GLOBAL ENGLISHES

Literatures in English: The Impact of Lingua Franca in Empire

During the height of the British Empire -- which spanned regions such as the South Pacific, Africa, North America, the Caribbean, as well as neighboring Ireland and Scotland -- over a quarter of the world's population fell under its dominion. Administering such a vast territorial Empire posed not only legislative and logistical challenges for the Crown but also cultural ones. British Imperial administrators embarked on a cultural project by exporting literature and the educational system to colonial outposts, aiming to reshape its colonized subjects in the image of the metropole. Many canonical works reflected the social, political, and cultural logics of Imperialism, and colonial education systems that sought to replace local knowledge with British aesthetics, norms, and reasoning through literary socialization. Imperial expansion faced opposition and conflict, ultimately leading to decolonization efforts and the eventual transition from Empire to Commonwealth. This produced a diverse range of post-colonial experiences, as depicted by various literary tropes, including the portrayal of insanity, fractured identity, and cultural alienation. This section examines literature created by former British colonial subjects during or shortly after decolonization. It explores how these authors discuss and repurpose the English language and its canonical tropes to capture their lived experiences within the Empire.

The Heinemann African Writers Series, established in 1962, played a pivotal role in shaping African literature and its global recognition. With its commitment to publishing works by African authors, the series has provided a platform for voices previously marginalized by the literary canon. By offering a diverse range of narratives, the series has expanded readers’ understanding of African cultures, histories, and social issues. Moreover, the publication of these works has empowered African writers to assert their identities and challenge prevailing narratives of Africa. The Heinemann African Writers Series has not only enriched the literary landscape but also contributed to the decolonization of knowledge and the promotion of cultural exchange. Its impact continues to resonate, influencing subsequent generations of writers and fostering a greater appreciation for African literature worldwide.

“I feel that the English language will be able to carry the weight of my African experience. But it will have to be a new English, still in full communion with its ancestral home but altered to suit its new African surroundings.”

Chinua Achebe (1930–2013). Things Fall Apart. London: Heinemann, 1958.

Drawing its title from William Yeats, “The Second Coming,” British Nigerian-born Achebe explores the cultural and political ramifications of colonialism. Okonwo, the protagonist, grapples with the influence of white missionaries on the traditional Igbo society. Achebe demonstrates the transformation of British English to local context; the dialogue incorporates Igbo words and phrases to construct a new form of African English that captures the coexistence of oral traditional practices and the persistence of colonial language and culture.

Chinua Achebe (1930–2013). Things Fall Apart. London: Heinemann, 1962.

Mass-market paperbacks demonstrate the broad circulation of African literature facilitated by the African Writers Series, for which Achebe served as its long-time editor. The transition to easy-to-print paperback editions gave global readers “something other than the traditional fare of English classics.” Heinemann was a powerful force in the development and promotion of literature from and about the continent. This copy is inscribed to civil rights activist, sociologist, and university professor Adelaide Cromwell Hill.

William Butler Yeats (1865–1939). “Second Coming” in Michael Robartes and the Dancer. Dundrum: The Cuala Press, 1920.

Published in 1919, amidst the turbulence of the Irish War of Independence, “Second Coming” captures the prevailing sense of uncertainty, produces a powerful illusion to the inevitable rise and fall of empires, and presents a bleak vision of a society on the brink of collapse. The poem’s ominous imagery and prophetic tone transcend its original historical context, making it one of the most celebrated and enigmatic poems of the 20th century.

Raja Rao (1908–2006). Kanthapura. New York: New Directions, 1963.

Originally published in 1938, Kanthapura explores the highly political events of the Indian Independence movement and the impact of colonialism on rural communities during their struggle for freedom. Inspired by the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi, the villagers unite to fight against British oppression and participate in the national movement for independence. Rao skillfully incorporates elements of Indian culture and the Kannada language, evoking oral folklore throughout the work.

