DYN

By Antonio Warren '25

DYN, Mexico, and Surrealism's New Frontier

“And not just beings and things and material noises. But still myself chasing myself or going on beyond”

Surrealism in Mexico

Surrealism sits at the frontier: at the cutting edge of artistic expression, at the boundary between the physical and the psyche, at the borders of countries primed to welcome fleeing artists. Amidst the rise of fascism and the subsequent threat of persecution during the 1930s, surrealists sought safe havens outside of Europe. Mexico, exercising an “open-door policy” and home to acclaimed artists like Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, served as the destination of many creatives fleeing violent totalitarianism (Tate Modern 2022). surrealists, specifically, had begun to travel to Mexico by 1936, when Antonin Artaud visited the country. Artaud, discontent with Europe’s deteriorating culture, viewed Mexico as an oasis rich with mystic culture and natural beauty. Artaud’s visit sparked an influx of surrealist artists into Mexico. By 1938, André Breton had conducted a four-month-long excursion through the country, and by the early 1940s, the likes of Benjamin Péret, Luis Buñuel, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, and many more had followed suit with the intention of staying indefinitely (Andrade 2003, 68). The European surrealists who trailed Artaud viewed Mexico as the next global metropolis of surrealism. Surrealists imagined injecting their movement with new life by tapping into Mexico’s cultural wealth and natural beauty. Breton, in a 1938 essay on Frida Kahlo, singled out Mexico as the place par excellence for imagination to grow (Strom 2023, 261). Wolfgang Paalen, an Austrian-born surrealist painter and editor who migrated to Mexico in 1939, shared this view. Intent on spreading his own version of surrealism, Paalen founded the periodical DYN in Mexico City in 1942, confirming Mexico as the new hotbed of global surrealism.

For more information on the spread of surrealism in Mexico City, please visit Katherine Belilty's "Surrealism in Mexico City."

