Orchestrating Sales

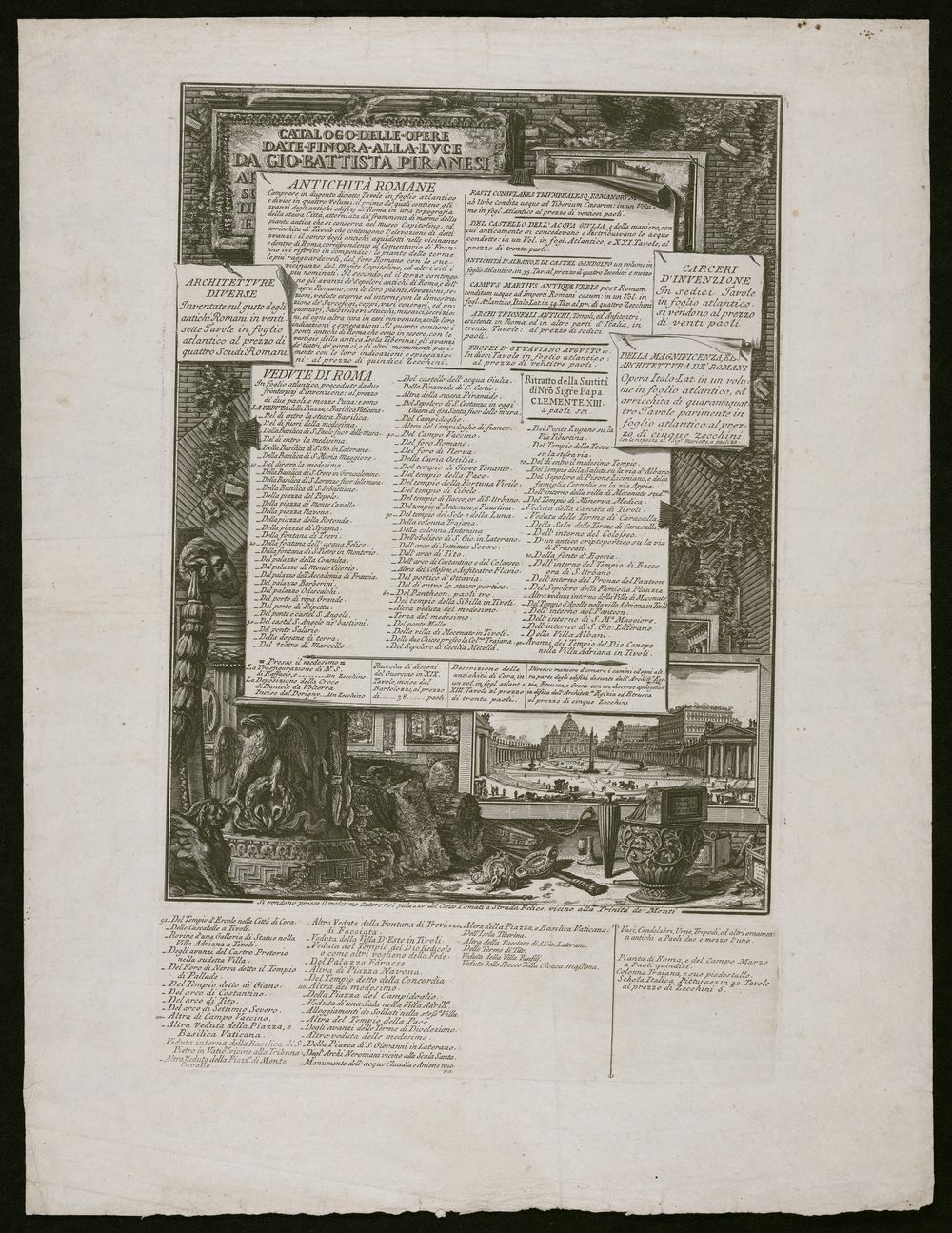

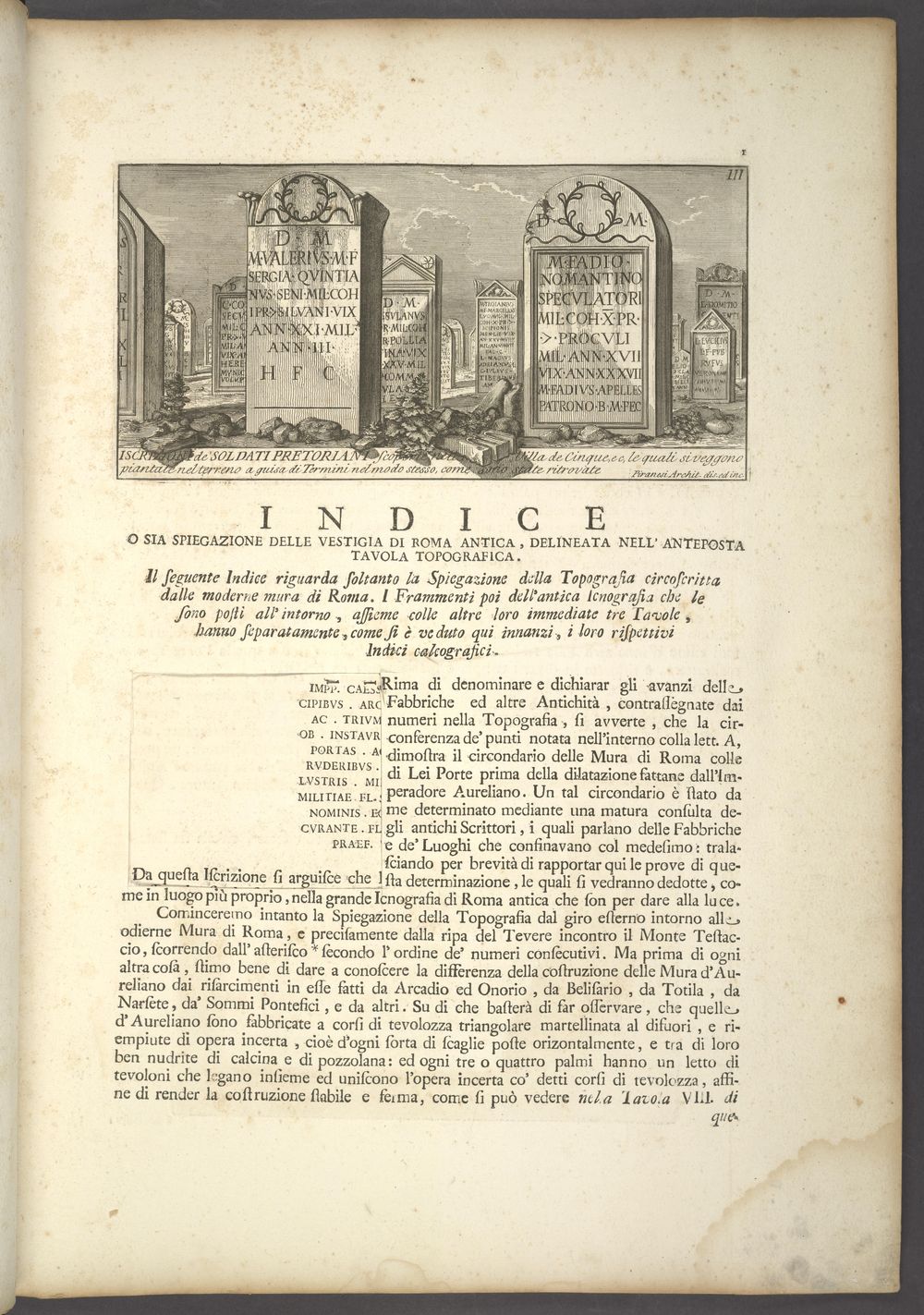

Piranesi orchestrated sales through personal correspondence and a continually updated catalog print. With the Catalogo delle opere, Piranesi turned the list of his works into one of those works. After he moved to his own premises near the Spanish Steps in 1761, Piranesi created this print as an advertisement. It lists Piranesi’s books and prints, together with their prices, against a backdrop featuring some of his wares. He sent copies of it to potential clients to use as an order form and he inserted copies into his books. As Piranesi’s stock grew, so did the etched list of titles, and the plate went through dozens of state changes. Early impressions have a blank space below the list of the Vedute di Roma, which Piranesi used to inscribe customers’ names. In later impressions, the titles cover every available surface and leap out of the bounds of the original plate onto a second plate added to the bottom of the sheet.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Catalogo delle opere date finora alla luce da Gio. Battista Piranesi, 1761

