The Chemical Wedding

The second panel of the Ripley Scroll depicts the manufacture of the philosophers’ stone as a double fountain populated by human figures. It includes many conventional elements of medieval alchemical imagery. Above, the “chemical wedding” of Sun and Moon signifies both the chemical combination of two substances, and the philosophical union of two sets of contrary principles: the heat and dryness of the sun, with the coolness and moisture of the moon. Below, three figures represent the division of the stone into body, soul, and spirit

Abū Yaḥyā Zakariyyā al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283), ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat wa-ghara’ib al-mawjudat, 18th century

Gift of Robert Garrett, 1942, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Human personifications of the planets were common across disciplines. This illustrated encyclopedia, the Wonder of Creation, written by the astronomer al-Qazwīnī, was widely read in the Islamic world. Here, the planets are represented as human figures: Mercury (on the right) writes in a book, while Venus (on the left) plays a musical instrument. Although al-Qazwīnī wrote about alchemy, he seems to have rejected alchemists’ claims to transmute base metals into gold.

Domenico Beccafumi (1484-1551), The Barber, ca. 1525-40 (left) and The Blacksmith, ca. 1525-40 (right)

Woodcuts from the series La ricera e lo sfruttamento dei metalli (Itally)

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Leo Steinberg

Each of the seven “canonical” metals has its planetary equivalent in alchemical and metallurgical writings: gold (Sun), silver (Moon), quicksilver (Mercury), copper (Venus), iron (Mars), tin (Jupiter), and lead (Saturn). In Beccafumi’s series of woodcuts, the planetary deities are used to depict the metals, as they are mined from the earth and worked by human artisans. They are dragged in chains to the anvil, led by Saturn, whose age and lameness suggest the corruptibility of lead. Quicksilver, both liquid and volatile, appears as the winged messenger Mercury.

Gold, silver

Modern Samples

Courtesy of Lawrence M. Principe

In medieval alchemical theory, quicksilver often provided the basic ingredient for the stone. Small quantities of the precious metals, gold and silver, were necessary to complete the work, through a process known as fermentation. In alchemical imagery, this process is commonly depicted as the wedding of Sun and Moon, mediated by Mercury.

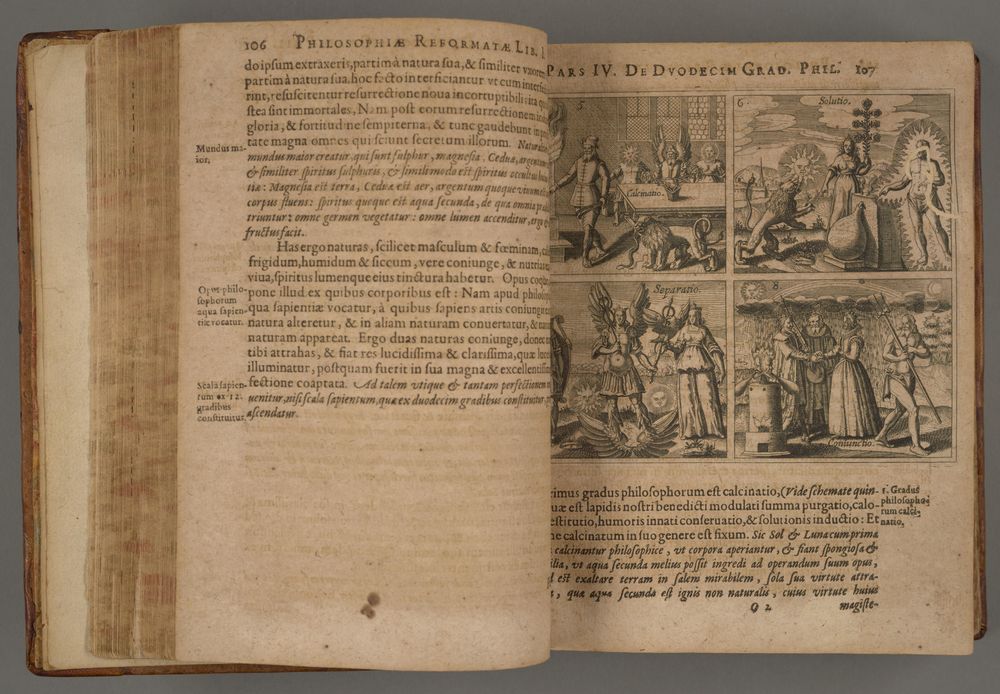

Johann Daniel Mylius (1585–1642), Philosophia reformata, continent libros binos, 1622 (Frankfurt am Main: Lucas Jennis)

Copperplate illustrations by Matthaeus Merian

Rare Books Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

The physician Johann Daniel Mylius illustrated his edition of the 15th-century Scala philosophorum (Ladder of the Philosophers) with twelve alchemical engravings, including the Chemical Wedding. The sequence shown here was originally designed for a later work, the Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine, which describes a different chemical approach, based on antimony. Mylius has retrofitted the sequence by adding titles that correspond to the first four steps of the Scala: Calcination, Dissolution, Separation, and Conjunction.