A New Surrealism

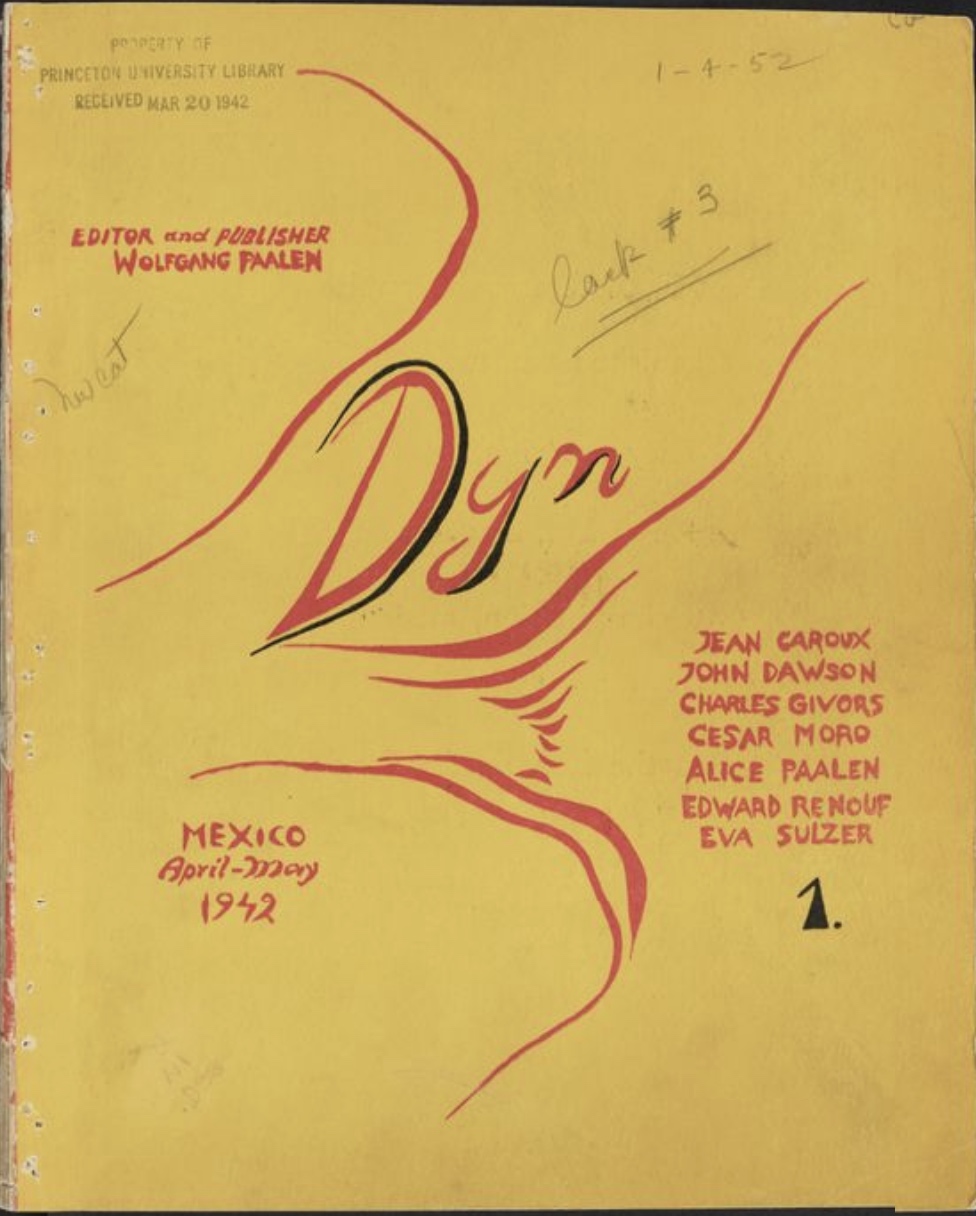

In 1942, Wolfgang Paalen founded the surrealist art journal DYN in Mexico City and published six issues until 1944. Paalen immigrated to Mexico in 1939 in the wake of Nazism and Breton’s own visits to the country the year prior (Driben 2003, 67). Though DYN relied on the movement, artists, and global community that Breton helped inspire, Paalen’s publication sought to differentiate itself from Breton’s idea of surrealism. DYN “...[served] as an alternative to - in fact, a slap in the face of - Breton’s socio-idealistic brand of Surrealism” (Heller 2003, 162). Having taken issue with Breton’s focus on politics, Paalen sought a contemporary surrealism rooted in a common scientific method rather than volatile political motives. Over DYN’s six issues, Paalen attempted to free surrealism of the influences, like politics, that he deemed detrimental to the movement’s persistence and growth.

“DYN 1” best illustrates the editorial beliefs and grievances with the state of surrealism that led Paalen to found the journal. The interior cover of the inaugural issue contains a statement that stresses the freeing potential of modern art amidst “totalitarian tyrannies,” like the one from which Paalen escaped. Two pages later, Paalen highlights the three priorities for DYN: DYN’s independence of political and commercial interests, but also its independence of specific “-isms,” fixed schools of thought or art; the magazine’s commitment to be a forum for emerging thinkers and artists; and DYN’s consistency of publication and format. This first statement in DYN bears special relevance to Paalen’s disagreements with Breton, as he refuses any kind of subjugation to fixed ideologies and rigid “schools.” Following DYN’s list of foundational principles and the first issue’s table of contents, “DYN 1” features three essays written by Paalen that further highlight his reasons for founding a new surrealist periodical.

In the first essay titled “The New Image”, Paalen contends that DYN, and artists at large, must distance themselves from “beauty” and “ugliness”, meaning the aesthetic realm. He states: “The possibility of conceiving of works of art in terms of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ implies the perfect interrelation with the fundamental problems of the community which produces them. For the authentic work of art is no ‘superstructure’ and never has been” (7). Paalen then goes on to characterize art as a fundamental method of being in the world, akin to science and religion, not just a “superstructure.” For Paalen, art served as an integral part of the life of a community and not just an issue of aesthetics.

