Igor Savchenko and His Works

During his prolific career, Igor Savchenko produced a diverse body of artworks, including textual and mixed media projects, multiple photo-series and single photographs. Over the years, he excelled at combining semantic minimalism with representational deficiency: his images are strikingly suggestive and just as strikingly non-transparent.

Savchenko’s signature style was developed in the 1990s during his active engagement with readymade photo-objects—found or bought images—that he exposed to multiple visual alterations. Photo-objects of the past were appropriated in a somewhat slanted way, helping to situate Savchenko’s own authorial presence indirectly yet prominently.

In his study of the Minsk School of Photography, Serguei Oushakine termed such visual techniques of figuration “vicarious photography” to highlight both the ready-made nature of its sources and the type of indirect subjectivity that it portrays. Vicarious photography grants “the power of speech” to “an absent, deceased or voiceless entity.” [1] Its goal is to seize a mask or a face as a vehicle for surfacing the presence of the unseen in familiar narratives and histories.

These acts of enmasking could be read as a particular form of postcolonial appropriation through which Minsk photographers critically resuscitated and redeployed visual languages of the Soviet period. Similar to more traditional sites of postcolonial experience, the new states that emerged after the dissolution of the Soviet Union—postcolonies of Communism, indeed - face the same fundamental question: how to engage with the colonial past without enabling its structure of subjectivation.

Postcolonial appropriations are not just another instance of the process through which reality—mythical or otherwise—is packaged in historically available metaphors; they are also forms of mimetic resistance. In the postcolony, techniques of appropriation are tools of re-signification, which offer subaltern groups “possibilities for ‘talking back’ to and through the categories that have been created to contain” them. [2]

Since many photographic projects of the Minsk School of photography activated photo-objects of the past, this “secondhand” photography could not document or objectify the photographer’s own gaze. But it could foreground the syntactic and rhetorical conventions that helped vicarious photographers perform their acts of mimetic resistance.

Created retrospectively, these postcolonial archives of the period that is past rely on visual analogues of reported speech, demonstrating their constitutive dependency on premediated forms of expression. [3] The derivative quality of this visual production is not unproblematic, yet it vividly exposes such “paraphrasing” devices as re-focalization, re-sequencing, and tonal flattening, through which the available visual legacy is recalled, recaptured, and rearticulated.

