Upheaval and Indigenous Resistance in Dongalo

By Jan Cherome Sison, Joaquin Manuel Gopez Reyes, Carlos Joaquin R. Tabalon, Nicholas Sy, and Christina H. Lee.

The case presented here took place at the end of May of 1717. It involved the resistance of some of the indigenous principales in Dongalo to the authority of the Augustinian priest, Juan Serrano, who was put in charge of the evangelization of the pueblo. The disagreement between the two parties was about the placement of the dividing line that indicated the section of the land that was to be ruled by the indigenous colonial officials in Dongalo and the section that was under the jurisdiction of the Augustinian order. The confrontation ended up in a physical altercation between the priest and his indigenous opponents. Although there were no severe injuries—only some minor wounds—that resulted from the quarrel, Fray Serrano viewed the altercation as evidence of contempt from the respective indigenous members of Dongalo towards their assigned spiritual leader.

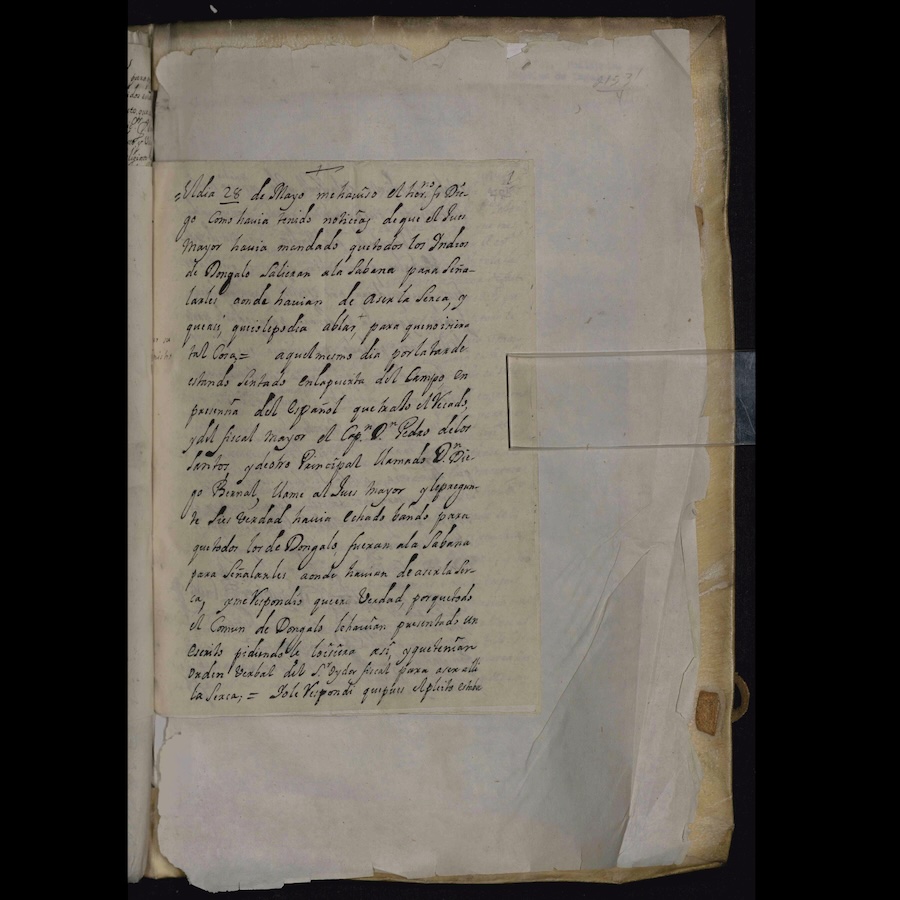

According to the testimony of Fray Serrano, the juez mayor of Dongalo—an indigenous principal—had ordered the members of the community to build a fence on Monday, 31 May 1717, demarcating the land that was in their possession.[1] According to the local judge and his fellow indigenous officials, it was the Dongalo natives themselves who requested that the fence be built. The juez mayor claimed that he had received the verbal judgment from the oidor fiscal in the favor of the principales, but Fray Serrano believed that the case was pending judgment in the court of law in Manila and demanded that all action regarding the building of the fence be put to a stop.