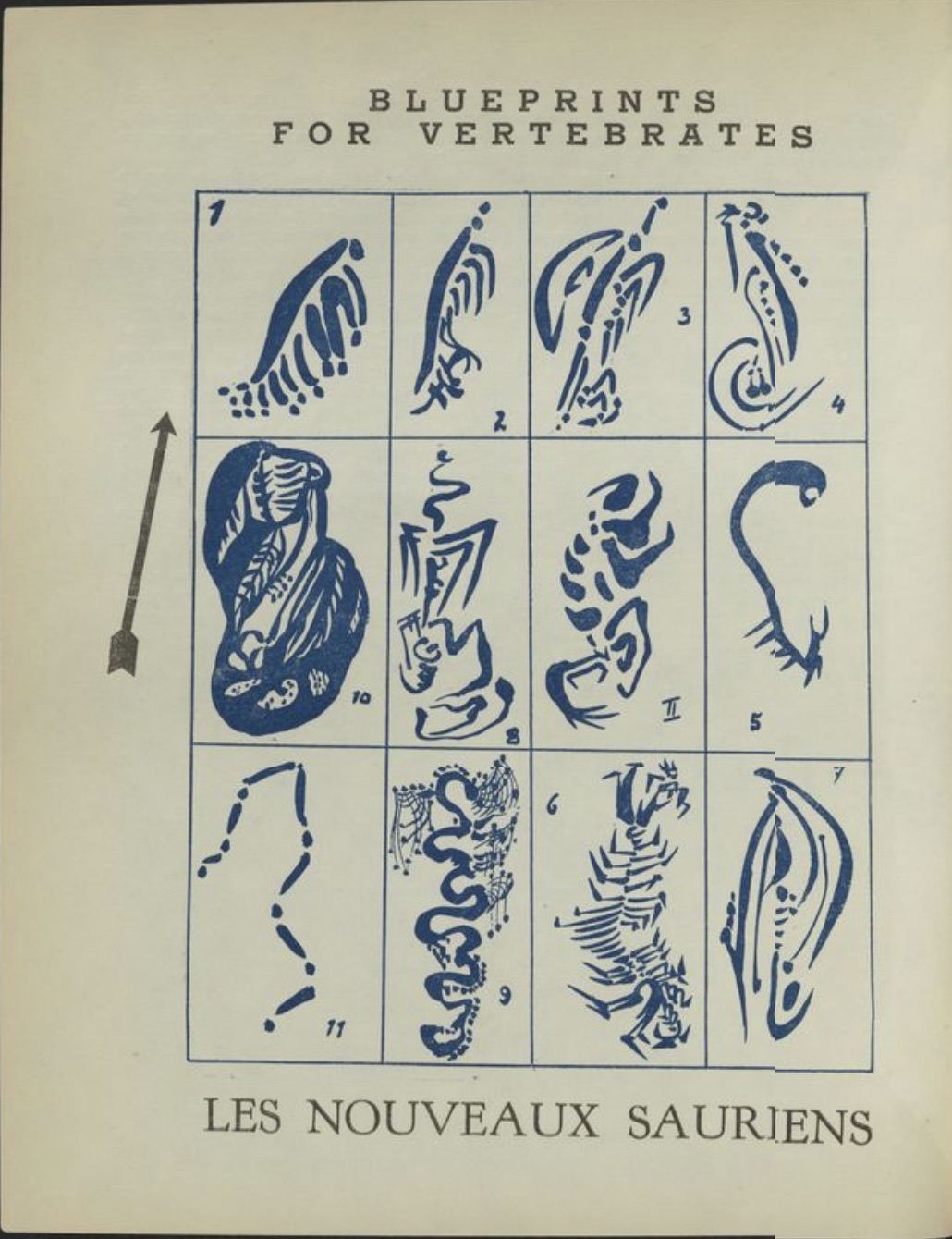

The essay “Regionalism in Painting” by American artist Edward Renouf, the assistant editor of DYN, further develops Paalen’s connection between art and community. Renouf posits that since an individual can only paint the culture with which they develop, only individuals with “‘universal spirit’” can truly achieve excellence in painting (22), calling artists to expand their horizons, hinting at a possible “...comprehension of all peoples…” (22). This universalist understanding of art is doubled by the illustration preceding Renouf’s essay, “Blueprints for Vertebrates”, by Charles Givors. This is a Darwin-like classification, a blue chart of numbered, fossil-looking forms. The scientific nature of Givors’s illustration seems to be backing the universalist spirit of the article.

