Coins & Medallions

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Tailpiece to the "Della introduzione e del progresso delle belle arti in Europa ne' tempi antichi," printed with the Osservazioni di Gio. Battista Piranesi sopra la Lettre de M. Mariette aux auteurs de la Gazette littéraire de l’Europe. Rome: Per Generoso Salomoni, 1765

Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University Library

Piranesi fought in an international controversy about cultural superiority: Roman versus Greek. When the print connoisseur Pierre-Jean Mariette criticized his position, Piranesi responded with a book that combined an essay, a spirited dialogue, and a set of prints. The book is a model of page design. The vignettes Piranesi designed for the texts underpin his argument in favor of the diversity of artistic forms over strict rules. Small prints like this tailpiece feature various types of material evidence, underscoring Piranesi’s assertion that his own experience as an artist made him a better judge of quality than his critic.

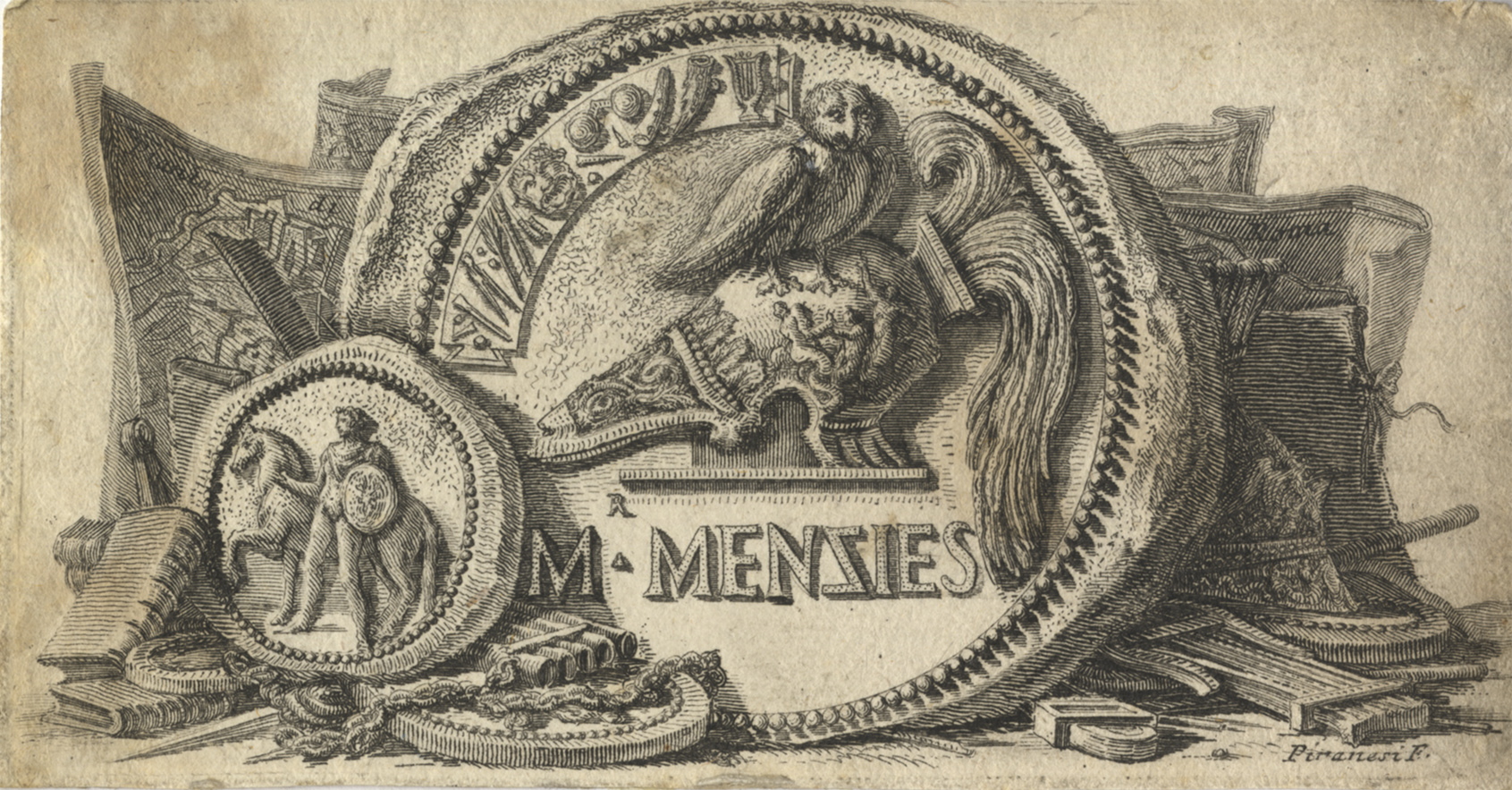

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Vignette for Mr. Menzies, before 1765

Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library, Special Collections, Yale University Library

Piranesi frequently made changes to his copperplates, returning to re-etch their surfaces. However, he did not do this to his vignettes, the smaller prints that he made to insert on sheets of letterpress texts. One remarkable exception is this small print, a rare example of a vignette that Piranesi altered significantly. In this earlier state of the print that he used as the tailpiece in the Osservazioni (1765), the name inscribed under the central medallion reads “Mr. Menzies” instead of “Minervae S.”