The juez mayor disregarded Fray Serrano’s demand for a written mandate from the oidor fiscal and ordered about three hundred residents of Dongalo of all ages to build the fence on the indicated Monday. Attempting to put a stop to the project, Fray Serrano along with his principales attendants and servants, appeared at the site of the construction of the fence, in an area known as Santa Lucía. Fray Serrano admonished the local judge and his chief counsel, Captain Pablo, for disobeying his orders to which the latter is purported to have responded, “I know very well what I do, and I know which are our lands and you don’t. We are making this fence because we know that up to this point, we have our lands and you do not know where yours are. And you are trying to take away what is ours” (img. 12). This was followed by an exchange of insults and accusations between the two parties.

Chaos ensued when Fray Serrano hit Captain Pablo with a stalk. Fray Serrano and his servant received some minor wounds after being hit by the natives but were able to flee to Manila to seek medical assistance. Fray Serrano produced the testimony at hand in the aftermath of the event. Two of his principales attendants served as witnesses of his testimony.

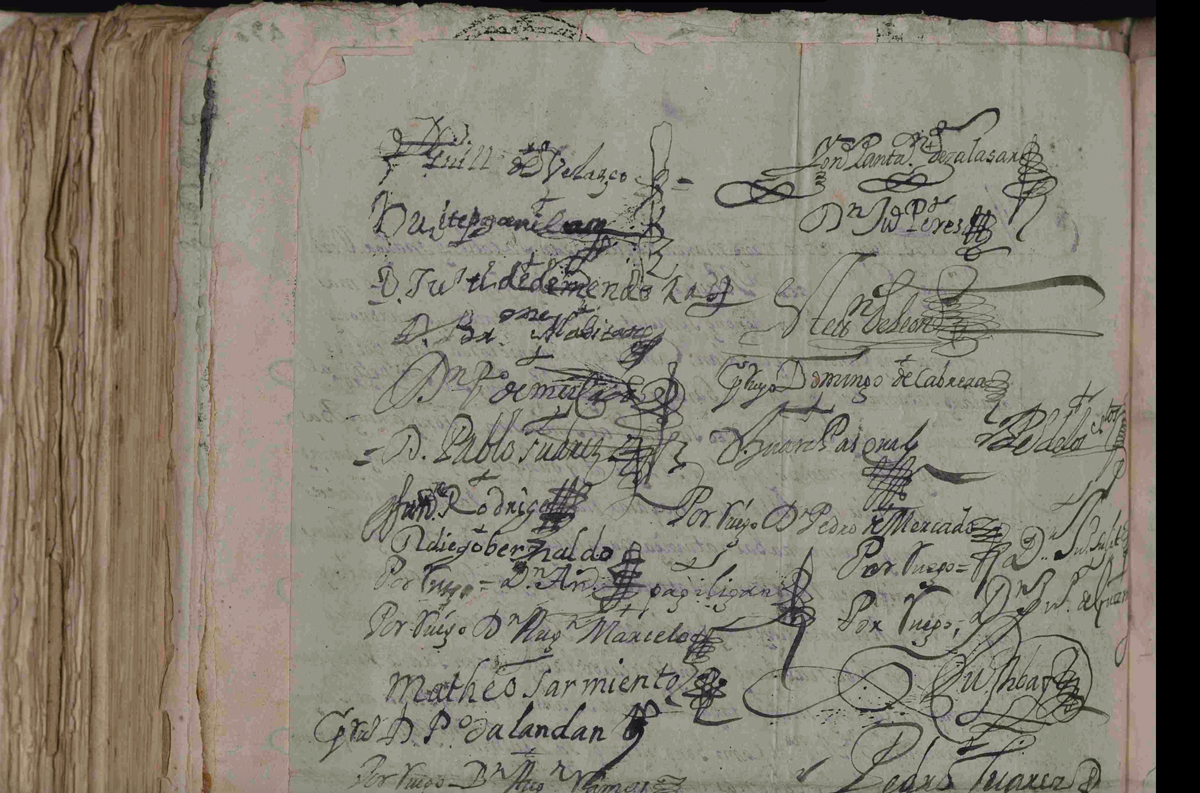

The first document of the report is a declaration produced by the principales of the visitas of Parañaque or Palanyag,[2] Las Piñas, and San Nicolás who signed a document to deny an accusation of Fray Serrano that they were involved in the upheaval in Dongalo, as well as to show their allegiance to the Augustinians. It is possible that upon learning of the event in Dongalo the Augustinian provincial went to Parañaque, the parish to which Dongalo belonged, and admonished its parishioners.[3] The purpose of this declaration was to ensure that the signatories did not suffer any form of penalty for the actions taken against the Augustinian minister of Dongalo. Let us recall that Don Juan Mamonong, among other signatories, wanted to distinguish themselves from those who asked the archbishop [Francisco de la Cuesta] to assign another cleric to Parañaque.[4] In the context of diocesan interventions into parishes run by religious orders, this declaration may have also freed the Augustinians from increased scrutiny into their management, or mismanagement, of the parish.[5]