Moreover, DYN's “scientific” approach to surrealism is visible in its format. From “sparsely illustrated covers” to “highly functional interior layouts”, issues of DYN maintained a conservative, highly visual appearance (Heller 2003, 163). Similarly, later issues featured works like American artist Alexander Calder’s sculpture Small Feathers (1931) that carried motifs derived from mathematical logic and planetary movements (Leddy 2012, 27). Despite Paalen’s opposition to surrealism as it had developed under Breton’s leadership, DYN still shares some fundamental ideas with it. For example, Renouf’s call to seek out other cultures and communities in a universalist spirit is in concordance with the universalism central to surrealism from its birth in 1924. Indeed, DYN’s target audience corroborates the idea that the publication remained closely related to other surrealist periodicals, despite Paalen’s critiques of Breton and the state of surrealism by the mid-1930s. The first issue of DYN features articles exclusively in English and French, and throughout DYN’s two-year lifespan, Paalen targeted the same crowd of New York City artists as did Breton and other surrealist periodical editors during the same period. DYN represented Wolfgang Paalen’s desire to create a magazine “ as the center of a new artistic manifestation” (Heller 2003, 161-62).

A Global Stage

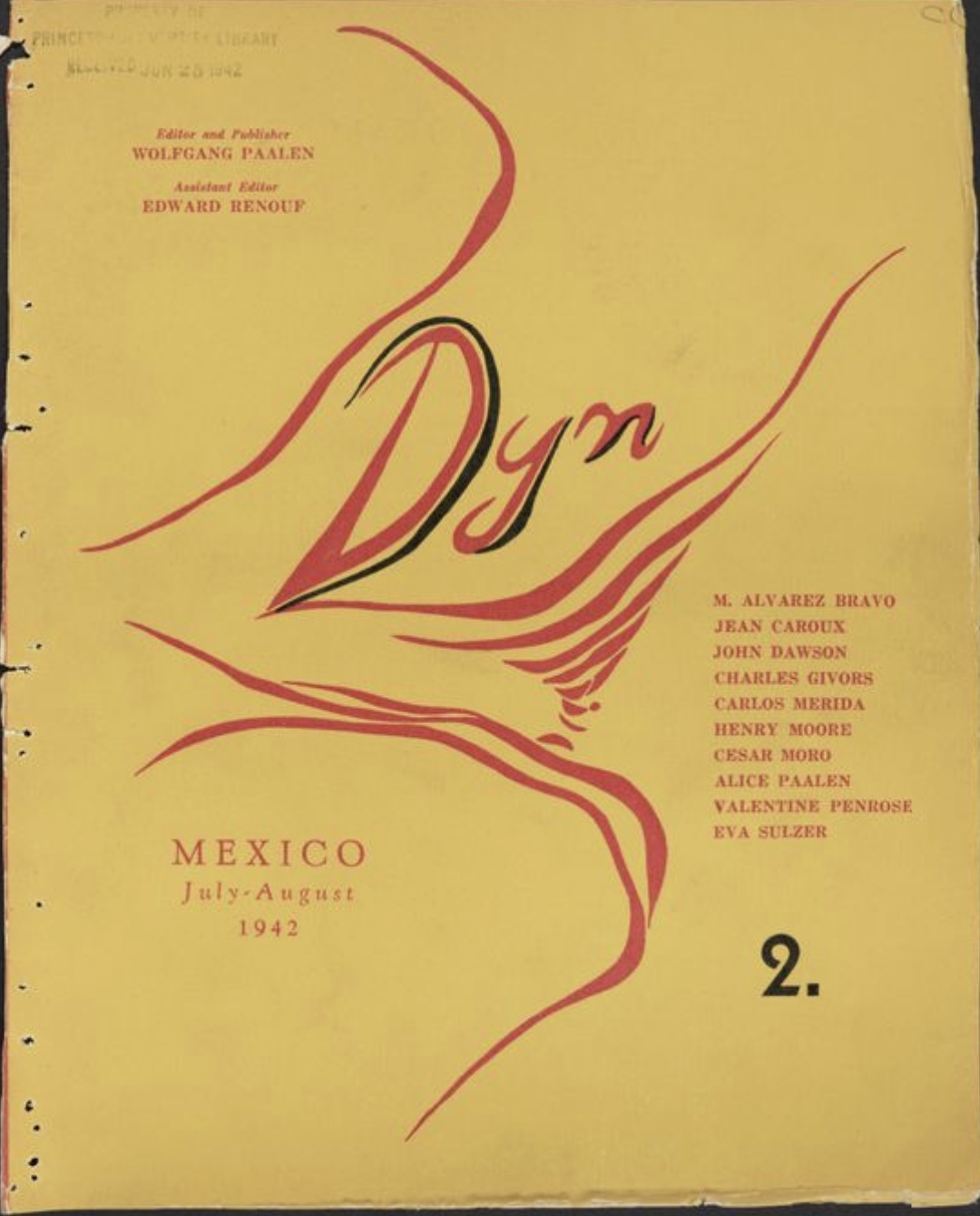

Following DYN’s revolutionary first issue, “DYN 2” perfectly captured Paalen’s pursuit of international recognition and his qualms with the politics of Breton. This second issue, published two months after the first, features the same fiery yellow and red cover design as “DYN 1.” Nonetheless, the scope of “DYN 2” far exceeds that of the first issue, as it featured a bold questionnaire titled “Inquiry on Dialectic Materialism” that Paalen sent to Lionel Abel, George Barker, André Breton, Nicolas Calas, John L. Childs, Albert Einstein, James T. Farrell, and Charles Givors, among others (49). Paalen’s inquiry included three questions:

