Stamps & Seals

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Le rovine del Castello dell’Acqua Giulia. Rome, 1761

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

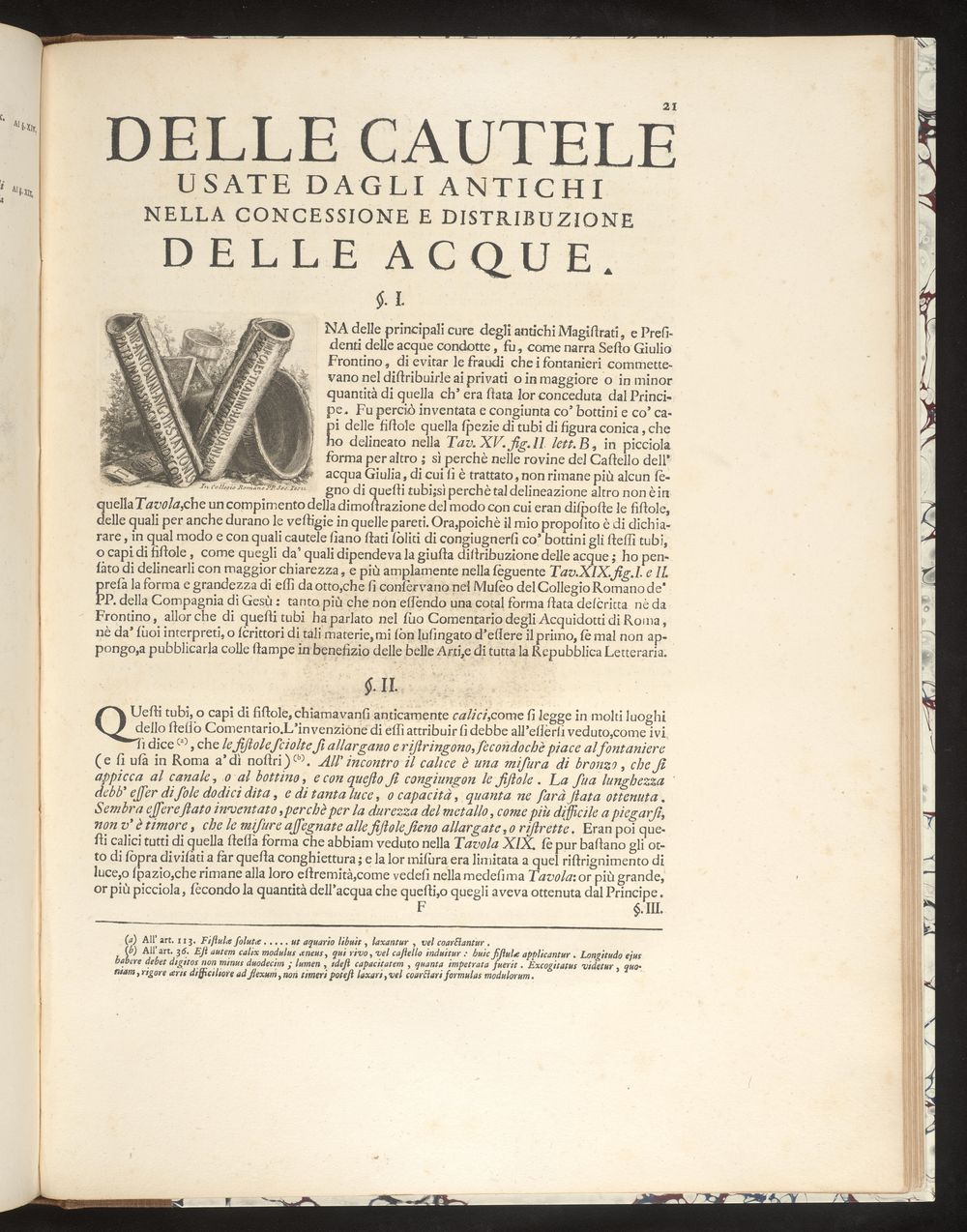

Piranesi designed text and image to complement each other. When he made prints for the blank spaces of his letterpress pages, he emphasized the objects in his arguments. Le rovine del Castello dell’Acqua Giulia describes the Roman aqueduct system. The book includes discussion of a passage from Frontinus, a first-century Roman civil engineer. Piranesi’s vignette features various mechanisms of Rome’s water supply that Frontinus had explained. The supply depended on an elaborate system of lead pipes, two of which form the initial letter V in the vignette. Behind the pipes, Piranesi depicts the bronze cups that connected these pipes to houses.

