This digital archive, “The Guatemala Atrocity Trials,” documents the ground-breaking atrocity trials that occurred in Guatemala’s domestic courts after that country’s thirty-six-year armed conflict (1960-1996). The court records in this archive were collected by Temple Law Professor Rachel López, formerly a fellow of Princeton’s Program in Law and Public Policy, curated by Princeton Librarian David Hollander, and summarized by Guatemalan human rights attorney Astrid Escobedo.

Background

Guatemala is the site of a remarkable sequence of historic firsts in the realm of transitional justice. In 2013, Guatemala’s former dictator, Efraín Ríos Montt, was convicted of genocide for his role in the massacre of Ixil villages in 1982. This was a landmark moment, not just for Guatemala, but for the world. Although his conviction was later overturned on shaky procedural grounds and he died before his re-trial concluded, his case is still historic as it represents the first time that a former head of state was indicted and convicted of genocide in their own country. Then, in 2016, due in no small part to the activism of a group of Mayan women who were held as sexual slaves at the Sepur Zarco military base during the armed conflict, Guatemala’s High Risk Tribunal A—a special court set up to try sensitive cases—became the first national court in the world to prosecute sexual violence as a crime against humanity. That same year, fourteen military officers were charged in the largest case involving enforced disappearance in Latin America, after exhumations unearthed 558 human remains from mass graves at a former military base. These high-profile cases are just the tip of the iceberg. While the common perception of Guatemalan transitional justice is that prosecutions for grave human rights violations are a relatively recent advent, through the field research in Guatemala, López was able to document numerous cases that pre-date these notable cases.

