2024 / 1928

The Year 1928

The Books of 1928

20 hrs. 40 minutes by Amelia Earhart

“Possibly the feature of aviation which may appeal most to thoughtful women is its potentiality for peace. The term is not merely an airy phrase. Isolation breeds distrust and differences of outlook. Anything which tends to annihilate distance destroys isolation, and brings the world and its peoples closer together. I think aviation has a chance to increase intimacy, understanding, and far-flung friendships thus.”

Part autobiography, part expedition diary, famed aviationist Amelia Earhart’s first book 20 hrs. 40 minutes details not only her experience as the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean as a passenger in the Friendship, but also how her love of flight took off. Only 150 copies of this special edition were printed; the book is not only signed by Earhart, but also includes a small silk American flag that traveled with the pilot on her journey from Boston to Wales. Her disappearance while flying over the Atlantic in 1937 has borne decades of speculation and countless conspiracy theories, making it easy to forget the impact Earhart had on the commercialization of air travel for everyone and the opportunities available to women aviators.

A Mirror for Witches by Esther Forbes

“It has long been known that, on occasions, devils in the shape of humanity or in their own shapes (that is, with horns, hooves, and tails) may fany mortal women.”

Ester Forbes is best known as a children’s author and historian, winning the Pulitzer Prize in history for her work Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (1942) in 1943 and the Newberry Award for young adult novel Johnny Tremain (1943) in 1944. Her second novel, A Mirror for Witches, is in the same vein as her other early-America historical fiction, but with a somewhat darker twist. Forbe’s main character Doll Bilby (also referred to as “Bibly’s Doll”), is the adopted daughter of a Puritan farmer who many in her small Massachusetts colony believe is in league with the devil. By writing the novel almost fully outside Doll’s perspective, Forbes leaves the reader constantly wondering how much is true about Doll and how much is suspicion born out of prejudice. A precursor to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, Forbes work is atmospheric, strange and captivating.

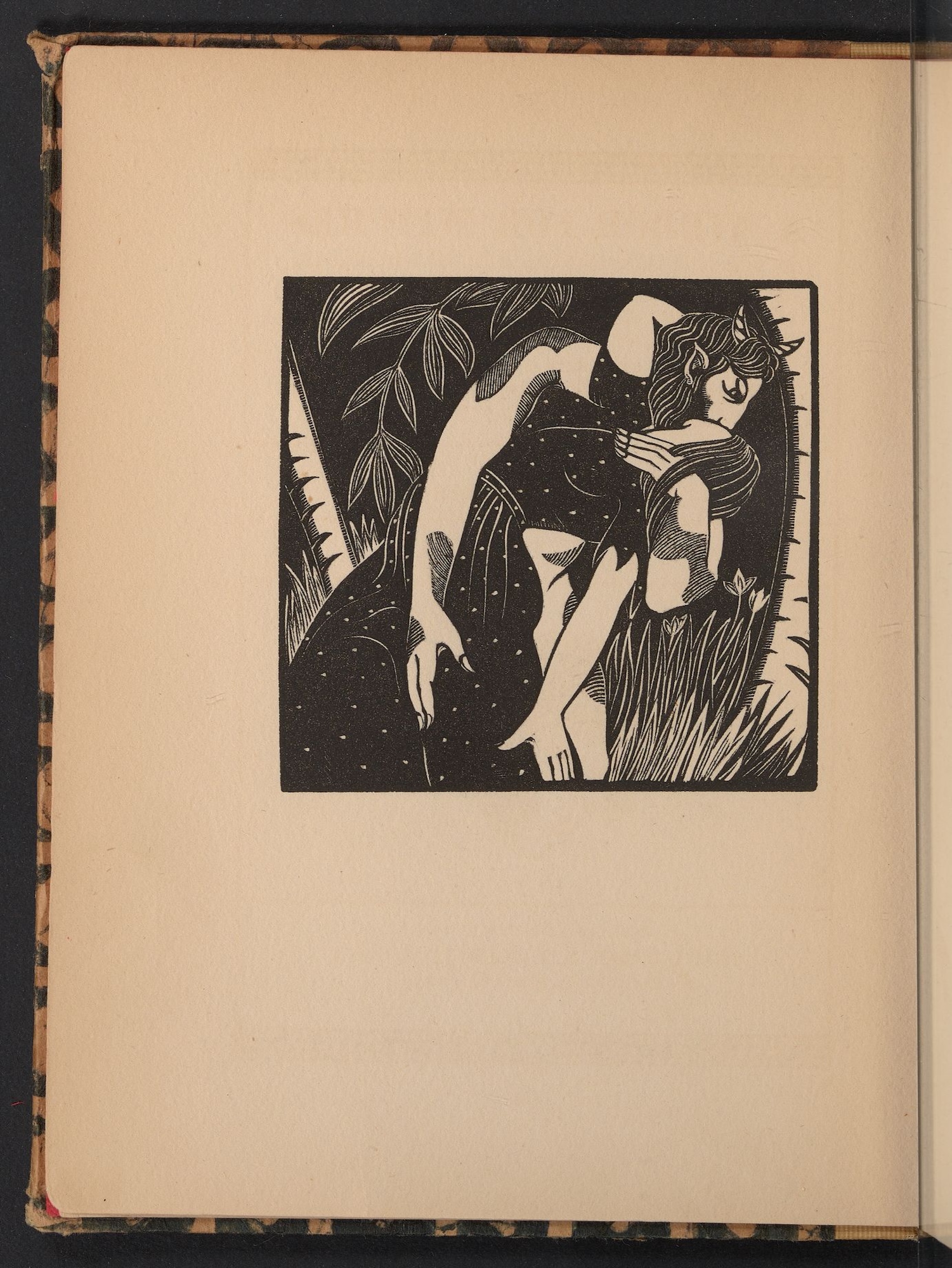

Armed with Madness by Mary Butts

“Pine-needles are not easy to walk on, like a floor of red glass. It is not cool under them, a black scented life, full of ants, who work furiously and make no sound. Something ache din Carston, a regret for the cool brilliance of the wood they had left, the other side of the hills, on the edge of the sea”

English Modernist Mary Butt’s literary genius was somewhat overshadowed by lurid tales of her personal life. She had romantic relationships with men and women, divorced twice, and suffered from addiction to alcohol and opium. However, her second novel, Armed with Madness has been called a “masterpiece of modern prose”. Amongst a story involving a coterie of post-war rural Britons investigating the mysterious appearance and movements of a jade cup, Butts utilizes a free-flowing prose style evocative of that often born through the spiritualist practice of automatic writing. Comparable to the formal innovations seen in Joyce’s Ulysses and the referential style of Eliot’s The Wasteland, Butts’ novel explores the tensions between the individual and the collective, abundance and lack, and the known and the unexplained to reflect on the modern condition and post-war trauma.

