Jesuit Misconduct, Imperial Loyalty, and European Insecurity in Fray Jaime Tarin’s Letter to Fray Álvaro de Benavente

By Carlos Joaquin Tabalon

RAL Essay Writing Contest: First Place

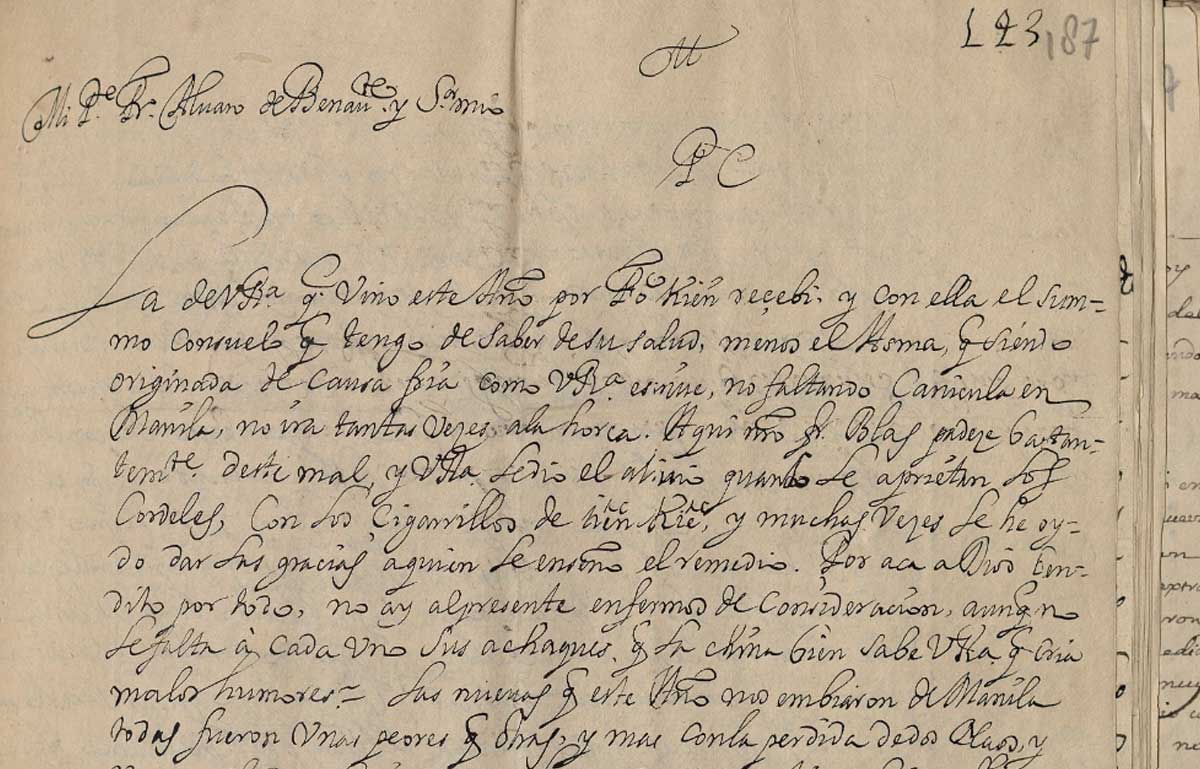

On November 20, 1694, Fray Jaime Tarin, the Franciscan provincial commissary in Canton (now Guangzhou), wrote a correspondence to Fray Álvaro de Benavente, a high-ranking Augustinian who was the titular bishop of Ascalón and the apostolic vicar of Kiangsi (now Jiangxi).[1] At Tarin’s time of writing, Benavente was in Manila. Fray Tarin’s letter is considerably short, having only a length of three pages. Yet the letter’s conciseness should not put off those who are looking for interesting material. Indeed, along with many other contents of the San Agustin Convent’s library digitally reconstructed and repatriated by the collaboration of different international institutions,[2] the information that can be extracted from Tarin’s letter invites careful and critical scrutiny.

