Astronomy and Atomic Science

Sid Lapidus, like so many of the historical figures included in this exhibition, had many interests. His collection is notable for its focus on the Enlightenment era, but has some notable works on developments in atomic science of the 20th century.

Interestingly, the astonishing insights into the inner workings of the atom can be traced from the refinement of the scientific method in the 18th century. The famed English physicist Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727) insisted on close observation using the senses, rather than reliance upon ancient writings, to ascertain knowledge. As scholars gained practice in this mode of thinking, they also developed finer and finer instrumentation, able to ascertain the invisible motions of the tiniest particles.

From earlier detailed observations of astronomical phenomena to the detection of cosmic rays, the Lapidus collection—in works concentrated in the New-York Historical Society and the American Antiquarian Society—offers glimpses of the progression from the astrolabe to the spark chamber.

Unless otherwise indicated (§), all items on exhibit are from the Sid Lapidus '59 Collection on Liberty and the American Revolution, Princeton University Library. All items on loan from other libraries are gifts of Sid Lapidus.

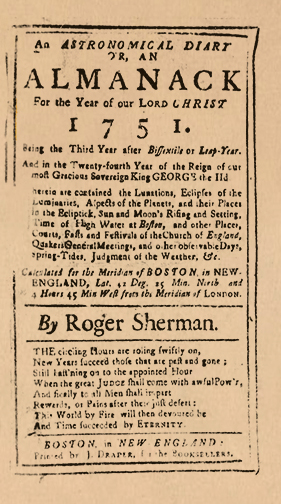

An Astronomical Diary: Or, Almanack for the Year of Our Lord Christ, 1751: Calculated for the Meridian of Boston, New-England, Lat. 42 Deg. 25 Min. North, 1750

Nathaniel Ames (1708–1764)

Boston: Printed by John Draper

Almanacs were among the most widely circulated printed materials of the 18th century. Providing information about “Eclipses; … Spring-Tides; Judgment of the Weather; … Sun and Moons’ Rising and Setting; Times of High Water,” they were vital for farmers planning their agricultural work for the year. Such information was scrupulously calculated using a tool called the astrolabe to observe and predict the position and movement of the sun and stars.

On loan from The New York Historical, New York

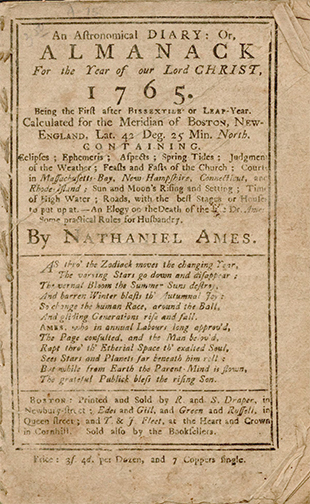

An Astronomical Diary: Or, Almanack for the Year of Our Lord Christ, 1765: Calculated for the Meridian of Boston, New-England, Lat. 42 Deg. 25 Min. North, 1764

Nathaniel Ames (1741–1822)

Boston: Printed and sold by Richard and Samuel Draper

Nathaniel Ames Sr. and Jr. carried on a family tradition of almanac-making. The younger Ames was politically minded and used his popular almanacs to urge his readers to embrace self-sufficiency, reject aristocracy, and in the exhibited passage, be alert for the “quacks” offering ineffective medical remedies “without one Qualification.”

Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Bannaker's Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and North-Carolina Almanack and Ephemeris for the Year of Our Lord 1796, 1795

Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806)

Baltimore: Printed for Philip Edwards, James Keddie, and Thomas, Andrews and Butler

Benjamin Banneker, a free Black man, taught himself astronomy and surveying strictly by reading books on the subjects and watching the skies. He is famous for helping to survey the District of Columbia, after which he ventured into almanac-making. His 1795 Almanack illustrates that astronomy and astrology had not yet entirely been separated, as this illustration depicts the influence of heavenly bodies positioned within the constellations upon individual body parts.

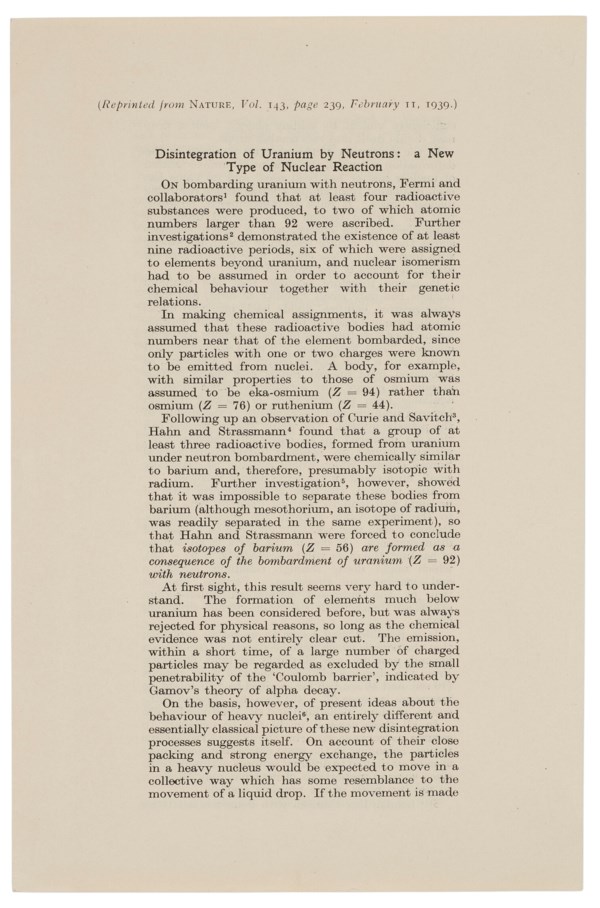

Disintegration of Uranium by Neutrons: A New Type of Nuclear Reaction, 1939

Lise Meitner (1878–1968) and Otto Robert Frisch (1904–1979)

London: Macmillan & Co.

Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, Austrian-born physicists, learned in 1938 that German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann had bombarded uranium with neutrons, producing barium. They realized that the nuclei of uranium atoms could split apart. Their publication of this—the first use of the word “fission” in the context of atomic science—in the February 11, 1939, issue of Nature launched a new science which culminated in the explosion of atomic bombs in 1945, and the development of nuclear reactors for civilian electricity in 1954.

On loan from The New York Historical, New York.

A General Account of the Development of Methods of Using Atomic Energy for Military Purposes under the Auspices of the United States Government, 1940-1945, 1945

Henry De Wolf Smyth (1898–1986) - Princeton University Class of 1918

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

Henry De Wolf Smyth was a professor of physics at Princeton. He consulted on the development of atomic bombs. The “Smyth Report” he wrote immediately after World War II shared declassified information about the origins and development of the bomb, and was a best-seller for several months. Its focus on physics (slighting metallurgy, chemistry, and weapons-making) shaped postwar perceptions of the project. Controversially, the report revealed exact locations of the plants where atomic materials were manufactured (even though this was not classified information, some critics felt it was better left unpublicized.)

On loan from The New York Historical, New York

The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946

United States Army Corps of Engineers, Manhattan District

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

While the unleashing of atomic energy was in one sense a question of science, its practical application was military. While less deadly overall than the bombing of Tokyo in March 1945—which required fleets of airplanes—the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (August 6 and 9) was far more efficient, requiring one air crew and one bomb per city. Here, the Army assessed the destructiveness of atomic bombs, complete with visual evidence.

On loan from The New York Historical, New York

The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946

United States Strategic Bombing Survey

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

Atomic bombs were the final technical development in a policy called “strategic bombing”: Allied air forces dropped munitions on whole cities in Germany and Japan with the intention of destroying manufacturing capacity and reducing civilian morale. The Strategic Bombing Survey was a 316-volume report assessing the effects of strategic bombing. In this volume, the board of experts who prepared the survey reviewed atomic bombs. The atomic bombs were not the last bombs to be dropped—Allied air raids continued until V-J Day on August 15.

On loan from The New York Historical, New York

Photographs of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946

United States Army Corps of Engineers, Manhattan District

Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office

On loan from The New York Historical, New York

The Philosopher Reading a Lecture on the Orrery, 1768 §

William Pether (around 1738–1821), from a painting by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

Mezzotint

A tool of astronomers in the 18th century was the orrery (named for Charles Boyle, 4th Earl of Orrery, who commissioned the first one in England.) An orrery is a mechanical model of our solar system, showing the relative position and motion of the planets, moon, and sun as they orbit. The College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) had one in Nassau Hall, the main building on campus in the 18th century, from 1771 to 1776, when it was damaged by troops, both British and American, who were housed there.

Astrolabe (modern reproduction), between 1986–1996 §

Sterling silver

Astrolabes are astronomical instruments that allow users to calculate and predict the observed motion of planets and stars in the sky. They are known from the ancient Greeks and were in widespread use until the invention of the sextant in the 1750s. This modern reproduction was a gift to the library from Mario Soares, President of Portugal between 1986 and 1996.

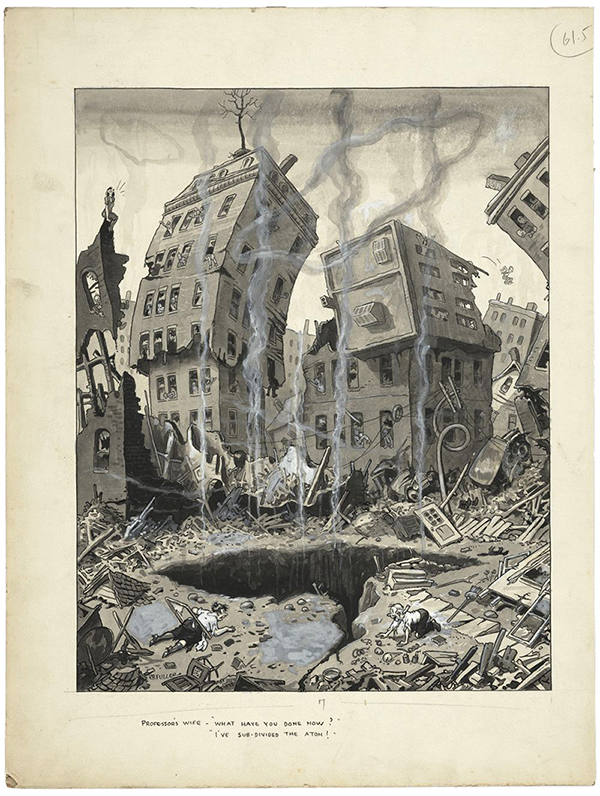

Professor's Wife, “What Have You Done?” “I've Sub-Divided the Atom!”, 1926 §

R. B. [Ralph Briggs] Fuller (1890–1963)

Pen-and-wash drawings, gouaches on board

American cartoonist R.B. Fuller prepared this drawing, which was published in the humor magazine Judge in 1926. As early as 1919, the renowned physicist Ernest Rutherford was attempting to “break up the atom,” but of course not in his home office!