The Western Sublime: Manuscript Diaries of the Overland Trails

By: Brian Wright *23 and Kate Carpenter *24

Access digitized versions of the journals and diaries highlighted in this essay here, and find complete annotated transcriptions of each manuscript at the bottom of this page.

While some of the Western travelers featured in this project (like Stephen Gano and Thomas Adams) wrote long, detailed accounts of their journeys, many of the manuscripts in this exhibition are shorter accounts written by everyday travelers. These men traveled to join the California Gold Rush, to look for land and a new place to settle, or for temporary employment on cattle drives. Each overland party carried their own motivations for the journey, but each of these diarists were well aware of their role in the “development” of the region. Some wrote in fleeting bursts, recording little more than mileage and major landmarks; other authors were more reflective, plumbing their dreams and fears so far from home. Separately, the accounts highlighted here give us glimpses of individual experiences that might otherwise go unnoticed. Collectively, they give us a sense of some of the common concerns of Americans on the Western trail.

By mid-century, much of the region remained unmapped and foreboding to would-be settlers. Great promise and great danger lay ahead for any overland party. A common thread of these journals is a heady combination of wild optimism and paralyzing dread. This was the basic paradox of any colonial dream: riches or utopia or an escape from the status quo might be achieved only by braving the unknown and surviving primitive struggles with nature. As they went, the daily rigors of the journey and the scale of the landscape began to humble even the proudest settlers. Many of the writers began to appreciate all that they did not know about this place. What they did and did not record in their pocket-sized diaries and sheets of folded letters reminds us not only of the great distances crossed by wagon in those days but also of the distance between ourselves and the people of the past. The sensation they felt leaving home for unsettled points west is difficult to contemplate in our interconnected world. It was, for many of these writers, difficult to even put into words.

The Past — the dark unfathom'd retrospect!

The teeming gulf — the sleepers and the shadows!

The past — the infinite greatness of the past!

For what is the present after all but a growth out of the past?

“April 12, 1849. Left home for California, felt very sad for some time after leaving my wife and children. Morning fair, evening rainy.”

These are the opening lines of the journal of M.A. Violette, a “49er” setting out from Huntsville, Missouri for Gold Rush California. This was utterly typical of many journal entries in the genre: brisk, sad, always attentive to the weather. Some diarists were more stoic than others. Perhaps writing their most vulnerable, private thoughts would be too much to bear. Some openly longed for the families and places they left behind, and others were more enamored with the prospect of great adventure. William Brisbane, in his first diary entry after leaving Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, wrote that he “felt as if going out on a pleasure excursion instead of such a tramp as we are on…This is delightful.”

Most of these men left family behind: wives, children, parents. They came to see their overland parties as a new kind of family, stitched together by a mutual drive to reach their destinations in one piece. Some new families were christened, too: Brisbane witnessed an impromptu wedding beside the road after a group’s minister finished an especially stirring sermon. “It was truly a novel affair out here,” Brisbane wrote.

And yet many yearned for semi-regular contact with their loved ones, writing letters at any opportunity. David Starr Hoyt, en route to California in 1852, scribbled out a letter to his wife while his team briefly rested at Fort Laramie. Dexter P. Hosley noted in his diary that he’d “written home to my wife today and are going to put it in the office at ft Laramie.” “I have wished a thousand times to be at home,” Stephen Gano wrote to his parents from the California diggings. During a stretch in the mines without regular mail, Stephen grew almost desperate: “I have read no letters from Home,” he wrote, “and feel to be forgotten.”

Women became a rare sight in general. Anytime Hoyt spotted a woman along the trail, he wrote it down. On May 19, 1852: “Passed many women and children on the road today.” On May 23: “Saw a woman in camp churning butter.” On the trail, men tackled duties that might have been considered women’s work at home, especially cooking. Sometimes the results were disappointing—Brisbane complained of a burned bean stew one night—but other times they seemed to delight in their culinary endeavors. The day after Independence Day Brisbane crowed that he “astonished the camp with a Peach Pie.” But for bachelors like Brisbane, this was still not enough to replace the comforts he’d grown used to at home. “I turned over and fell into a most delightful doze,” he wrote of one night, “and most exquisite dream of home and someone—had a notion to hit Walker when he told me breakfast was ready.”