The letter begins with Tarin first bringing up the matter of health; he mentions that many missionaries were experiencing illnesses such as asthma, and he echoes Benavente’s diagnosis that China was a breeding ground for “bad humors.”[3] Tarin credits Divine Providence for Benavente’s discovery of an apparently effective kind of cigarette to treat asthma, but also attributes the “strong hand of the Lord”[4] for the missionaries’ persistent difficulties, which included the repercussions of the loss of three Acapulco-bound maritime vessels over the past two years.[5] The ill-fated ships did not just carry valuable merchandise and financial resources, but were also bringing missionaries’ letters which reported on-the-ground conditions in the missions in China and, more importantly, which requested support from the metropole. The Manila-Acapulco route, apart from being an important intercontinental trade route which facilitated commodity exchange between Asia and the Americas, also served as a critical conduit in the wider network of information channels between the missionary frontier in East and Southeast Asia and the center of power in Europe, with Spanish America serving as an intermediary point in the case of the Manila-Acapulco route.[6] Disruptions in the Manila-Acapulco maritime route would render both metropole and periphery uninformed. In Tarin’s account, the Spanish monarchy in Madrid and the Holy See in Rome – the Spanish missionaries’ superiors owing to the patronato real – could not act on the missionaries’ pleas for help because of the three ships’ ill fates.[7]