Fragment of a lead pipe with an inscription, discovered near the Palatine Hill, Rome

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Dan Fellows Platt

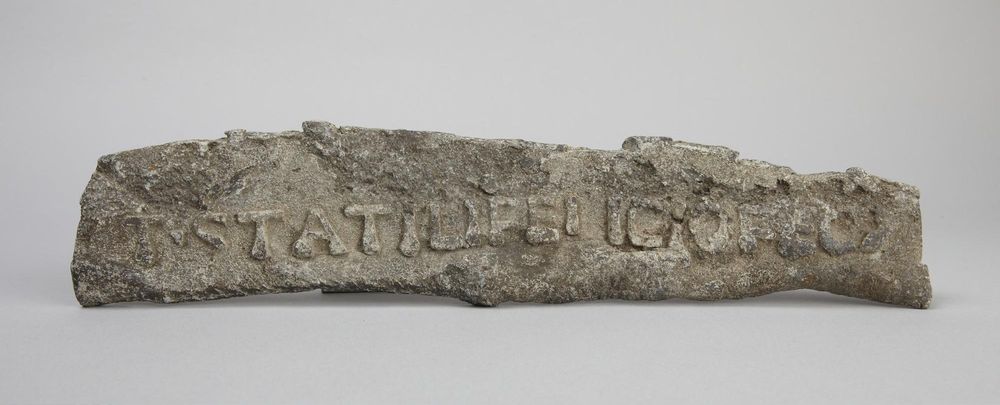

Piranesi’s interest in Roman pipes went beyond their hydraulic functions. Lead pipes are another example of an ancient writing method, because many of them have the name of the manufacturer or owner visible in high-relief letters. To make the pipes, flat sheets of lead were folded into cylinders and soldered to form tubes. Full-text stamps of names written in reverse were impressed into the moulds used to make the sheets. When lead was poured into these moulds, the names on the resulting sheet could be read from left to right in raised letters. The process is a means of forming words through casting, which differentiates it from both intaglio printing and movable type. This pipe has the name of its manufacturer written on its side: T.STATILI FELICIO FEC. Other pipes, like those depicted by Piranesi, had the names of emperors, the de facto owners of the entire water supply system.

Bronze Stamp

Princeton University Art Museum

Objects with cast, impressed, and carved texts abounded in the ancient world. A signaculum--literally, a seal--was a cast metal device that often had reversed letters, and could be used to stamp a variety of things from roof tiles to amphorae to soldiers’ identification tags. It seems natural that Piranesi, who relied on cast metal fonts to make the letterpress pages in his books, was attracted to these artifacts. This signaculum may have been used to impress bread dough before baking. A printing matrix can be used on just about anything.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Della Magnificenza ed architettura de' Romani. Rome, 1761