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Andrew Robison, Class of 1962 and Graduate School Class of 1974, in honor of Prof. Robert A. Koch

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Catalogo delle opere date finora alla luce da Gio. Battista Piranesi, 1761 [c. 1776]

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

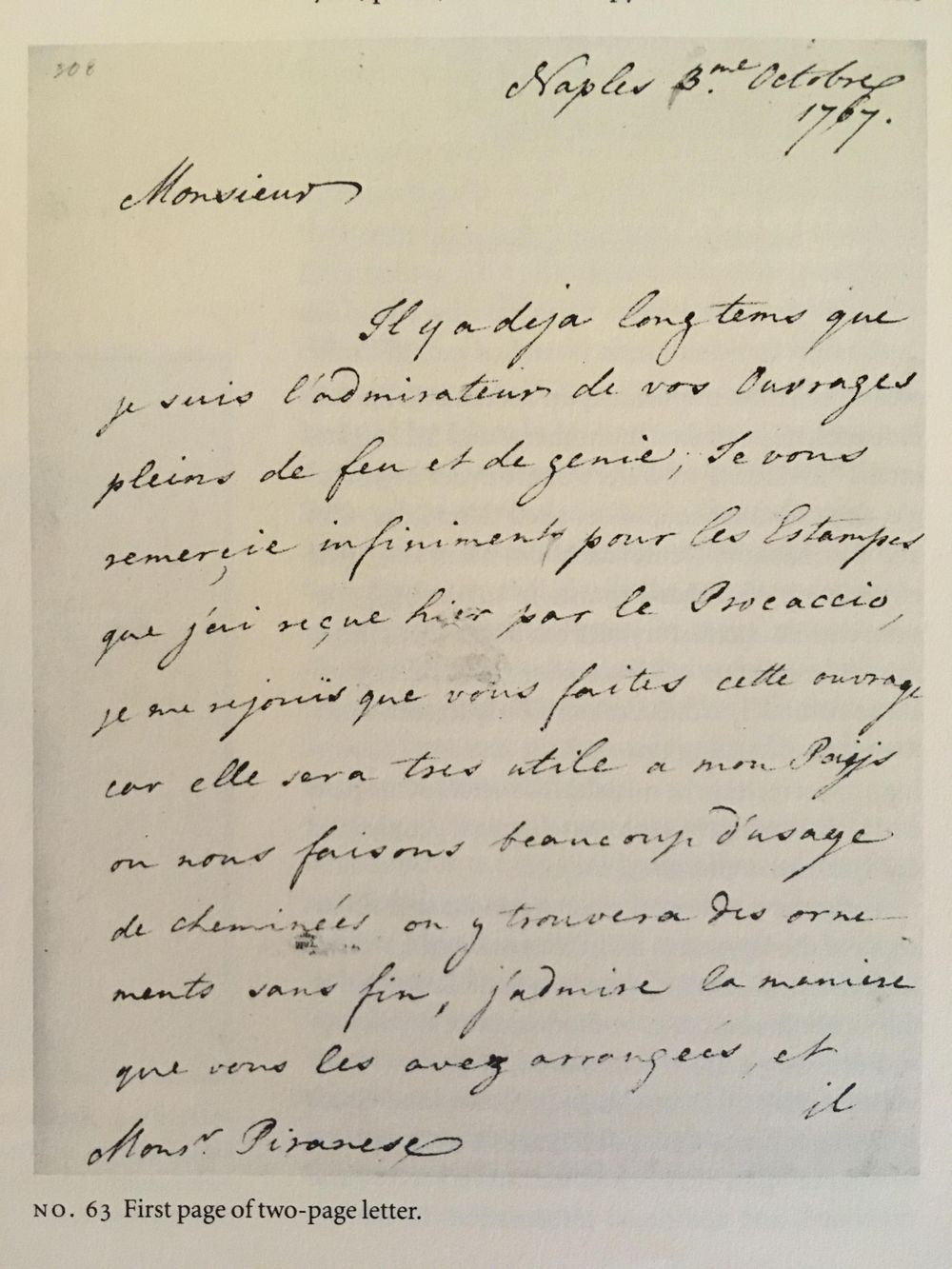

WILLIAM HAMILTON (1730–1803)