1. “Is Dialectical Materialism the science of a verifiable ‘dialectic’ process: ‘...the science of the universal laws of motion and evolution in nature, human society and thought?’

2. Is the ‘dialectic method’ a scientific method of investigation? Does science owe important discoveries to this method?

3. Do you consider the following statement valid: ‘ Hegel in his logic established a series of Laws: change of quantity into quality, development through contradictions, conflict of content and form, interruption of continuity, change of possibility into inevitability, etc., which are just as important for theoretical thought as is the simple syllogism for more elementary tasks?’”

On the surface, “Inquiry on Dialectic Materialism” seems simply concerned with clarifying the validity of Dialectic Materialism and the dialectic method. However, Paalen’s survey is aimed as an attack on the Marxism at the core of Breton’s surrealism. The American art historian Meyer Schapiro noted that Breton’s words do not represent a genuine philosophical question and “‘...were not inspired by a primary concern with the theoretical and practical problems of socialism’” (Leddy 2012, 3). Rather, considering the status of the intellectuals that Paalen attempted to survey, his inquiry gives the impression that he sought validation among the same New York City audience that Breton was trying to influence. In “Inquiry on Dialectic Materialism”, Paalen even includes a non-answer from Albert Einstein who decided not to share an opinion and stated, in his letter, that “‘[The content of Engels’s Dialectic and Nature] is not of any special interest either from the standpoint of contemporary physics or of the history of physics’” (50). With these responses, Paalen presented his periodical as a global stage for intellectual debate.

Understanding or Exoticization?

