Passage to Jackson

After another mob attack at the Montgomery First Baptist Church gathering at which Martin Luther King Jr. spoke on the night of May 21, the again-reconfigured group of Riders prepared to leave Alabama for Mississippi. Unbeknownst to the Riders, Robert F. Kennedy had struck a deal with Alabama and Mississippi officials, agreeing not to intervene in the arrest of the Riders, provided they were given safe passage to Jackson, Mississippi.

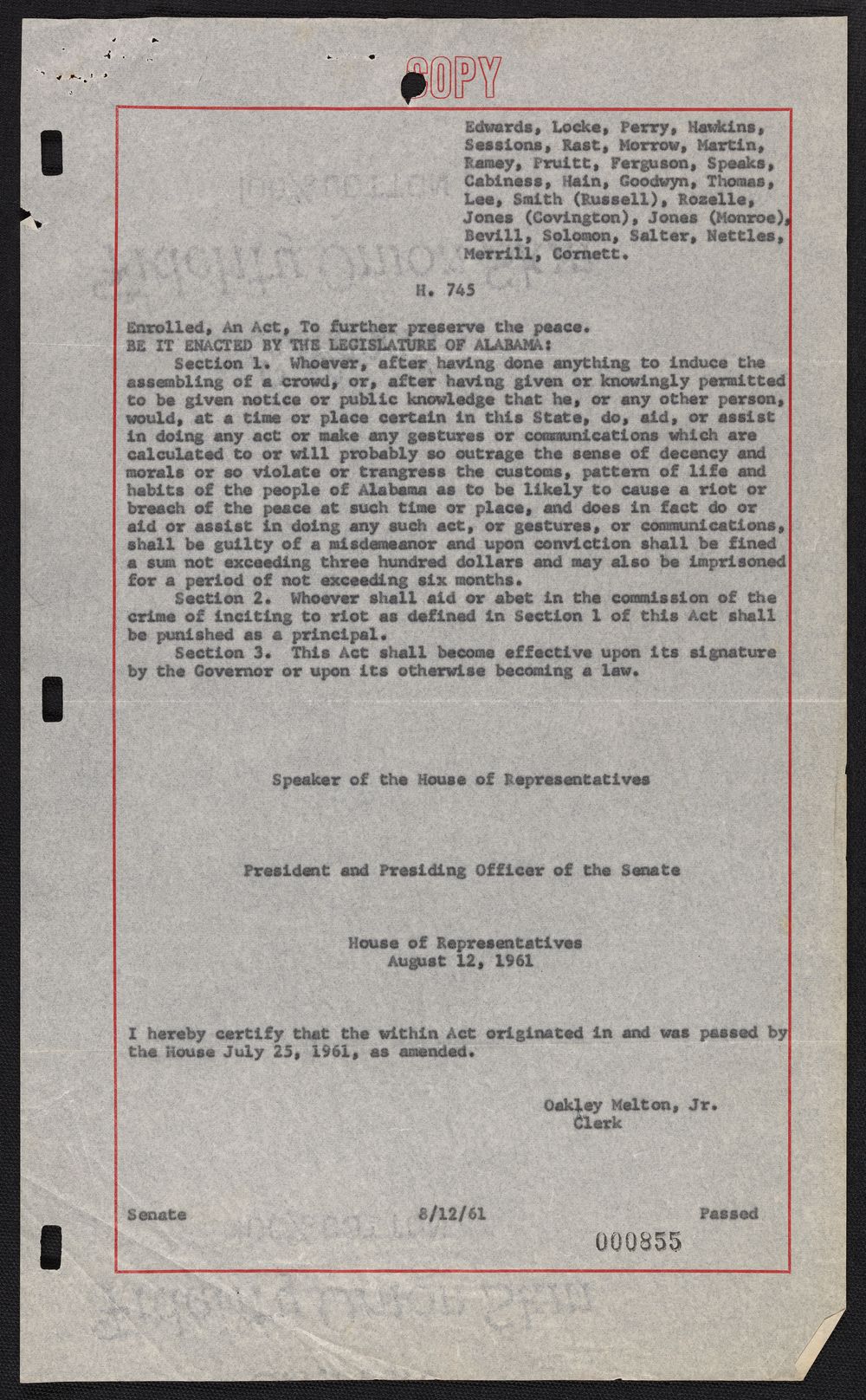

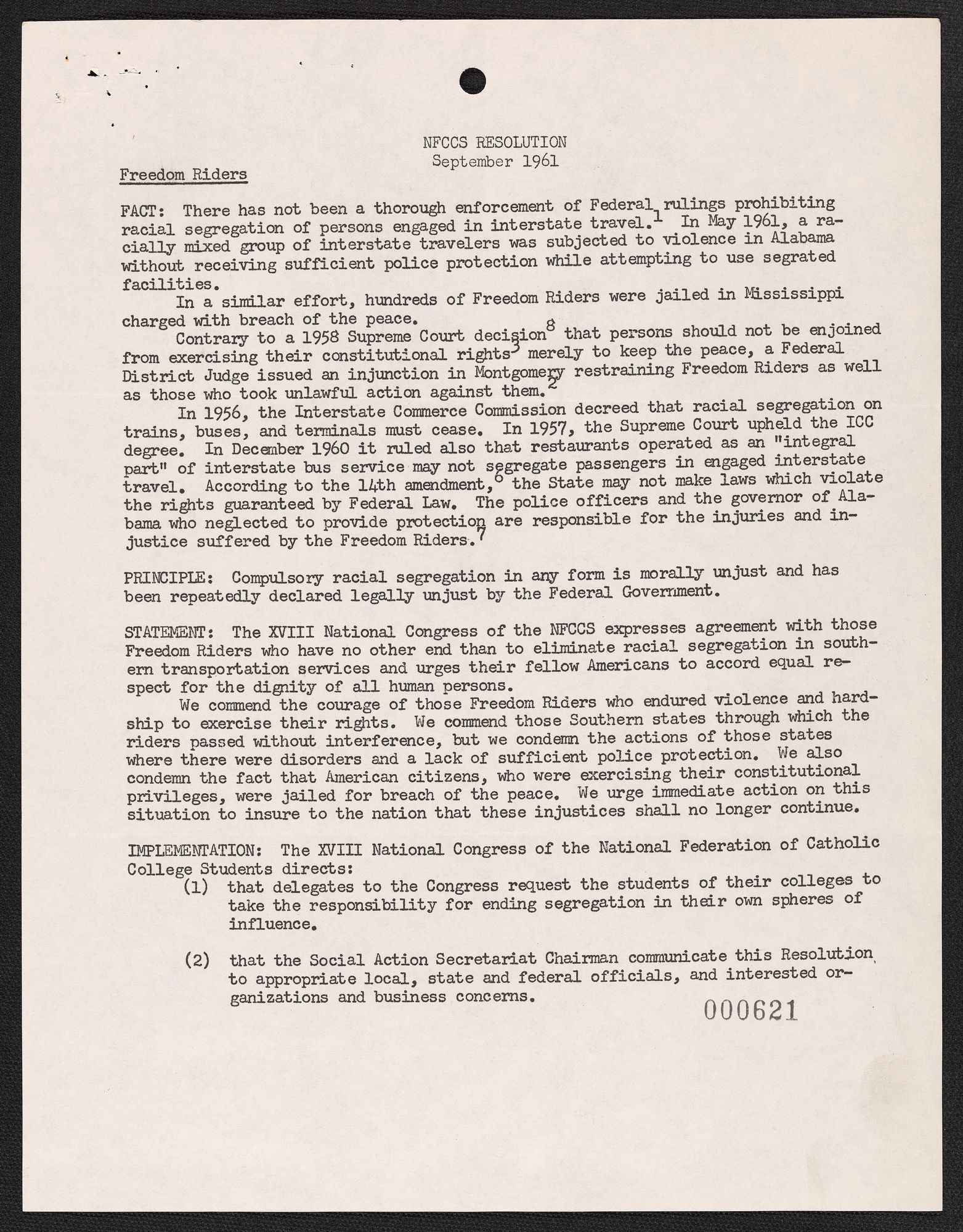

Alabama State Legislature act H. 745, August 12, 1961

The law against making “any gestures which are calculated to or will probably so outrage the sense of decency and morals or so violate or transgress the customs, pattern of life and habits of the people of Alabama as to be likely to cause a riot” targeted the Freedom Riders specifically, and passed in July, while Rides were still taking place.