Black Folk Tales by Eric Berry

Written by Erick Berry, an American socialite and explorer, Black Folk Tales illustrates and retells oral tales of the Hausa people of North Nigeria. Born Evangel Allena Champlin in 1892, Berry likely collected these stories as she traveled unaccompanied along the West coast of Africa during the early 20th century. Her travels enabled her to join the Society of Women Geographers, established in 1925. As a recent graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Berry initially traveled to Nigeria to paint portraits of the “native population,” yet soon began documenting her experiences for American newspapers and travel magazines. Through her writings, she hoped to advance a “positive and progressive view of the continent and its people.” Black Folk Tales captured her engagement with the Hausa people, with whom she developed a friendly relationship. As the first in a series of books about Africa, authored and illustrated by Berry, Black Folk Tales was written explicitly for White audiences, with the intention of portraying Africans as peers, capable of leadership and sound judgment. Her rhetoric is often essentialist and antiquated in tone, however scholars have argued that Berry subversively used such a tone to create space for resistant readings of her work and to socialize her readers against racism and stereotypes.

Black Majesty by John W. Vandercook

These men were kings, albeit they were black,

Christophe and Dessalines and L'Overture;

Their majesty has made me turn my back

Upon a plaint I once shaped to endure.

These men were black, i say, but they were crowned

And purple-clad, however brief their time.

Stifle your agony; let grief be drowned;

We know joy had a day once and a clime.Dark gutter-snipe, black sprawler-in-the-mud,

A thing men did a man may do again.

What answer filters through your sluggish blood

To these dark ghosts who knew so bright a reign?

"Lo, I am dark, but comely," Sheba sings.

"And we were black," three shades reply, "but kings."

Although Haiti played a significant role in the Harlem Renaissance, serving as an international example of Black self-determination in the early 20th century, broader global interest and fascination with the Black Republic fully took hold in the mid-1920s, as the lengthy and controversial U.S. Occupation of Haiti (1915-1934) began receiving considerable public attention. Haiti inspired an outpouring of artistic expression in the United States, arguably Historian Mary Renda contends, giving "Americans the opportunity to reimagine their own nation and their own lives."

John W. Vandercook’s Black Majesty capitalized on the public fascination with Haiti, and in particular with the historical figure of King Henri Christophe. While short-lived, the Kingdom of Hayti (1811-1820) served as a central flashpoint of Black self-governance in the 19th century, ushering in the rapid development of trade, industry, culture, and education. It is a period of Haitian history little known outside of the island. Designed by Mahlone Blaine, the striking illustrated book cover prominently depicts King Christophe and accentuates his coat of arms–the crowned bird on the bed of claims–which goes on to become incorporated into the Haitian flag.

They stood and watched

The dark square-shouldered prisoner, the great flight-

feathers

of the dragged wing were worn to quills, and beetles

Crawled by the weaponed feet, yet the dark eyes

Remembered their pride. Hood said, “you ough to kill

him”

Set against the rugged backdrop of California’s coastal town of Big Sur Robinson Jeffers' poem Cawdor combines the tropes of classical epics with references to Shakespeare to paint a picture of familial tragedy. A mid-century icon of the environmental movement, Jeffers coined the term “inhumanism” to describe his belief that human beings are too self-centered to see the true beauty in the world around them or to realize the potential for beauty in themselves. In this belief, Jeffers set himself apart from his contemporaries, but his use of long verse was more narrative than that of poets like Ezra Pound and in setting his work in the West – not the rolling hills of England or the streets of Harlem – he reflected a different kind of modernist commentary. Despite his success in his time, Jeffers' work has faded from public engagement. His words may have new relevance, however, as humanity grapples with the increasing threat of climate change.

