Recycling Sheets

Single sheets of paper link together the many stages of Piranesi’s book production, and connect aspects of his complex world of art and commerce. Many of his sheets have traces of multiple uses: the pen and ink lines, washes, and rubbed chalk of his drawings share space with impressions from his and his associates’ printing presses. The first thoughts that he put down on paper appear alongside their eventual development in his book pages.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

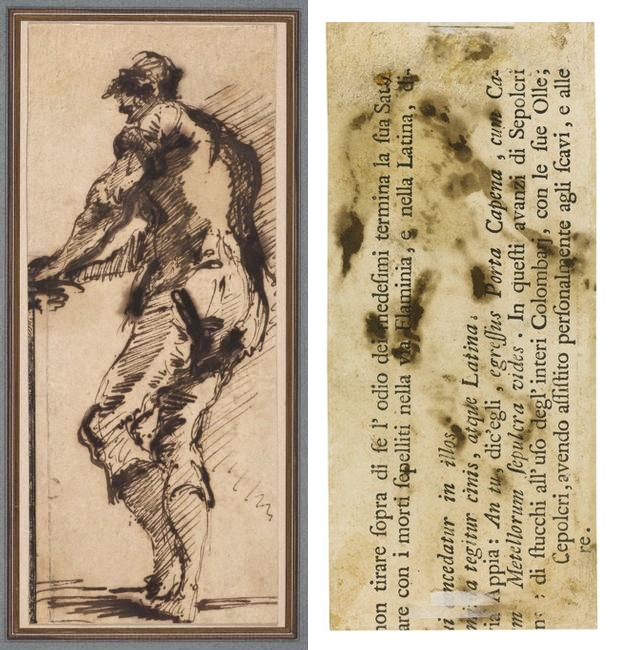

Standing Man Seen from Behind, after 1753. Pen and brown ink, brown wash, intaglio, letterpress

Private Collection

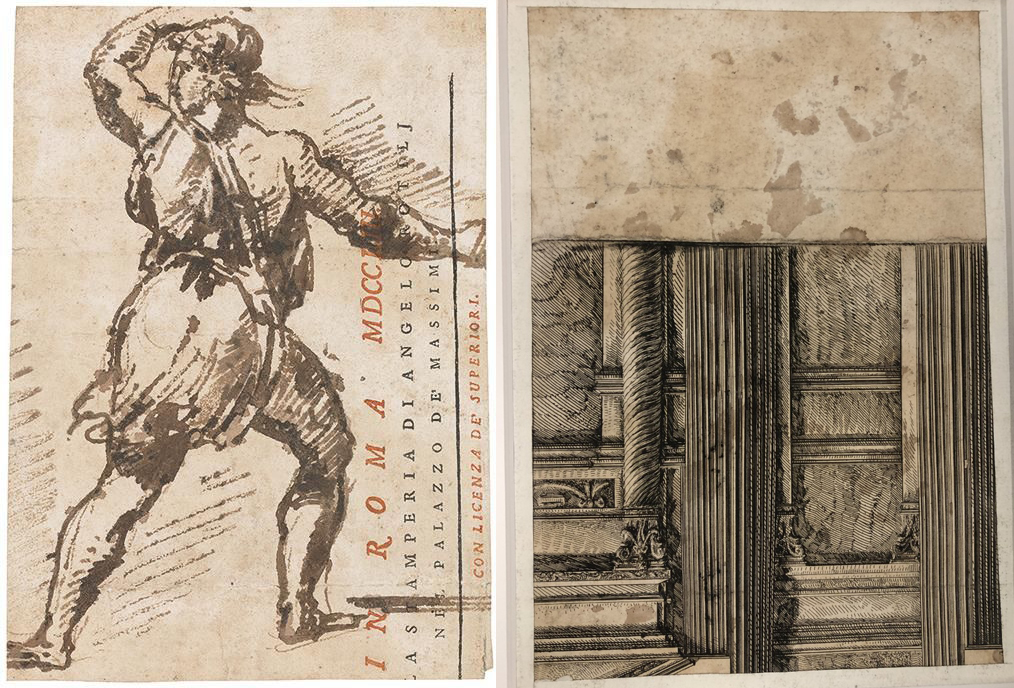

This piece of paper combines letterpress, copperplate printing, and drawing all on the same page, though each layer was created at a separate moment in time. The letterpress layer came first. Piranesi’s associate Angelo Rotili used this sheet of paper to proof a colophon for a book that never made it to publication. The legible fragment on this sheet tells us that this book was to be printed in Rome in 1753 at Rotili’s press in Palazzo de’ Massimi; it had a licenza de’ superiori, or official printing license. The license to print a book was granted only after a censor had examined a complete copy; receiving one was one of the last steps to publish a book in eighteenth-century Rome. Thus this sheet was originally a title page for a book, one that was ready to be offered for sale.