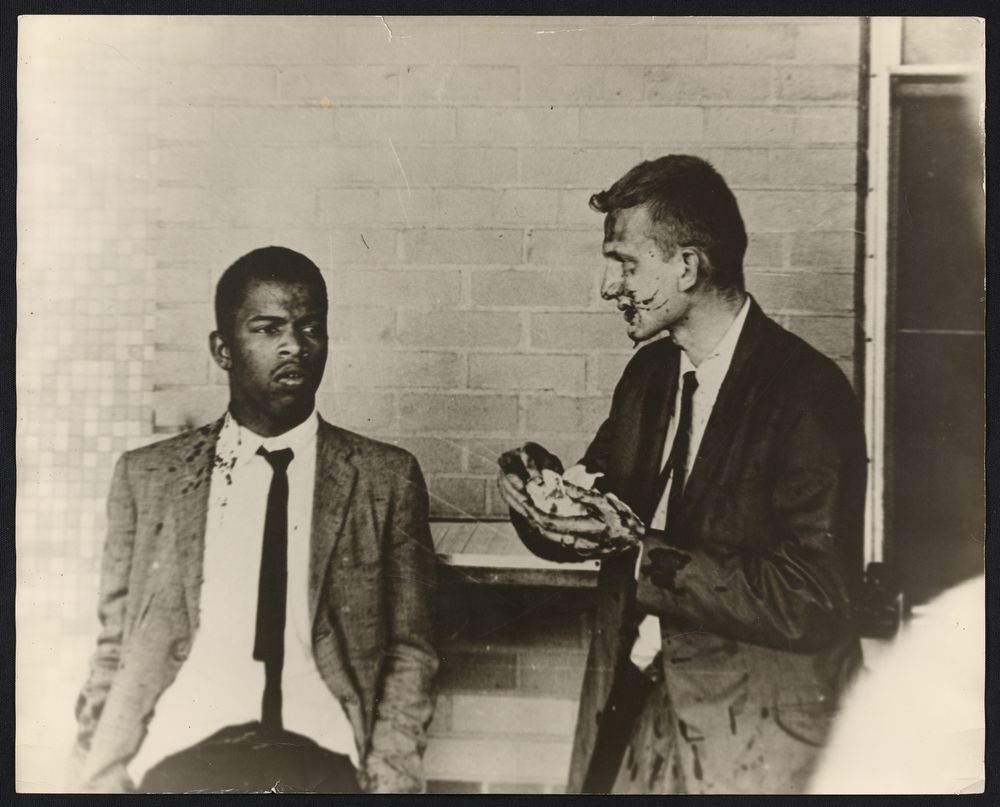

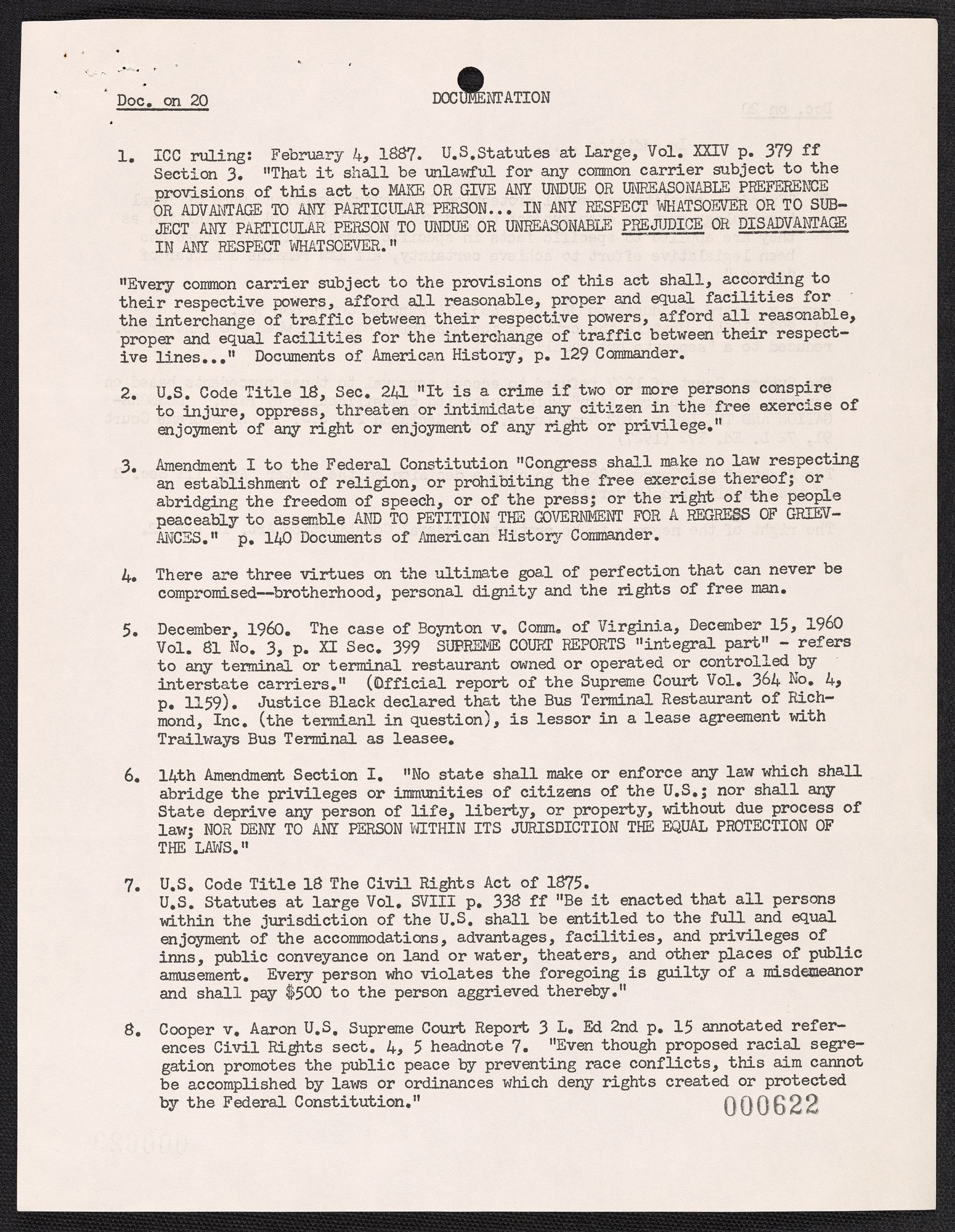

John Lewis and Jim Zwerg after attack in Montgomery, May 20, 1961

Black and White Photograph

Photographer Unknown

Freedom Riders reached Montgomery on the morning of May 20. John Lewis had just begun speaking to the press when violence broke out. Jim Zwerg, a Freedom Rider and exchange student at Fisk University, was beaten by a large group. John Doar watched the violence in Montgomery from the Federal Building opposite the bus terminal, narrating events to Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall over the telephone.