The thought of those they left behind propelled the men to finish the journey. Hosley, after earlier complaining about how slowly his group was traveling, reported that they had picked up the pace and “thought it best to harness up the teams and go on as fast as we culd as we all feel anxious to get through and be earning something for ourselfs and familys [sic] for we have already been 3 months on the way.” His entries became more anxious a few days later, as he wrote that “this road is getting long to me I tell you I want to get through and hear from my family and friends at home for I know that they are expected to hear from me any day but I shall get through by and by if patient.”

It’s worth noting that the landscapes through which these settlers trudged were often unlike anything they’d ever encountered. The Eastern seaboard’s predictable seasons, regular rainfall, and relative flatness had ill-prepared even the hardiest travelers for the soaring, jagged mountains, rushing rivers, and stark deserts of the Plains and Rockies. The allure and terror of this “wilderness” brought intense feeling to the surface of even the most stoic diarists from time to time.

B.F. Burche, traveling through what is now western Oregon, was left speechless at the views from the peaks of the Warner Mountains as his party dropped into California through Lassen Pass: “I turned my face westward & stood spellbound at the grandeur and magnificence of the scene,” Burche wrote. “We were standing several thousand feet above the plain, and could from the spot we occupied, have a full & uninterrupted view of the surrounding country for hundreds of miles.” David Starr Hoyt, making his way through what is now western Nebraska, saw the majesty of classical architecture, surely a touch from the gods, in clusters of rocks: “The scenery of the Gap in Scott’s Bluff is grand and magnificent,” wrote Hoyt, “presenting an amphitheater of rocks whose rugged surface represent with singular truthfulness Towers, Forts, steeples, and buildings of all forms and rises.” William Brisbane, taking a shot at the Santa Fe trail, couldn’t believe how the endlessness of the Plains morphed so suddenly into the vastness of the Rockies: “The snow clad hills of Mexico burst upon our view,” he wrote, “and a more beautiful sight I never witnessed—the country has completely changed and we now are among the mountains who height exceeds conception. The monotony of the plains is broken.”

The Western wilds were beautiful, sure, but they were terrifying too. Most of these settlers had little idea where they were or what was coming next. The unknowability of it all made danger and doom ever-present. No one would arrive to save you if you took the wrong fork in the road or ran out of water. And these settlers ran out of water constantly.

One anonymous diarist, describing his journey on a cattle drive from Fort Laramie to California, described this predicament early into the trip. On Saturday, June 29, 1850, he wrote, “We left the river at 10 A.M. and entered upon a long stretch of 26 miles upon which our cattle will get no grass or water. The country is as barren as a desert, there being nothing of the vegetable kind except the wild sage.” David Starr Hoyt alternated in his descriptions of the landscape from pleasant fields of flowers to “desolate looking country” seemingly devoid of life. Arizona Territory struck Chester King as “the refuge of disappointed lovers,” and he believed that “only thieves, thugs, outcasts and criminals come here." Clouds of mosquitoes followed parties for days, swarming their camps deep into the night. “We are annoyed all day by clouds of mosquitoes,” wrote Hoyt, “that torment men and horses until 9 o’clock at night.” William Brisbane lamented in one entry how he and his party “were attacked today by a swarm of mosquitoes—never saw and never expect to see the like again. Every man and horse was covered with them on the leeward side.”

The less inviting elements of the Western environment could take a toll on such interlopers. But overland parties also tended to run roughshod over trails in their haste, and wrought their own devastation. Even some of the earliest migrants of the 1840s were stunned by the damage left in the wake of forward parties. One afternoon, the anonymous cattle driver’s party “passed large numbers of dead cattle and horses, besides others left to die on this dreary waste.” On September 19, 1849, B.F. Burche was struck by the “number of dead and dying oxen on road” and appraised the destruction as “incalculable.” He added bitterly that “on the whole road, not a blade of grass.” Later in his journal, passing through another dry stretch, the cattle driver wrote that “the cattle lost upon this stretch (without water) would, in saleable order, in the states, enrich a whole country…The river is lined with their carcasses and the bottom land is covered with them.”