Who was Mr. Menzies? A portrait at Harvard by Anton von Maron of Archibald Menzies of Culdares (d. 1777) provides the likely answer. Painted in Rome in 1763, when Menzies was on his Grand Tour, the portrait was made two years before Piranesi published the Osservazione. Menzies, who became Scotland’s commissioner of customs, is probably the person named in the early state of the vignette. He may have commissioned a small print from Piranesi to use as a bookplate or calling card. The copperplate, which survives with Piranesi’s other plates, now has the “Minervae S” inscription, which means that the "Mr. Menzies" inscription must have come first.

Silver coin with bust of Athena (obverse) and owl standing on amphora (reverse), 172–171 BCE

Numismatic Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Piranesi based the design of the Osservazioni vignette on a real coin. He took an Athenian prototype and Romanized several of its elements. In the print, a helmet replaces the amphora under the owl’s talons, and a hieroglyphic tabula ansata replaces an olive branch. Like the objects scattered in the foreground, the elements in the frieze do not seem to derive from any particular source; rather they appear to be an amalgamation of typical objects that appear throughout Piranesi’s work, including the dividers, the mask, and the cornucopia.

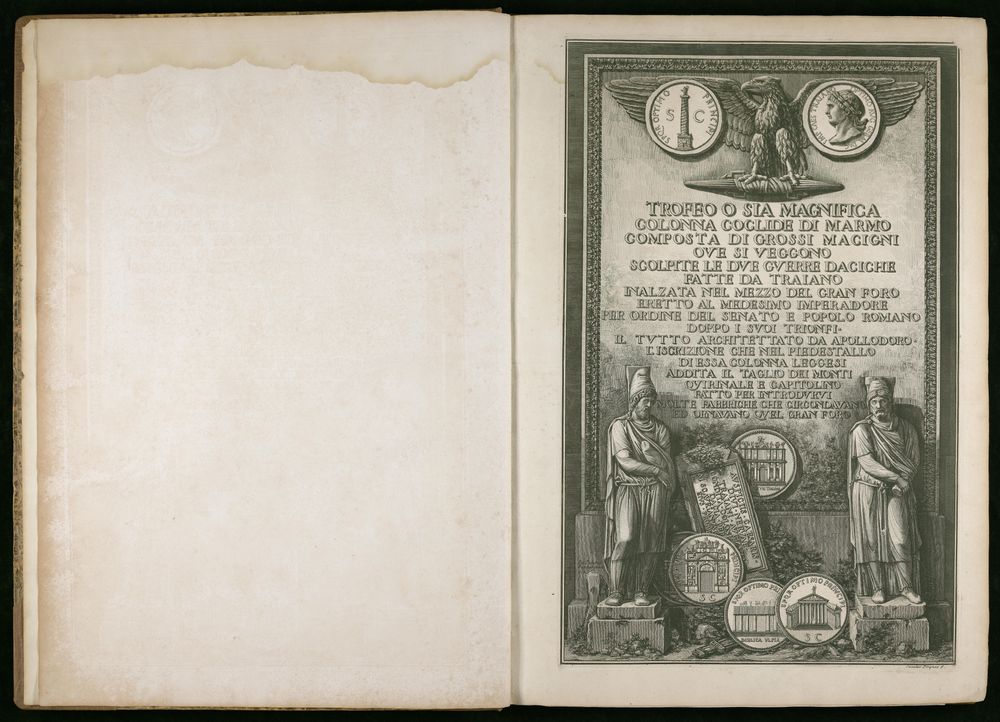

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Trofeo o sia magnifica colonna coclide di marmo. Rome, 1774–1779

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Coins were a pictorial field to Piranesi, a relief surface that combined textual and graphic information in a compact area. In his book about the Column of Trajan, the title page features Trajanic architecture as it appeared on ancient coinage. At the top, the emperor faces his historiated column. Below, two large sculptures of captured Dacians, Trajan’s conquered enemies, stand amid gigantic coins featuring the emperor’s monuments.

Coins

Piranesi studied ancient coins for their depictions of monuments and symbols. This focus on certain pictorial elements differentiates him from most Renaissance numismatists, for example, who tended to focus on images of Roman rulers; their likenesses, perceived as accurate portraits, could be used to identify sculpture. Piranesi’s study of coins was more archaeological, as he used numismatic evidence to help reconstruct lost or ruined structures in his books. The materiality of coins also interested him, because stamped and impressed metal objects had resonance with his own work as an etcher and engraver.

Silver coin with bust of Trajan (obverse) and Trajan's column (reverse), 112–117 CE

Numismatic Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Orichalcum coin with bust of Trajan (obverse) and standing Victory (reverse), 104–111 CE

Numismatic Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Bronze coin with bust of Trajan (obverse) and octostyle temple (reverse), 104–111 CE

Numismatic Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library