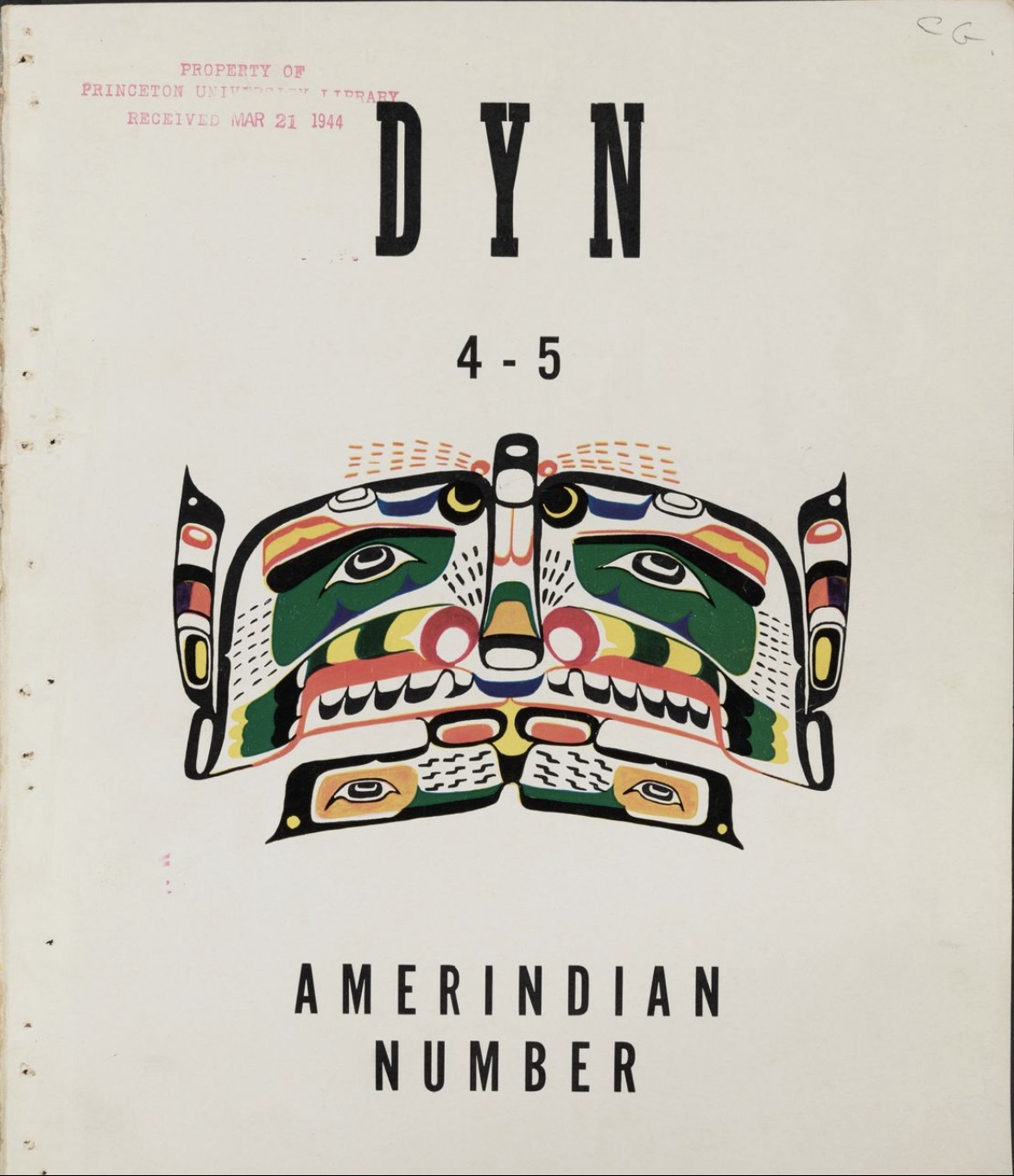

DYN’s double issue "DYN 4-5”, titled the “AMERINDIAN NUMBER” returns to the connection between art and community. The second page of this issue states its purpose: to “...present to the public a practically unknown art, that of the ancient Northwest Coast…” (2). “Amerindian” and “ancient Northwest Coast” refer to the indigenous populations of Mexico and other parts of Central America, such as the “culture of Tlatilco, Valley of Mexico”, and the Mayan people, among others (2).