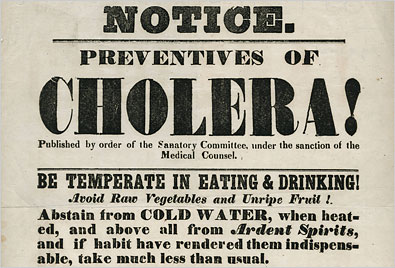

Death was not reserved solely for the cattle and the pack animals. Cholera hung in the air and terrorized traveling parties. It became almost routine for settlers to pass unmarked graves, victims of the deadly virus. “Several fresh graves that we passed had no mark at all,” wrote Hoyt, “excepting the smooth mound of fresh earth; while others had pieces of board set in the ground, on which were written with ink or chalk, the name age and late residents of the occupants.” Hoyt was especially unnerved, adding that “it is sad thus to find disease and death at work so soon and so fearfully on this long and tiresome journey.” “Passed one new Cholera grave this P.M.,” wrote the cattle driver without comment. A few days later, one of their own party, a Mr. Danforth, was “violently attacked with cholera & now lives in a very precarious state.” Danforth survived the ordeal, but only after the party was forced to halt for several days and watch 2,000 head of cattle—to these cowboys, cash on four hooves—pass them by.

Hoyt’s group encountered another train that lost an Irish immigrant to cholera. Hoyt helped bury the man alongside a creek, and reported that he left his wife, his children, and his brother. Not mincing words, Hoyt described the way the woman, who had slept with her children alongside the corpse, cried as they lifted the body away. The suddenly widowed woman was inconsolable: “The wife’s grief was violent and almost turned hysteric when we began to shovel in the each around the body, but it was somewhat allayed when I stepped into the grave and enclosed the head with green leaves.”

A month into their journey, one of the members of M.A. Violette’s company made a grisly discovery: “Mr. George Haines found a dead man who look as though He Had bin dead a week.” The next line was even darker: “We passed a man Dying to day who shot him self by Taking His gun out of His wagon loaded. Also another Just ahead who shot Him self the same way and died.”

This collision of intense beauty and impending doom was perhaps the defining experience of the overland trails. Venturing into the “Great West” could be a great adventure, one of world-historic significance; or it could be a personal disaster, a hare-brained scheme turned into tragedy. In the midst of his discomfort on the trail, Dexter P. Hosley clung to the promise of what lay ahead in Gold Rush California: “I am all covered with the dust, not the gold dust but the dust of the earth,” he wrote. “But we are slowly progressing towards the Shining dust.” Meanwhile, when the anonymous cattle driver found himself separated from his group for a long and sleepless night, he recorded in his journal this chilling entry:

"There was nothing to be seen but the vast expanse of land and sky, each colored with the same dull leaden tint of night; no horizon was visible, not a star appeared, and, in the midst of this gray monotony, a stillness prevailed that smote my heart with something more appalling than mere fear. No storm that I ever listened to, or the loudest thunder, ever chilled my blood like that terrible stillness. I cannot picture to you the wild and lonely solitude of these barren plains."

Something deeper than “mere fear” stirred the cattle driver to such profound despair on that starless night. Poets and philosophers had since the eighteenth century called this mixture of awe and fear the “sublime,” a realization of man’s smallness in the universe, his helplessness in the face of nature’s indifferent cycles of destruction and regeneration. The conservative English scholar Edmund Burke called the emotional response to sublime things "Astonishment": “The passion caused by the great and the sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is Astonishment,” he wrote, “and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.”[1] The English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote that the sublime was more than simple beauty; it was what happened when something beautiful offered a glimpse into the enormity of the universe and its mysterious laws. “The circle is a beautiful figure in itself,” wrote Coleridge. “It becomes sublime when I contemplate eternity under that figure.”[2]