Letter to Giovanni Battista Piranesi, October 3, 1767

The Morgan Library and Museum, Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1901

Piranesi knew many of his customers well. In this letter, William Hamilton thanks the artist for prints he had sent and for the notice of his new publication, the Diverse maniere. Famous for his collection of Greek vases and for being the husband of a well-known actress, Hamilton was more than just a customer to Piranesi. As the English ambassador to Naples, Hamilton had extensive contacts with Grand Tourists, which made him useful for advertising Piranesi’s latest publications. Written in French, the language of polite society in the eighteenth century, the letter demonstrates that Piranesi’s business had become a multinational enterprise.

WILLIAM HAMILTON (1730–1803)

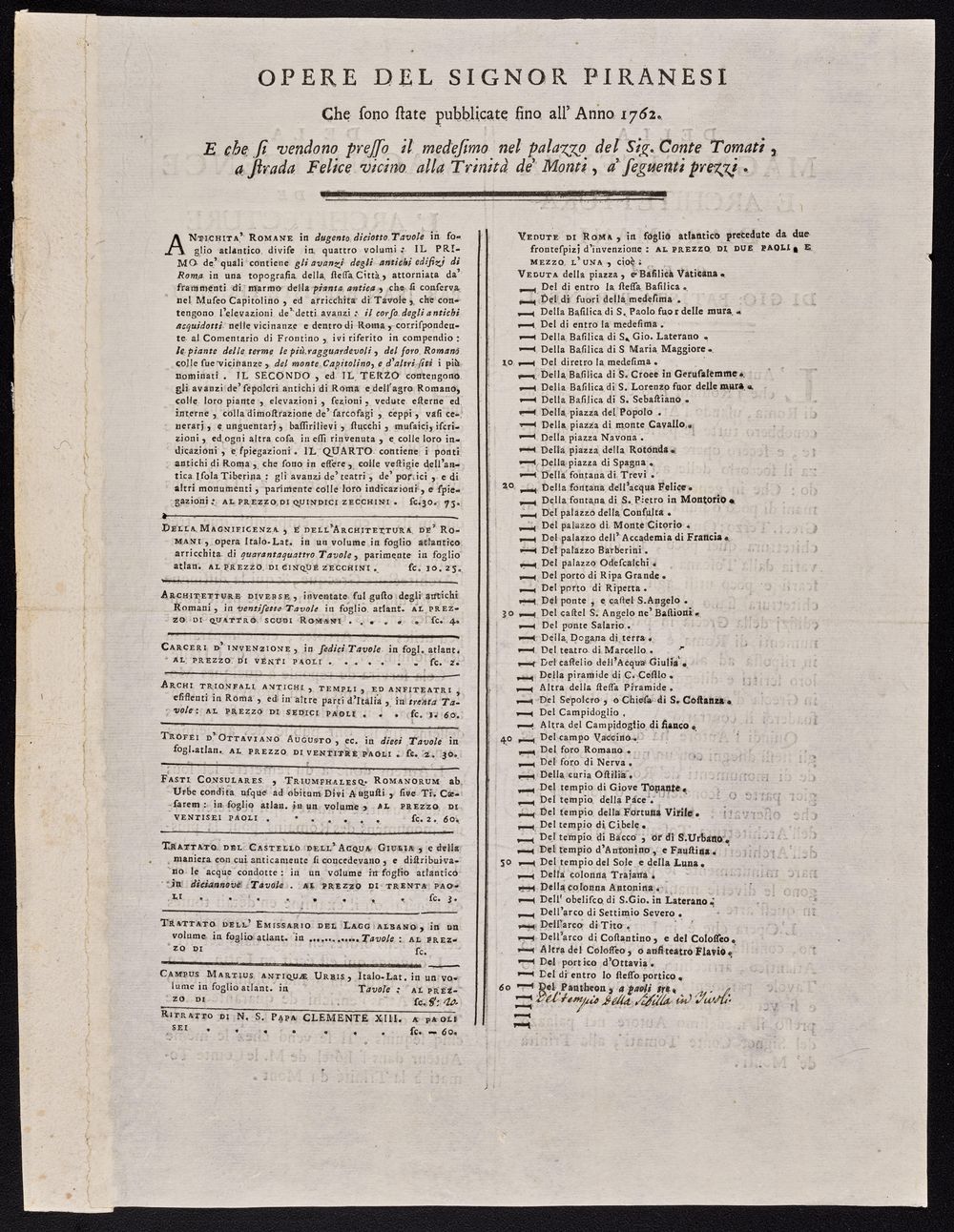

Opere del Signor Piranesi che sono state pubblicate fino all’Anno 1762 [1762]

Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

* New Acquisition

Piranesi opened his own shop in the Strada Felice near the Trinità dei Monti in 1761. At that time, he engraved a catalog print advertising his works for sale. In one of the earliest states of that catalog, on view in this exhibition, the list of his available vedute ends with the view of the Pantheon. At the end of 1762, Piranesi issued this small price sheet, printed in letterpress, listing those same works—except by then he had made another one. At the end of the list, there is a handwritten annotation: Del Tempio della Sibilla in Tivoli, the latest view Piranesi had finished. On the reverse of this sheet is a prospectus for his book Della Magnificenza, printed in French and Italian, that describes his position in an ongoing cultural debate. This sheet is the only recorded version of this price list, issued early in the artist’s career.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Opere del Cavalier Piranesi, che si vendono sciolte presso il medesimo nel palazzo del Sig. Conte Tomati … Oeuvres du Chevalier Piranesi, qui se vendent chez lui méme dans l’hotel de M. le Comte Tomati, [c. 1778]

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Piranesi’s market grew well beyond Rome. Made around the time of his death, this broadsheet lists the titles and descriptions of his works, along with their prices, in French on one side and Italian on the other. In the central column, an entry describes a book of views of Paestum, just before the list of vedute. The entry does not give the book’s price or its total number of plates; corrections to the entry have been added by hand. Piranesi’s sons finished and published this book after their father’s death, and the broadsheet is suggestive of its limbo state at the end of his life.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