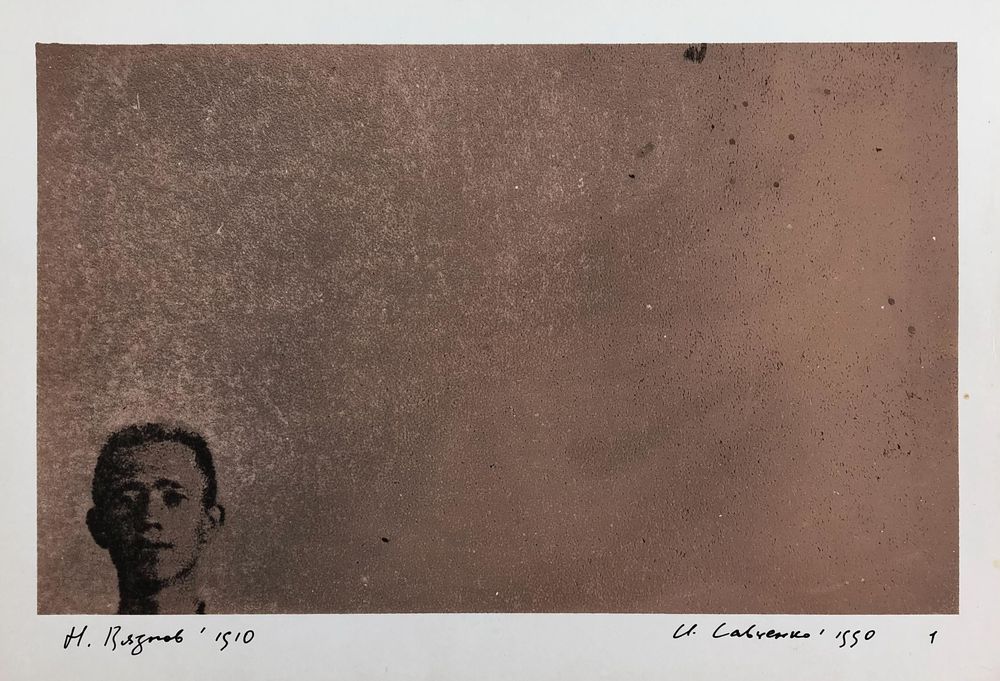

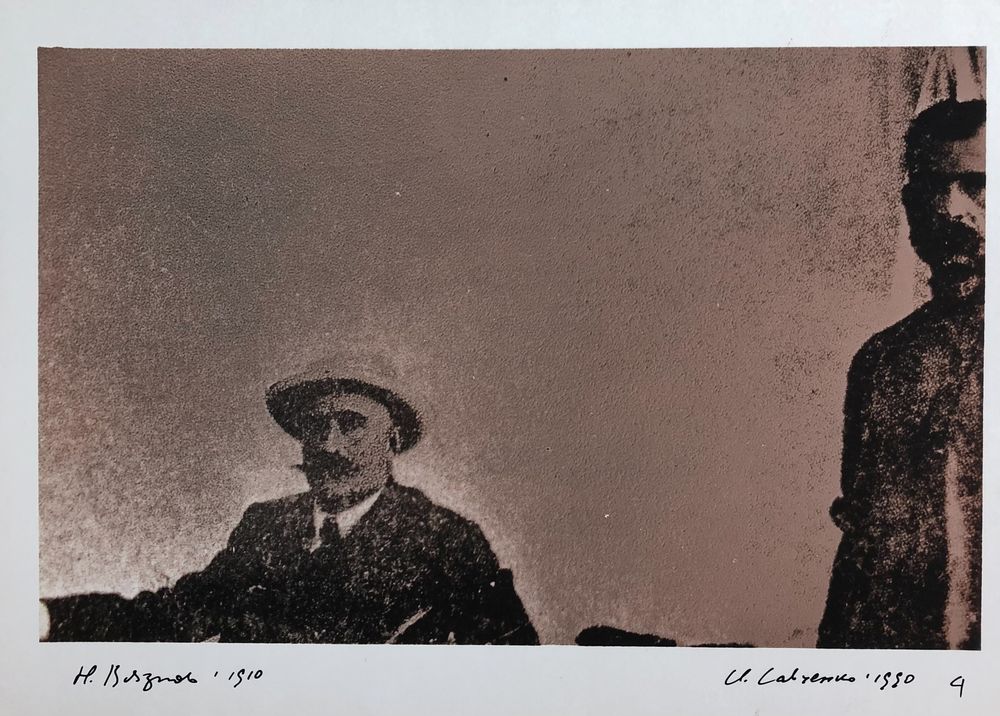

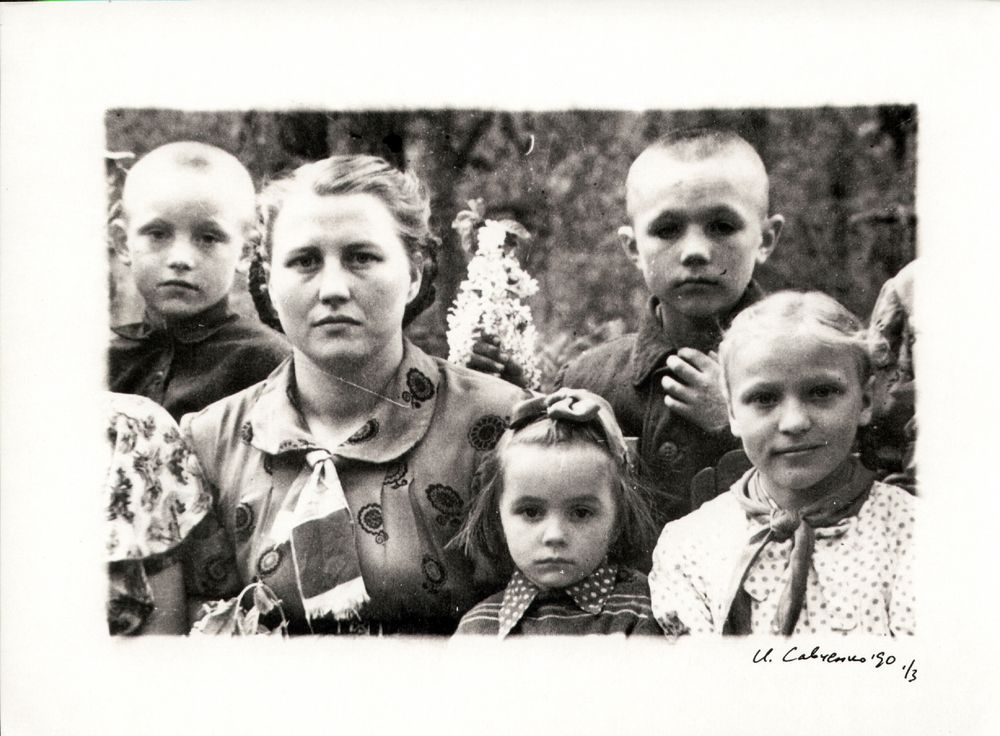

A single photo, sequentially segmented. From the photo-cycle N. Viaznov. 1910. 1990

The vicarious photography pioneered by the Minsk School allowed presence without identification. Its play with stereotypes offered a way of recycling visual formulas of the past while simultaneously providing artists with expressive possibilities for demarcating their authorial non-alignment with these formulas.

Their emptied subjects—defaced but camouflaged—persistently demonstrated the structuring power of the costumes. Blurring the distinction between appearance and substance, these photographers presented subjectivity as a vocabulary of outfits and poses that could deliver meaning even when the identity of the performer could not be established

The past in these photographs was decontextualized and reduced to its material indices. This reduction, however, was not necessarily an operation of historical flattening, but rather a mode of transcoding. History was approached as a storehouse of ready-made pieces that could be reactivated, reassembled, and reappropriated. In place of memory there were mnemonic objects, and facts became overshadowed by what Russian avant-garde artists of the 1920s called faktura—that is, by the tangible characteristics of historical artifacts, their textures, colors, shapes, and sounds.

Savchenko’s projects embody the major aspects of vicarious photography in the most comprehensive way. He amalgamates photography and graphic art, producing images that are simultaneously austere and uncanny.

Like many of his colleagues, Savchenko creates series and sequences. However, the open structure of his sets often makes their “serial” quality rather questionable, and Savchenko prefers to call them “cycles,” emphasizing the returning (rather than linear) character of his engagement with each group of images.

With very few exceptions, his photographic cycles do not date the “originals.” Instead, they offer the artist’s signature and the year of the image’s second “birth.” The time of origin, in other words, is re-coded as the time of the original’s creative appropriation. Strikingly, Savchenko’s cycles offer little individualizing information about the portrayed subjects, too.

Anonymity is the default choice, and history is approached mostly as an assemblage of decontextualized historical types, outlines, or imprints. Torn out of their temporal and historical settings, these secondhand photographic records are reclassified by the artist under whimsical rubrics: Alphabet of Gestures; Shadows; Faceless; Mysteria; About Love; About Happiness, etc.

Externally imposed narrative axes reorganize newly recorded historical traces, suggesting a highly curated picture of the past. "Counter-documentary” in nature, these visual records “no longer belong to anyone, or, on the contrary, they belong to everybody who could remember. [4]

Perhaps like no one else among his peers, Savchenko developed an elaborate vocabulary of techniques that modified and recomposed available visual narratives. In addition to such usual dermoplastic gestures as blurring, overpainting, and scratching, he would also submit found originals to various forms of optic (pre-digital) manipulation.