Following the Dongalo tumult in 1717, the Augustinians continued to administer Parañaque, though it appears from the absence of Fray Serrano’s name in Sacramental registers, that Fray Serrano was relieved of its ministry. The name of Juan Serrano reappears from 1723-1725 in the Parañaque church records, where he is called by the title of prior.[6]

The Term "Indio"

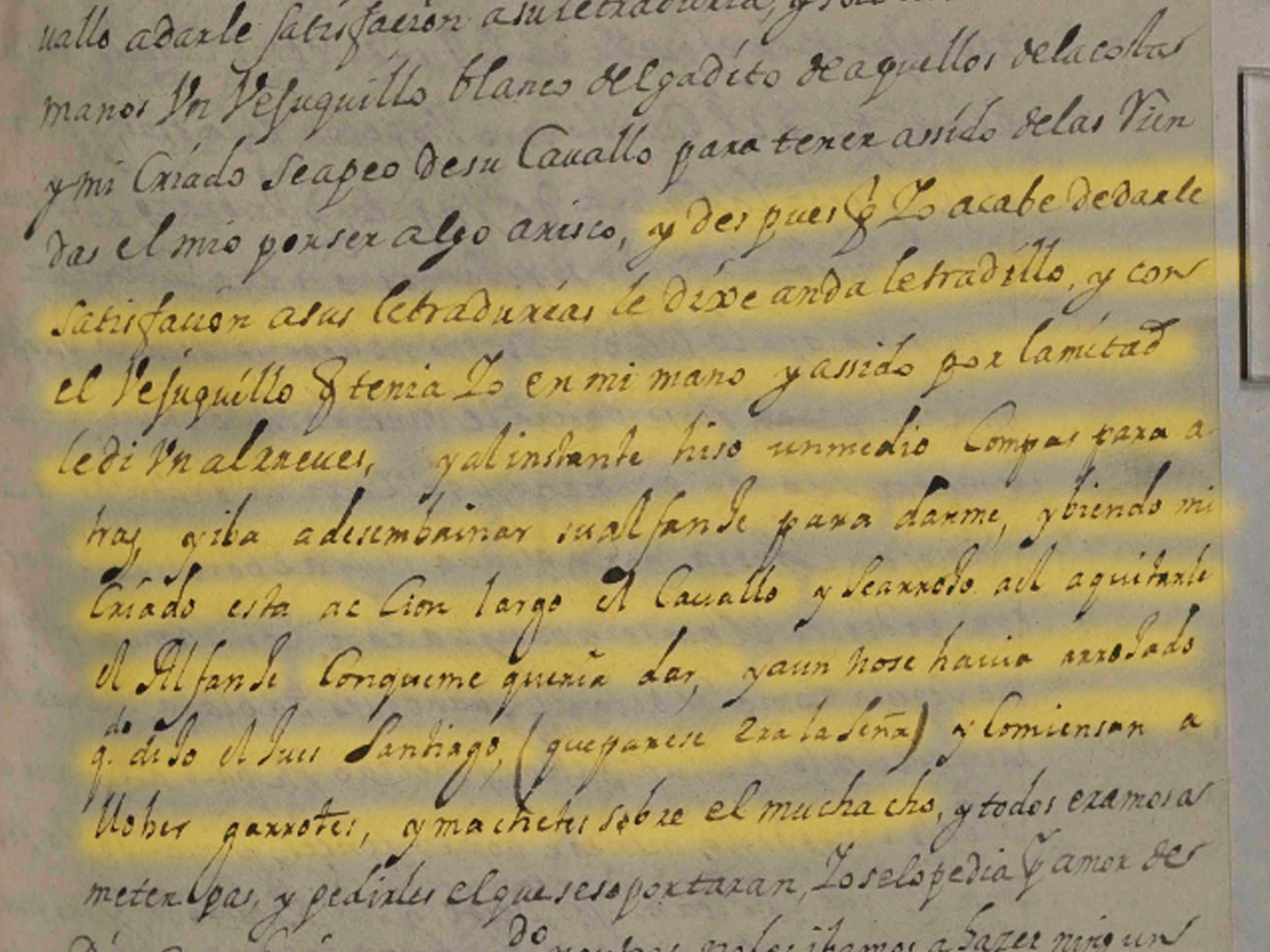

The term “Indio” was used in the Spanish-speaking world to denote any indigenous or native person from the “Indias,” whether they be in the Atlantic or the Pacific. In the Philippines, it was an umbrella term for Christianized natives in the archipelago. Although the natives of Dongalo were not regarded too highly in the document, the term Indio was not necessarily pejorative. In Fray Serrano’s testimony, we find two types of Indios. The first are the Indios who, despite having been baptized into the Catholic faith and having accepted Spanish rule, displayed disobedience to their minister. The Indio characters who exemplified this “wrong” and “unruly” conduct are the juez mayor, the local escribano, and all the other natives who took part in the Dongalo upheaval. It is telling that Fray Serrano refers to Captain Pablo by his name and title, but while narrating his altercation with his servant he calls him Indio in the derogative sense. He recalls that his servant was trying to take Captain Pablo’s scimitar, “he got a cut on the side of his hand with his own scimitar, because the Indio [that is, Captain Pablo] was resisting with force” (img. 14).