V.S. Naipaul (1931–2018). A House for Mr. Biswas. London: Andre Deutsch, 1961.

Regarded as a prominent British literary figure, Trinidadian-born Naipaul’s reputation was accompanied by controversy. Naipaul’s grandfather was among the 1.6 million Indian indentured laborers transported to British colonies after the abolition of slavery. His protagonist, Biswas experiences displacement and isolation as he grapples with questions of identity and “homeland.” Naipaul, who permanently emigrated to England in his twenties, has controversially argued that the Caribbean, in lacking a language of its own, therefore also lacked a history.

V.S. Naipaul (1931 - 2018). Acceptance Speech for Bennett Award. Typescript manuscript draft, 1980.

Naipaul was awarded the Bennett Award in 1980. In his speech, Naipaul reflected on the reception and criticism of his work and the practice of writing as a vocation. He goes on to state that he “was born in a small island where the book–as the new, created thing–doesn’t exist.” Naipaul has been much criticized for his depiction of developing countries in his novels and, in particular, for his dismissal of Caribbean intellectualism and historicity.

Bessie Head (1937-1986). A Question of Power. London: Davis-Poynter, 1973.

As one of South Africa’s most influential women writers, Head draws frequent comparisons to Toni Morrison. In her third novel, Head skillfully employs a non-linear epistolary format, crafting an allegorical journey through South African history. The protagonist, Elizabeth, experiences episodes of madness, a manifestation of the trauma of being “coloured” during Apartheid. Despite her acclaim, Head’s longtime publisher rejected the manuscript, citing her “misuse of the English language.”

Currer Bell (pseud. Charlotte Brontë). Jane Eyre. An Autobiography. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1848. Morris L. Parrish Collection.

To explore the societal constraints placed upon women, Brontë draws a striking parallel between the two central female characters, who serve as mirror images of one another. Whereas Jane, the protagonist, is portrayed as strong-willed and independent, we are meant to understand that Bertha’s madness is brought on by years of denied agency as indicated by her confinement and the suppression of her Creole identity.

Jean Rhys (1890 - 1979). Wide Sargasso Sea. London: Andre Deutsch, 1966.

After reading Brontë, Rhys wanted to humanize the madwoman in the attic– to “try to write her a life.” She reimagines Antoinette “Bertha” Rochester and the conditions leading up to her forced confinement and madness. Born to white Creole plantation owners in Jamaica after the abolition of slavery, Antoinette is married off as a means to preserve wealth and property. Sent to England, she is driven mad by the conjoined forces of spousal alienation, colonialism, and patriarchy.

James Ngugi (né Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o) (1938– ). Weep Not, Child. London: William Heinemann, 1964.

The first novel in English to be published by an East African writer, Weep Not is set on the eve of the Mau Mau uprising. The autobiographical work explores the complex dynamics between white settlers and Africans in colonial Kenya, particularly the impact of English language education, and its promises of social mobility and economic uplift. This copy is inscribed with the novel's opening line: “Nyokabi called him. She was a small, black woman, with a bold but grave face.”

Derek Walcott (1930 - 2017). Dream on Monkey Mountain and Other Plays. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1970.

Set on the island of St. Lucia, while it was still a part of the British Empire, Walcott’s play dramatizes the relationship between Europe and Africa, for which the Caribbean serves as both a thematic and political intermediary. Walcott explores the self-alienating experience of racism, and its capacity to cultivate madness. Alluding to Plato’s allegory of the cave, the protagonist experiences profound despair as he navigates a colonial ideology that teaches Britain’s black subjects to valorize whiteness and devalue blackness. In 1971, the Negro Ensemble Company off-Broadway produced Dream on Monkey Mountain in New York, winning it an Obie Award. Walcott would earn a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992, becoming the second Caribbean writer to do so.

George Lamming (1927–2022). In the Castle of My Skin. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1953.

