Settling Scores

Piranesi used publishing to settle scores. Piranesi’s Lettere di giustificazione scritte a milord Charlemont e à di lui agenti di Roma dal signor Piranesi is an angry screed, a calculated publicity ploy, and a meditation on the power of the printed word. Above all, the short pamphlet demonstrates how the author’s deep concern for the reception of his books affected the work that he made. In the 1750s, when Piranesi was preparing what would become his four-volume Antichità Romane, he sought the support of a patron to help finance the work. James Caulfeild, Earl of Charlemont, pledged his support for the book. After Piranesi’s project swelled beyond its original scope, Charlemont never delivered the promised funds. In revenge, Piranesi published a highly edited version of correspondence he had exchanged with Charlemont’s agents as the Lettere di giustificazione in 1757, accusing them and their boss of deceitful dealings.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Lettere di giustificazione scritte a milord Charlemont e a’ di lui agenti di Roma dal signor Piranesi, 1757

Image used for online component: Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University Library

In its story of communication gone haywire, the Lettere di giustificazione conveys how even ephemeral acts of writing can have severe consequences when made public. Borrowing from the eighteenth-century genre of the epistolary novel, the short book emphasizes the written word as a medium with legally binding and socially powerful consequences--in this case, for Piranesi and his failed patron. On its title page, the book’s name appears as if inscribed on a broken obelisk: a reference to Piranesi’s interest in both stone inscriptions and ancient Egyptian art as vehicles to preserve words over vast periods of time. Later prints in the Lettere show how Piranesi had erased Lord Charlemont’s name from the dedication plates of the Antichità Romane.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Lettere di giustificazione scritte a milord Charlemont e a’ di lui agenti di Roma dal signor Piranesi, 1757

Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University Library

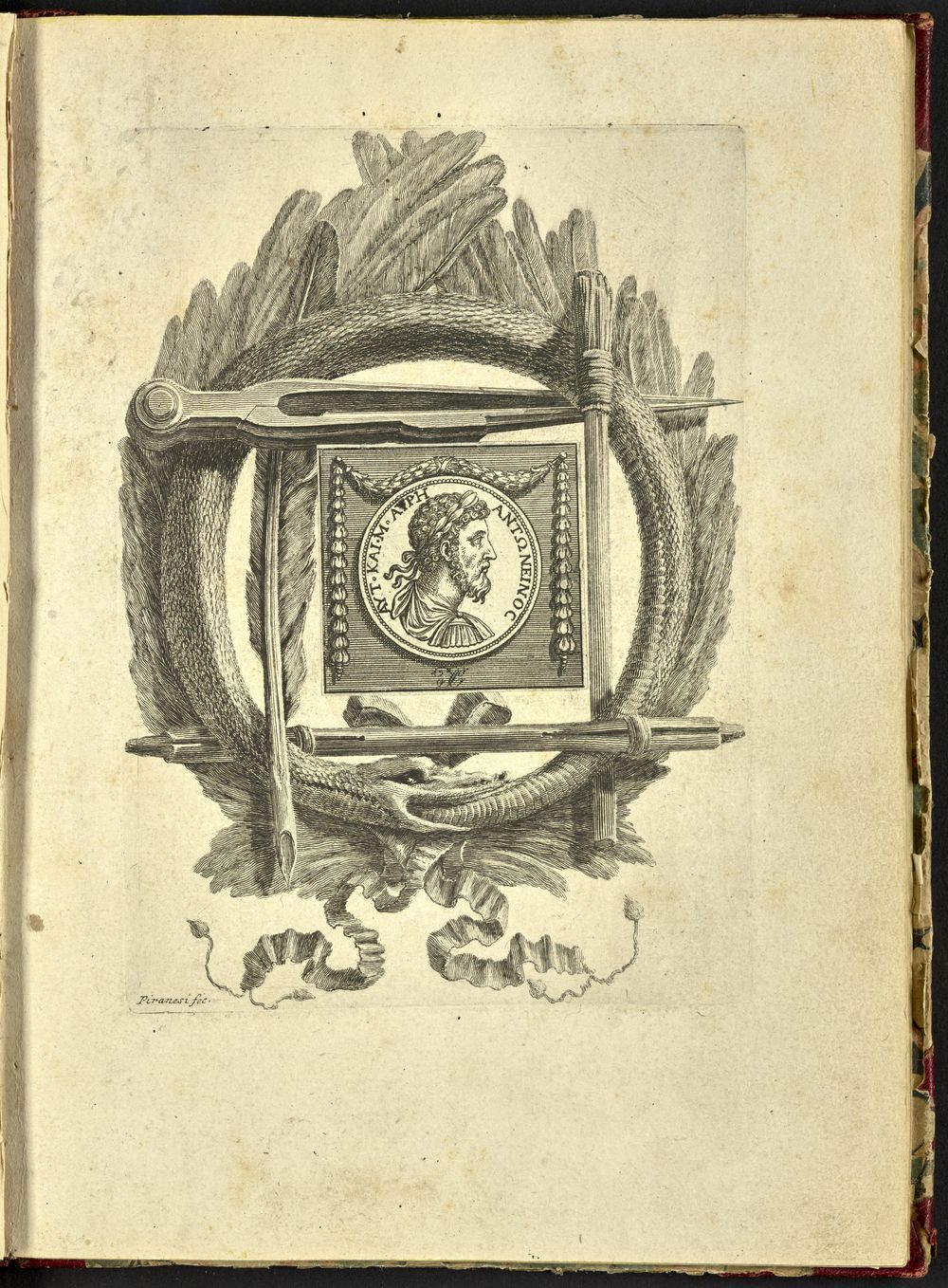

Piranesi opened the Lettere with an autobiographical vignette. The etching features the artist’s tools arranged into a frame: dividers, brush, stylus or porte-crayon, and quill pen. The instruments hold in place an ouroboros, or serpent that devours its own tail, as a reference to eternity. Piranesi addressed his readers by inscribing their names at the printer’s center. In Princeton's copy of the Lettere, a later owner has obscured the original recipient's name with a small print from a numismatic book.

Limestone cartouche of Hatshepsut, New Kingdom, Egypt

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of William C. Hayes, Class of 1924

Carved hieroglyphs are an art of low relief. This aspect of ancient Egyptian art was not lost on Piranesi, who treated his copperplates as a form of thin sculpture. Although he never traveled to Egypt, Piranesi referred to its monuments frequently in his work, as in the Lettere’s title page. This cartouche of Hatshepsut, Queen of Egypt, suggests why hieroglyphs in particular fascinated Piranesi. In the inscription, which gives the ruler’s name and title, carved words convey specific information and also function as pictorial symbols. Piranesi, who could not understand hieroglyphs as language, nevertheless admired them as a means to make images function as texts.

Hematite gnostic gem with an ouroboros encircling four figures, with its impression

Princeton University Art Museum, The Collection of Virginia Aldrich Van Vleck, Gift of Joseph Van Vleck, Jr., Class of 1923

In his dedicatory vignette, Piranesi ensnared the ouroboros within his own image-making tools and launched the Lettere’s argument. The snake that bites its own tail simultaneously evokes the cyclical nature of time as well as the patron who, through his actions, succeeds only in harming himself. The symbol of the ouroboros derives from ancient Egyptian iconography; it also has alchemical associations. It frequently appears on gnostic gems like this one as an inscribed frame.