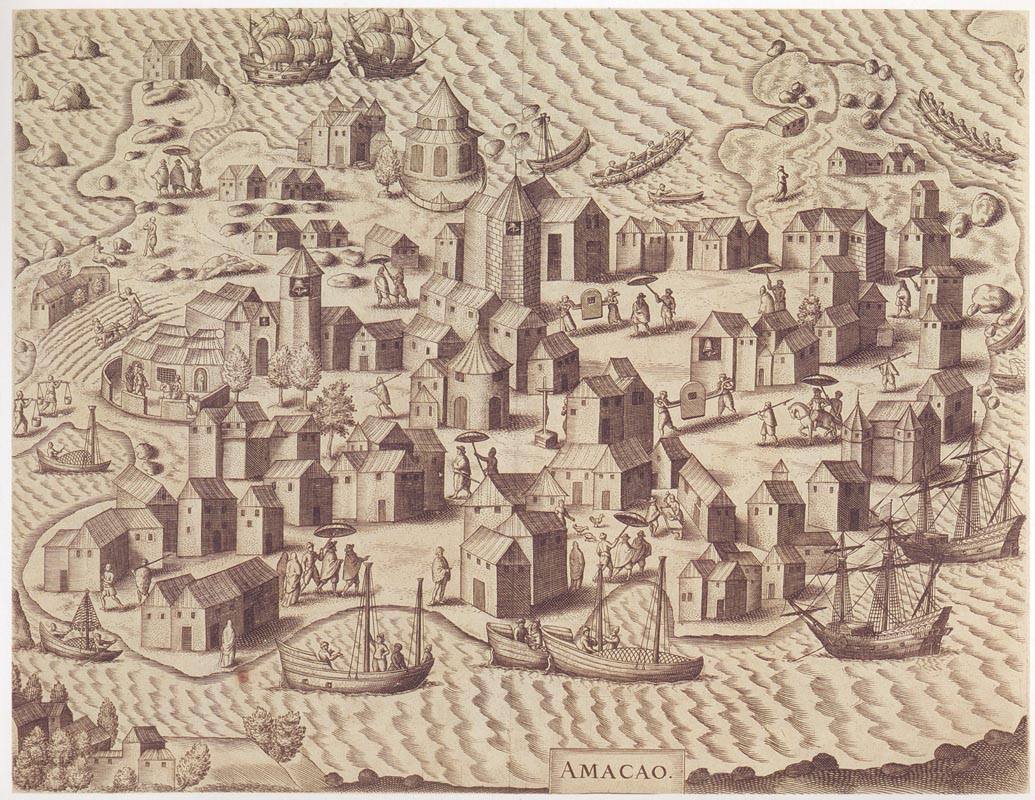

With no information flowing in the Spanish-controlled Manila-Acapulco route, the missionaries in China had to rely on information which came by way of the Portuguese-controlled Indian Ocean route. However, Tarin attests that information that came via the Portuguese route was unreliable, thus adding to the missionaries’ confusion. For instance, Tarin narrates that the Portuguese Jesuits in Macau apparently fabricated a certain decree, making it look like it was issued from the Church’s seat of power in Rome. The Jesuits posited that two of their confreres, Father Francisco Spinola[8] and a certain Father Sa, were in possession of this supposed Rome-issued decree in their journey from Rome to China. Father Spinola died on the trip, leaving Sa with the decree until his arrival in Macau. However, Tarin contends that what Spinola and Sa actually brought were a letter from the pope and a gift all meant for the Chinese emperor, Kangxi, in gratitude for allowing evangelization in China. The Jesuits were never able to provide a tangible copy of this supposed decree.

The provisions of this spurious decree had significant repercussions in the missions in China, as it ordered the revocation of apostolic vicariates. The Augustinian bishop of Macau, João de Casal,[9] cited the decree to justify his removal of a certain Don Luis de Cisse as apostolic vicar and replacing him with Father Carlo Giovanni Turcotti, a Jesuit.[10] Because he was not presented a physical copy of the revocatory decree, Cisse did not comply with Casal’s order, and he ordered the missionaries in China not to display Bishop Casal’s order in their respective churches. The Jesuits did not comply with the embattled Cisse’s instructions. Tarin tells Benavente that some missionaries were of the opinion that the elusive decree was prejudicial to non-Portuguese, non-Jesuit missionaries, and that Bishop Casal was executing the decree’s provisions against his own will, thus giving credence to the allegation that the Portuguese Jesuits fabricated the decree for their own interest. Amidst the cacophony of the controversy, Tarin implores Benavente to let the former know whether the latter gets wind of any developments in Manila with regard to missionary jurisdictions in China.

Tarin goes on to concisely narrate another controversy where the Jesuits in China again took center stage; this was the issue involving French and Portuguese Jesuits. To Tarin’s knowledge, the French Jesuits enjoyed great favor from the Kangxi Emperor that he granted them a large land concession to allow them to construct a large church. In response, Father Tomás Pereira, a Portuguese Jesuit who was also close to the Kangxi Emperor,[11] publicly declared that any Christian who was to be in contact with the French was to be excommunicated. Tarin deplores the rivalry developing into a public scandal, expressing alarm that the upper echelons of the Qing imperial court already knew what an excommunication entails. He then blames the Kangxi Emperor’s playing of both sides against one another for fanning the flames of the rivalry between the French and Portuguese Jesuits, warning that the rivalry, if left unchecked, would doom evangelization efforts in China.

On the surface level, Tarin’s letter may be simply understood as a missionary confiding to a fellow missionary the many challenges of evangelization in a distant land. Asthma induced by the “sickening” environment of the “Orient,” galleons carrying necessary information for the metropole meeting ill fates, and conflicts between missionary orders in which the Chinese emperor had a role in exacerbating – all of these conspired to derail the missionary enterprise in China which generations of European clergymen have been dreaming to make a reality.[12] That Tarin deeply trusted Benavente by burdening the latter with all this sensitive information is clear; Tarin stated, at the end of his letter, that “I have gone on long enough in this letter, and because it may be that I will not write so much to others.”[13] Nevertheless, Tarin also requests Benavente to spread everything that the former told in this letter to the latter’s trusted friends and whoever wanted to know what was happening in China. Tarin’s epistolary message to Benavente is thus nothing short of a cry for help for the latter to use his position as a high-ranking Augustinian official based in Manila to make known to everybody the rather unenviable situation which the missionaries were facing in China. Tarin had full confidence in Benavente, as the latter provided the former help in dealing with the missionaries’ asthma; thus, in the same manner, Tarin hoped that, through Benavente, the necessary help would eventually come to relieve the missionaries of their many difficulties.

