State-Level and Local Legislation

After World War II, two bills designed to make the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) permanent were defeated in the U.S. Congress as a result of the heavy influence of Southern Democrats’ opposition to federal programs aimed at uplifting African Americans. The FEPC faced continuing opposition and was ultimately dissolved in 1946 under Harry Truman’s presidency. Meanwhile, interest blossomed at the state level, with bills introduced in 22 state legislatures in 1945 and 1946 for enactment of state-level fair employment practices. New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts were the first states to enact this legislation.

Best location in the nation for freedom from discrimination in employment…, circa 1951

While some states were unsuccessful in passing FEPC legislation, municipalities adopted an enforceable FEPC. For example in 1950, the city of Cleveland had their FEPC administered by the Community Relations Board, previously established in 1945. This pamphlet describes the Community Relations Board, the first of its kind, as chartered by the city council to advocate, educate, legislate, and refer unlawful employment practices for prosecution when necessary.

Employment on merit – report, circa 1951

Minneapolis was one of the first municipalities to establish an FEPC and corresponding policy on merit-based employment. This pamphlet is a report on accomplishments from the first three years of the Commission’s work, which began in 1947. The state of Minnesota, however, was not able to pass an FEPC law.

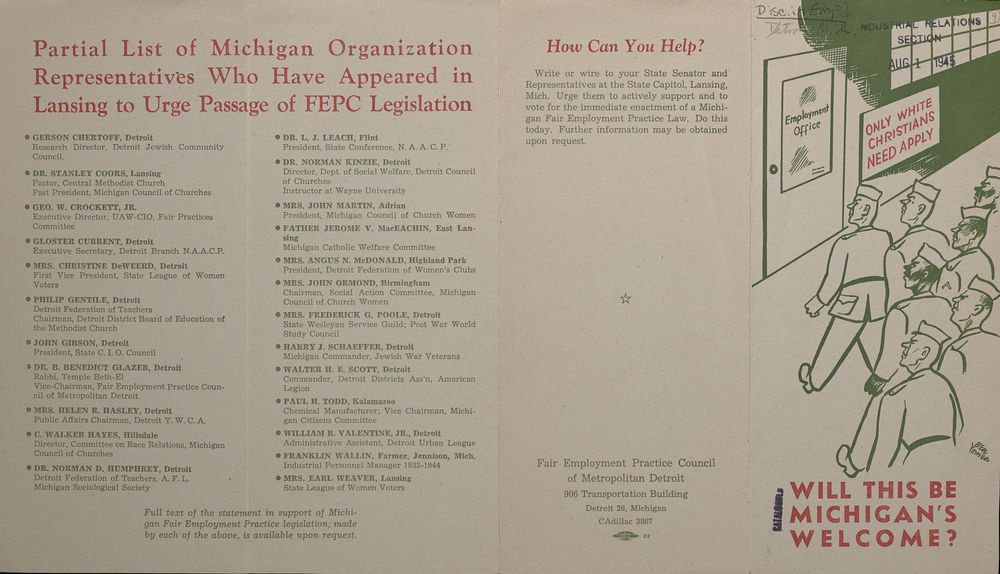

Will this be Michigan’s welcome?, circa 1945

Some states were unsuccessful in attempts to pass FEPC laws. It took Michigan 10 years after this pamphlet was published to pass their state FEPC law. By 1955, after many years of constant effort by labor organizers, only14 states had passed FEPC laws.

New Jersey’s law against discrimination, circa 1964

New Jersey’s law against discrimination dates back to 1945. However, in 1962 new requirements were added through age discrimination amendments. This pamphlet demonstrates the ways in which professional associations such as New Jersey’s Manufacturers Association, similar to labor unions, disseminated information about changes or updates to legislation pertinent to its members.