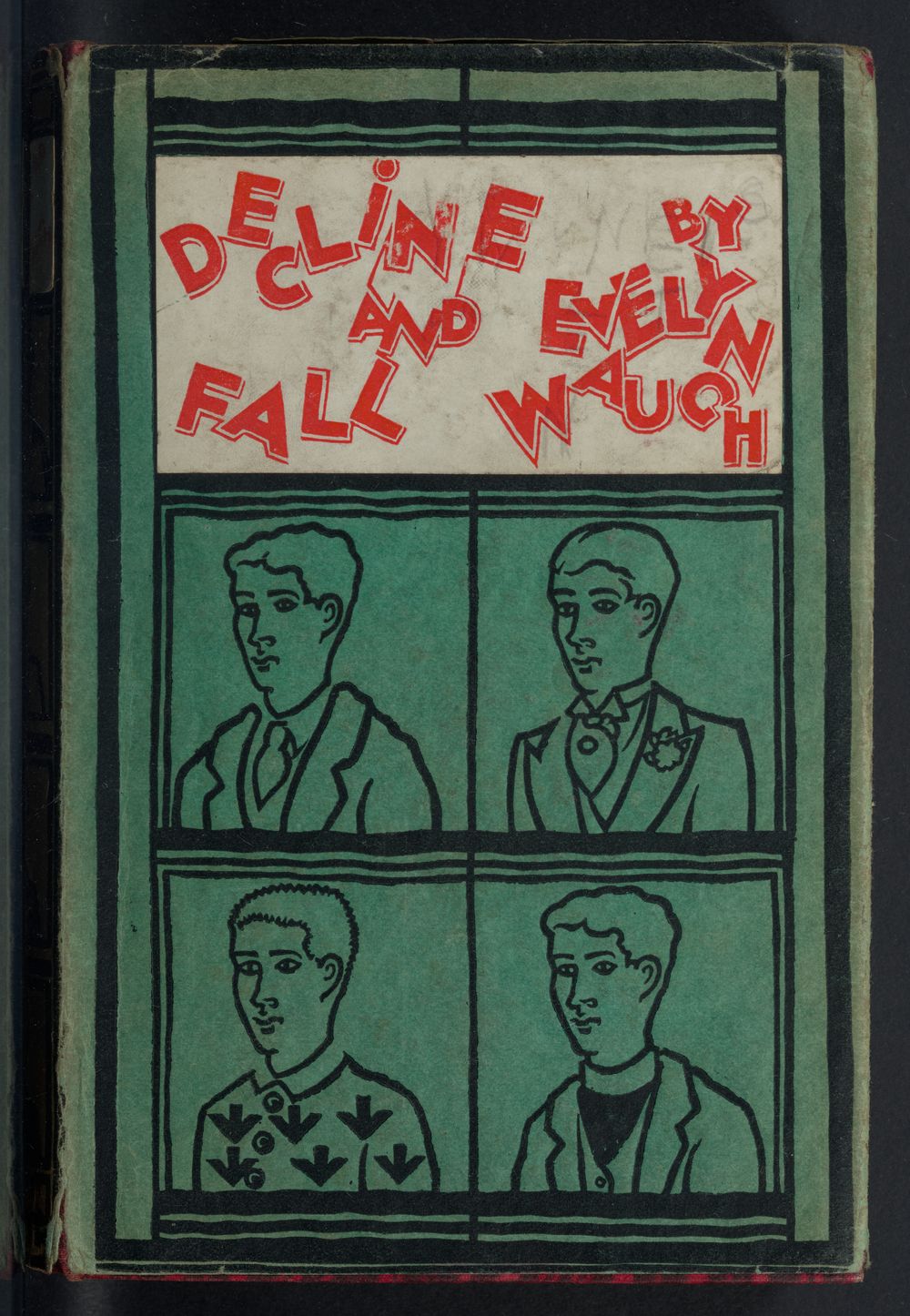

Decline and Fall; An Illustrated Novelette by Evelyn Waugh

English author Evelyn Waugh’s first published novel is a biting satire of British high society. Inspired by experiences growing up in the British school system, Waugh’s main character, Paul Pennyfeather, is wealthy but clueless, getting out of trouble as easily as he gets into it. Paul’s money cocoons him from consequences but also from insight and awareness. The title, a play on Edward Gibbons' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, speaks to Waugh’s clever commentary on the modern decline he saw before him. Today Waugh, who is remembered for his sharp writing and unparalleled wit, set the stage for satire in the 20th century.

Lady Chatterley's Lover by D.H. Lawrence

Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes. It is rather hard work: there is now no smooth road into the future: but we go round or scramble over the obstacles. We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen.

First privately published in Italy as a limited English-language edition, Lady Chatterley's Lover was an influential yet controversial novel whose plot challenged societal norms. It analyzed both the power dynamics between men and women and the impact of social class on personal freedom. Set in early 20th-century England, it follows Constance Chatterley, who, feeling unfulfilled in her marriage to a paralyzed aristocrat, embarks on an affair with the gamekeeper, Oliver Mellor. Its explicit sexual content and frank portrayal of adultery drew immediate controversy and censorship, resulting in bans in the United States, Canada, Australia, India, and Japan.

In 1960, the work became the center of a landmark obscenity trial when Penguin Books released an unexpurgated edition, marking a pivotal challenge to the long legacy of literary censorship. Lawyers, working on behalf of the publishers, argued that the novel possessed academic merit because of its frank exploration of essential themes of love, desire, and class struggle. Penguin's success at trial confirmed a shift in societal attitudes towards including sexual content in literature and reflected a broader acknowledgment of the artistic and thematic value of works that push boundaries.

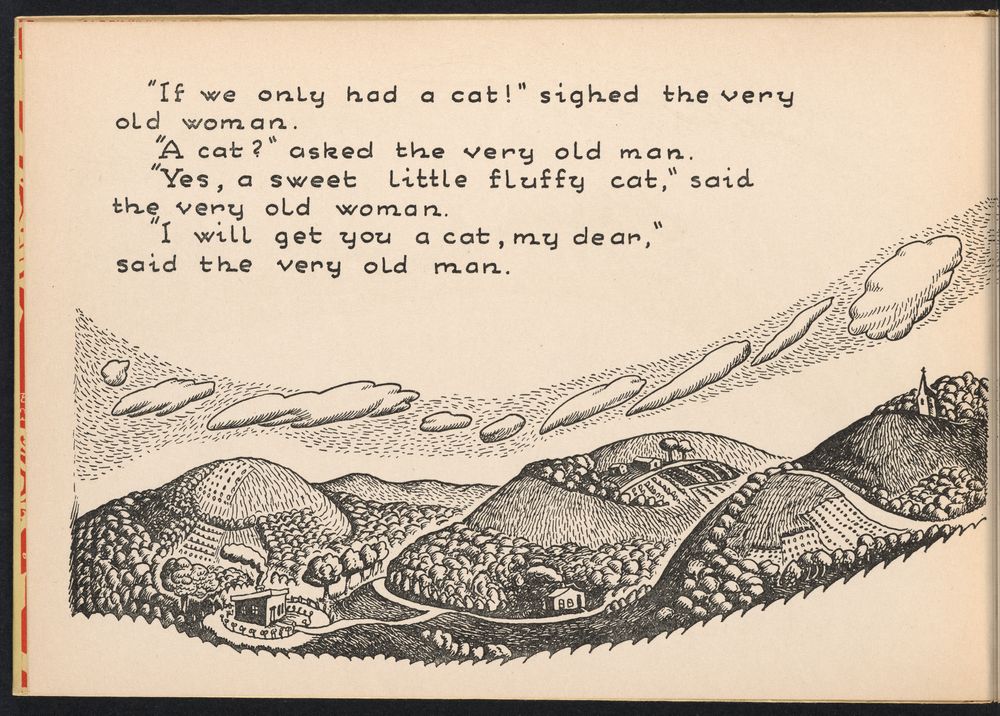

Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág

Cats here, cats there. Cats and kittens everywhere.

