Depicting the Great Work

The Ripley Scroll represents an early attempt to encapsulate the entire alchemical work within a single iconographic scheme. Print created new opportunities for spectacular and intricate designs, in the form of engravings that sometimes occupied an entire page. Besides detailing individual processes, 17th-century engravings expressed broader relationships between art and nature, prayer and practice, and heaven and earth. Such universalizing schemes were not unique to alchemy, but were also employed by scholarly authors to visualize broader cosmologies and systems of natural knowledge, from the interior of the earth to the moment of Creation.

Heinrich Khunrath (1560-1605). Amphitheatrum sapientiae aeternae, solius verae, christiano-kabalisticum, divino-magicum, nec non physico-chymicum …, 1609 (Hanover: Guillielmus Antonius)

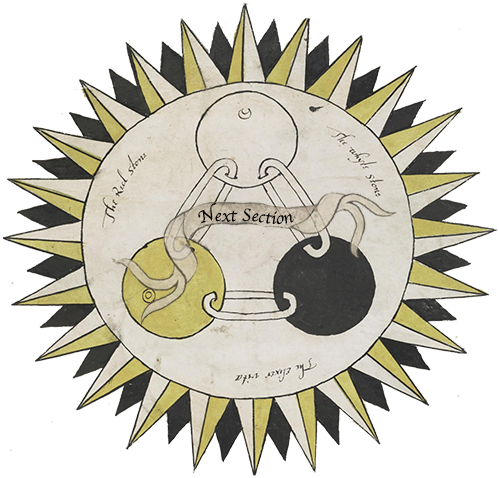

Physical chemistry melds with Christian Cabala and divine magic in the Amphitheater of Eternal Wisdom, written by the Paracelsian physician and alchemist Heinrich Khunrath. The relationship between the divine, supernatural, and natural realms is captured in a series of elaborate, circular engravings — most famously, in Khunrath’s double-plate engraving of the “Oratory/Laboratory.” On the left-hand side, the alchemist prays in the oratory, the realm of God. On the right, a well-equipped laboratory represents the realm of Nature.

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), Mundus subterraneus, in XII libros digestus, 1655 (Amsterdam: Joannes Jansson and Elizeus Weyerstraet

Rare Books Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

In 1638, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher gazed into the crater of Mount Vesuvius. Years later, in the Underground World, he posited a network of fiery, subterranean reservoirs that fueled volcanic eruptions. Drawing on medieval theories, he proposed that volcanic heat helped to form the metals from two primordial principles, “Sulphur” and “Mercury.” In a process akin to fractional distillation, underground chambers (labeled C to G) capture the principles in varying proportions, forming different metals and minerals.

Robert Fludd (1574-1637), Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia, vol. 1, 1617(Oppenheim, Germany: Theodore deBry)

Rare Books Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

The cosmos, with Earth (represented by the Garden of Eden) at the center. Throughout the two-volume History of the Macrocosm and Microcosm, the physician Robert Fludd used exquisite, geometrical diagrams to explore correspondences between the “double world” of macrocosm (the cosmos) and microcosm (humanity). His elaborate cosmology drew on the philosophy of Neoplatonism and the writings of Paracelsus, who envisaged the moment of Creation as a chemical separation on a cosmic scale.

Robert Fludd (1574-1637), Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia, vol. 2, 1618 (Oppenheim, Germany: Theodore deBry)

Rare Books Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

### In this plate, Fludd illustrates the routes by which the human mind can access three worlds of knowledge: sensible, imaginable, and intellectual. While the physical world is known through the five senses, more abstract concepts are constructed in the imagination, while still drawing on information from the senses. Knowledge of the divine—the world of God and the hierarchy of angels—is apprehended by the mind directly, through reason and intellect.

Robert Fludd (1574-1637), Philosophia Moysaica, 1638 (Gouda, Netherlands: Petrus Rammazenius)

Rare Books Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library