Next, Piranesi used the piece of scrap paper from Rotili to test one of the plates for his Parere su l’architettura sometime after 1767. Part of the metal plate was inked, the dampened scrap of Rotili paper was placed on top, and then it was run through a press to create the impression. Finally, Piranesi made the drawing. Paper has to be damp to be run through a press, so the drawing must have been his last return to the page. Piranesi copied the figure from another print, Marco Dente’s Entellus and Dares Fighting in Front of Classical Ruins.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Man with a Raised Arm, after 1750. pen and brown ink, letterpress

Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, Gift of John D. Reilly ’63

Piranesi records a printer, sleeves rolled up and wearing a thick apron. The verso is a fragment of letterpress. Although most of the text has been trimmed away, it can be reconstructed. The snippet describes the tomb of the freedmen of Augustus, discovered in 1724 on the Appian Way. These lines appear in a book by Antonio Francesco Gori published in 1727. Yet this sheet cannot be a page from Gori’s book because the layout of its text does not match. Instead, this seems to be a condensed excerpt. Extracts of other texts commonly appear in early modern books about antiquities: quoting earlier texts was a means to build on previous scholarship.

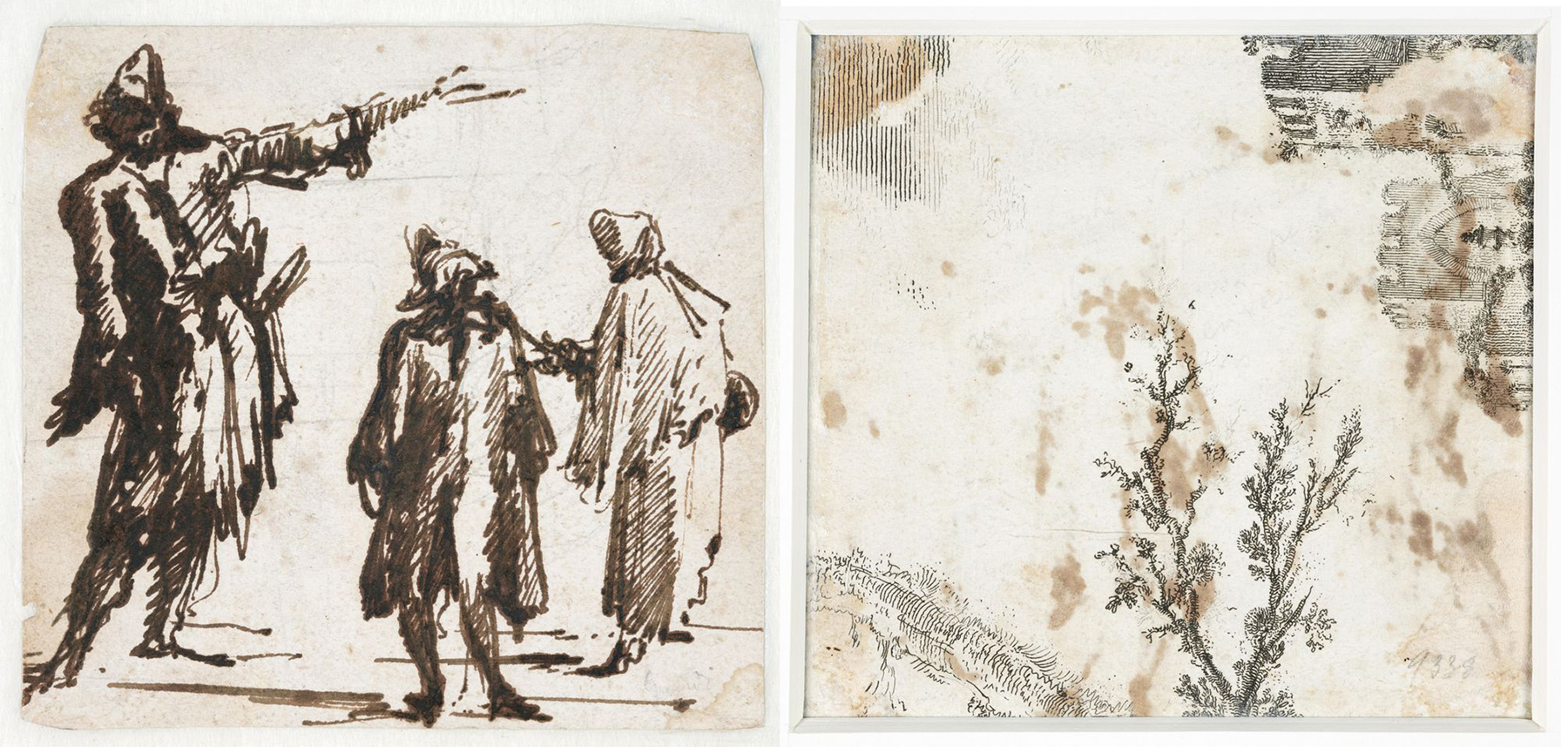

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

A Standing Man at Work, c. 1760-1769. Pen and brown ink on heavy cream laid paper, letterpress

Princeton University Art Museum, Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund and Ethan O. Meers, Class of 2003, and Anne S. Bent Acquisition Fund