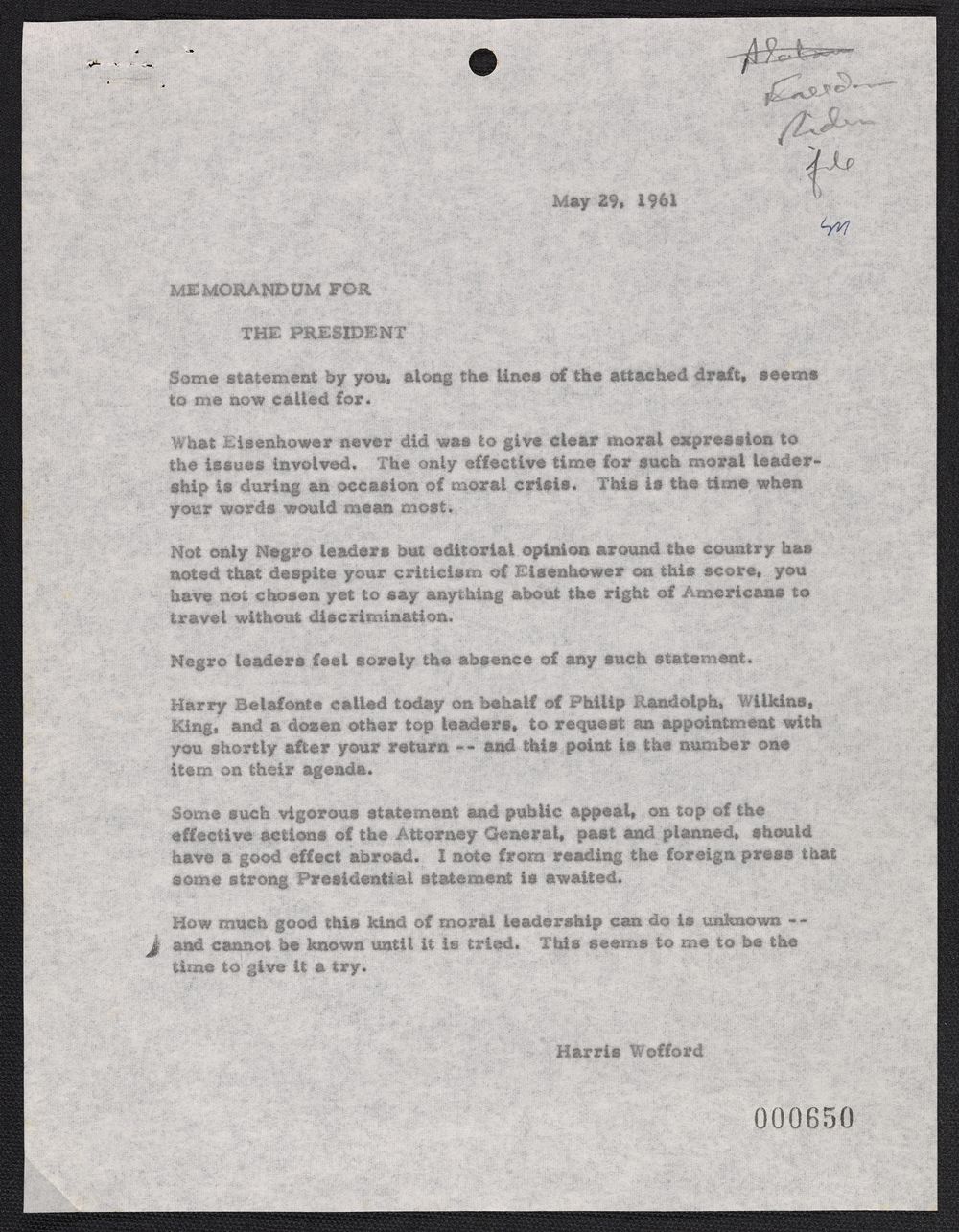

Memorandum for the President, from Harris Wofford, May 29, 1961

On the heels of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961, the Freedom Rides focused attention on domestic injustice. The timing of the Rides was less than welcome to the Kennedy administration, which had been endorsed in 1960 by Alabama’s segregation-supporting governor, John Patterson. Once a campaign aide to Kennedy, Harris Wofford was appointed Special Assistant to the President for Civil Rights and would later participate in the Selma to Montgomery march.