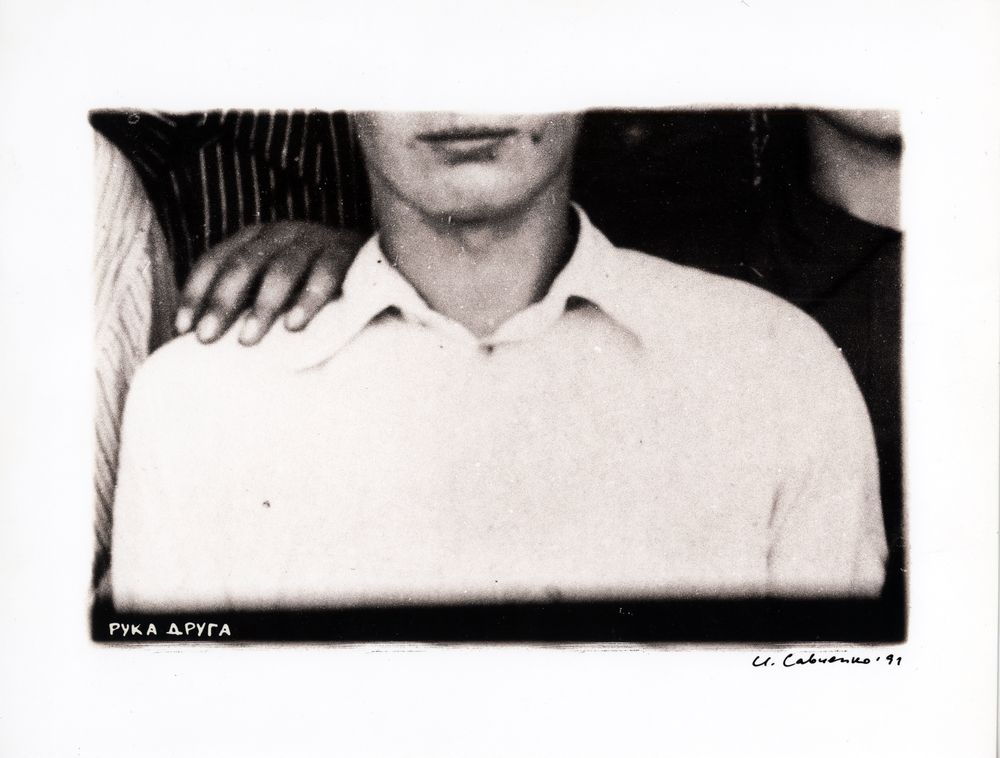

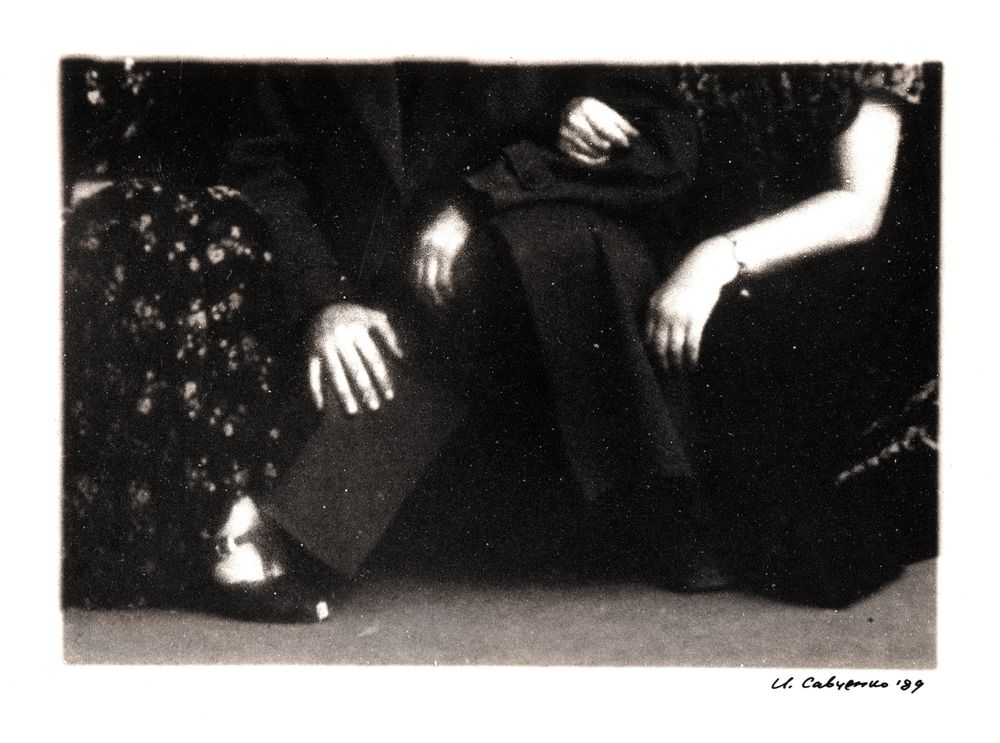

For instance, his Alphabets of Gestures (1989–94) were created through a sequence of rephotographing sessions, during which a found photograph would be enlarged and cropped multiple times so that a minor detail from the original could reemerge as a new focal center of he frame. Historical records were subjected to a rigorous inspection.

All images in the cycle presented a fragment of an individual or a collective portrait, but instead of focusing on the subjects’ faces, Savchenko zoomed in on their hands or legs. Enlarged and cropped, the final frames depicted acts of complex gestural communication, reimagining the past as an intensely haptic experience of anonymous somatic configurations.

Turning peripheral elements of the portrait into the centers of attention, the cycle documented the nuanced choreography of extremities that is often overshadowed by more noticeable facial expressions. When seen together, Alphabet’s gestures offer a strange spectacle of the body, familiar and alienating at the same time.

The photographic fragments clearly came from static public portraits. However, in their de-faced and magnified incarnations, these hieroglyphs of limbs suddenly disclose the fetishistic nature of attempts to approach the historical detail too closely, converting the alphabet of gestures into the voyeur’s archive.