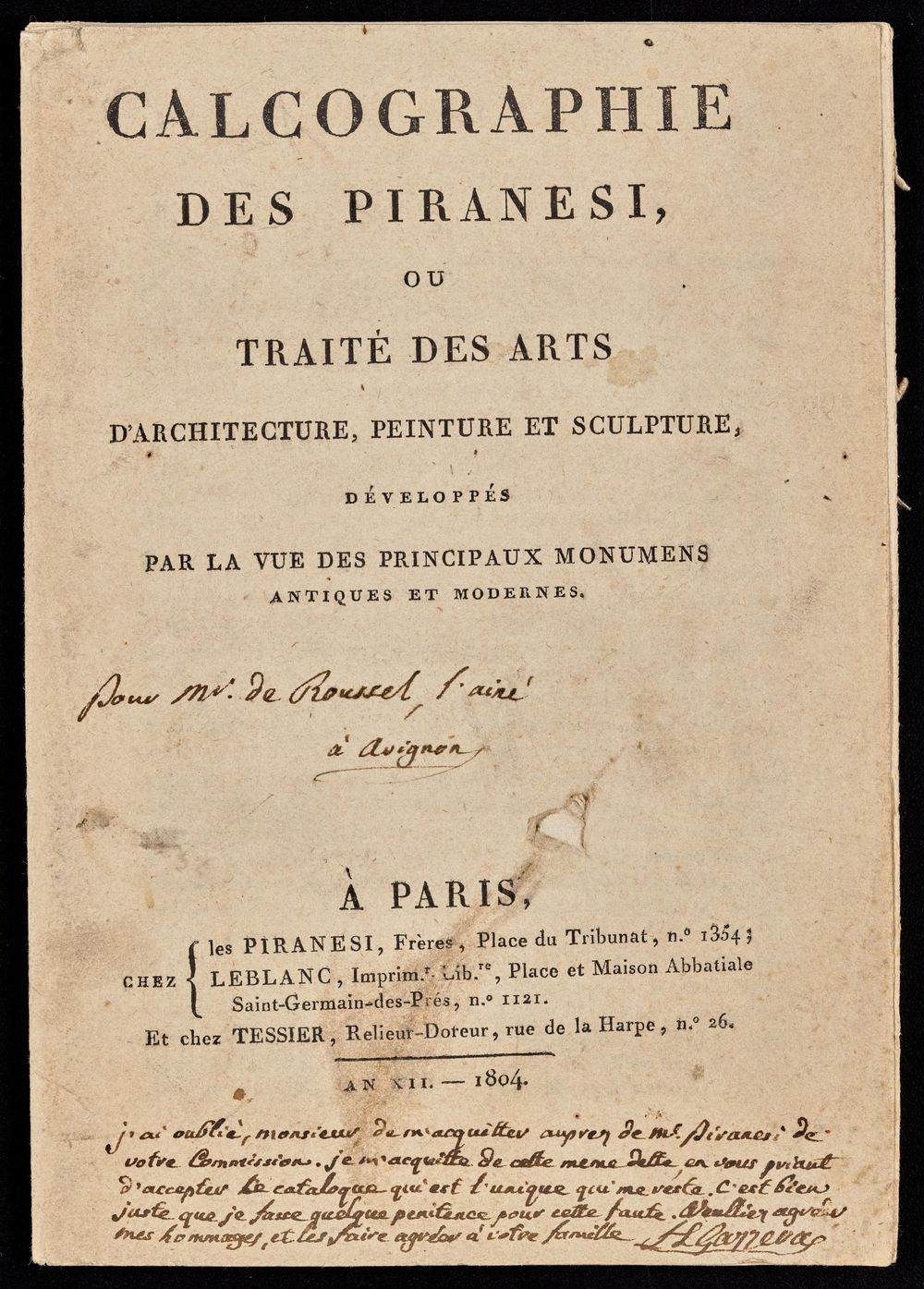

Calcographie des Piranesi; ou, Traité des arts d’architecture, peinture et sculpture, développés par la vue des principaux monumens antiques et modernes, 1804

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Piranesi’s sons began issuing their own printed catalogs after their father’s death, and continued to do so after they moved the business to Paris. Once they ran out of the letterpress texts that had been an integral part of Piranesi’s books, the sons focused on selling impressions of his copperplates. They advertised enormous multi-volume collections of his prints as the “complete works”, and eventually saturated the market. Their business ultimately failed. In the long term, the sons’ business strategies played a large role in the modern conception of Piranesi solely as a printmaker rather than as a maker of books.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Calcographie des frères Piranesi [c. 1804]

Rare Books, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

The handwritten annotations on this pricelist remind the reader why Piranesi etched his Catalogo print. Whenever he published a new book or raised the price of an item, he could re-etch the Catalogo print to reflect those changes. When Piranesi’s sons needed to update a pricelist set in letterpress, they had to print a completely new list. Designed to accompany their catalog, this pricelist has a handwritten addition noting the Paris address where customers could buy the works. The listed items include those by Piranesi himself as well as newer works published by his sons.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Le Antichità Romane, vol. 1. Rome: A. Rotilj, 1756

Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University Library

This battered volume of the Antichità Romane demonstrates vividly the effects that the market for Piranesi’s prints has had on his books. This cannibalized copy, in which individual images have been excised from their pages, shows how owners of Piranesi’s books pursued his prints without regard to their original formats or intellectual contexts. Prints can be hung as art on walls, and so for centuries they have been more commercially valuable than books, although this is no longer the case. This particular volume has a fascinating history. It once belonged to James Caulfeild, the wayward patron of the Antichità Romane who Piranesi infamously memorialized in his Lettere di giustificazione. Caulfeild’s coat-of-arms appear on the book’s binding.

Head of a serpent carved in limestone, Egyptian

Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Edward Sampson, Class of 1914, for the Alden Sampson Collection

Perhaps Piranesi would have enjoyed the fact that Charlemont’s copy of the Antichità Romane (above)--the very book the patron had declined to support--met such a sorry fate. Whoever mutilated that volume, robbing it of its images, left its words behind: the carcass is a telling monument to the dual nature of Piranesi’s books and to his belief in the permanence of writing. Piranesi used the ouroboros, the snake that bites its own tail, as part of his personal dedication print, intertwined with the tools of his trade. The destroyed Antichità Romane is itself a speaking ruin, a story that has come full circle.