To these settlers, the West was terra incognita, the Great American Desert, a “virgin land.” As an object of contemplation, it embodied both beauty and fear. The region contained a cosmos they could not yet begin to comprehend. Walt Whitman, the bard of industrial America and an eloquent booster for westward expansion, admitted man's smallness in the face of nature: "Swiftly I shrivel at the thought of God, / At Nature and its wonders, Time and Space and Death."[3] Against these odds, having acknowledged nature's indifference to the whims of man, these westward migrants felt their success would confirm national destiny and their own personal gambit to start over "out there." The sublime, then, could be achieved not through mere reflection but by rough, direct action. In "Pioneers! O Pioneers!" Whitman sang of the settlers' physicality and resolve in the face of danger: "We take up the task eternal, and the burden and the lesson ... Down the edges, through the passes, up the mountains steep, / Conquering, holding, daring, venturing as we go the unknown ways, / Pioneers! O pioneers!"[4]

Whitman translated the anxieties of strung-out families on the Plains into small tales of national triumph. Even some of the travelers themselves found the region inspiring for art. “If I were only an artist," wrote Chester King, "what happiness I’d have sketching the beauties of these mountain gorges.” It was sublime—beautiful and terrifying, all at once—to roam through this "frontier" while the places these settlers had called home, all that they’d ever known, had long since fallen into the eastern horizon.

Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?

The West seemed unknowable, too vast to contemplate, and yet it was not some empty landscape that simply refused to speak. The region’s indigenous inhabitants were, to most of these settlers, perhaps the most persistent source of mystery and fear throughout their journeys. Rumors of Native American ambushes fill many of these pages, even if most of these writers only fleetingly interacted with the original stewards of the land.

A series of entries from the anonymous cattle driver in July 1850 are typical. On July 11, after splitting off with another man to chase down a lost horse, he wrote that “we learned that the Indians had committed several depredations upon the emigrants and about an hour before sundown I thought it advisable to start on horseback in pursuit of our company.” A few days later, he reported that his company was keeping a close eye on their cattle because “the Indians are very troublesome in this vicinity. They surprised the guard of another company last night and drove off 80 head of cattle.” And a few days after that: “We are informed that a large party of Snake Indians drove a company of Californians from this place this morning.”

Indian thievery became a common thread of Anglo small talk along the trails, however bogus or overblown.[5] Even by the early 1880s, Chester King realized that local settlers still hadn't figured out how to track Indian movements. “The Indians,” King wrote, “are at present an unknown quantity and it is impossible to tell where they are or what they are doing.” Duplicity and sudden violence became the basic context for nearly all interactions, accidental or otherwise. The cattle driver, on his first true encounter with a member of the Snake tribe, recorded it this way:

"We were this morn visited by an Indian (one of the Snakes) who was on a fine gray horse—one undoubtedly stolen from some of the emigrants. He informed us (as well as he could) that the Indians ahead were very hostile & would kill us, but we heeded not his talk for he was hungry and to earn his lunch, he thought he must give us some information."

The assumption that this “fine gray horse” was stolen speaks volumes. William Brisbane wrote of Natives they met at the trading post Council Grove with the same prejudice: “notorious as thieves,” he said of the Kaw Indians, “and the most vagabond and worthless tribe in the world. They are as expert pickpockets (as some of the party have discovered already) as our Gentlemen of the states.” While camped in present-day New Mexico, Brisbane reported that “we are surrounded by the Navahoes [sic] now and we are all on the ‘qui vive’ expecting them to attack us tonight and attempt to steal our mules.” When nothing materialized overnight, he believed that “the rascals were afraid to come.” The next day, Brisbane and the rest of the party thought they had let their guard down when their grazing mules suddenly started running. “The cry of Indians was raised and everyone, dragoons and all…started in pursuit.” It turned out they had not been attacked after all; nervy horses had provoked the mules to stampede.

Others took a more sympathetic approach to their Indian interlocutors. Dexter P. Hosley, en route to California from St. Joseph, Missouri in 1852, wrote that his party “saw Snake Indians today” and noted that “they are very friendly.” David Starr Hoyt described encountering a group of “Kickapoo” Indians standing by the side of the road: “They dressed principally in the poor cast off garments of white men and appeared melancholy and dejected. They presented us a slip of paper on which the United States Indian Agent for their region had certified their peaceable character with the fact that the passage of Emigrant waggons [sic] through their country had injured them by frightening away the wild game on which they depend for food and requesting all emigrants to make them some trifling compensation in money.” Hoyt’s group obliged, giving them the requested 25 cents per wagon, but Hoyt perceived the group as more like beggars than toll operators: “Many emigrants pay no attention to the poor creatures and even insult them.”