Millions of Cats is the oldest American picture book still in print. Written and illustrated by Wanda Gág, the work pioneered the double-page spread, winning the Newbery Honor in 1929, just one year after its publication. Reviewers have noted the innovation, "she used both sides of the page to move the story forward." While it would go on to appear on countless lists of the 100 greatest children’s books, publishers initially rejected the classic. In the children's story, an old man, unable to decide on the perfect cat, instead brings home millions, billions, and then trillions of cats home to his wife. His decision has unintended and sometimes harmful consequences. In the mid-20th century, Gag’s modernist folktale was often banned as its content was viewed as having underlying communist sympathies because of its message warning against the harms of excess consumption.

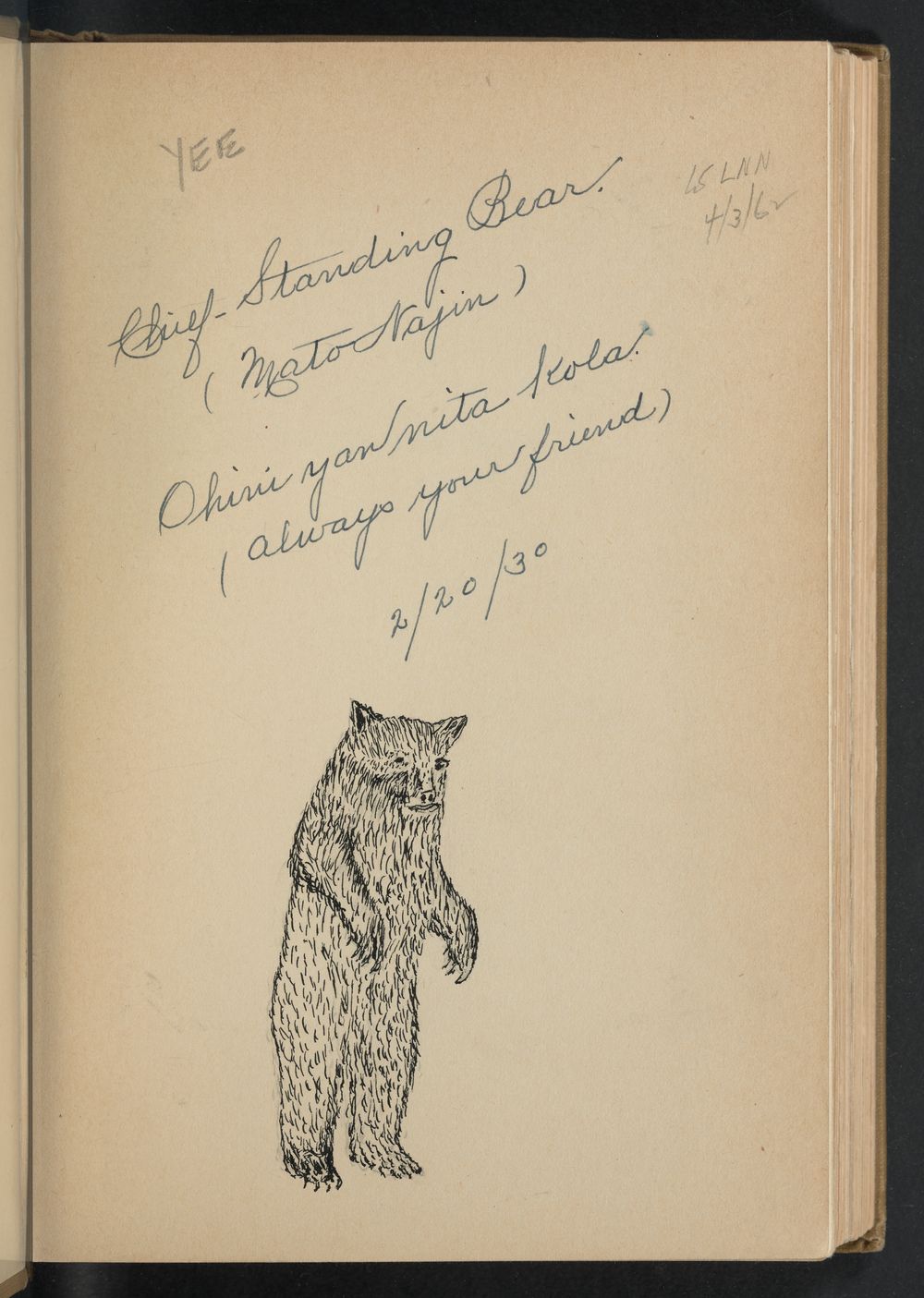

My People, the Sioux by Luther Standing Bear

The Indian is bright, and he is capable of holding good, responsible position if he is only given a chance.

And why not give the Indian that chance?

My People, the Sioux holds the distinction of being one of the first published books about Indigenous people from the Indigenous point of view written by an Indigenous person. The book’s author, Luther Standing Bear, was a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe born in 1868 on the Pine Ridge Reservation in the territory currently called South Dakota. After surviving an education at the Carlisle Indian School, he opened a dry goods store in Pine Ridge before joining the infamous Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show with his family. He briefly acted as the chief of the Oglala Lakota before moving to present-day California to pursue a career in the movie industry, partnering with Olympic gold medalist Jim Thorpe to establish the Indian Actors Association. In 1928, he published his first of four books, My People, the Sioux, with the help of his niece Was-te-win and her husband, William Dittmar, detailing his personal experiences and tribal history. The book was part of a broader effort to build support for the Indian New Deal (later passed as the Indian Reorganization Act) and followed by My Indian Boyhood (1931), Land of the Spotted Eagle (1933), and Stories of the Sioux (1934). Today, Standing Bear is recognized as a leading figure in the Progressive movement, and his writings, including My People, the Sioux, an important resource for cultural heritage and memory. Princeton’s copy has an inscription by Standing Bear written in English and Lakota with a small drawing of a standing bear.