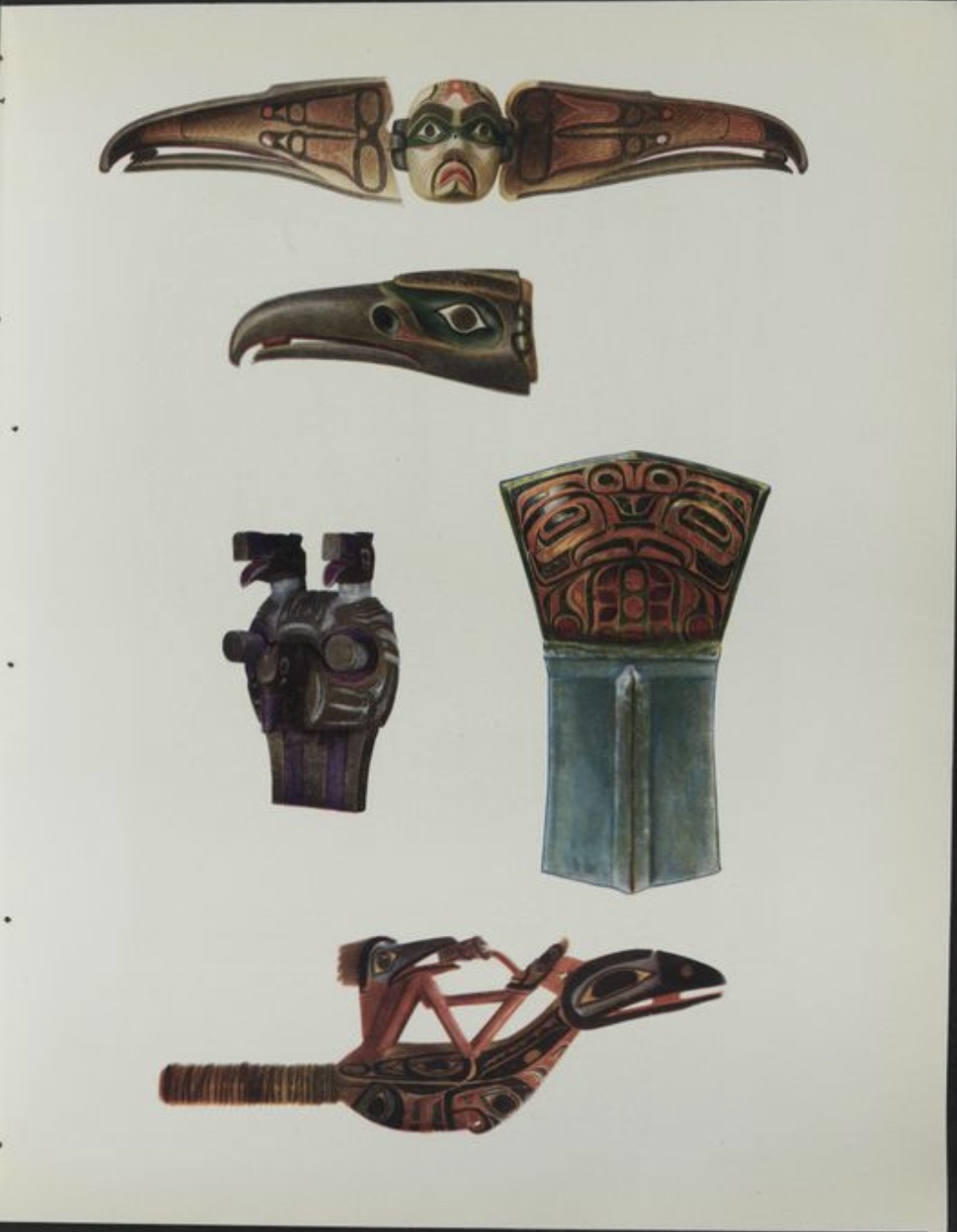

The format and contents of the “AMERINDIAN NUMBER” reflect the double issue’s scope and anthropological focus. Furthermore, the production quality of “Issue No. 4-5” marks a shift in DYN’s form. Published in 1944 on 84 pages of laminated paper, the issue features larger, higher quality pages, no glued elements, and special “plates” dedicated to images and illustrations. Unlike the first three DYN issues, “4-5” features a cover indicative of its contents - an indigenous, colorful mask of an “Amerindian” people. The plethora of images included in “Issue No. 4-5” all relate to “Amerindian” populations, from photographs of artifacts to portraits of indigenous Mexicans, to maps and sketches of archaeological sites. For instance, one of the plates in "4-5" displays several items that Paalen, himself, collected from Vancouver Island, B.C. As stated in the issue’s introduction, many of the included indigenous elements were presented for the first time to a global audience unfamiliar with these cultures. Moreover, Paalen featured works by contemporary Mexican artists, like “Tlatilco - Archaic Mexican Art and Culture” - an exploration of ancient, nomadic Mexican populations and the artifacts they left behind by painter Miguel Covarrubias.

Nevertheless, Paalen’s presentation of native cultures and histories “...exemplifies the complex relationship between learning and exhibiting Indigenous artworks and the reconceptualization of the surrealist experience influenced by local mythologies of the Americas” (Strom 2023, 329). Though Paalen centered “DYN 4-5” on indigenous art and even involved Mexican artists, he maintained curatorial control of the issue as a member of the Western art world deeming indigenous, “Other” cultures as “primitive” (336). DYN’s position alone as an art magazine attempting to present an anthropological study of indigenous cultures further complicates the legacies of “AMERINDIAN NUMBER” and DYN. The ambiguity of DYN’s position and Paalen’s ambitions with the “AMERINDIAN NUMBER” become even more salient in the issue’s presentation of living indigenous people. For instance, one page taken from Paalen's essay "Totem Art" features a certain “Chief Tlinghit” above a blanket, and to the left of a wooden box; the indigenous individual is made to appear almost as an artifact (22).