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

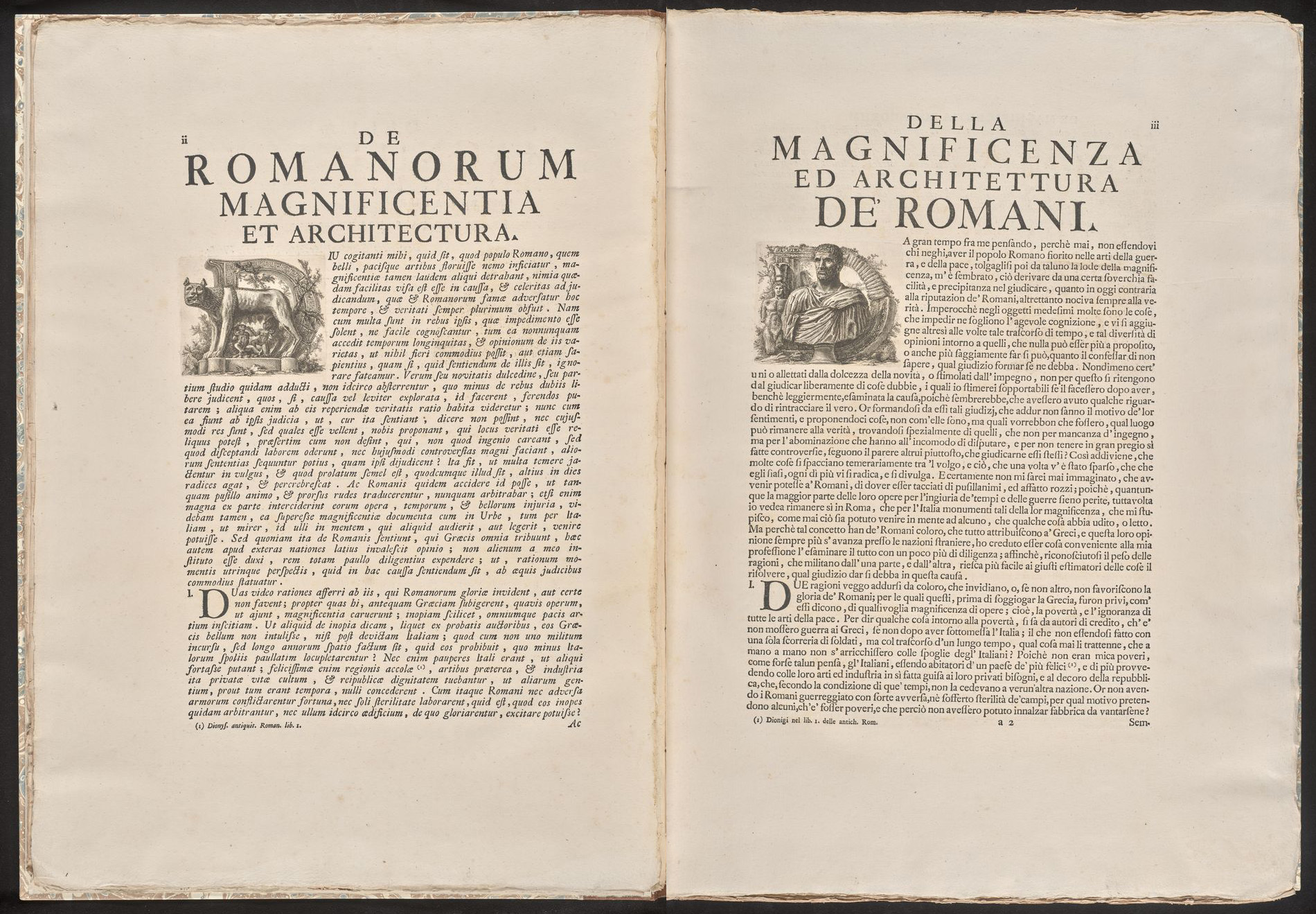

These two vignettes feature iconic sculptures associated with Rome’s origins. Piranesi designed them to illustrate his sprawling essay that extolls the city’s ancient architecture. He would have seen both sculptures displayed among the collections installed on the Capitoline Hill. On the left, the twins Romulus and Remus suckle at the she-wolf; they will go on to found the city of Rome. During Piranesi’s day, the bust on the right was thought to depict Lucius Junius Brutus (d. 509 BCE), one of the first consuls of the republic who had overthrown the city’s last king. In these side-by-side vignettes, Piranesi juxtaposes myth and history as evoked by art.

Terracotta fragment of a stamped Roman brick

Princeton University Art Museum

Brick stamps combined Piranesi’s interests in writing and architecture into a single historical object. Ancient bricks were often impressed with the names of the owner of the brickyard and the current consuls. This brick reads: [...] XAM [...] MINORIBOPD [...] EX PR DOMITIAE LVCIL [...]. It was manufactured by Domitia Lucilla the Younger (d. 155–161), mother of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. She was part of a dynasty of brickmakers who launched their business around 39 CE. Bricks from her factory, which she inherited from her mother, were used to build the Pantheon and the Colosseum.

Seals

Engraved gems carved from precious stones fascinated Piranesi. Gems often were impressed in hot wax to create their mirror images, both in antiquity and in Piranesi’s day. In the eighteenth century, a debate continued over whether this practice constituted an ancient form of printing. Piranesi incorporated symbols like the ones on these examples into his designs for reliefs. The red jasper gem in particular is the type of object that he appreciated: incised on one side with raised relief on the other, the gem is Etruscan. It thus derives from an ancient culture that Piranesi championed as the ancestor of Rome.

Engraved amethyst gem with Romulus and Remus and the wolf, Roman

Princeton University Art Museum

Engraved carnelian gem with a caduceus and cornucopiae, Roman

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Ario Pardee

Two-sided red jasper gem with a bird and scarab, Etruscan

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Frank Jewett Mather, Jr.