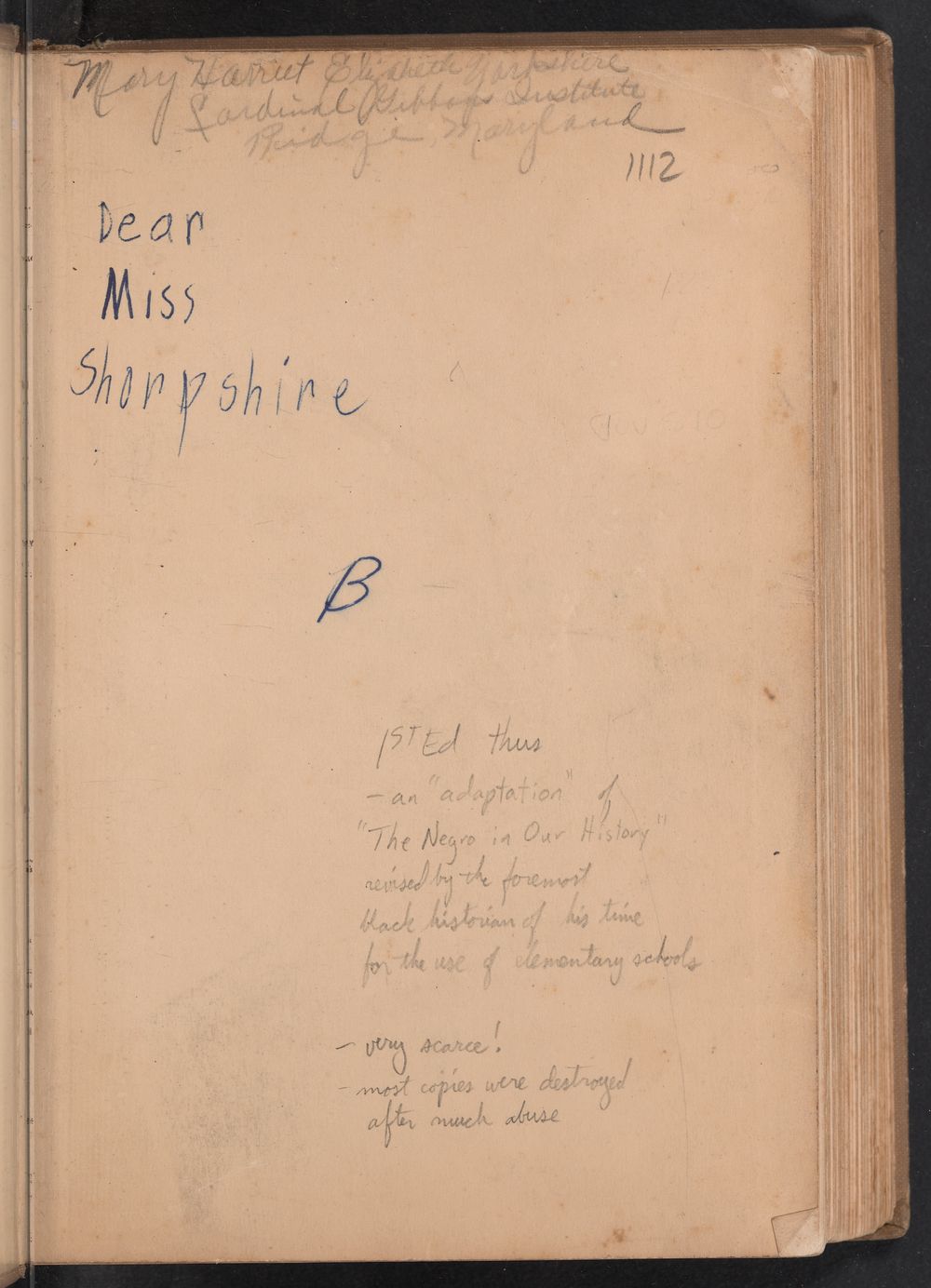

Negro Makers of History by Carter G. Woodson

Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history.

Written by Carter G. Woodson, an influential African American historian and scholar, Negro Makers of History was an adaptation of his earlier work, The Negro in Our History, this time with elementary school-aged children in mind. The original work, published in 1922, was well received, entering ten editions. It garnered praise by Alain Locke for having “brought about a revolution of [the] mind.” Woodson is often regarded as the Father of African-American history for his tireless efforts to increase the visibility of African-American contributions to world history. In 1926, he created the first united Negro History Week, the precursor to Black History Month. As the founding editor of the Journal of Negro History, Woodson developed this textbook-style work to facilitate the historical study of African Americans. The work includes numerous illustrative engravings depicting pre-colonial Africa, the experience of the transatlantic slave trade, Negro participation in the American Revolution, the settlement of Liberia, authors of the Harlem Renaissance, and other topics that Woodson argues are central in the education of black children. A table of content and a lengthy index bookend the nearly 400 page work. The intended purpose was to “facilitate the teacher's task of preparing children to play their part creditably in this new age.” Princeton's copy was likely owned and used by a school-aged child, as indicated by adolescent annotations on the front cover.