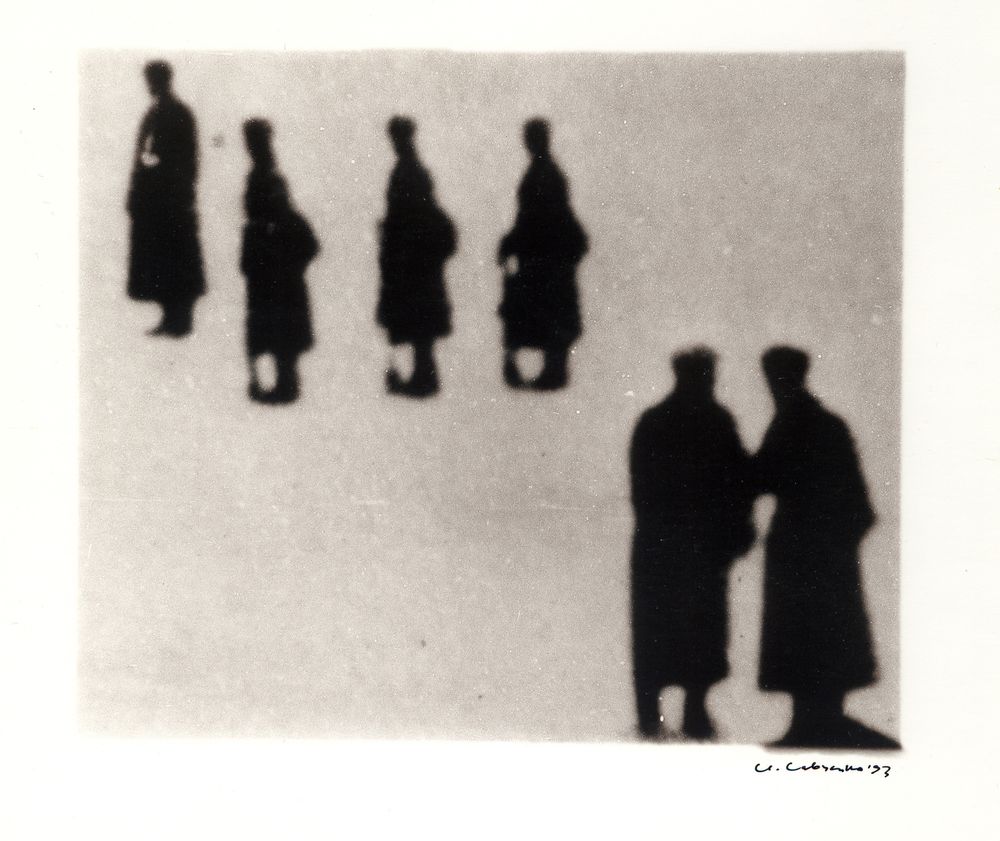

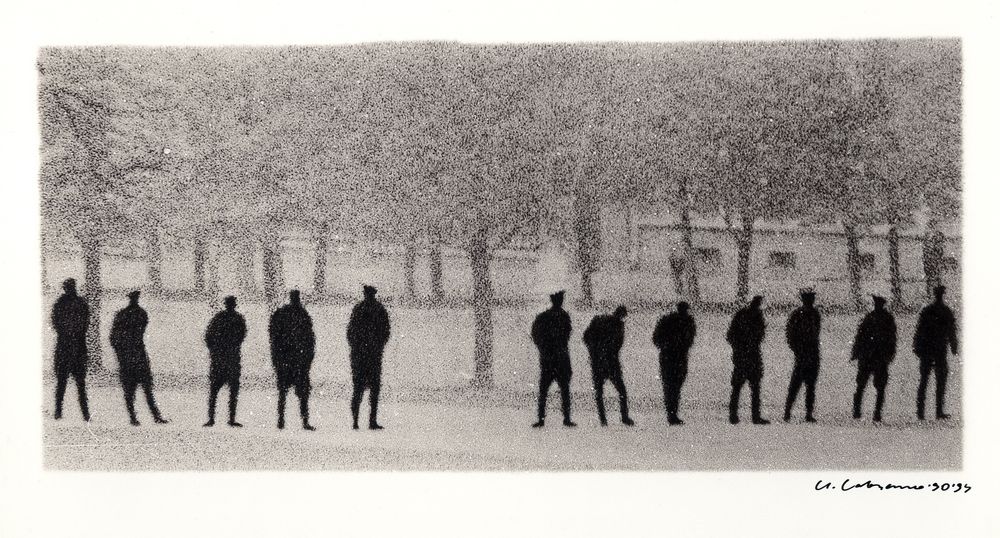

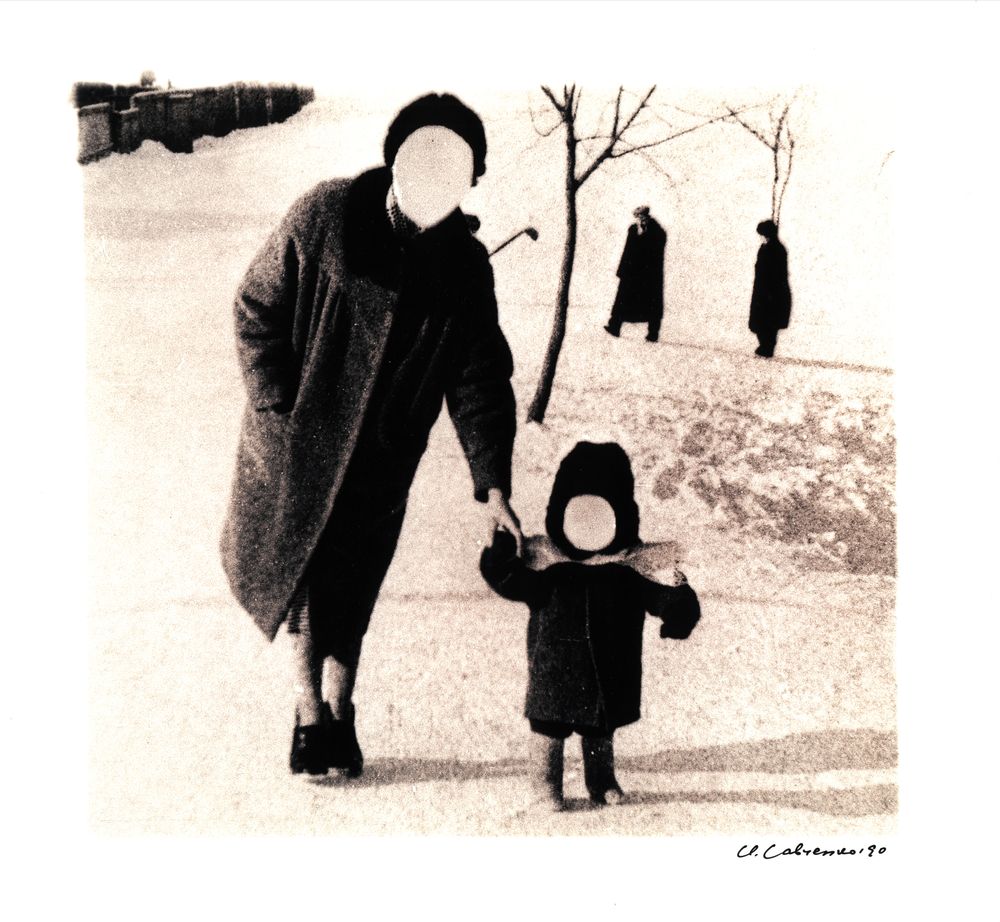

Savchenko’s Shadows and Silhouettes (Teni, 1989–93) offered a more complex syntax of working with borrowed visual formations. The cycle included toned photographs in which individuals or groups were placed within empty, grainy environments. Figures were “lifted” from different sources and then recombined and “laminated” as a single frame through multiple exposures.

In some cases, Savchenko punctuated the photographic space with flat, dark figures borrowed from other photographs to create a rhythmic sequence of almost identical silhouettes. In others, the frame was occupied only by a single individual. In yet others, he assembled black humanlike cutouts in a linear sequence that echoed the row of trees in the background, leaving the center of the frame unpopulated.

As with many other cycles, Shadows provided no hint about the original sources from which Savchenko borrowed the figures to populate individual frames. All traces of the figures’ possible pictorial kinship have been meticulously suppressed.