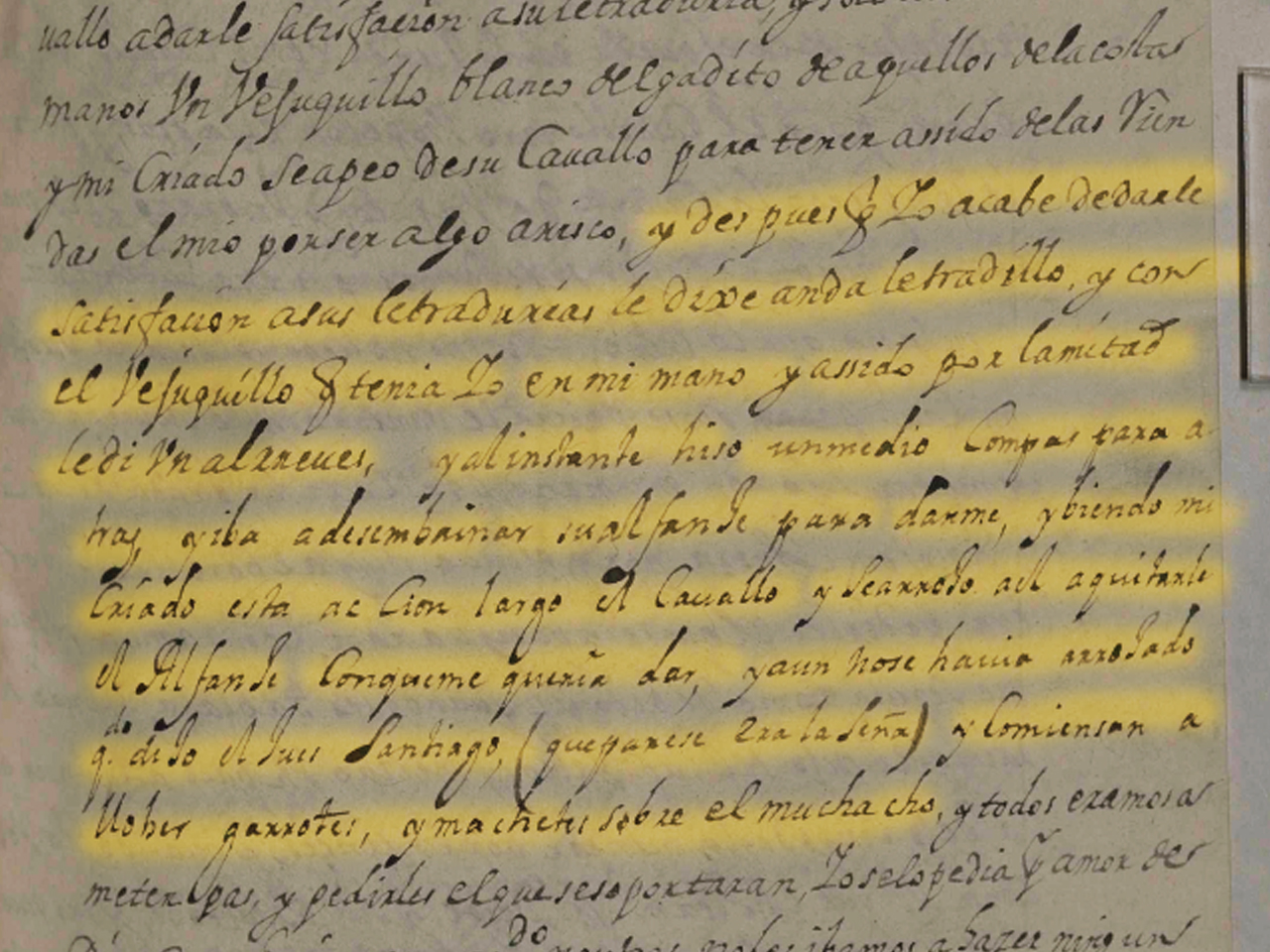

On the other hand, there are also Indios who could be distinguished because they obeyed and gave “due” deference to their minister, as a sign of their indebtedness (utang na loob) for having evangelized them. For example, Fray Serrano describes the “well-meaning Indios” (img. 15) who helped him recover from his confrontation with Captain Pablo. The Indio characters who exemplified this “right” conduct and have thus found favor with the Augustinian friars include the Indios who helped Serrano escape, Serrano’s servant who risked his life and well-being to defend him, the principales Don Ignacio Pantaleon, and Don Nicolas de Carabeo who signed as witnesses to Serrano’s testimony of the tumult, as well as the principales of Parañaque, Las Piñas, and San Nicolás who crafted the apologia addressed to the Augustinian provincial.[7]

Significance of the Document

While this is a document written from a Spanish point of view, it also exposes the voice of the natives who were then called Indios (see section above). This can be used in different areas as well such as social history because it speaks of people who are usually left unheard in traditional histories. More specifically, this document is important because it shows an episode of conflict between a member of the clergy and an official of the colonial bureaucracy; particularly, native officials. On the one hand, it can explain how friars did not question their entitlement to the land that they possessed. On the other, it illustrates the capability of the natives to resist dispossession when their interests were at stake.

It is worth reflecting on the fact that even in Parañaque, one of the most Christianized parts of the country, there was discontent among the natives. In the case of Dongalo, there were natives who did not completely accept the Spanish justification for the acquisition of native land. One wonders whether the actions of Captain Pablo were more motivated by a rejection of the religion of the foreigners, or of the foreigners themselves. Captain Pablo may have sought to free the people of Dongalo from the Augustinians –whether to liberate them from the demands of the friars or to gain greater control over them himself. Overall, the document sheds light on the social and political clashes between the natives and the Spanish missionaries, helping us—in the broader sense—to understand attempts to undermine foreign rule. The case could be added to the many native, often agrarian, uprisings which occurred during the Spanish colonial period of the Philippines.