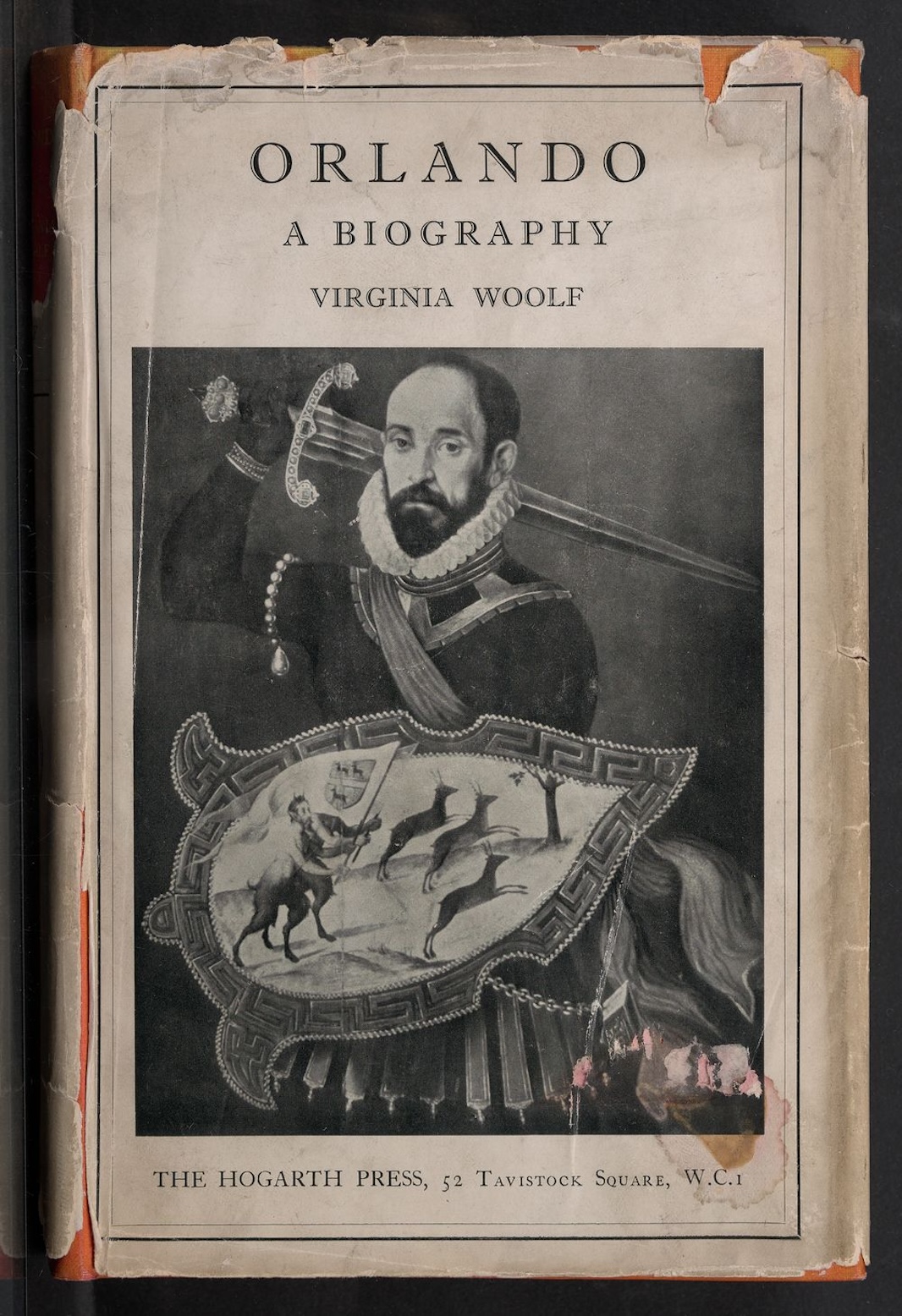

Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf

No passion is stronger in the breast of a man than the desire to make others believe as he believes. Nothing so cuts at the root of his happiness and fills him with rage as the sense that another rates low what he prizes high. He who robs us of our dreams robs us of our life.

Orlando: A Biography was first published in October 1928 by the Hogarth Press, a small publishing outfit founded by Virginia Woolf and her husband, Leonard, to expand Woolf's literary freedom. The groundbreaking novel defies traditional narrative conventions, exploring themes of gender, identity, and time. Readers follow the protagonist, Orlando, a young nobleman in Elizabethan England who, over the course of his centuries-long life, changes sex from man to woman. Scholars consider the novel an early feminist classic for its innovative exploration of gender fluidity and the limitations imposed by societal norms, a radical proposition at its time. The novel, which was initially released as a limited edition of 750 copies, received mixed reviews, with critics praising its innovative narrative style and exploration of gender and identity and others finding it confusing or unconventional. However, it would emerge as one of Woolf's more significant works, and it has been translated into numerous languages and entered multiple editions. This was inscribed by Woolf to British writer and art critic Raymond Mortimer.

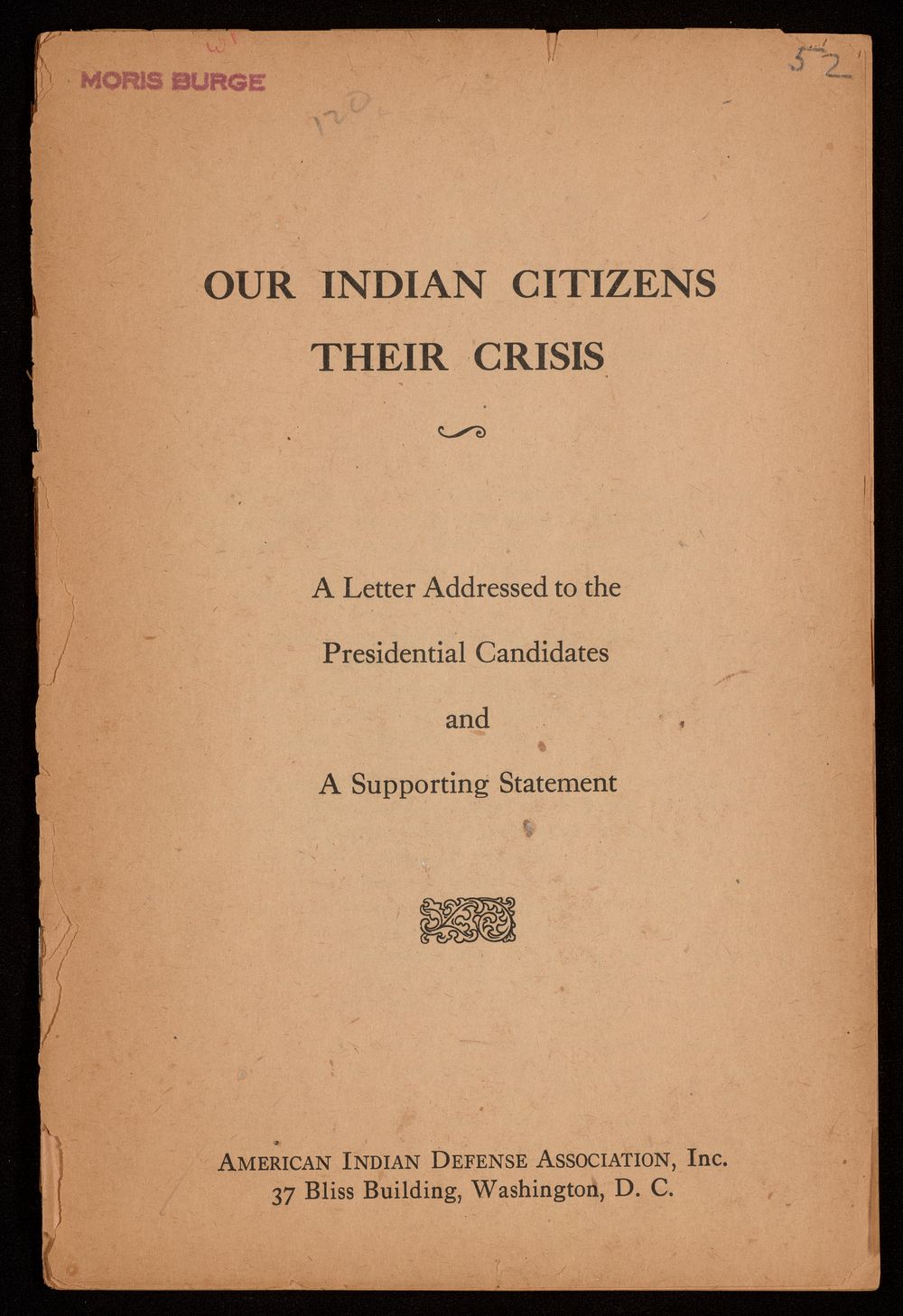

Our Indian Citizens, Their Crisis by The American Indian Defense Association

“The horrors of today may perhaps be parallelled by horrors in the past. The past is irrevocable. The present and future lie in our hands”

Established in 1923, the American Indian Defense Association fought to defend religious freedom and property rights for Indigenous communities across the United States. This pamphlet, addressed “Dear Sir,” is a plea to the American Presidential Candidates for 1928 to attend to the urgent needs of the Indigenous people across the continent, including insufficient food and infrastructure, forced assimilation, and abuse at the hands of law enforcement and governmental agencies. Some of the demands outlined in section ten are still recognizable as necessary today and serve as a reminder of the work that has and has yet to be done to find peace and justice for all residents.

“Somewhere, within her, in a deep recess, crouched discontent. She began to lose confidence in the fullness of her life, the glow began to fade from her conception of it. As the days multiplied, her need of something, something vaguely familiar, but which she could not put a name to and hold for definite examination, became almost intolerable. She went through moments of overwhelming anguish. She felt shut in, trapped.”

The lesser known of Larsen’s two main works (the other being Passing), Quicksand is a complex portrait of a biracial woman in the 1920s searching for peace and belonging in a world with little room for ambiguity. From a fictionalized version of the Tuskegee Institute to the doorstep of her uncle in Chicago, the home of an educated Black family in Harlem, and the white society circles in Copenhagen, Helga Crane runs from one community to another. Hypocrisy, bigotry, and fetishization, however, reveal themselves again and again, but Helga’s maddening restlessness and antagonistic character resist likeability. And yet, Larsen masterfully crafts a sympathetic story with an ending nothing short of heartbreaking. Quicksand demands the reader confront individual tragedy, not just that born from societal or systemic forces, in a way that is jarring and eye-opening. This copy still has its dust jacket, making it particularly rare.

The primary object of this narrative, however, is not for the personal glory, or self praise but rather to perpetuate my achievements on the bicycle tracks of the world, for the benefits of all youths aspiring to an athletic career...

In 1899, Marshall W. “Major” Taylor became the world champion in cycling, making him only the second African American world champion in any sport (following George Dixon’s bantamweight boxing world title in 1890). Taylor documents his experience, including the racial prejudice he encountered throughout his cycling career. Including first-person stories of races, photographs, excerpts from newspapers, and journal coverage, in which he was nicknamed the “Black Cyclone.” After winning the world championship, Major Taylor traveled internationally, racing against and beating many of the world’s best riders. Taylor included the subtitle, “the Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds,” in the hope of providing advice to other Black athletes seeking to blaze their own trail.