In the cycle, the images do not reveal their genealogy, nor do they coalesce into a new version of the systemic portrait. History, Savchenko seems to be saying, is not about origin. Here appropriation is a process of alteration. Yet it is crucial that these vicarious techniques do not retrofit representational remains of the past with contemporary content, as was common, for instance, for many photographic projects in Russia in the 1990s. [5]

The postcolonial reappropriation of historical frames in vicarious photography is not synonymous with the appropriation of history. Control over the process of representation is assumed through the control over the process of photographic reinscription; the remedy is discovered in the method of re-vision and recomposition.

Breaking the analogous relationship between images and their subjects, this form of appropriation undermines the basic assumption about photographs’ ability to “convey evidence that can lead back to the body that created the imprint.” [6] A photographic version of Plato’s cave, Shadows and Silhouettes envisions the past as a collection of corporeal imprints whose provenance and identities are unknown.

Shadows of history indeed, these anonymous bodies turn the past into a landscape of ghostly somatic outlines, into a space colonized by recognizably human contours but unrecognizable individuals. Again, figuration here is purposefully not self-explanatory. As if giving up all pretense of referential representation, in Shadows Savchenko activates photographic records of the past to demonstrate their ultimate failure to go beyond a simple reminder that the past has been there, as Barthes famously remarked. [7]

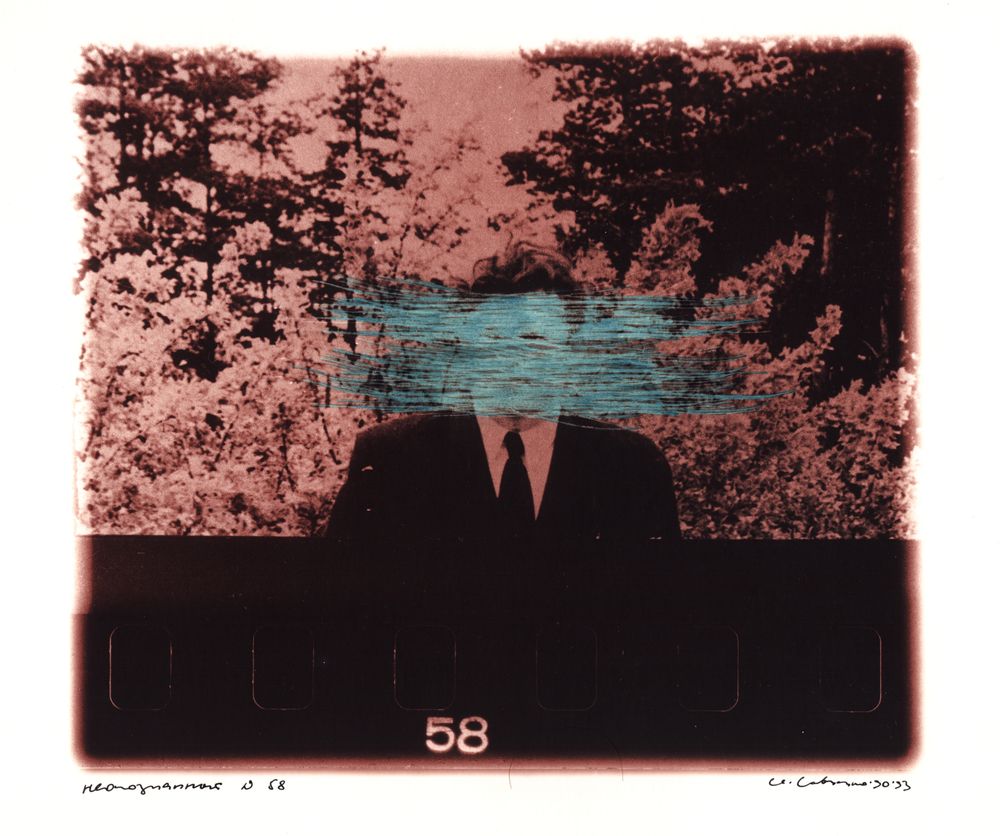

Six cycles of Savchenko’s Mysteries straddle the flattening distance of Shadows and the fetishistic obsession of Alphabets. In addition to cropping and refocusing, in this series Savchenko also overpainted found photographs. His Mysteria-1 (from the late 1980s) contains a set of portraits with epidermic interventions pointedly emphasized by the color red: dots and lines of various thickness and intensity cover the background and people’s figures.

As Savchenko clarified in an interview, in most cases he used paint only to highlight already existing cracks and scratches. As he put it,

For me, these defects of the originals were . . . traces of time, traces of those elemental forces of the period. There was something powerful going on back then. Hence the red color as the most appropriate in my view.

Some images are also accompanied by a handwritten caption at the bottom of the margin. The result is an intricate palimpsest of layers of appropriation: a cropped image of an acquired photograph that has been rephotographed, painted over, narrativized, dated, and signed.

Through this layering Savchenko establishes a noncommittal relation with the past, which is manifestly distanced while being imprinted with graphic marks of adoption. The adoption is more formal than substantive, and the allegedly clarifying “caption”—“ . . . yes, of course; but it doesn’t mean that the Last Judgement doesn’t exist”—does little to clarify the nature of the artist’s intervention. But like the red paint, it does chronicle the act of intervention. If the photo’s origin as a found object effaced the authorial self, then multiple tactical occupations of the photographic space reinstated the authorial presence, albeit in a non-transparent and obfuscating way.