There is more to Tarin’s letter than what is explicitly said. Reading against the grain, Tarin’s correspondence may be seen as an encapsulation of his views as a Franciscan and as a Spaniard on what for him constituted proper missionary behavior. As can be seen in Tarin’s account, the Jesuits figured heavily in the controversies. That Tarin, a Franciscan, confided all of these controversies to Benavente, an Augustinian, is in itself significant; Tarin engaged in othering the Jesuits, perhaps not least because, relative to other religious orders, it was the Jesuits who were at an advantageous position in China. Talking about the Jesuits’ controversies and consequently painting them in a bad light probably gave Tarin a kind of confirmation bias that non-Jesuit missionaries like him were the ones who were sincere in doing missionary work in spite of their many difficulties, unlike the Jesuits who resorted to fabricating revocatory decrees from the Holy See or who were too engrossed in petty rivalries based on one’s country of origin all for the sake of gaining a greater foothold in China. Tarin’s relish in recounting the Jesuits’ controversies is evident in the part when, in spite of acknowledging that Benavente already knew of the scandalous French-Portuguese rivalry among the Jesuits, he nevertheless still narrates what transpired in the said controversy.

Although Tarin sought to distinguish himself from the ways of the French and the Portuguese Jesuits who factionalized because they came from different European kingdoms, quite ironically, Tarin also fell for the same tendency. For one, Tarin confided to Benavente, who was also a fellow Spaniard. Moreover, Tarin perceived that whatever information which came by way of the Spanish Pacific route was more reliable and free from deception in contrast to the Portuguese-controlled Indian Ocean route, as exemplified in his request to the Spanish Manila-based Benavente to notify him of legitimate news with regard to the jurisdictional issues that hounded the missionaries in China given that Portuguese clergymen were behind the revocatory decree deception. Tarin’s discreet anti-Portuguese sentiment is proof that imperial loyalty was significantly intertwined with missionary work, in accordance with Ricardo Padrón’s observation on the relationship of missionary work and the intra-Iberian rivalry between Spain and Portugal: “Each empire had its ecclesiastical allies, particularly within the missionary orders, whose ambitions were inextricably caught up with the interests of the crown that sponsored their work.”[14] In short, loyalty to one’s particular sovereign thus greatly influenced the universalist ideal of missionary work.

If it was already difficult enough for missionaries to draw a line between their imperial loyalty and their religious identity, it was even more difficult for missionaries to detach themselves from the early modern European tendency to look at non-European peoples as inherently inferior. It is a given historical fact that the Europeans felt that their encounter with non-Europeans would inculcate in the latter the “civilized” ways of the former; in the case of evangelization, this would mean abandoning “uncivilized” ways of “pagan” beliefs.[15] Nonetheless, the missionaries were aware that the fate of the missionary enterprise greatly depended on the way they and their civil official counterparts conducted themselves in front of the non-Europeans. In the missionaries’ perspective, evangelization could only be made possible if they themselves practiced proper behavior and strongly enjoined others (especially their civil counterparts who tended to be more abusive) to be of the same moral standing as them.[16] Thus, Tarin considered Pereira’s excommunication threats as an embarrassment because the incident undermined the notion that European missionaries were above worldly politics by avoiding scandalous behavior. In Tarin’s view, such politicking perpetrated by no less than missionaries themselves eroded, in the eyes of non-Europeans, the credibility of Christianity to offer a more “civilized” manner of doing things.