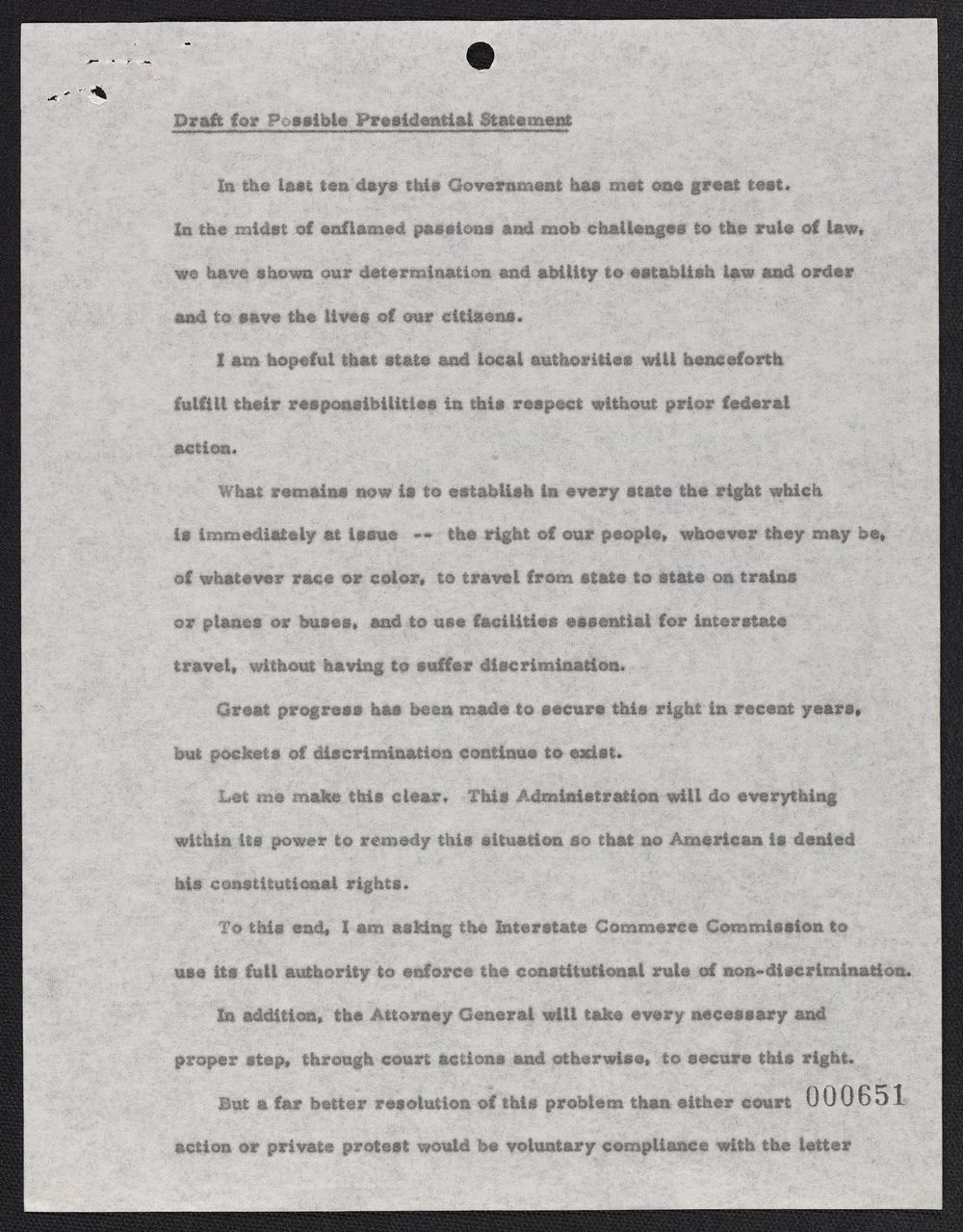

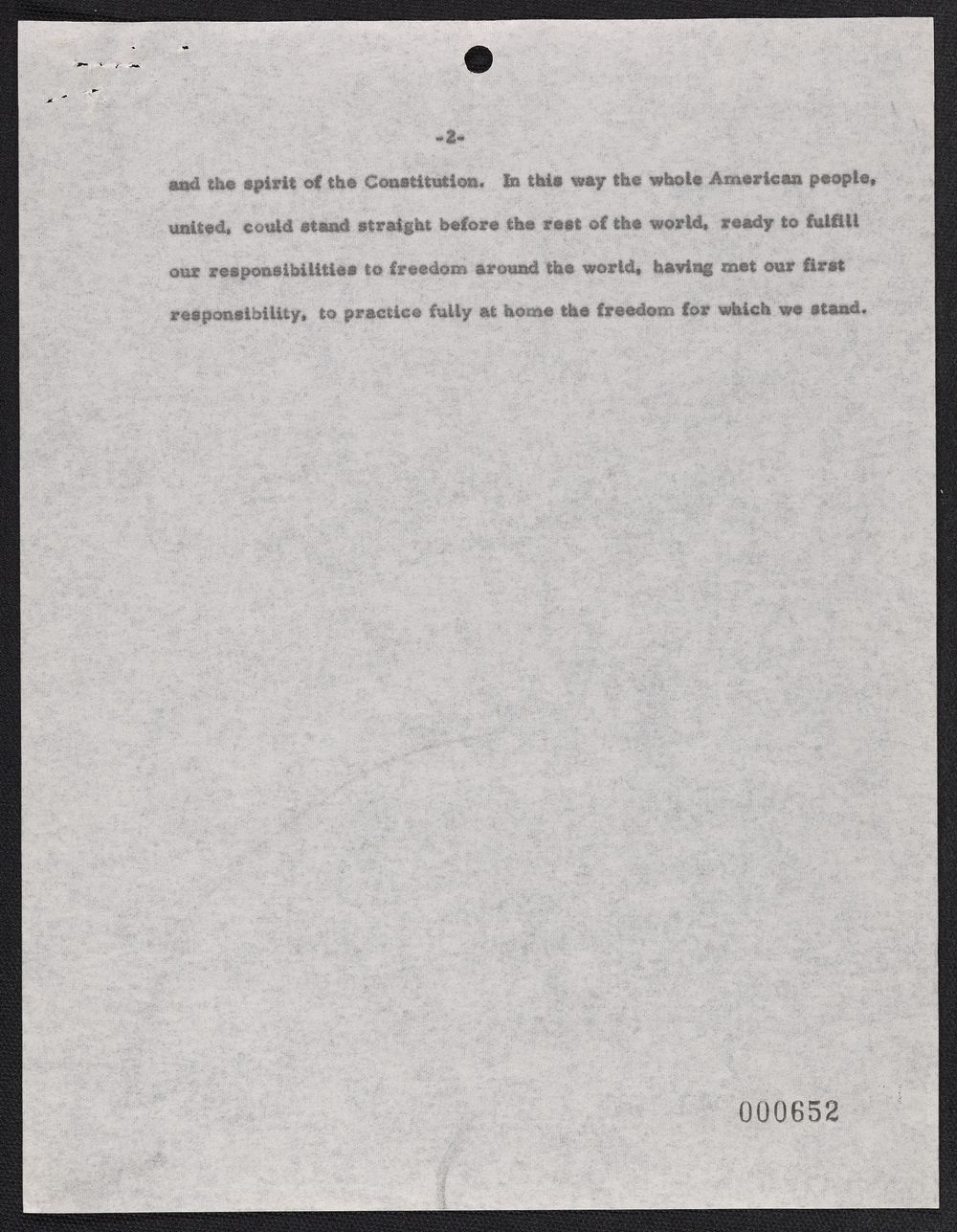

Draft for Possible Presidential Statement, May 29, 1961

The draft statement calls on the ICC “to enforce the constitutional rule of non-discrimination.”