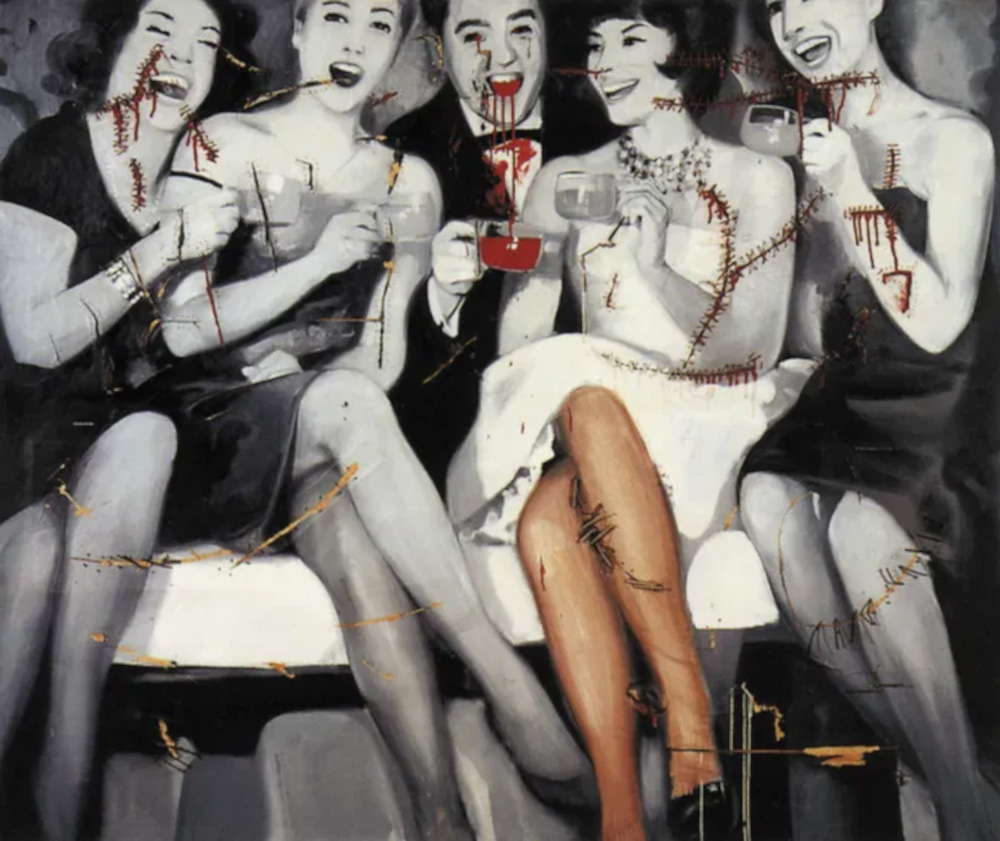

It is useful to contrast Savchenko’s work (and his explanation) with a painting by Gerhard Richter, one somewhat similar from the point of view of its technical characteristics. Richter’s Party (1963) is a painted reproduction of a photograph from the Neue Illustrierte, in which four glamorous women and a man drink punch, smiling at the camera.

While recreating the photograph, Richter substantially “corrected” the original. In the painting, people are covered with bloody scars. The scars are not merely illusionistic; they are physical cuts in the canvas, which have been stapled, stitched up, and painted over with bright red. Analyzing the painting, Eckhard J. Gillen reads the slashes and bloody additions as an example of capitalist realism, as materialized signs of Richter’s critical distancing from the content that he (re)created. [8]

Savchenko’s painterly incursions do not seem to have any obvious critical message. His overpainting refocalizes the image not by offering a counter-narrative but by amplifying “the faktura of the time.” Enhancing his authorial presence, he retraces the “elemental forces of the period” that have influenced the photo-object’s life and brings them to the fore.

What Richter’s work helps to illuminate, then, is the different status of borrowed formations in the Minsk School’s projects: The goal of vicarious appropriation is not to antagonize found objects pictorially (with blood) or physically (with cuts) but to use them as manifestations of substitutive presence.