The Collection

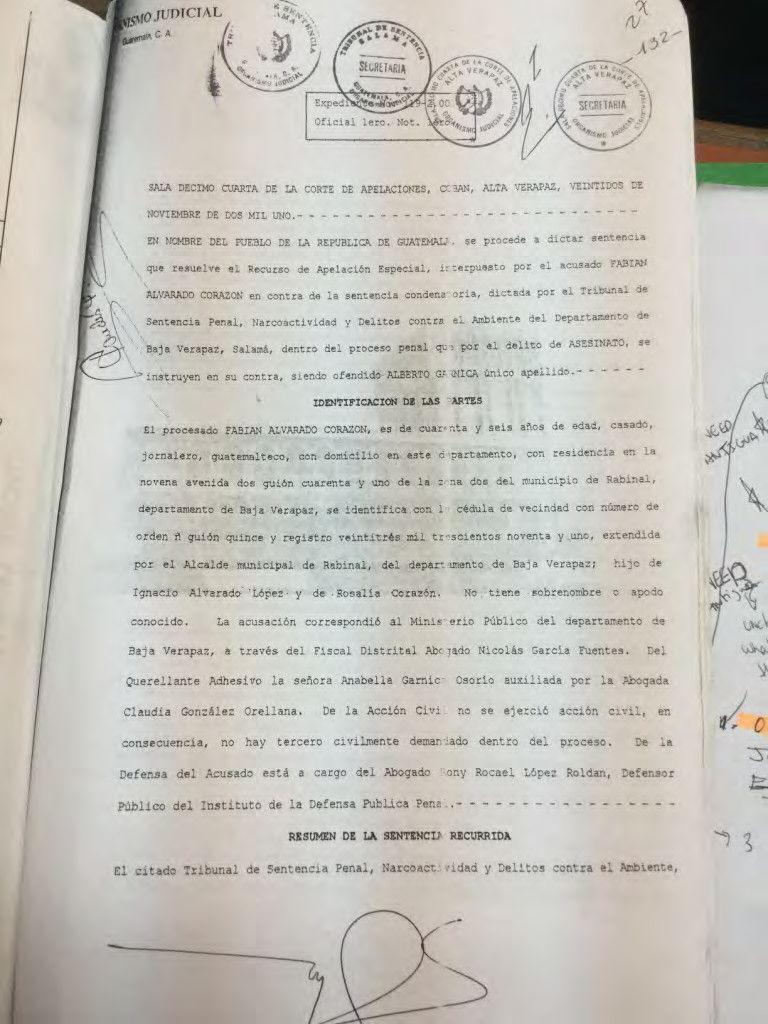

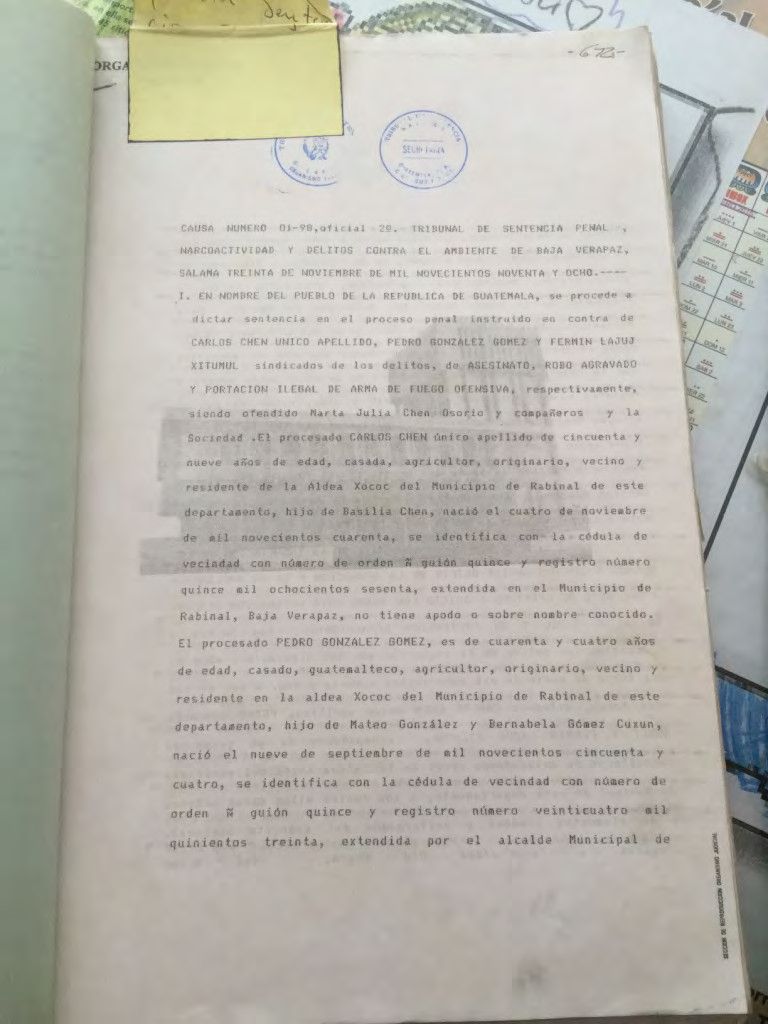

This archive documents these cases. In total, López identified thirty-two cases involving atrocities committed during the armed conflict that resulted in convictions starting from 1993 to the current day. This archive includes court records of the conviction and sentencing decisions in twenty-four of the cases, which López obtained from multiple sources, including the human rights lawyers and prosecutors who litigated them, the judges who oversaw them, or the judicial archives in municipalities across Guatemala. Under Guatemalan law, these judgments are technically public, but because of the extraordinary difficulty of obtaining them, this project was the first to pull them together into one collection.

Related Research

These court records tell the story of the evolution of transitional justice in Guatemala. Early on, Guatemalan courts exclusively depicted even the gravest international crimes as common crimes like homicide, assassination, or kidnapping committed by rogue actors. Over the last decade, however, Guatemala prosecutors and judges trained their focus on those who orchestrated the commission of grave crimes, but relied on their subordinates to carry them out, charging the orchestrators with international crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, and enforced disappearance. Additionally, as analyzed by López in Post-Conflict Pluralism, although Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) have often been portrayed as second-rate substitutes for criminal prosecutions, these court records illustrate how the investigations and reports of TRCs in Guatemala facilitated criminal prosecutions there. As these court records demonstrate, when the state apparatus is compromised due to its involvement in the underlying atrocities, TRCs can act as essential investigators and custodians of evidence.

But these cases are not just relics of the past.In The Paradox of Punishing for a Democratic Future (University of Illinois Law Review, forthcoming), López and political scientist Geoff Dancy demonstrate how these cases continue to impact democratic institutions and behaviors in Guatemala today, both increasing political engagement, but also risking backlash. These findings are likely more generalizable. Indeed, drawing from the Guatemalan case study, López and Dancy developed a set of hypotheses about the possible democratic effects of punishing state officials for their crimes and tested them using the Transitional Justice Evaluation Tools (TJET), the most extensive global data set of human rights prosecutions. The resultant findings reveal a paradox. While criminal prosecutions of state officials for human rights violations are associated with some pro-democracy outcomes, like increased civil society activism and pro-democratic mobilization, they are also associated with greater political polarization and anti-system backlash.

We hope that this collection will be an important resource not only to researchers, but also to the Guatemalan people, providing access to historical documents that otherwise would remain hidden away from public view, and if not preserved, gradually vanishing.