Even as the first arriving group was arrested in Jackson, where they would refuse bail, more groups were following, originating in towns across the South. “Fill the jails” became the Riders’ plan. Close to two hundred Freedom Riders would be imprisoned–many were sent to the penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi–among them John Lewis, James Bevel, and Stokely Carmichael. Many iterations of Freedom Rides would continue all summer.

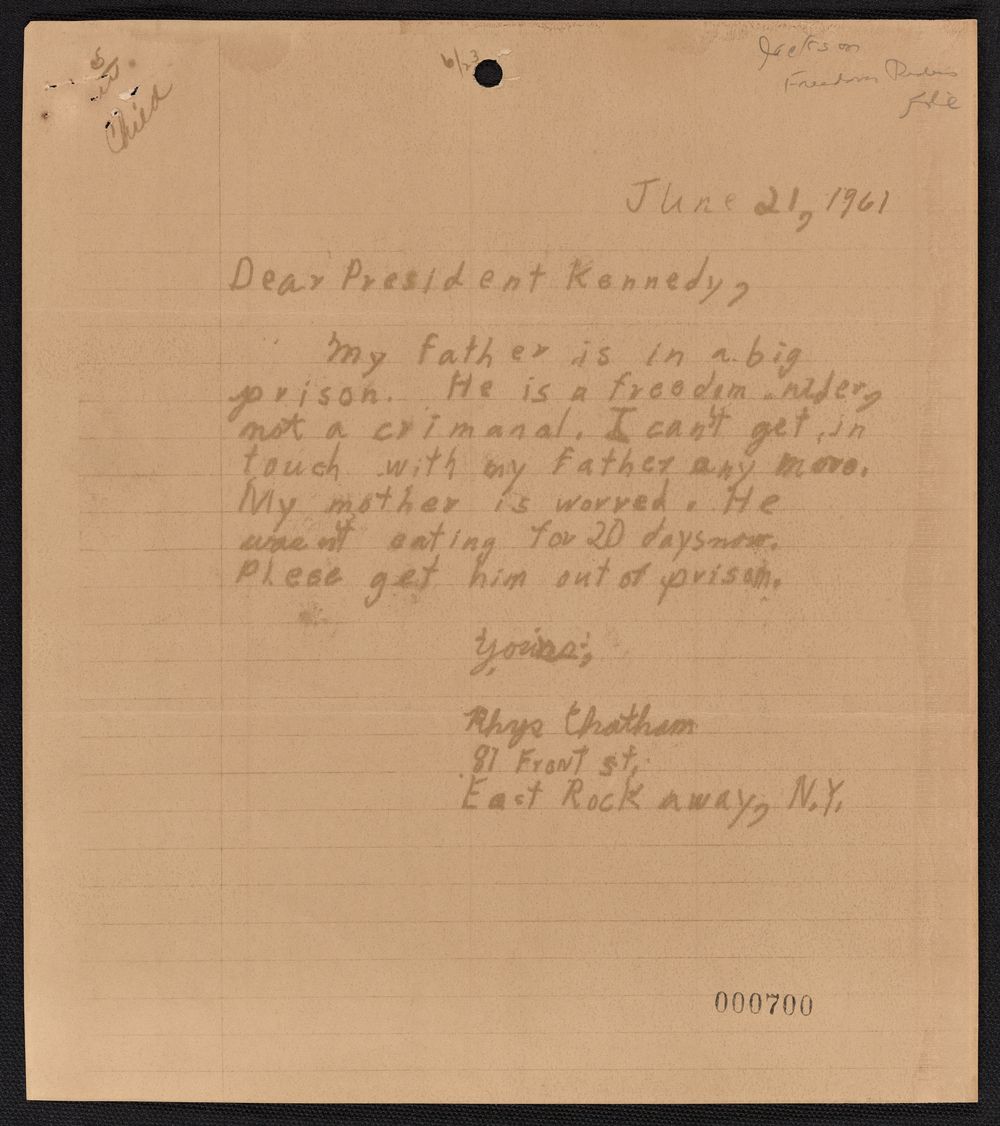

Letter from Rhys Chatham to President John F. Kennedy, 1961

In this letter to President Kennedy, Rhys Chatham pleads for the release of his father, Freedom Rider Price Chatham, from a Jackson, Mississippi penitentiary, where he was on hunger strike with other Freedom Riders.