Without predetermining a future that had not yet happened, the events in Dongalo presaged the Tagalog revolts of 1745. Roughly three decades after the Dongalo upheaval, principales and peasants from Parañaque joined different Tagalog towns in a revolt against monastic usurpation of land.[8] Into the next century, dispossession motivated continued grassroots resentments: roving bands of tulisanes (bandits) harassed friar estates in Tagalog areas,[9] and inquilino (tenant) disputes with these estates were central to the anti-clerical tone of the nationalism developed by ilustrados like Jose Rizal. [10]

Dongalo Today

In the present moment, Dongalo, officially “Don Galo,” is a barangay in Parañaque.[11] At the time when this report was filed, Dongalo was defined as a pueblo or town. Dongalo is located north of Parañaque River and sits by the Manila Bay. It is popularly believed that the name of the town was changed from Santa Monica to Don Galo in the late sixteenth century as recognition to a certain “Don Galo” who prevented the Chinese corsair Limahong from attacking Manila. This is possibly a spurious narrative, as none of the historical accounts from the sixteenth century mention the episode. Gaspar de San Agustin in his Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1698) highlights Limanhong’s attempt to attack Manila and his brief occupation of Dongalo. In San Agustin’s account of the episode (Chapter XVIII), he mentions that Parañaque was next to the River Dongalo, which led us to think that the town was named after the said river. There is no mention of the town carrying any other name at the time of Limahong’s occupation than Dongalo (not Don Galo).[12]

Relación y otros instrumentos sobre el desacato que los Naturales de Dongalo

Report and other documents on the contempt that the Natives of Dongalo, town of Parañaque, executed against their Prior and Minister (English translation of the title).