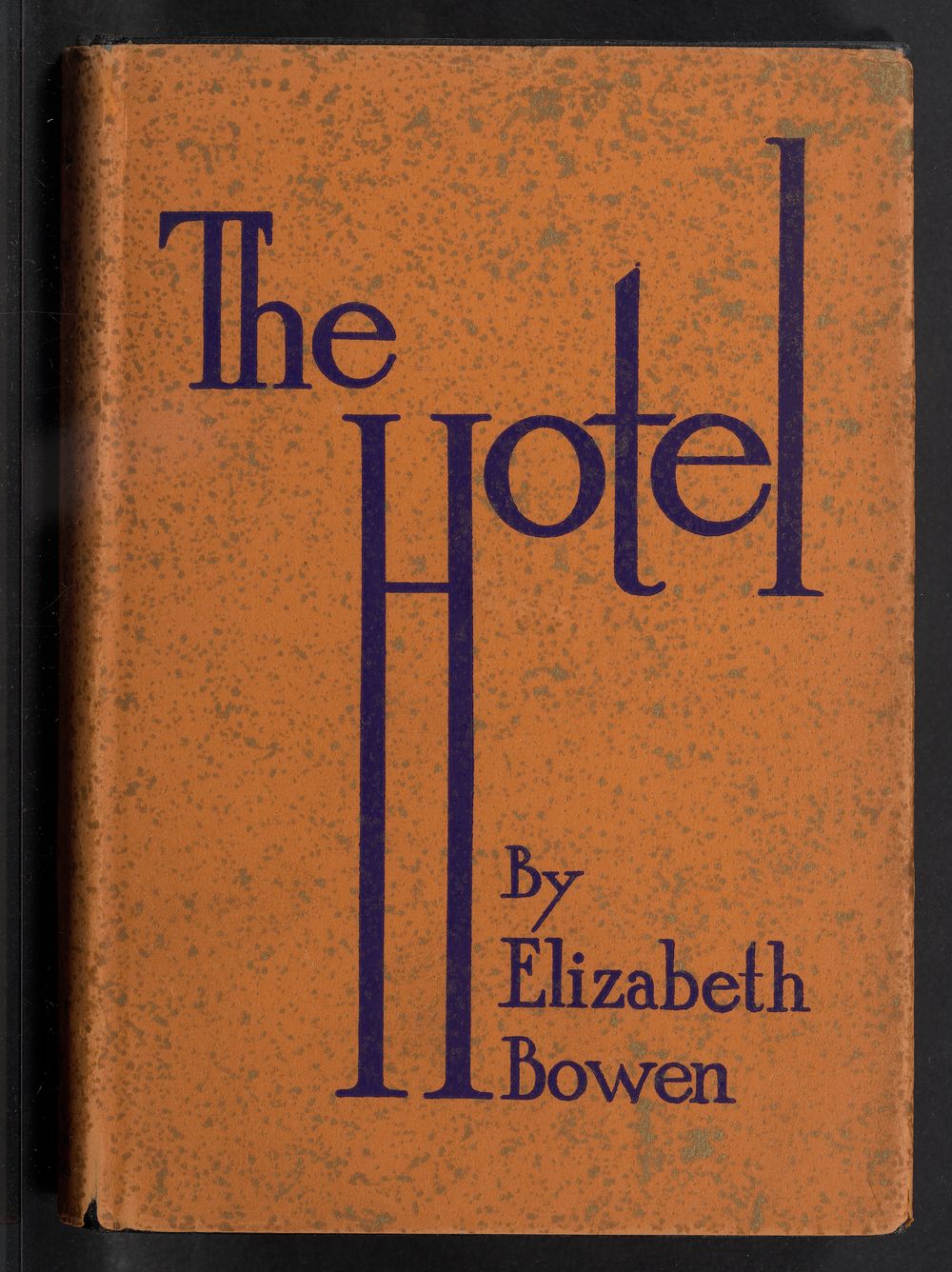

“The view was their own; they were to enjoy the spiritual, crude and half-repellent beauty of that changing curtain, so featureless save for the occasional passing of a ship. They barricaded themselves in from the assault of nonday behind impossible jealousies”

Irish author Elizabeth Bowen’s debut novel The Hotel centers around a group of English tourists on holiday in the French Rivera against the backdrop of World War I. A sister novel to Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and Elizabeth von Arnim’s Enchanted April, Bowen’s book is a slow commentary on British high society through the lens of her character’s interior lives. Her novels cataloged emotions rather than events, making her books a very particular kind of read. Bowen would go on to write ten novels and thirteen short story collections, including Eva Trout, or Changing Scenes, which was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1968.

The Walls of Jericho by Rudolf Fisher

Has any New Yorker confessed to the rest--that when aristocratic Fifth Avenue crossed One Hundred Tenth Street, leaving Central Park behind, it leave its aristocracy behind as well?

The Walls of Jericho was the first novel by Rudolph Fisher, an African-American physician turned celebrated author during the Harlem Renaissance. Fisher, whose second work, The Conjure-Man Dies, would cement his place as a central figure of the era, was described by Langston Hughes as “the wittiest of the Harlem Renaissance writers, whose tongue was flavored with the sharpest and saltiest humor.”

Published in 1928, The Walls of Jericho delves into issues of race, class, and social dynamics in 1920s Harlem. Fisher embraced satire in examining intra-community issues of colorism, prejudice, and class inequality amongst upper and lower-class Harlemites as they pursue different versions of socioeconomic and political advancement. The work features a contemporary dictionary of "Harlemese," a clear allusion to the unique cultural resonance of life in Harlem during the time.

Scholars have argued that Fisher’s work was deeply and critically immersed in W.E.B Dubois’s call to “advance the race.” Indeed, his rhetoric was critical of such discourses, including those that centralized Africa as a referent and a source of identity. Rather than being biologically deterministic, Blackness appeared in Fischer’s work to be experiential. Fisher, who died at age 37, wrote essays, short stories, and novels that often explored the complexities of African-American life and was a regular contributor to various periodicals. The first edition of Wall of Jericho featured a dust jacket and book design by Harlem Renaissance collaborator Aaron Douglass.

Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Dramatic History by Leslie Pinckney Hill

Hayti has come to be a sort of chellenge to the democratic sentiments and pretentionsof our time...it was in Hayti that the greatest of Negros rose up to strike the shackles of slvaery from the limbs and minds of his race, and thus serve mightily the cause of American Independence.

In 35 scenes–told in verse and poetry–this innovative work tells the story of Haitian Revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture. In 1792, the enslaved people in Saint Domingue, France’s more lucrative colony, revolted. Led by Toussaint and later Jean Jacques Dessalines, the revolution lasted – and established Haiti as the world’s first free Black Republic. Author Leslie Pickney Hill’s play sought to frame the legacy of Toussaint and the Haitian Revolution for Black American audiences, hoping to correct the misguided notion that Black people have not contributed to civilization. Regarding the story of Toussaint, he presupposes, “nothing could be more startling to the modern reader than the story of a Negro functioning magnificently, almost sublimely, as a human being exactly like other human beings of the same exaltation.” The history Haytian revolution, both as fact and as interpretation, offered a hearty contradiction to such rhetoric.