DYN's Legacy

DYN’s six issues published between 1942 and 1944 were an important moment for the development of global surrealism. DYN’s marked interest in science and indigenous cultures pointed to new directions for the development of surrealism. Outside of the movement, Paalen’s periodical influenced several emerging artists of the time, especially a new generation of American painters including Lee Mullican, Harry Jackson, and Robert Motherwell (who translated Paalen’s essay “The New Image” from French to English). Even Jackson Pollock kept the entire collection of DYN in his personal library (Sawin 1995, 267). Author and art critic Martica Sawin captures the scale of DYN’s influence on American art in her work Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School, pointing out DYN’s important role in laying the conceptual groundwork for abstract expressionism. Sawin includes a Wolfgang Paalen quote from his essay titled “Art and Science” from DYN’s third issue before acknowledging its impact on abstract expressionists:

“‘The new directions of physics as much as those of art led me to a potential concept of reality opposed to any concept of deterministic finality. This concept, which I shall call dynastic (from the Greek word dynaton: the possible) or the Philosophy of the Possible, excludes any kind of mysticism and metaphysics, because it includes the equal necessity of art and science. . .The new theme will be a plastic cosmogony, which means no longer a symbolization or interpretation but, through the specific means of art, a direct visualization of forces which move our bodies and minds.’ In these words, written [by Paalen] in 1942, we read both the title of the first journal of the abstract expressionists, Possibilities, whose sole issue appeared in 1947, and a precise description of what Jackson Pollock began to do with paint in 1946 as he gave visual form to ‘the forces that move our bodies and minds’” (Sawin 1995, 267).

Bibliography

Andrade, Lourdes. "'Do you remember, Rousseau...?'" In Artes de Mexico, no. 63, Mexico in Surrealism: Transitory Visitors (2003): 65–80. Accessed May 7, 2024. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24315376.

Cole, Lori. "Reimaging Surrealism through Journals." In Surrealism Beyond Borders, by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2021. Canvas.

Desnos, Robert. "Sleep Spaces." In Essential Poems and Writings of Robert Desnos, edited by Mary A. Caws. Boston: Black Widow Press, 2007. Canvas.

Driben, Lelia. "Paalen: The Great Transpatriate." In Artes de Mexico, no. 64, Mexico in Surrealism: Creative Transfusion (2003): 65–80. Accessed May 7, 2024. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24315946.

Heller, Steven. Merz to Emigre and Beyond: Avant-Garde Magazine Design of the Twentieth Century. London: Phaidon Press, 2003. Canvas.

Landau, Ellen G. 2016. “Review of Wolfgang Paalen, Form and Sense.” Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 9 (1): 67-72. https://keep.lib.asu.edu/libraries/pdf.js/web/viewer.html?file=https%3A%2F%2Fkeep.lib.asu.edu%2Fsystem%2Ffiles%2Fc159%2FLandau.pdf.

Leddy, Annette., and Donna Conwell. Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle In Mexico. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2012.

National Gallery of Art. “Tower 2: Alexander Calder.” Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.nga.gov/features/tower-2-alexander-calder.html.

Paalen, Wolfgang, ed. DYN. No. 1-6 (1942-1944).

Periera, Armando, Claudia Albarrán, Juan Antonio Rosado, and Angélica Tornero.“El Hijo Pródigo. Revista Literaria - Detalle de Instituciones.” Enciclopedia de la Literatura en México. Accessed March 26, 2024. http://www.elem.mx/institucion/datos/1848.

Sawin, Martica. Surrealism In Exile and the Beginning of the New York School. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995.

Strom, Kirsten, The Routledge Companion to Surrealism. New York: Routledge, 2023.

Su, Tsu-Chung. "Artaud's Journey to Mexico and His Portrayals of the Land." In CLCWEB: Comparative Literature and Culture 14, no. 5 (2013). Accessed April 22, 2024. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2151&context=clcweb.

Tate Modern. “Surrealism Beyond Borders.” 2022. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/surrealism-beyond-borders/exhibition-guide.