Notes

The conquered towns of Luzón and the Visayas were locally administered by the gobernadorcillo, the cabezas de barangays, a teniente mayor, and the jueces mayores. These roles were generally given to the members of the principalia or what was known as the común de principales (see Luis Ángel Sánchez Gómez, “Las élites nativas y la construcción colonial de Filipinas (1565-1789),” ed. L. Cabrero, España y el Pacífico, Vol.2 (Madrid: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, 2004), 7-70.

Parañaque and Palanyag were used interchangeably during this period. In this document, Palanyag is favored by the indigenous whereas Parañaque is used by the Spanish missionaries.

It was in 1575 when the Augustinians, led by Fray Juan de Orta, established the parish of Parañaque, with Saint Andrew as its patron. Dongalo was subjected under the parochial administration of Parañaque, being constantly grouped together in accounts such as in Gomez Perez Dasmariñas, “Account of the Encomiendas in the Philipinas Islands,” in The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, ed. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, vol. VIII, 55 vols., 1903, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/13742/pg13742-images.html#d0e912 and in Volumes I, II, III, XIV, and XXII of Isacio Rodriguez Rodriguez and Jesus Alvarez Fernandez, Historia de La Provincia Agustiniana Del Santísimo Nombre de Jesus de Filipinas, 22 vols. (Manila and Valladolid, 1994). For more detailed information on the ministry of Augustinians throughout the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines, see Elviro Jorde Perez, Catálogo Bio-Bibliográfico de Los Religiosos Agustinos de La Provincia Del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús de Las Islas Filipinas Desde Su Fundación Hasta Nuestros Días(Manila: Establicimiento tipografico del Colegio de Sto. Tomas, 1901),https://ustdigitallibrary.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/section5/id/95274.

"Francisco de La Cuesta | Real Academia de la Historia." Real Academia de la Historia, https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/54678/francisco-de-la-cuesta. Accessed 22 May 2023; Acta Apostolicae Sedis, XCV, no. 4 (2003)". Acta Apostolicae Sedis. April 5, 2003.

Damon L. Woods, "Out of the silence, the men of Naujan speak Tagalog texts from the seventeenth century," Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 63, no. 3 (2015): 303-340.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS). Bautismos 1682-1763. Church records (Paranaque), Film. Online database, https://www.familysearch.org, accessed 2023.

If they were viewed favorably, however, one wonders why even they felt implicated in the above events. Serrano does not incriminate them in his testimony.

Fernando Palanco, “The Tagalog Revolts of 1745 According to Spanish Primary Sources,” Philippine Studies 58, no. 1/2 (2010): 45–77.

Isagani R. Medina, “La Madre de Los Ladrones: Tulisanismo in Cavite in the Nineteenth Century,” Philippine Social Sciences Review 48, no. 1–4 (1984), 239, 245, https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/pssr/article/view/2752'.

John N. Schumacher, “Recent Perspectives on the Revolution,” Philippine Studies 30, no. 4 (1982): 445–92; Soledad Borromeo-Buhler, “The Inquilinos of Cavite and Filipino Class Structure in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Asian Studies 21 (1983): 41–58; Palanco, “The Tagalog Revolts of 1745 According to Spanish Primary Sources.”

Barangay: the smallest political unit in the Philippines (Philippine Statistical Authority, psa.gov.ph). It is defined as “a unit of administration in Philippine society consisting from fifty to one hundred families under a headman” (Merriam-Webster.com; “Barangay.”).

Gaspar de San Agustín, “De los sucesos hasta la retirada de Limahón a Dongalo; de su idea a Pangasinán, donde pobló y se intituló rey de aquella provincia, dándole los naturales la obediencia,” Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas / Conquest of the Philippine Islands, 1565-1615, ed. Pedro G. Galende (Manila: San Agustín Museum, 1998), 664-669.