The irony in the Europeans’ view that they could teach “inferior” non-Europeans their “superior” ways is that non-Europeans could never achieve equal stature with their European “teachers.” In the realm of evangelization, there was a split; some were of the opinion that some non-Europeans, particularly the Chinese and the Japanese, could become genuine converts, while others remained adamant that non-Europeans could never totally grasp the meaning of Catholic doctrine.[17] This is why Tarin felt that excommunication was something which the Qing imperial court should be shielded from learning, because he feared that shallow knowledge of such weighty doctrinal matters would lead to irresponsible acts from Chinese authorities which could altogether compromise the missionary enterprise. But in spite of the missionaries’ efforts to limit the imperial court’s influence in dictating the terms of evangelization in China, they found themselves accommodating to the demands of the imperial court to sustain the missionary enterprise, as was the case in the French and Portuguese Jesuits’ squabble for the Kangxi Emperor’s favor. Tarin blaming the emperor for being the cause of the Jesuits’ rivalry drawn on nationality lines is a tacit admission that power over evangelization efforts did not rest solely on the missionaries’ hands, but had to be contested and negotiated with the Chinese emperor.

In the end, Tarin’s letter to Benavente is illustrative of how missionary dreams of a grand evangelization of the Celestial Empire were checked by realities on the ground; most especially, the human limitations of the missionaries who, as products of their time and place of origin, espoused problematic views and made problematic decisions in the hope of securing evangelization inroads in China.

Carta de Fray Jaime Tarin a Fray Álvaro de Benavente desde Cantón sobre la pérdida de comunicación por el lado español a causa de la pérdida de dos naos

Concerns the animosity between the Portuguese and the French, and Father Pereira's order of excommunication to all Christians who communicate with the French

Bibliography

“Diccionario de Autoridades(1726-1739).” Accessed June 7, 2025. https://apps2.rae.es/DA.html.

Laliberte, Marissa. “These Butter Cookies from the Philippines Supposedly Have Healing Powers.” Reader’s Digest (blog), October 9, 2017. https://www.rd.com/article/san-nicolas-cookies/.

Mawson, Stephanie. “Slavery, Conflict, and Empire in the Seventeenth-Century Philippines.” In Slavery and Bonded Labor in Asia, 1250-1900, 256–83. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004469655_012.

Mentrida OSA, Alonso de. Vocabulario de Lengua Bisaia, Hiligueyna, Yharaia de La Isla de Panai y Sugbu, y Para Las de Mas Islas, 1637.

Mojares, Resil B. “The Life of Miguel Ayatumo: A Sixteenth-Century Boholano.” Philippine Studies 41, no. 4 (1993): 437–58.

Scott, William Henry. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo De Manila University Press, 1994.

———. “Cracks in the Parchment Curtain.” Philippine Studies 26, no. 1/2 (1978): 174–91.

Notes

For more biographical information on Fray Jaime Tarin, see Eusebio Gómez Platero, Catálogo biográfico de los religiosos franciscanos de la provincia de San Gregorio Magno de Filipinas desde 1577 en que llegaron los primeros a Manila hasta los de nuestros días (Imprenta del Real Colegio de Santo Tomás, 1880), 299, http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000143474&page=1. For more biographical information on Fray Álvaro de Benavente, see Isacio Rodríguez Rodríguez, Historia de la provincia agustiniana del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús de Filipinas, vol. 2, 22 vols. (Manila, 1966), 296–97. For more information on Fray Tarin’s other encounters with Fray Benavente, see Rodríguez, Historia, vol. 7, 270; Rodríguez, vol. 9, 397.

For more information about the digital repatriation project, see Department of Philippine Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, “Reclaiming the Lost Archive of the Convento de San Agustin,” 2025, https://1762archive.org/

Quoted from Tarin, “Carta de Fray Jaime Tarin a Fray Álvaro de Benavente desde Cantón sobre la pérdida de comunicación por el lado español a causa de la pérdida de dos naos”, 380r.