Lamming explores the cultural consciousness of a Caribbean island village during the politically and socially turbulent 1930s and 1940s. As the Great Depression begins to have a destabilizing impact on British imperial colonies, Lamming explores themes of outmigration and immigration. A significant political work in colonial literature, Lamming adeptly foreshadows the fraught transition from colony to commonwealth prior to independence. The introduction is written by Richard Wright, with whom Lamming developed a friendship during the late 1940s.

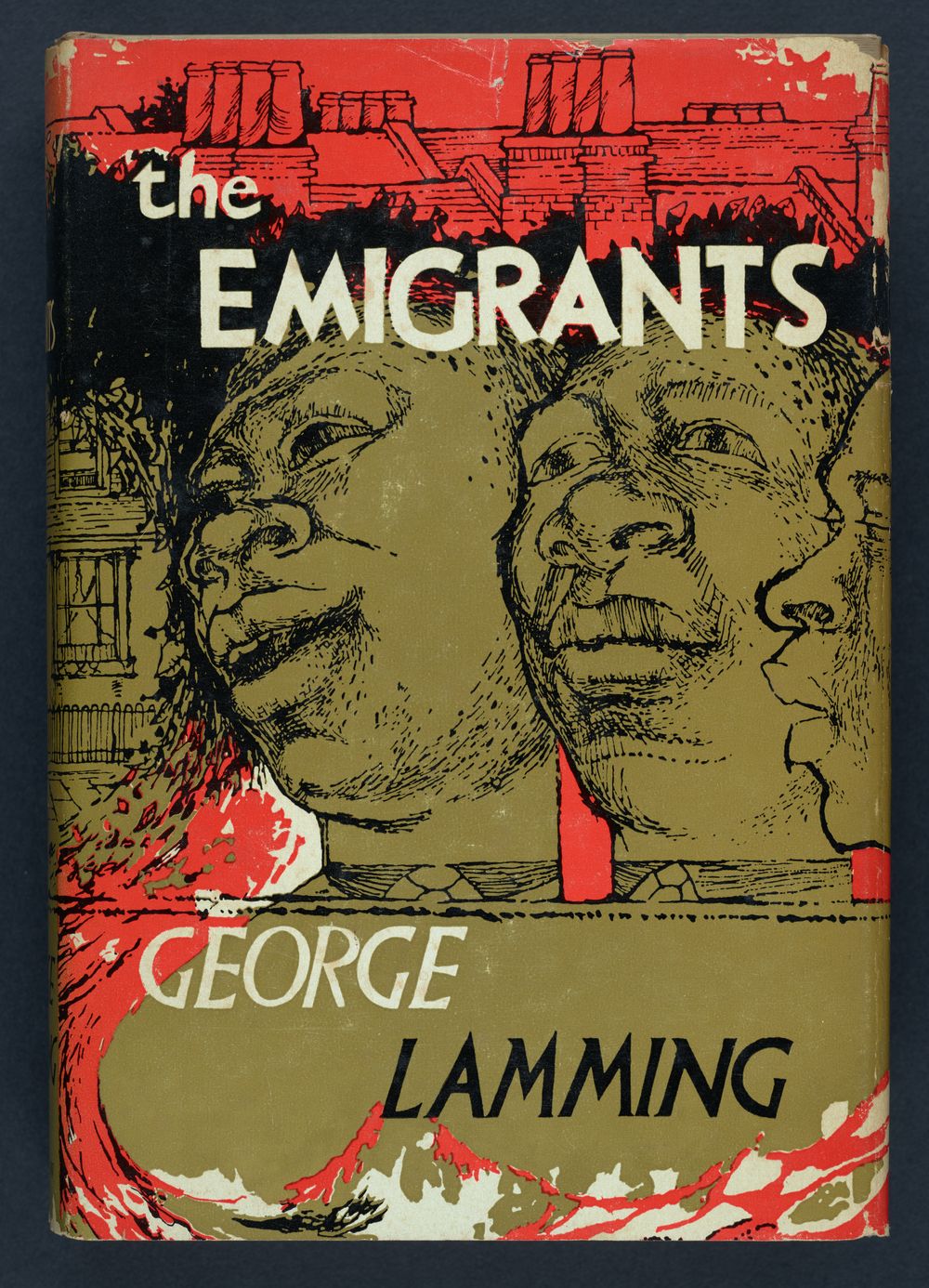

George Lamming (1927–2022). Ralph Ellison’s Advance Reading Copy of The Emigrants. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1954.

