is one of the first and most popular examples of an amusing genre of books: railway tourism. This copy is a hardcover book, roughly 8 by 5 inches, with 244 pages of information, advertisements, and empty leaves (presumably for journaling as you travelled, as they were used here). The Guide's extended title sheds some light on its intended use, since it claims, “In fact, to tell you what is worth seeing—where to see it—where to go—how to go—and whom to stop with while passing over the Union Pacific, Central Pacific Railroad of Cal,” including towns and cities, natural features of note, and “where to look for and hunt the Buffalo, Antelope, and other game.” This title shows us some of the leisure activities Americans were interested in (like hunting), but more importantly, it highlights the railway as the unifying theme of sightseeing.

Travelers would have most likely purchased Crofutt's Guide while riding the train. At this period, train stations and trains themselves were actually the main outlets for recreational railway reading.[5] Librarian Thomas Kilton even singles out Crofutt's 1869 Guide as a particularly "important early hardcover book... that was sold by news agents on the early transcontinental trains operated by the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads."[6] Passengers could buy the book on the train and follow its recommendations as they rode westward. It was organized by railroad station from east to west, making the travel tips easy to follow.

The Beaver is very shy, and although you often hear them plunge into the water, you must be extremely patient and cautious if you would see them work. Their dams are sometimes 6 ft in height.

And that is exactly what someone, maybe Sedgwick, appears to have done, judging from the mysterious handwritten entries and annotations throughout the book. They seem to document a traveler's journey west along the railroad—a typical entry reads, "From N. Platte to Sidney is 123 miles. We pass 10 stations. The rise is from 2789 ft. to 4073 ft., or 1284 ft, or a fraction over 10 ft to the mile. Average distance of stations over 12 miles," followed by a meticulous list of railway stations and the distances between them. The annotator careened from detailed information about distance and altitude (frequently correcting the text of Crofutt’s Guide) to more personal anecdotes about everything from geography, to indigenous people, to the beavers of Lodge Pole Creek. What’s more, they pasted in numerous woodcut illustrations to embellish their guidebook.

Yet, at no point does the author give us a signature. Stranger still, none of the entries of supposed travel are dated, and the author does not mention encountering any other people on their journey. Why would someone taking such detailed notes about something like altitude fail to mention even one date of departure or arrival?

The mystery deepens with our second item, an untitled scrapbook containing snippets of Crofutt’s 1869 Guide.

This scrapbook leaves us even fewer crumbs to taste. Much larger than the guidebook at about 24 by 12 inches, it has no markings on the outside. Inside, it is roughly half full with scrapbook clippings from Crofutt’s 1869 Guide (but not taken from our annotated copy), sections of Froiseth's 1871 "New Sectional & Mineral Map of Utah," Utah-related news articles, photographs, prints, and a few more maps in a small envelope attached to the back cover. That means that these clippings can be no earlier than 1869 and 1871, but it gives us little information about who pasted them in and when they did so.

Who did these items belong to, and what were they being used for? It's time to put on your detective hat.

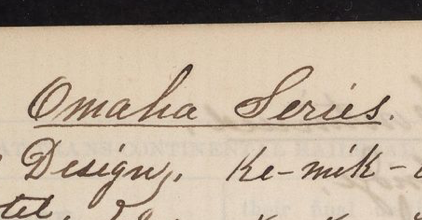

Our first clue comes in the form of the black-inked "S.J. Sedgwick" stamps scattered throughout the guidebook. These stamps appear in notable places of the book, like the title page and (as above) alongside some of the handwritten entries, suggesting that this copy at least lived in Sedgwick's library at some point. The stamp alone, though, does not prove that Sedgwick who the one who wrote the journal entries—after all, he was a prolific compiler of other people's photographs, like those of his traveling partner A.J. Russell. Yet, by comparing this guidebook’s handwriting to that in the S.J. Sedgwick collection at Yale University, we see that there is a clear match.[7] Note for yourself the distinctive inward curl of the "O" in "Omaha" for each of the above samples.