Quoted from Tarin, “Carta”, 380r.

For more on information on the three ill-fated ships, see Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, eds., “Extracts from Jesuit Letters,” in The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803: Explorations by Early Navigators, Descriptions of the Islands and Their Peoples, Their History and Records of the Catholic Missions, as Related in Contemporaneous Books and Manuscripts, Showing the Political, Economic, Commercial and Religious Conditions of Those Islands from Their Earliest Relations with European Nations to the Close of the Nineteenth Century, vol. 41, 55 vols. (The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1906), 36, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer&cc=philamer&q1=blair&op2=and&op3=and&rgn=works&rgn1=author&rgn2=title&rgn3=title&idno=AFK2830.0001.041&didno=AFK2830.0001.041&view=image&seq=40&node=; Casimiro Diaz, “The Augustinians in the Philippines, 1670–1694,” in Blair and Robertson, vol. 42, 307–8, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer&cc=philamer&q1=blair&op2=and&op3=and&rgn=works&rgn1=author&rgn2=title&rgn3=title&idno=AFK2830.0001.042&didno=AFK2830.0001.042&view=image&seq=311&node=. In brief, these three (3) ships were the following; (1) a patache which served as an arribada or a vessel dispatched in advance, which was burned in the port in the Mariana Islands, (2) the Santo Cristo de Burgos which disappeared after departing Naga in July 1693, and (3) the massive San José which sank off the coast of Lubang Island because of a storm.

For discussions on how the Spanish Empire perceived and utilized the Manila-Acapulco route as a means to further the aims of missionary work, see Ricardo Padrón, The Indies of the Setting Sun: How Early Modern Spain Mapped the Far East as the Transpacific West (The University of Chicago Press, 2020), 180–2, 185, 192–94, 202–3, 214–15, 227–31.

The patronato real (royal patronage) authorized the Spanish Empire to exercise jurisdiction on ecclesiastical affairs in its overseas possessions. In effect, missionaries reported to both the Spanish monarchy and their traditional superior, the Holy See.

His surname is spelled out as “Espinola” in the document. See Tarin, 380r, 381v.

For more biographical information on Bishop João de Casal, see Diocese de Macao, “D. João de Casal (1690-1735),” January 20, 2017, https://www.catholic.org.mo/en/list-5/14.

For more biographical information on Father Carlo Giovanni Turcotti, see David M. Cheney, “Father Carlo Giovanni Turcotti,” Catholic-Hierarchy, February 25, 2024, https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/bishop/bturcotti.html

For a treatise on Father Tomás Pereira’s missionary ventures in China, see Artur K. Wardega and António Vasconcelos de Saldanha, eds., In the Light and Shadow of an Emperor: Tomás Pereira, SJ (1645–1708), the Kangxi Emperor and the Jesuit Mission in China (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012).

Christina H. Lee, ed., Western Visions of the Far East in a Transpacific Age, 1522-1657 (Routledge, 2012), 3–4; Charles R. Boxer, “Portuguese and Spanish Projects for the Conquest of Southeast Asia, 1580–1600,” Journal of Asian History 3, no. 2 (1969): 118–36, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41929968.

Quoted from Tarin, 382r.

Quoted from Padrón, 186.

Boxer, The Church Militant and Iberian Expansion, 1440-1770 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 39–40.

The argument in this statement is heavily based on John N. Schumacher, “Bishop Domingo de Salazar and the Manila Synod of 1582,” in Growth and Decline: Essays on Philippine Church History (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2009).

For discussions on the debates surrounding the matter of Chinese and Japanese conversion, see Liam Matthew Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724 (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007); Padrón, 170, 176, 180, 187, 195, 197–98, 201–3, 211–12, 214–15, 219, 227. For a discussion on European views on the question of ordaining Chinese and Japanese priests, see Boxer, The Church Militant and Iberian Expansion, 23–27.