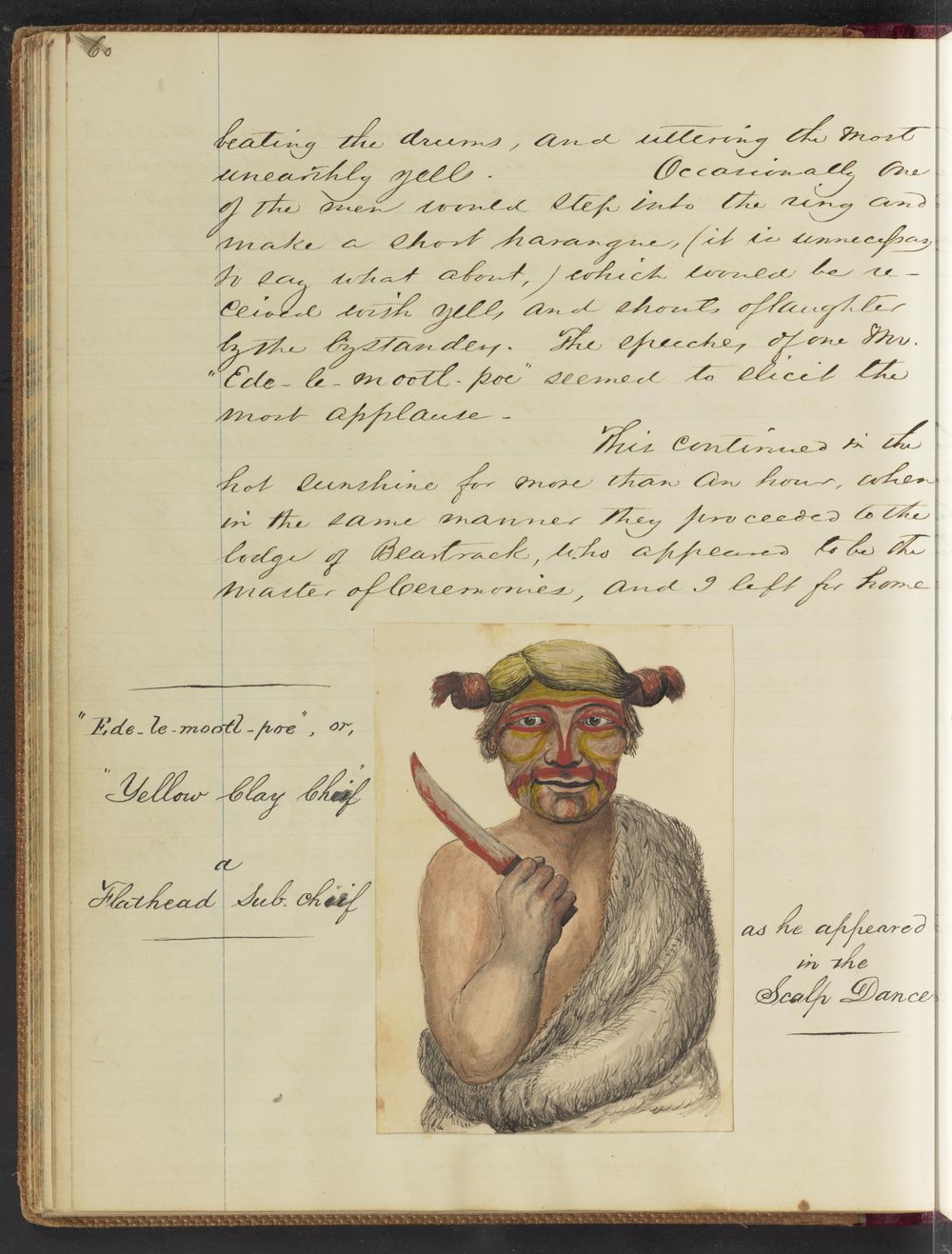

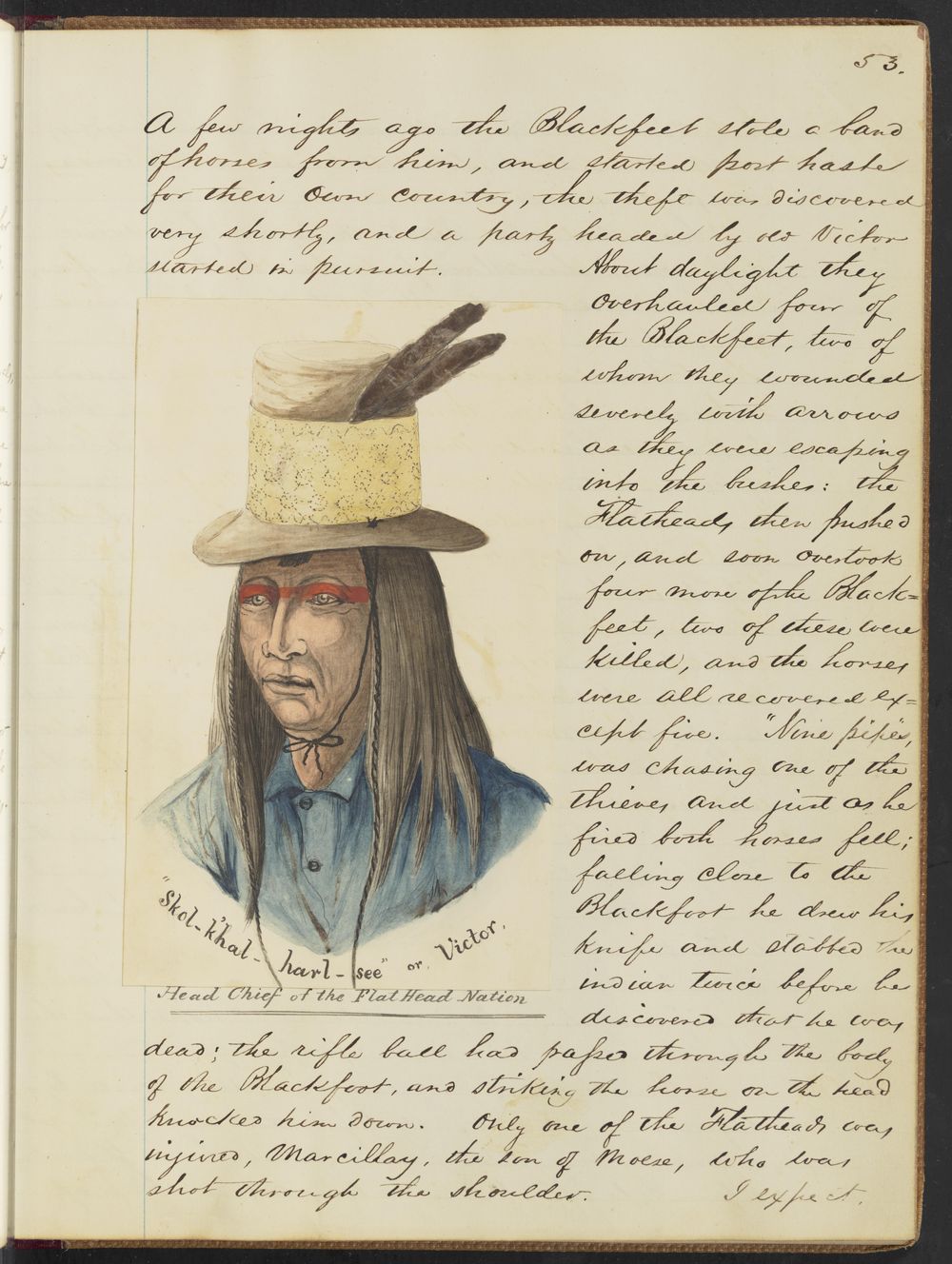

Any healthy rapport that developed between the settlers and Indians usually emerged from mutual necessity. Native scouts guided hapless Anglo parties through treacherous mountain passes and across the featureless plains. Meeting grounds like Council Grove and Santa Fe offered migrant parties basic supplies, lodging, entertainment, and rarer goods from extensive continental trade networks. And there were, to an extent, moments of cultural exchange, faulty but fascinating attempts to bridge chasms of sensibility and understanding.