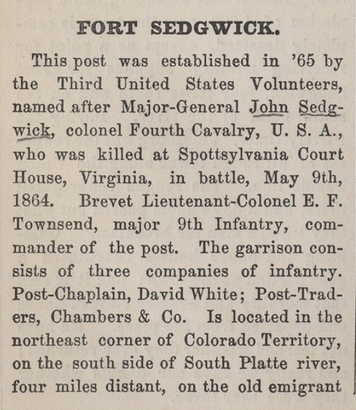

Our detective ears should also prick up at the topics that drew the attention of our mystery annotator. First and foremost is the topic of chief interest to any person, but especially so for Sedgwick the salesman: himself. We see the name "John Sedgwick" underlined out of the blue in a section of the guidebook on Fort Sedgwick—I found no relation between S.J. and John Sedgwick on Ancestry.com, but this incidental marking still tells us more about the annotator than he might have realized at the time.[8]

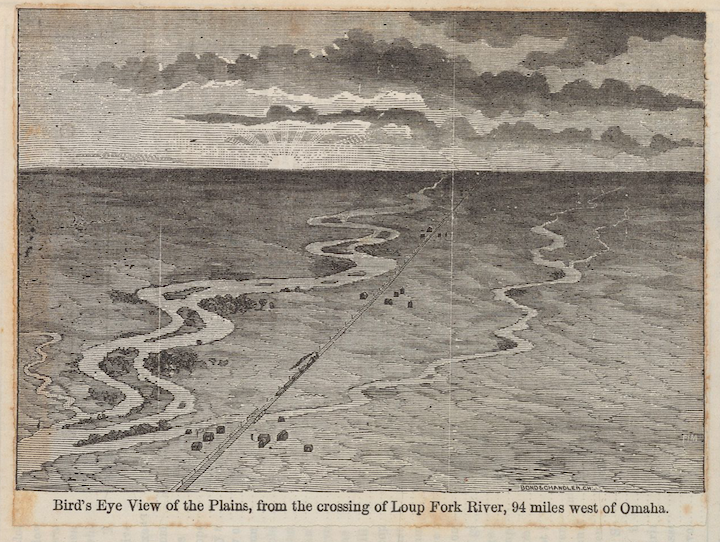

More broadly, though, the handwritten entries in this guidebook are remarkably consistent with those in the S.J. Sedgwick collection at Yale University. The notes in Yale’s collection document Sedgwick’s 1873 trip west as a representative of George Crofutt’s railway publishing empire. En route to Grand Island in 1873, Sedgwick writes that, “After leaving Columbus, the R.R. sped away nearly S.W. following along the north bank of the Platte R., which it keeps in sight—most of the way. The country is level, and the grade from 6 to 7 ft per mile.”[9] This attention to direction and grading is equally present in the entries of Princeton's guidebook: “Leaving Omaha… along the Bank of the River, + there turn to the W’d, which henceforth is our general bearing, although in making it we traverse nearly every point of the compass... an ascending grade of a fraction over 5ft to the mile.” Indeed, these are two notes about the exact same stretch of Nebraskan track.

Why do I lack the feeling that we're going anywhere?

The style and content of writing in Princeton's guidebook scream Sedgwick. Yet, the comparison to Yale's collection raises the same question as before—why is there no mention of travel dates or companions? Sedgwick compulsively records the details of his 1873 trip in the Yale scrapbook: "Left Omaha Friday July 25th at 7:30 - Arrive at Columbus at 5 O’Clock, stop at Hammond House - John Hammond."[10] The most we get in this guidebook is a passing reference to Harper's Magazine in 1871, or a pasted-in illustration of the officers of the Union Pacific Railroad Company in 1871. Why do I lack the feeling that we're going anywhere?

Because, in my amateur, trench-coated opinion, Sedgwick is not taking us on a specific railway journey in this guidebook. Instead, these handwritten entries represent the compiled notes of his previous journeys westward, arranged and curated by Sedgwick as a loose script for his illustrated lecture series.

Grab your magnifying glass and take a look at this handwritten guidebook entry, entitled "Omaha Series." Sedgwick lists a series of photographic views, ranging from Nebraska's "Omaha S.E. from Cald." to Wyoming's "Dale Creek Bridge." Many of these names match up exactly with those of photographs taken by Russell—that makes sense, given Sedgwick travelled as Russell's photographic assistant in 1869 and purchased some of his views for the illustrated lectures.[11] But curiously, the first three images are bracketed as "Introd.," suggesting that they serve as a visual introduction to some kind of presentation. Many of their names also line up a little too exactly with the final ones issued by Russell, which undermines the idea that this was a functional list made at the moment the photographs were being taken.[12] And finally, none of the images are listed with their assigned glass-plate negative number, which hints that Sedgwick may have compiled this list for the purpose of presentation as opposed to record-keeping.

I was able to identify several likely examples of Russell's photography in Sedgwick's "Omaha Series" entry, alone.

These included "Hotel at Laramie" (above), in addition to "Machine Shops S. Look W.," "Cor. of Douglas + 15th S.," "Capital," "Cars Exterior, Interior, and Sleeping," "Loup R. Bridge, ex.," and a personal favorite, "Antelope group." [14] Half or more of the photographs on this list appear to be Russell's doing. The same is true of lists that appear throughout the guidebook for Echo Park, Weber Canyon, Uintah, Yosemite, and more.

To see is not always to observe.

But there is more that leads me to believe that this guidebook is Sedgwick's lecture script or draft, and not his journal. William D. Pattison's secondhand study of Sedgwick's lectures bears an eerie resemblance to the language and structure of this guidebook. Pattison remarks, for one, that in his series on the Rocky Mountains, "Sedgwick's interest in geology came to the fore"—at each show, he would project photographs of exposed rock formations and "repeat an admonition of the great German traveler, Alexander von Humboldt, 'To see is not always to observe.'"[14] The same pattern occurs in this guidebook, when Sedgwick writes that Wyoming is "to the Geologist one of the most fruitful of regions, confirming the observation of Humboldt, that 'to see is not always to observe.'"

Pattison further writes that Sedgwick liked to include "notes on the distance between stations, the rate of ascent up the long slope of the plains," and other miscellany on wells, bridges, and fossils.[15] There are entries on all of these topics in the guidebook, like this one on the fossil deposits of the Black Hills:

Sedgwick would have regaled his audience with fantastic tales of scientific wonder. In this entry, which references an 1871 article in Harper's Magazine, it happens to be "the oreodon, a remarkable animal combining characteristics of the modern sheep, pig, and deer" and "the Titanotherium, a monster of such vast proportions that a lower jaw measured over four feet in length."[16] Anecdotes like these were accumulated by Sedgwick over time, making this guidebook the imagined, compiled narrative of many trips, instead of the real account of one single trip.

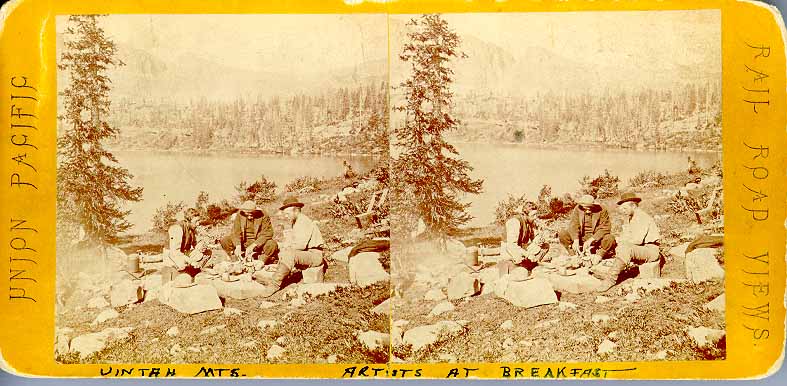

Pattison's account also confirms something we already knew—that Sedgwick liked to made himself the star of the show. He enjoyed, for instance, going out of his way to talk about "a sojourn of several weeks in the Uintas taken by Union Pacific photographers in the summer of 1869," a group that included both himself and A.J. Russell.[17] The photographs referenced by Pattison are likewise included in the "Uintah Series" entry of the guidebook:

Here we meet Sedgwick and his band of fellow artists once again—both "Breakfast" and "Photographing under difficulties" are mentioned in the guidebook. Sedgwick even handwrites additional information about their Uintah excursion, like the date of "Party snow, W. Pines" as "Aug. 1," which is a fact that would not have been included on the published stereograph. Of course, he really did visit these places to gather data and images. But when we read the annotated entries of this guidebook, we are reading an imagined travel narrative, one that Sedgwick constructed and performed at a later date for his lecture audience.