With his sleeve pushed up and his legs crossed, the man in this sketch is hard at work. At first glance, the drawing seems to be made entirely in pen with black ink. Yet the vertical line of the table is not drawn but rather printed. The ridge left where the copperplate pressed into the paper still can be felt. Letterpress covers the sheet’s verso: nine lines of Italian and Latin text discuss ancient tombs in Rome. The text begins with the “dead buried along the via Flaminia and the via Latina” and moves on to those on the Appian Way, quoting Juvenal and Cicero. The final lines cite the author’s personal participation in excavations.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Three Figures, One Gesturing to the Right, c. 1755. Pen and brown ink over black chalk, intaglio

Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

* New Acquisition

Piranesi loved to draw the people around him, whether they were assistants in his workshop or Romans on the street. He sketched these three figures on the reverse of one of his own proofs, an impression of the Veduta del Sepolcro di Cajo Cesto. This etching, which shows the Pyramid of Cestius and the Porta San Paolo, was published in the Vedute di Roma.

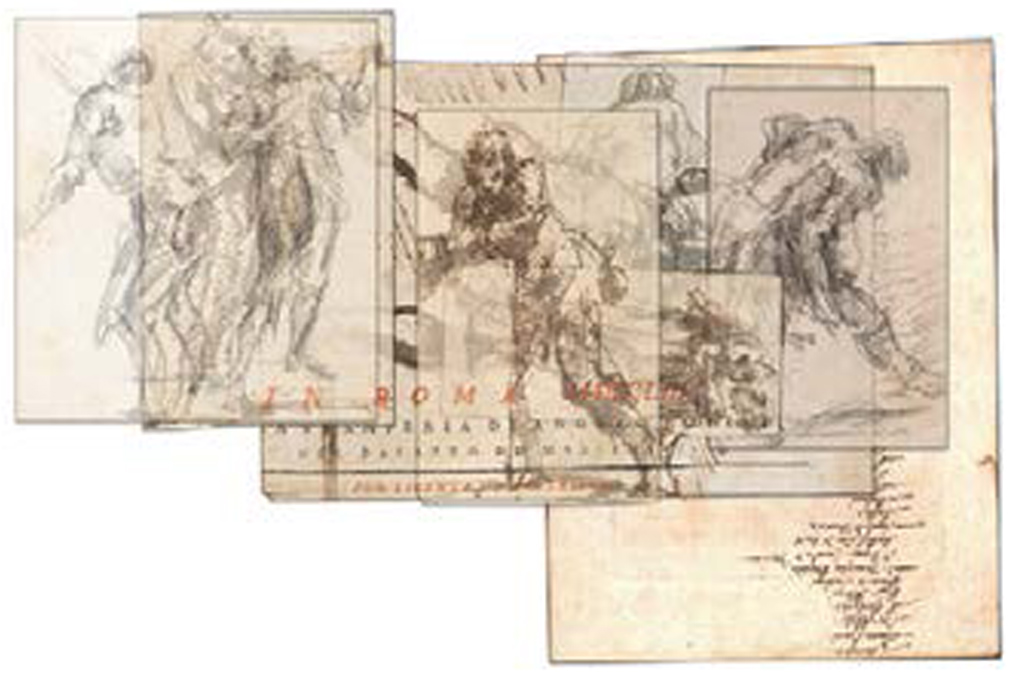

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI (1720–1778)

Rotili collage

Piranesi inventively recycled paper fragments.

This collage combines eight separate scraps of paper, all fragments of many copies of the same printed title page. When assembled together, these scraps reveal the name and address of a printer, Angelo Rotili, and the year 1753. The title page comes from a lost book by Piranesi, a work on tombs that he began but never published. He used its discarded title pages as drawing paper to study the human figure, and on one of the sheets, he made a list of recipients for another of his books.