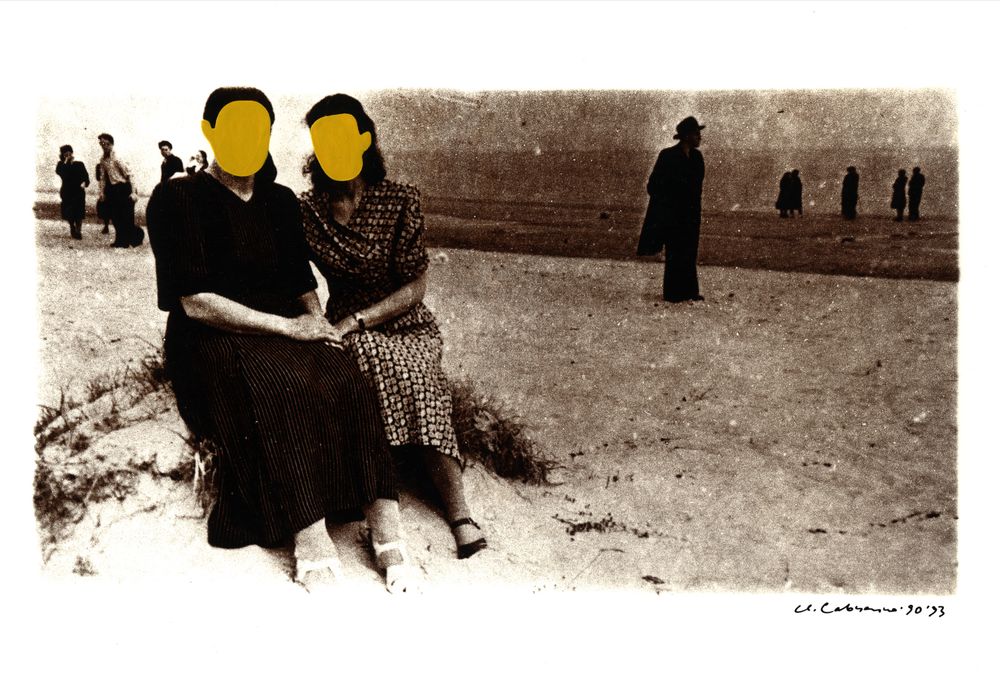

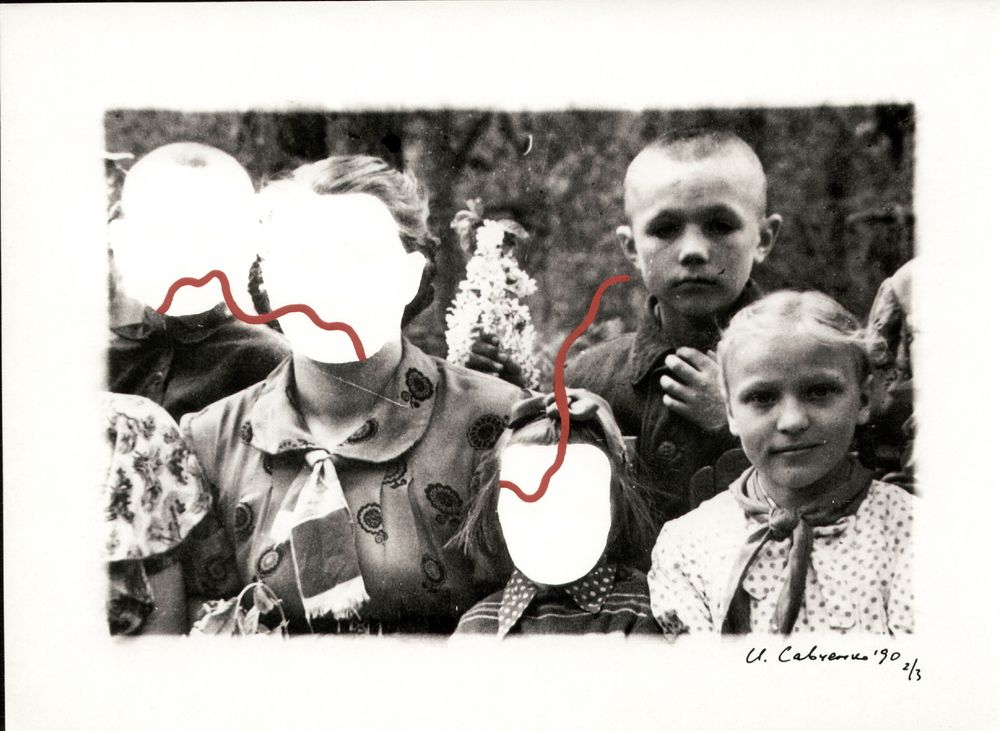

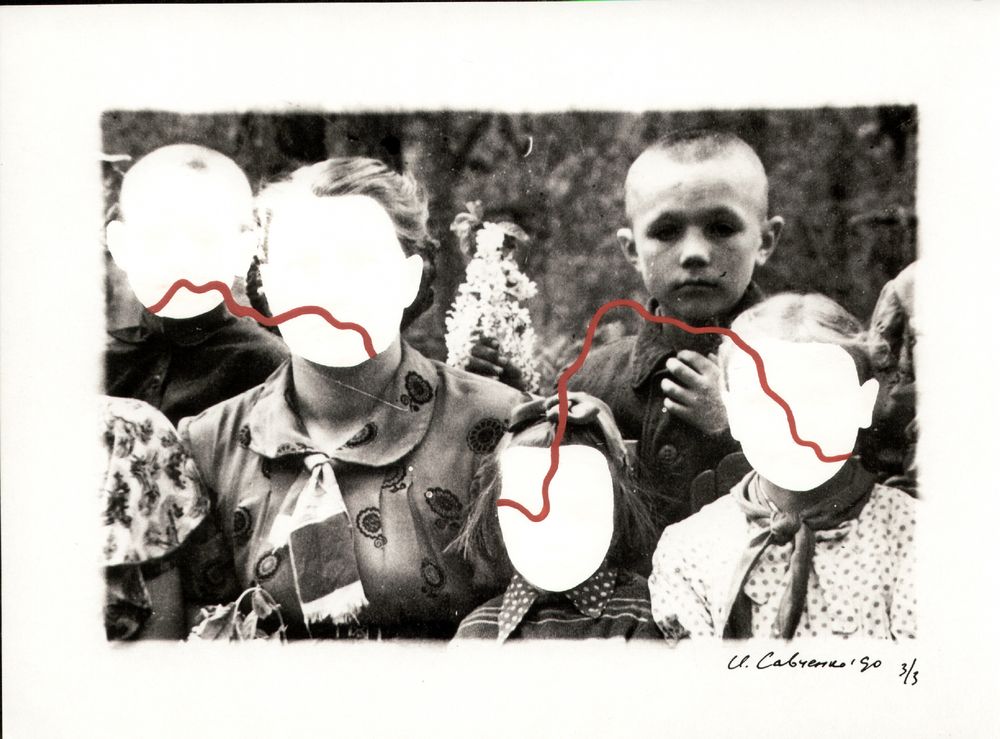

This attitude comes through especially vividly in Savchenko’s Faceless (1989–1991). The cycle includes mini-series and single portraits in which faces of many individuals have been completely hollowed out by being painted over. In Faceless, the directionality of enmasking is completely reversed: De-facement is utilized as a device for establishing and forefronting the unknown retrospectively.

Five Faces with Little Bouquets. 1990

Several mini–cycles chronicle a gradual erasure of facial features from one frame to another. Adding some visual dynamism, Savchenko marks sites of “de-facing” with a red line, as if authenticating the deletion. While there is nothing particularly sinister about the overall compositions or photographic content of these series, the traces of disappearance do produce a disturbing effect. The facial erasures are not total—hair, for instance, remains—and these sites of a surgically exectued non-presence look like entry points into another dimension beyond the picture.

When several works from the cycle were exhibited in 1994 at the Gallery of Contemporary Art at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, as part of a larger show, Monuments and Memory: Reflection on the Former Soviet Union, Savchenko’s work was presented in the show’s catalogue as a reminder about those who were made to disappear from history.

Savchenko was seen as a delayed incarnation of Aleksander Rodchenko. In 1937, Rodchenko was compelled to blacken out faces of people he himself had photographed earlier––out of “the necessity to remove from the archives any reference, including artworks, that would substantiate the prior existence of those made ‘persona non grata'.’” [9]

Fifteen years later, during an interview in Minsk, Savchenko completely dismissed this interpretation. Like many of his colleagues from the Minsk School, he privileged the indexical at the expense of the biographical, claiming that the political reading of his cycle had “nothing in common” with his own intention. “These people are faceless because these are human models,” he insisted. “They present different models of people in different life situations. Therefore, there are no faces. Just mother as such. Or child as such. They are types. . . . [The cycle is] about a universal human being [chelovek voobshche].”

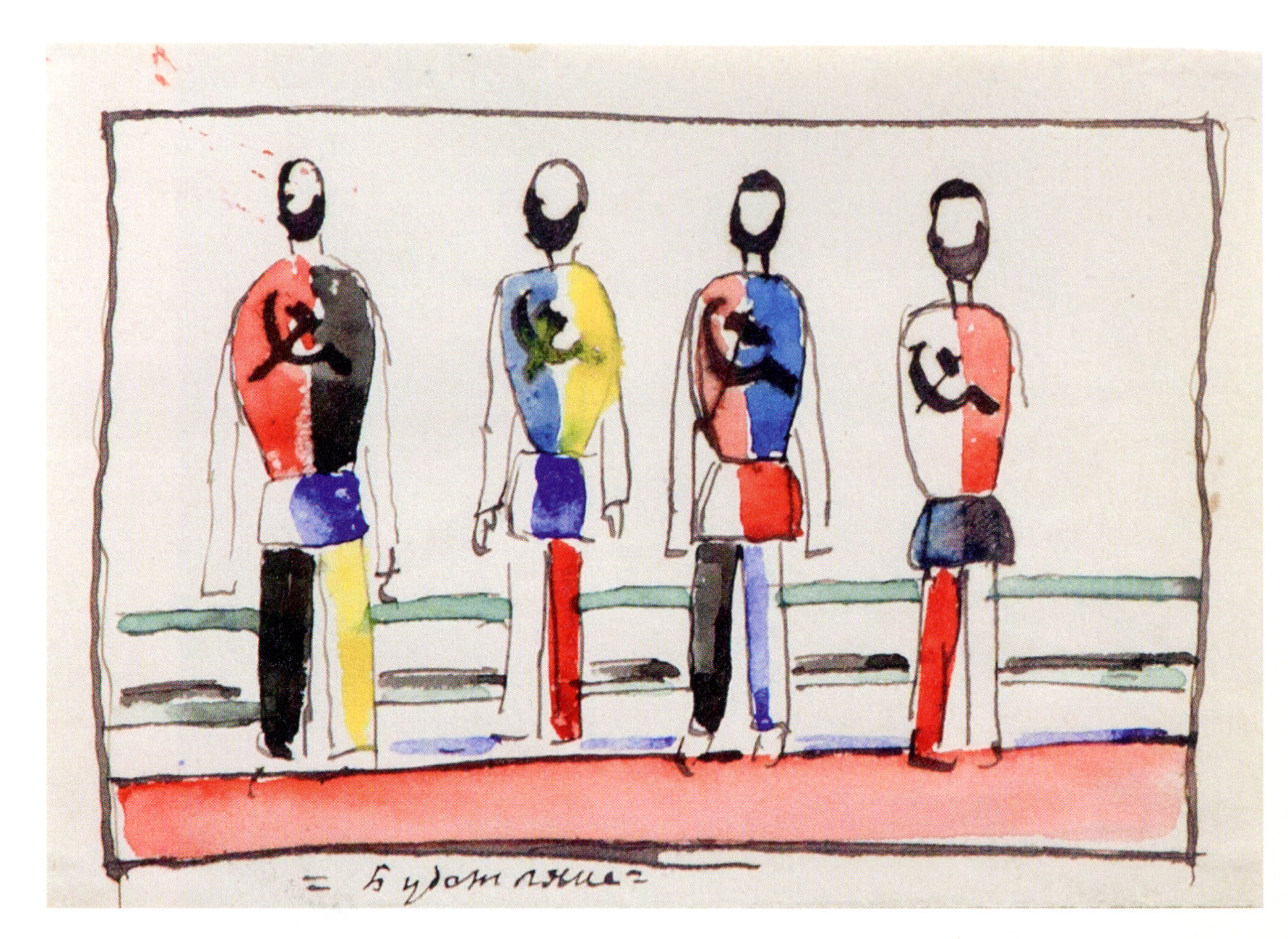

There is no reason not to believe him. After all, when, in the late 1920s and early ’30s, Kazimir Malevich was forced to abandon his cubes and circles, he switched to producing Peasants, Girls, and The People of the Future, whose personalities were similarly hollowed out. Faceless and deindividualized, they were also supposed to represent universal human types and social categories: shells to inhabit; models to emulate; outfits to try on.

Unlike Malevich’s generalized People of the Future, Savchenko’s “universal beings” of the past were not imagined; they were distilled and abstracted from historical records. However decontextualized and anonymized his “universal beings” were, they offered templates of an inhabitable past by pointing to experiences, situations, and relations that had been there.

In his cycles, Savchenko accumulated a collection of modalities that were instrumental for transforming ready-made history into material available for alterations and interventions. Through operations of fragmentation and recomposition, he refocused historical records. He also reactivated the available past by de-facing its subjects and retracing its elemental forces.

His art of tactical occupation did not produce an alternative version of history, but it did something more important. It unlocked “the substantialized ‘tower of the past’” and envisioned Soviet history as a space of new (visual) possibilities. [10]

Of course, there is a certain danger in replacing photography as a tool of documentary recording with photography as a speculative practice that relies on historical forms for building a foundation for hypothetical visions of the past. There is the clear threat of “the near complete disconnection of photography from social reality,” which makes lived experience appear “merely as a secondary effect of the photograph’s own creative fabrication.” [11]

Such disconnection does not have to take the shape of a flight from reality, though. As the visual archive of the Minsk School demonstrates, this distancing could also provide a necessary opening for generating forms of critical engagement with available photo-objects left behind by the vanished empire.

The Mink School practitioners of creative photography employed the visual language of the Soviet period to disassociate themselves from Soviet practices of photographic recording. By erasing subjectivity and abstracting imprints of lived experience, their vicarious photography articulated a model of dealing with history that allowed presence without identity or identification.

This text is an adapted excerpt from Serguei Oushakine’s essay “Presence without Identification: Vicarious Photography and Postcolonial Figuration in Belarus.” October № 164 (Spring 2018). Pp. 61-100).

[1] Paul de Man, “Autobiography as De-facement,” MLN 94, no. 5 (1979), pp. 925, 926.

[2] Faye D. Ginsburg, “Screen Memories: Resignifying the Traditional in Indigenous Media,” in Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, ed. Faye D. Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), p. 51.

[3] Valentin Voloshinov, Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, trans. Ladislav Matejka and I. R. Titunik (New York: Seminar Press, 1973), pp. 115–16.

[4] Olga Kopenkina, “The Picture Behind Him,” in Igor Savchenko: The Picture Behind Him (Rotterdam: Stichting Noname, 2001), p. 12.

[5] Serguei Alex. Oushakine, ‘We’re Nostalgic but We’re Not Crazy’: Retrofitting the Past in Russia,” The Russian Review, no. 3 (2007), pp. 451–82.

[6] Christopher Pinney, Photography and Anthropology (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), p. 68.

[7] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), p.76.

[8] Eckhard J. Gillen, “Painter Without Qualities: Gerhard Richter’s Path from Socialist Society to Western Art System, 1956–1966,” in Gerhard Richter: Early Work 1951–1972, ed. Christine Mehring, Jeanne Anne Nugent, and Jon I. Seydl (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010), pp. 72–73.

[9] Joseph Walker, “Monuments and Memory: Reflections on the Former Soviet Union,” in Monuments and Memory: Reflections on the Former Soviet Union, ed. Theodore C. Burtt (Fair field: Sacred Heart University, 1994), p. 16.

[10] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 2008), p. 201.

[11] T. J. Demos, “Recognizing the Unrecognized: The Photographs of Ahlam Shibli,” in Photography Between Poetry and Politics: The Critical Position of the Photographic Medium in Contemporary Art, ed. Hilde van Gelder and Helen Westgeest (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2008), p. 125.