In his second novel, Lamming explores the shifting climate in London, as British colonies transition toward commonwealth status. The plot centers around the experience of emigrating by boat from the colonized periphery (Caribbean) to the center of the British Empire. In narrating a physical voyage across the Atlantic, Lamming orchestrates for his reader a second transatlantic journey, whereby Black subjects are now citizens rather than cargo. He tackles the fraught experience of longing for British approval.

Typescript letter to Ralph Ellison introducing The Emigrants by George Lamming, 1955.

This advanced review copy was sent to Ralph Ellison, sent by Lamming’s publisher, McGraw-Hill, seeking a favorable review for his second book. The letter elucidates the publishing and marketing infrastructure that connects Black male authors at the time. Levinthal, in describing the novel’s plot as being “concerned with the isolation of man and the human predicament” echoes some of the language and themes in Ellison’s Invisible Man.

Carlos Bulosan (1913–1956). Letter from America. Illinois: The Press of J. A. Decker, 1942.

Bulosan, who immigrated to the United States in 1932 as a laborer, would soon become one of the most prominent Filipino-American writers of his generation. While living in Los Angeles, Bulosan became involved with leftist political organizing, during which he met Louis Adamic, to whom this copy of Letters from America is inscribed. Adamic was himself a leftist public intellectual and immigrant activist.

Carlos Bulosan (1913–1956). The Laughter of My Father. London: Michael Joseph Ltd, 1945.

Bulosan’s memoir sheds light on peasant resistance against the neo-colonial system governing class and mobility in the Philippines on the eve of World War II. Bulosan employs humor to underscore the intersecting local and global class dynamics experienced by Filipino migrants, as well as their resilience. The book offers a poignant depiction of the consequences of colonialism on Filipino lives.

Michelle Cliff (1949–2016). From Abeng: a description of Nanny the leader of the Windward Maroons. Broadside. Indiana: Helaine Victoria Press, 1984.

Cliff’s debut novel was a subversive history of Jamaica. Using intricate historical flashbacks and contemporary vignettes, the work constructed an alternative narrative that amplified the voices of historically marginalized and silenced communities on the island, offering a nuanced portrayal of their experiences. The title is a direct reference to the musical instrument used by the Akan people of Ghana, which was a communication tool used by Maroons to free themselves from enslavement.

Jamaica Kincaid (1949– ). Handwritten greeting card to Betty Guyer, 1990.

Kincaid thanks her friend Elizabeth Guyer, an assistant editor at the New Yorker, for her support and encouragement of her third novel, Lucy. While a staff writer for the New Yorker, Kincaid published experimental non-linear stream-of-consciousness pieces, reminiscent of Joyce and Woolf. Kincaid remarks on the evolution of Lucy, saying, “By now you can see Lucy is in a book. You have always been so kind to me with your words of support and I appreciate it greatly.”

Jamaica Kincaid (1949– ). Uncorrected Proof of Lucy. London: Jonathan Cape, 1990.

Lucy is praised for its innovative use of intertextuality, integrating canonical works including Paradise Lost and Jane Eyre. As a child, Lucy must memorize Wordsworth but experiences profound alienation in doing so. She cannot reconcile the universality of the “beauty of the daffodils,” with her Caribbean landscape where they simply will not grow. Subsequently, her first encounter with daffodils produced not bliss but anger, a commentary on an education system that privileges knowledge that neither reflects the experience nor the landscape of British colonial citizens.