So, let's take a final moment to imagine. The room is full and Sedgwick stands behind his magic lantern device, ready to project. Pattison writes that he liked to open the lecture with "an extended prologue in praise of the Union Pacific"—and that is exactly how the guidebook entries begin.[18] We can imagine Sedgwick reading aloud:

"'Westward the Star of Empire takes its way,' said Bishop Berkeley 140 years ago. A sentence so often quoted that it has passed into a household word, and placed its author high on the list of memorable names."

Perhaps Sedgwick flips to his first magic lantern slide:

"But, where is Westward asks the thinker of today? 40 years ago it was the fertile and vast plains of S. + W. of the great lakes + E. of the Mississippi R. All beyond that was a blank—the home of the Indian + the wild beast."

No longer, though, as Sedgwick would prove. The West could now be condensed into an hour and a half session of exciting visuals and lively commentary. His lectures gave viewers an immersive journey from the plains of Nebraska to the Uintah Mountains, and more—all following the route of the Trans-Continental Railroad. They could see everything from natural formations like "that great curiosity on the summit of the Black Hills, now known as Red’s Rock,'" to wild creatures like the Antelope, which "is to be seen in great numbers, bounding over the bottoms towards the hills as the cars pass along" the Lodge Pole Creek Valley. For a price.

In this sense, the guidebook and scrapbook in Princeton's collections are curious relics of Sedgwick's imagined journey. Of course, we cannot rule out entirely the possibility that Sedgwick wrote his journal entries on the trail with A.J. Russell in 1869, but I believe that a host of evidence—from the handwritten lists of photographic views to Pattison's indirect descriptions of Sedgwick's early 1870s lectures—suggests that they came later, perhaps copied and edited from other notes. Sedgwick may have even held it in his hands while presenting his magic lantern extravaganza.

As Sedgwick loved to quote, "To see is not always to observe." The completion of the trans-continental railroad in 1869 opened the American West to observation like never before. But it did not eliminate the desire to see. As a rail traveler, but also an entertainer, Sedgwick sat in a unique position between the West as a physical and imagined place. By opening his viewers' eyes to its grandeur—mountains and bridges and valleys—he helped shape a visual idea of the West that lives on in collective memory to this day.

[1] "Andrew J. Russell." National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/gosp/learn/historyculture/a-moment-in-time.htm.

[2] “Transcontinental Railroad.” History.com. Last updated September 11, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/transcontinental-railroad.

[3] Sandweiss, Martha. Print the Legend: Photography and the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. S. J. Sedgwick Collection. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/11366.

[4] Pattison, William D. "Westward by Rail with Professor Sedgwick: A Lantern Journey of 1873," The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly (1960) 42 (4): 335–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/41169486.

[5] Kilton, Tom D. “The American Railroad as Publisher, Bookseller, and Librarian.” The Journal of Library History (1974-1987), Winter 1982, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 39-64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25541236.

[6] Ibid.

[7] S. J. Sedgwick Collection. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/11366.

[8] "Stephen James Sedgwick (1820-1920)." Ancestry.com

[9] S. J. Sedgwick Collection. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/11366.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Winter, Rebecca Cooper. "ANDREW J. RUSSELL STEREOGRAPH CATALOG." Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum. http://cprr.org/Museum/Russell_Catalog.html.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Pattison, William D. "Westward by Rail with Professor Sedgwick: A Lantern Journey of 1873," The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly (1960) 42 (4): 335–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/41169486.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Harper’s Weekly.” Vol. 5. New York: Harper's Magazine Co., etc., 1871. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000061498.

[17] Pattison, William D. "Westward by Rail with Professor Sedgwick: A Lantern Journey of 1873," The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly (1960) 42 (4): 335–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/41169486.

[18] Ibid.