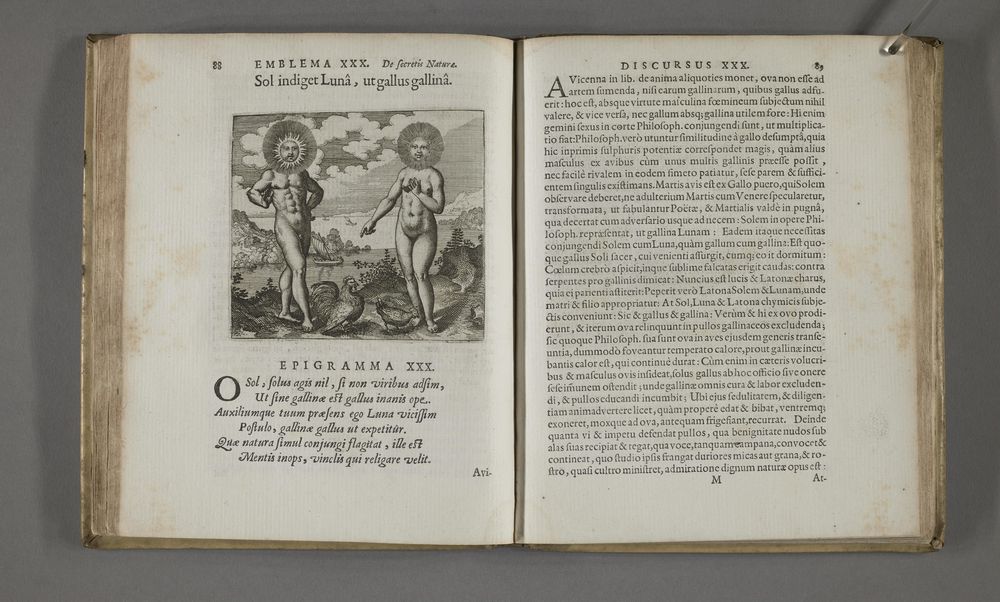

Michael Maier (1568? –1622), Secretioris naturae secretorum scrutinium chymicum per oculis et intelectui, 1687 (Frankfurt am Main: Johann Philipp Andreus for Georg Heinrich Oehringius)

Rare Books Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

German alchemist Michael Maier published a series of fifty alchemical emblems in his Atalanta fugiens (1617), here in a later edition. Maier recycled designs from earlier sources, including his depiction of the Chemical Wedding, adapted from a famous 14th-century Bildegedicht (“picture-poem”). The Moon warns her husband in the accompanying motto that “The Sun needs the Moon, as the cock needs the hen.” Two parents — or chemical substances — are required to generate the philosophical child.

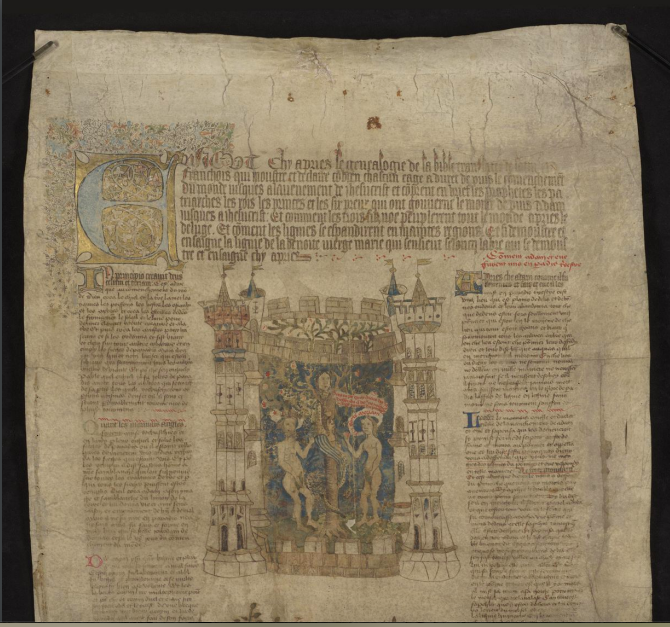

Chronique universelle (1440s–50s), Northern France or Belgium (Picardy, Artois, or French Flanders)

Manuscript roll on vellum

Cotsen Children’s Library, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library