At one point, Brisbane’s party encountered “150 lodges and about 800 Indians” gathered to meet. He reported that the Indians were friendly and curious about the travelers: “even now while sitting in the wagon writing a dozen are examining my California shoes.” They also traded – “Traded my neck kerchief for a splendid rope plaited of buffalo hide. They don’t know the value of money.” He reported that they were members of the Arapaho tribe; they met another group the next day. Brisbane’s diary entry about them drips with condescension, concluding with the note: “amused myself trying to make an Indian say, ‘Yes siree Bob.’”

These glimpses at Native American life offered by the journals present an object lesson in the powers and limits of archival material. We have here pages and pages of anxious scribbling about Native Americans—imminent raids, nighttime theft, their social rituals, the occasional amusing anecdote—and yet nothing comes to us from the Indian subjects. Where is their testimony? What did they make of these light-skinned interlopers in their lands? Did this Indian man trying to pronounce “Yes siree Bob” also find it so funny?

Nineteenth-century Indian life is not some mysterious blank, and it is not unknowable. But the Native American experience of the West's "frontier" period often presents itself in written documents only obliquely—written by outsiders or foes, laced with racist language, molded by ignorance and prejudice. For a generation or two now, historians have worked hard to read between the lines of the written record for the indigenous side of the story. And this is not to say that no manuscript material exists to illustrate the Native past. For its part, the Princeton Collections of the American West feature thousands of nineteenth-century photographs depicting Indian life in the West. Archivists and curators across the country are beginning to connect more meaningfully with Native communities to highlight, share, and repatriate historic tribal material held by museums and libraries. And rather than dismissing Indian material cultures and oral traditions, historians are now eager to pair written material with a variety of Native media—calendar sticks, winter counts, origin myths—to better traverse the rich interpretive crossroads of folklore and history.

And yet we remain tethered to the surviving remnants of our past. Perhaps only a fraction of the journals and letters that westering migrants wrote across the nineteenth century eventually survived the long and winding road to our time. The Euro-American mind requires these kinds of documents to achieve an "objective" or "authentic" version of the past.[6] To Indian historians, the search for objectivity is both futile and totalitarian. Objectivity forecloses narrative flexibility and exaggerates man's place in the universe. "Ultimates and absolutes belong to the gods," writes anthropologist Peter Nabokov of Indian historiography, and "it is as hopeless to search for any single, authoritative ur-narrative as it is to look for paradise."[7]

Our understanding of our own history depends, perhaps perilously, on testimony that has been selectively and incidentally bequeathed to us by our forebears. These settlers, recording their western experiences, considered the Indian world they were invading essentially unknowable—or a world not worth knowing. All Americans, but especially Native Americans, continue to live with the consequences of westering Americans' actions: conquest, displacement, cultural suppression. But we also must live with these settlers' inaction, with what they did not care to discover or describe. Once the mountain passes and rolling deserts and dense forests had been mapped and re-named and considered "known," the West's greatest mystery remained, to most Anglo-Americans, the Indian universe they tried to replace. As awe-inspiring as these settlers may have found Scott's Bluff, or Monument Valley, or any of the West's unique geological formations, they never quite grasped the sublime vastness of the human world all around them.

[1] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (London: printed for R. and J. Dodsley, 1757).

[2] Thomas M. Raysor, “Unpublished Fragments on Aesthetics by S. T. Coleridge,” Studies in Philology 22, no. 4 (1925): 532–33.

[3] Walt Whitman, "Passage to India," in Leaves of Grass (1892 edition).

[4] Walt Whitman, "Pioneers! O Pioneers!" first published in Drum-Taps (New York, 1865).

[5] Glenda Riley, "The Spector of a Savage: Rumors and Alarmism on the Overland Trail," Western Historical Quarterly 15 (October 1984): 43.

[6] On the search for objectivity in American historiography, see Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

[7] Peter Nabokov, A Forest of Time: American Indian Ways of History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 47.

Annotated transcriptions of the manuscripts highlighted in this essay: