PUBLISHING & PACKAGING

The prevailing format of the early nineteenth-century English novel was the "three-decker": a trio of handy octavo volumes, generally issued simultaneously, at a price that was affordable (but not cheap) for well-to-do readers. Exemplified by Sense and Sensibility (1811), which Jane Austen published anonymously and at her own financial risk, this format not only shaped the overall narrative and content of each volume, but made it easy for distinct volumes to be distributed among multiple readers within families and through lending libraries.

Another successful publishing strategy was the serial publication of novels in weekly or monthly installments. This approach was introduced with Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719-20) and attained renewed popularity in 1836 with the astounding success of Charles Dickens' Pickwick Papers. Just as established newspapers could promote untested novels, new works by successful authors could sell newspapers. For readers, the serialization of portions of novels in paper wrappers reduced the cost of reading and offered the option of binding up the novel once all the fascicles had been issued. Two immensely successful serialized novels are exhibited here in their original parts: Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1852), and Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871-72).

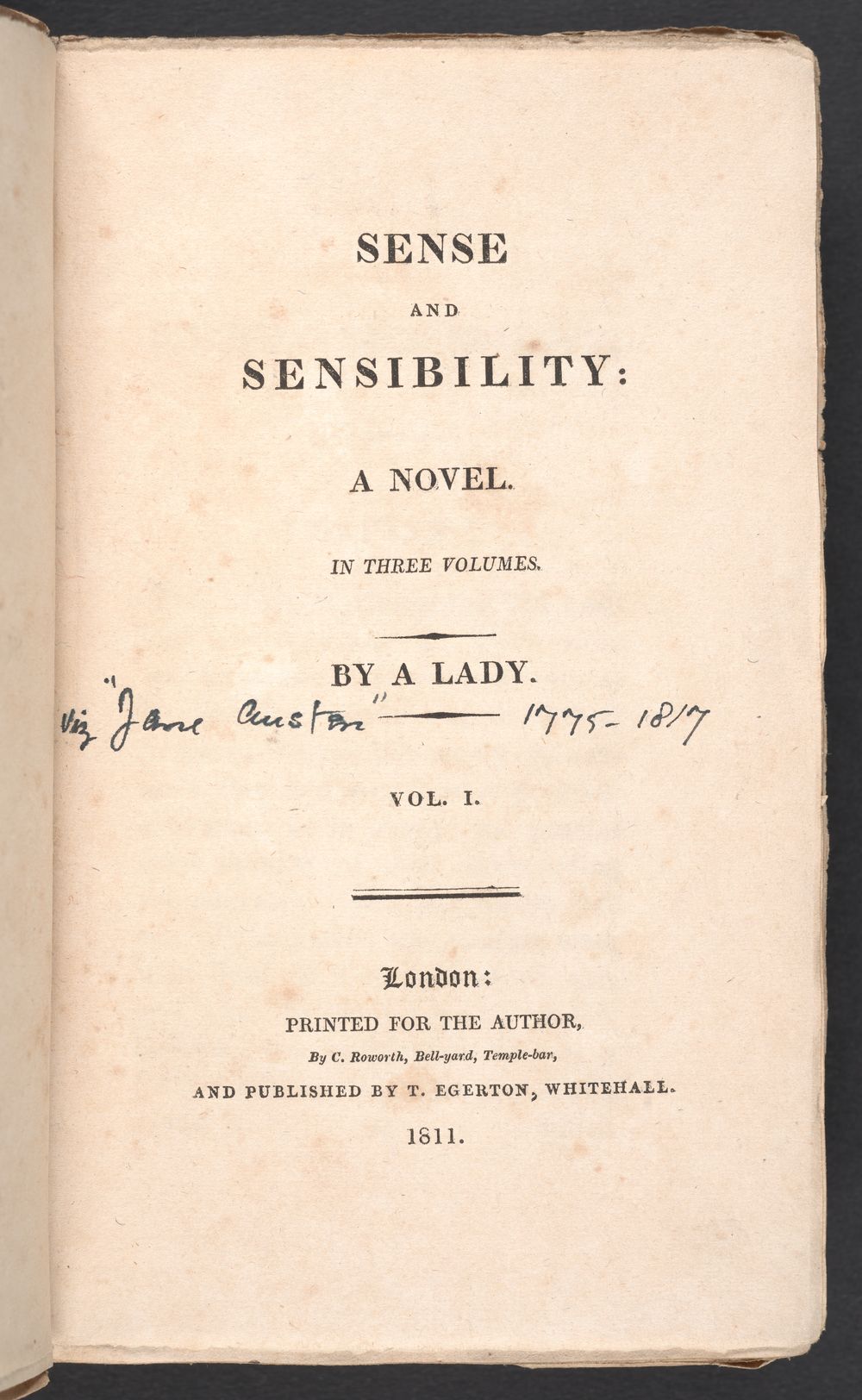

[Jane Austen (1775–1817)]. Sense and Sensibility. A Novel. 3 volumes. London: for the author, by Thomas Egerton, 1811. Robert H. Taylor, Class of 1930.

“Extraordinary Novel”: Jane Austen’s authorship of her novels was revealed only after her death in 1817. Advertised in London’s Morning Chronicle on November 9, 1811 as “by Lady ⎯” and published that day as “by a lady,” this “three-decker” was so successful that Austen’s subsequent novels were marketed as “by the author of Sense and Sensibility.” An owner of Princeton’s copy entered Austen’s name and dates on the title page.

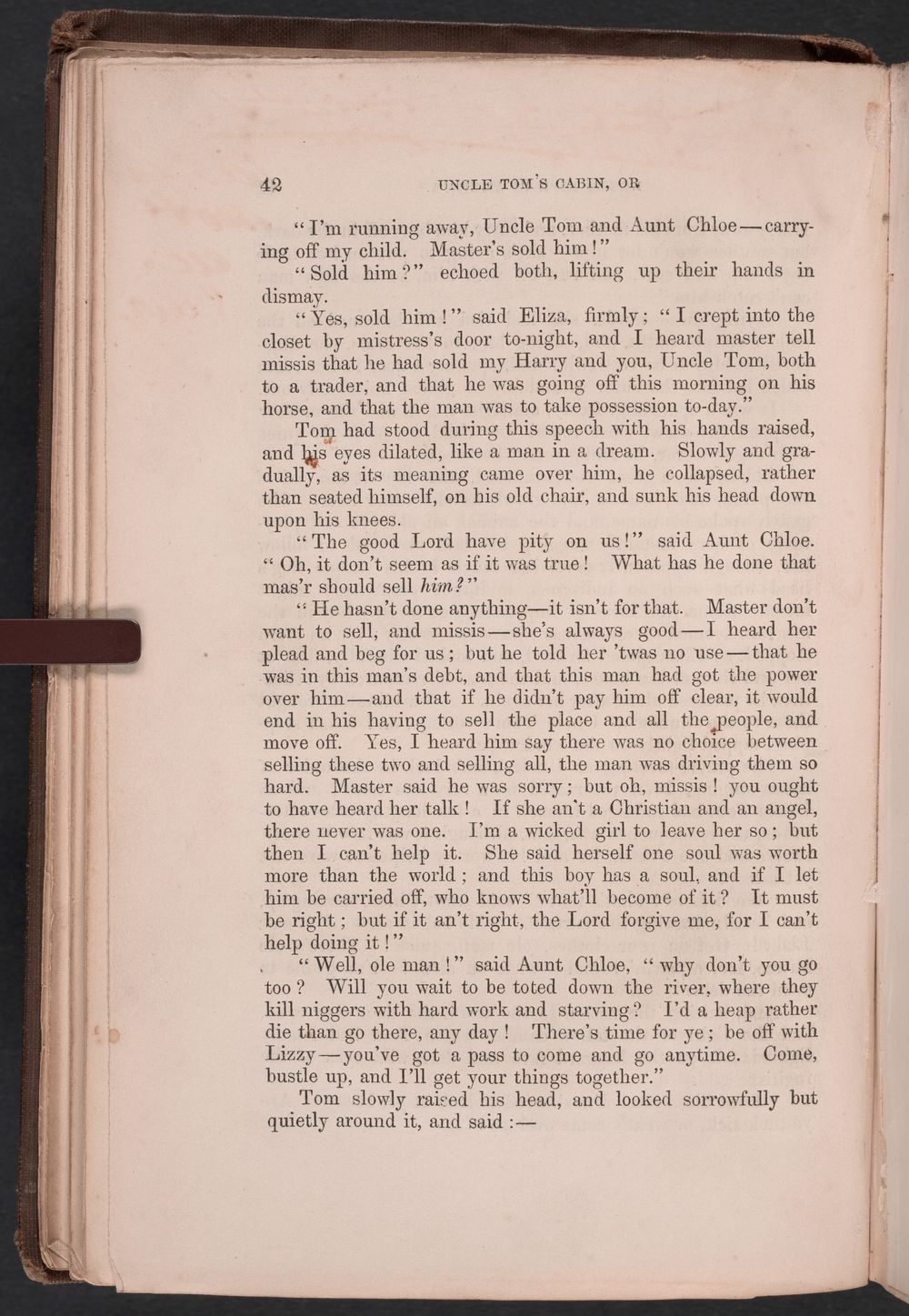

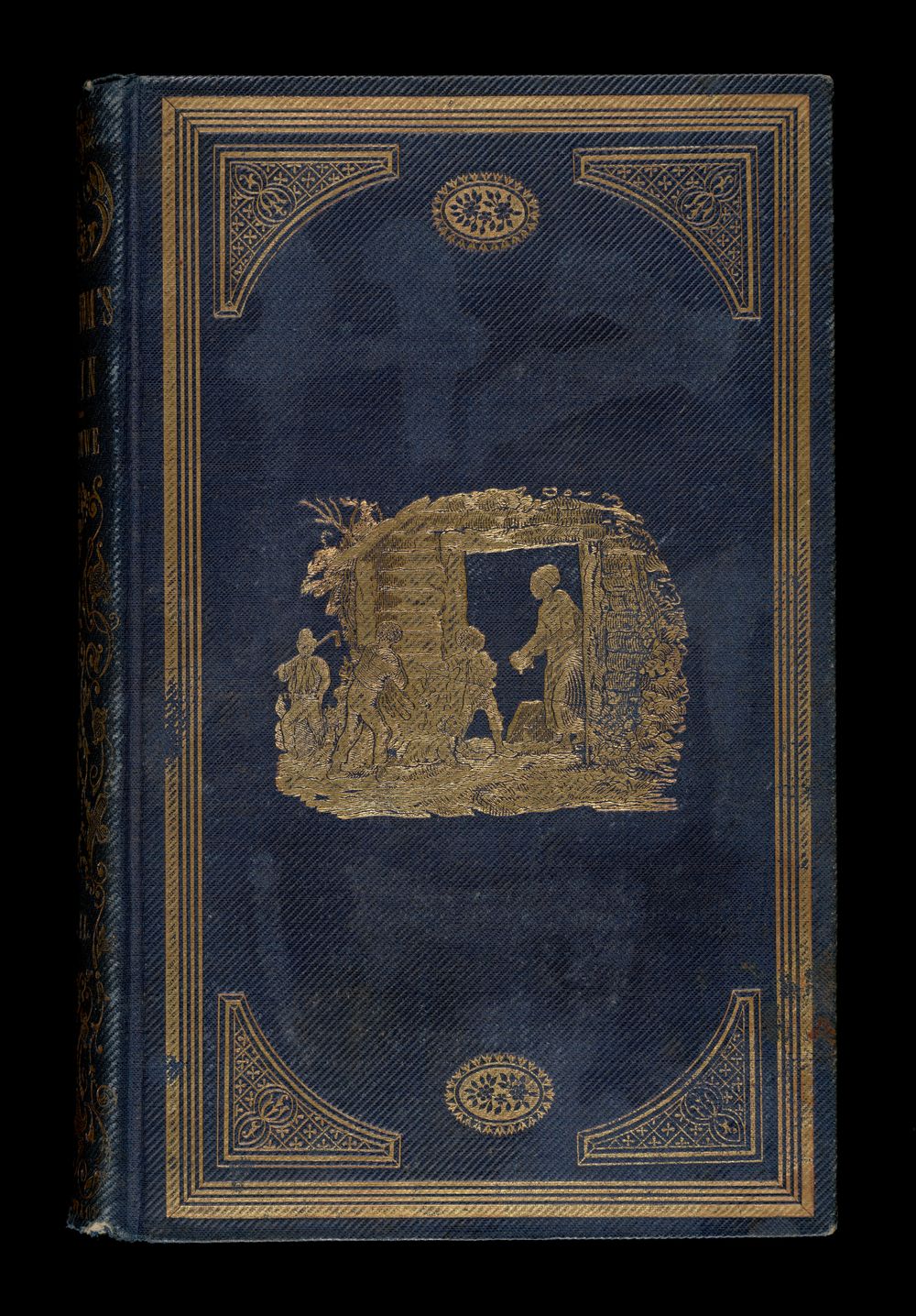

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896). Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly. 2 vols. Engravings by Hammatt Billings. Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1852. The Howard T. Behrman Collection.

First appearing weekly in The National Era from June 1851 to April 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin became the most talked-about book of the century and the most impactful work of all American literature. Stowe’s sympathetic yet stereotype-laden protest novel forced previously disengaged readers to see slavery’s cruel injustice, galvanized the Abolitionist movement, and framed the moral crisis that precipitated the Civil War. This first edition bears the publisher’s “gift binding.”

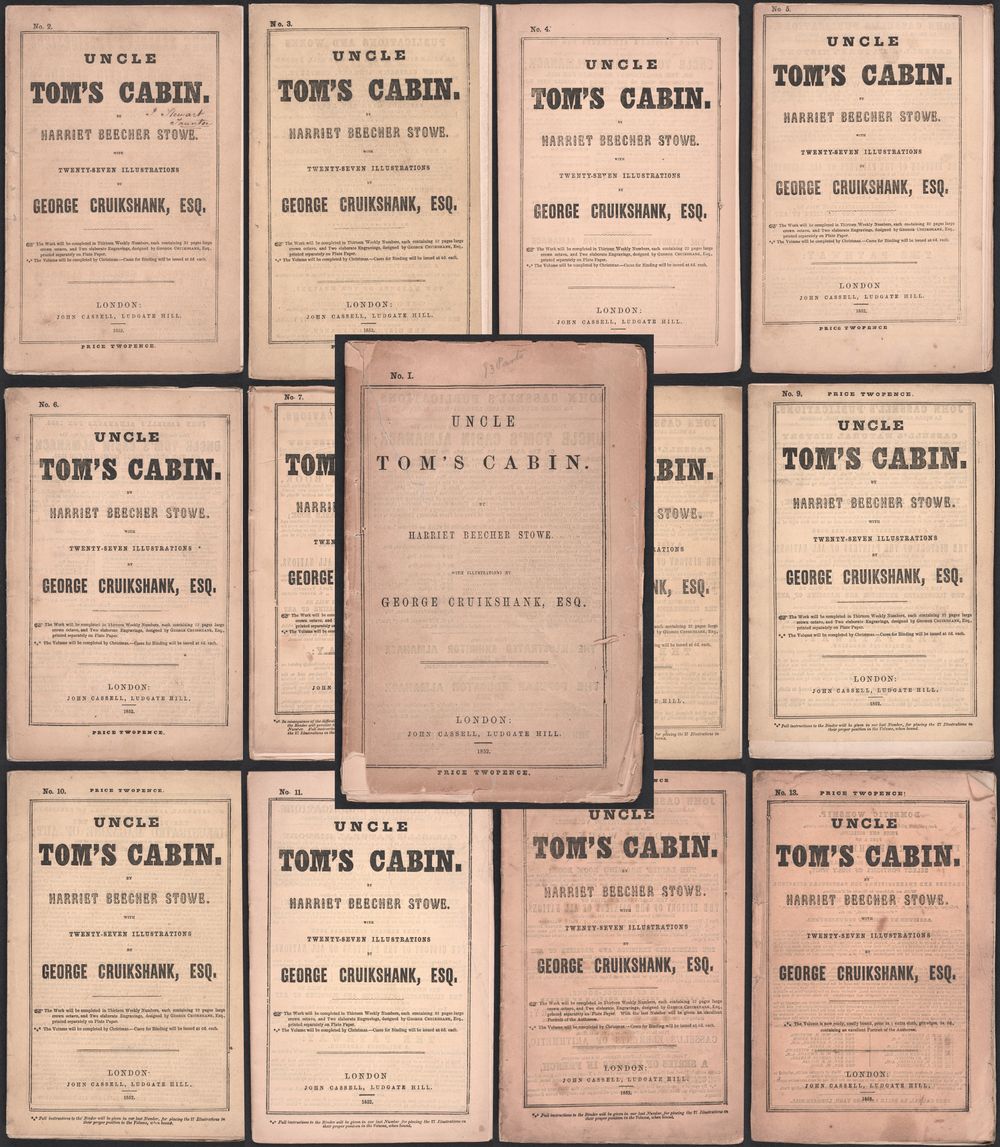

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896). Uncle Tom’s Cabin… with 27 illustrations on wood by George Cruikshank, Esq. London: John Cassell, 1852.

The subject of unprecedented publicity and national controversy, Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a publishing sensation. Some 3,000 copies of the two-volume first edition were sold in Boston on March 20, 1852, and sales reached 300,000 nationwide within the first year. Stowe’s novel also enjoyed immediate commercial success in England and appeared in numerous translations abroad. This illustrated London edition was issued in 13 weekly installments beginning on October 23, 1852.

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896). Autograph letter signed, addressed to “Dear Sir.” Hartford, Connecticut, 27 August 1886. Mr. and Mrs. William Cahn.

“I know of no story which told would exactly correspond to that of U[ncle] T[om]’s Cabin & yet there is no character there that I have not seen the exact counterpart of – no incident that I have not known of exactly the same kind. I have often said that the novel is a ‘mosaic of facts’ – some personally known to me during a near residence to the state of Kentucky.”

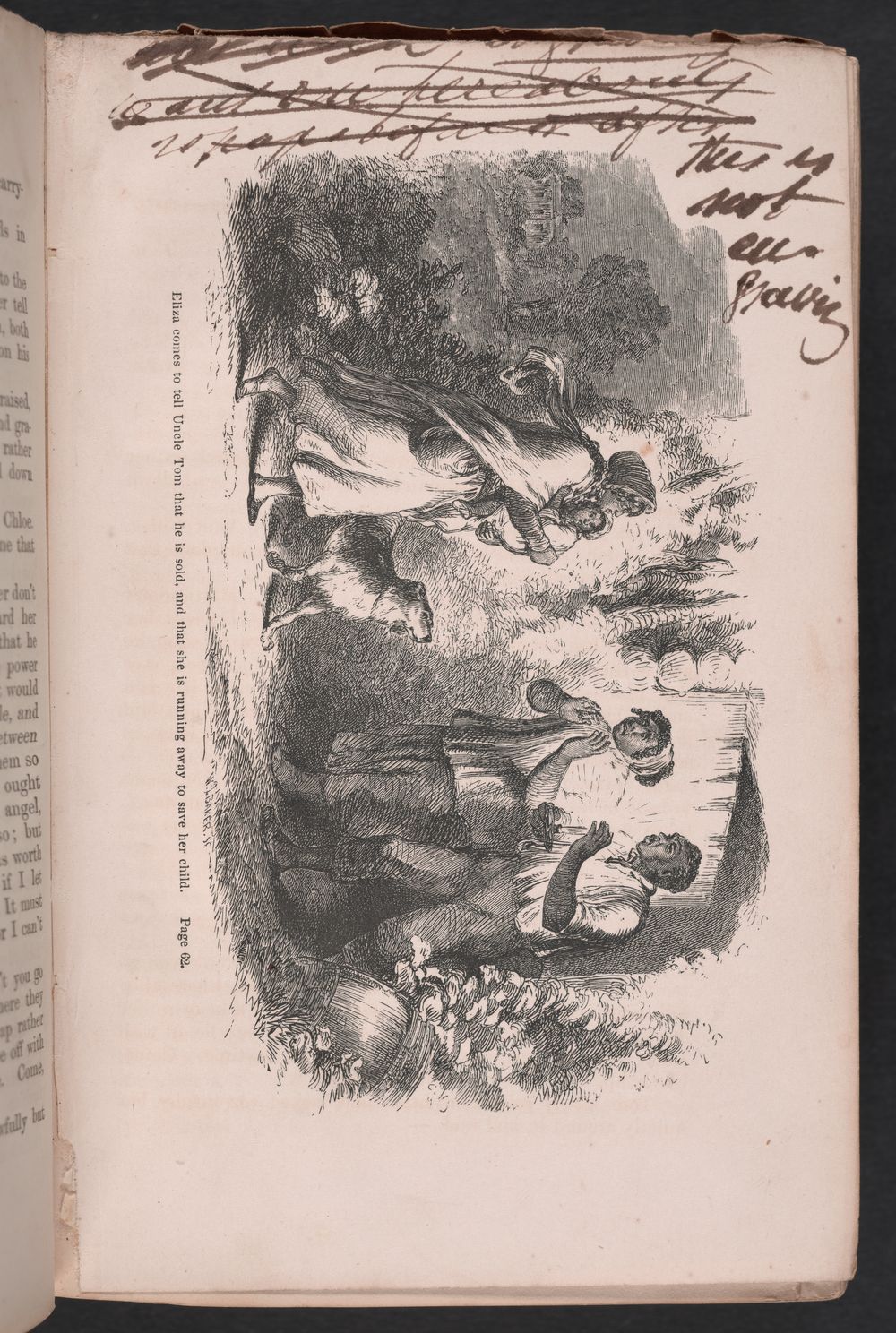

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896). Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Author’s Edition. London: Thomas Bosworth, 1852.

Harriet Beecher Stowe owned this copy of the 1852 “Author’s Edition” of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the only British edition that paid her royalties. She pasted four annotated slips and three cut-out plates from the first Boston edition into the volume to indicate where she wanted a selection of old and new illustrations (including a frontispiece of Eva reading the Bible to Uncle Tom) to occur within another proposed London edition.

Put these books upon some spare shelf for my sake – and let it be upon some shelf which has room for all I may write hereafter. Trust me, that though they should be a hundred volumes, I shall never once forget that row of yours.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870). The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. 20 parts in 19 vols. Illustrations by Robert Seymour (d. 1836), R. W. Buss, and Hablot K. Browne (“Phiz”). London: Chapman & Hall, April 1836 to November 1837. The Morris L. Parrish Collection.

Dickens’ publishers marketed his debut novel much as cheaper “popular” genres had been in the past: as inexpensive monthly parts issued with paper wrappers, illustrations, and advertisements. Although the first few parts sold poorly, Dickens’ gift for storytelling turned the enterprise into a breakout success that energized British consumption of novels throughout the Victorian era. This is one of 17 known “prime Pickwicks” consisting of first issues of each part.

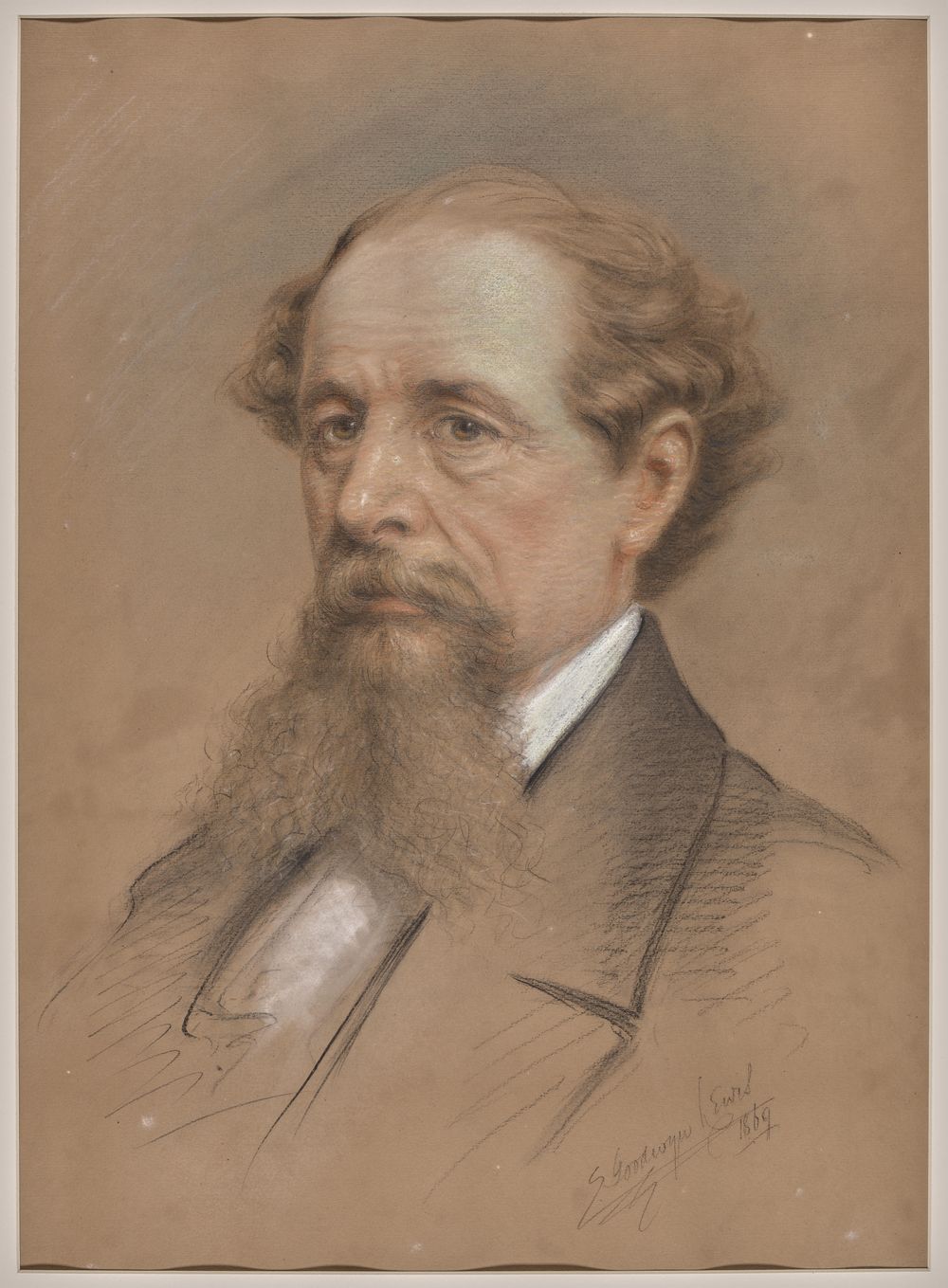

Edward Goodwyn Lewis (1827–1891). Portrait of Charles Dickens. Colored chalk drawing on paper. [London,] 1869. Thomas Woodward Hotchkiss, Class of 1889.

This striking portrait from the final year of Dickens’ life was the last for which he sat. Dickens presented it to his publisher Frederick Chapman (1823–1895), who, in 1859, had rekindled the novelist’s relationship with the publishing firm of Chapman & Hall, which had lapsed in the years following the success of the “Pickwick Papers.”

Frederick William Burton (1816–1900). Mary Anne Evans. Charcoal drawing on paper. London, “The Priory,” 14 February 1864. The Morris L. Parrish Collection.

Known worldwide by the pseudonym “George Eliot,” Mary Anne Evans wrote in her journal on February 14, 1864, that “Mr Burton dined with us and asked me to let him take my portrait.”This veristic sketch by Sir Frederick William Burton served as a preparatory study for his finished colored chalk portrait (with the novelist’s face turned more into shadow on her right) in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

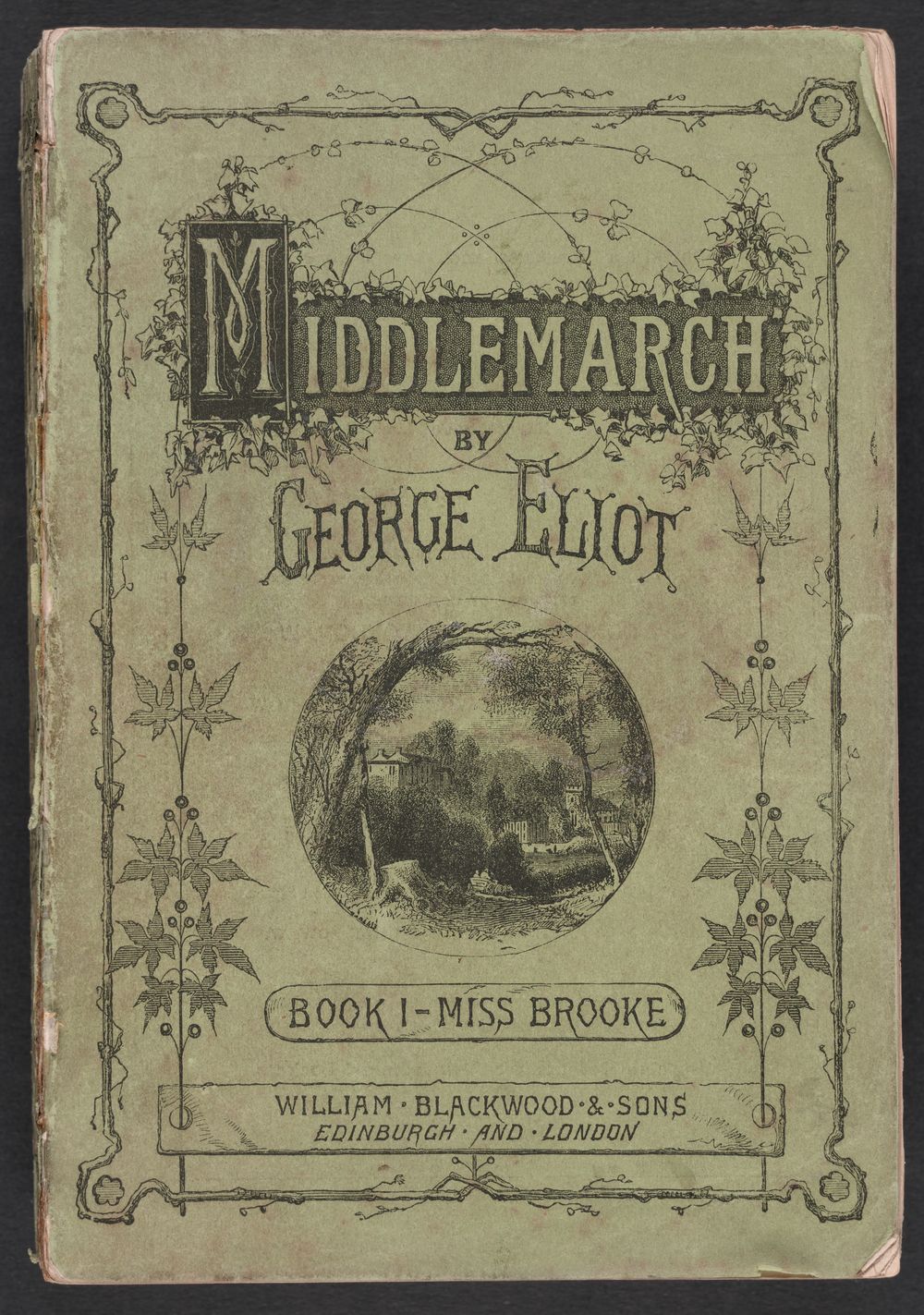

George Eliot (1819–1880). Middlemarch. A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871-1872. The Morris L. Parrish Collection.

George Eliot’s towering achievement, Middlemarch, was first published in eight audaciously lengthy installments, bimonthly from December 1871 to October 1872, and then monthly in November and December 1872. The eight parts of Princeton’s copy, preserved in remarkable condition within their original illustrated paper wrappers, each bear Eliot’s inscriptions “With the author’s compliments” and the ownership signatures of one of her closest friends, the philosopher and activist Sara Sophia Hennell (1812–1899).

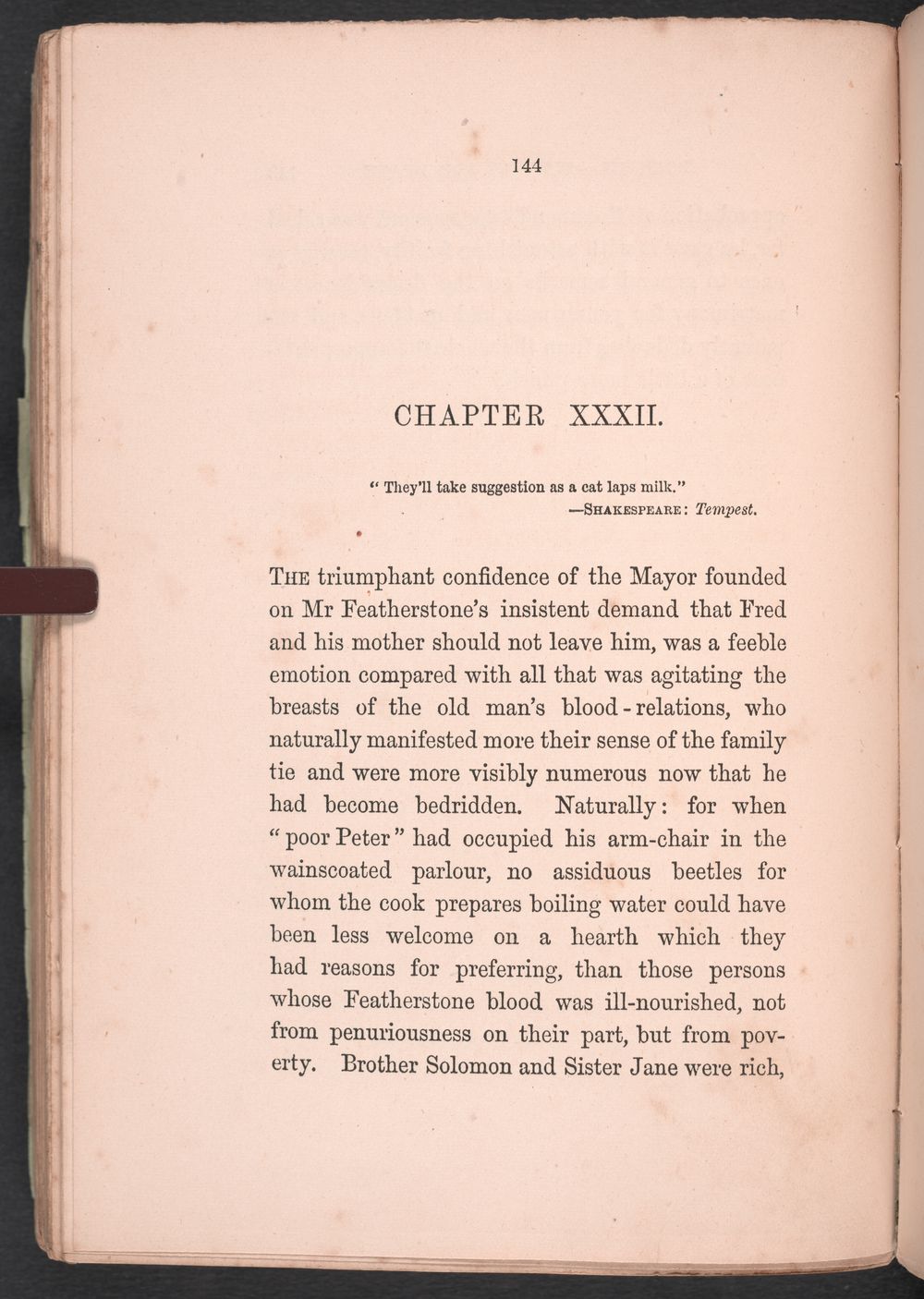

George Eliot (1819–1880). Middlemarch. A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871-1872. The Morris L. Parrish Collection.

In the third volume of Middlemarch, chapter 32 is preceded by an epigraph from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Act 2, Scene 1: “They’ll take suggestion as a cat laps milk.” Eliot had jotted this line down in her “Romula” notebook (Bodleian Library, MS Don.G.8) ca. 1864 and quoted it here in relation to the spectacle of greed that is witnessed when a rich man’s relatives gather around his deathbed.