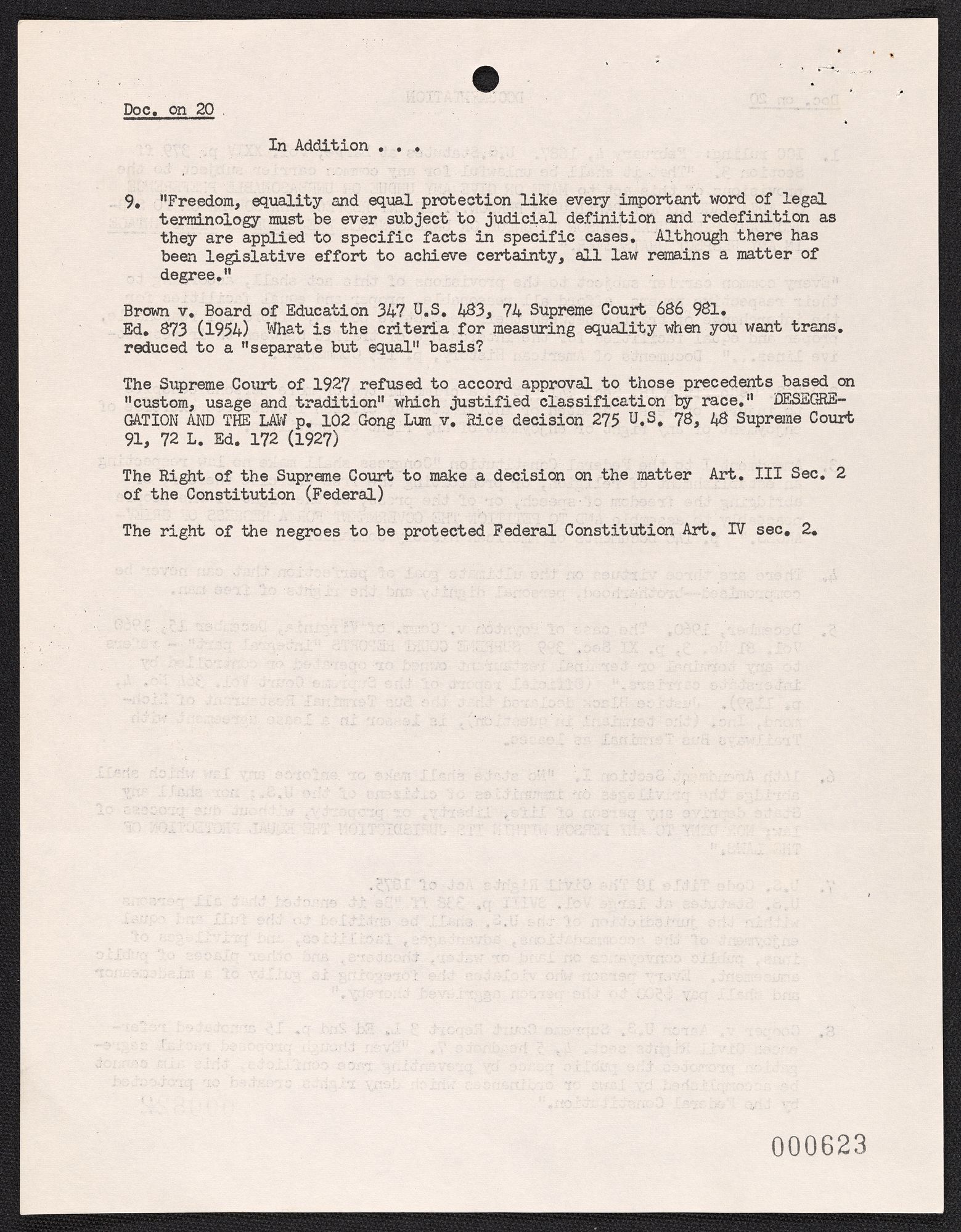

National Federation of Catholic College Students Resolution, 1961

By the end of the summer of Freedom Rides, the National Federation of Catholic College Students reacted with a statement of support for the Riders and a call to its members to “end…segregation in their own spheres of influence.”

Robert F. Kennedy ultimately pressed the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) for a ruling outlawing segregation in interstate bus terminal accommodations, an idea originally put forth by Martin Luther King, Jr. The ICC handed down the order in September, 1961.

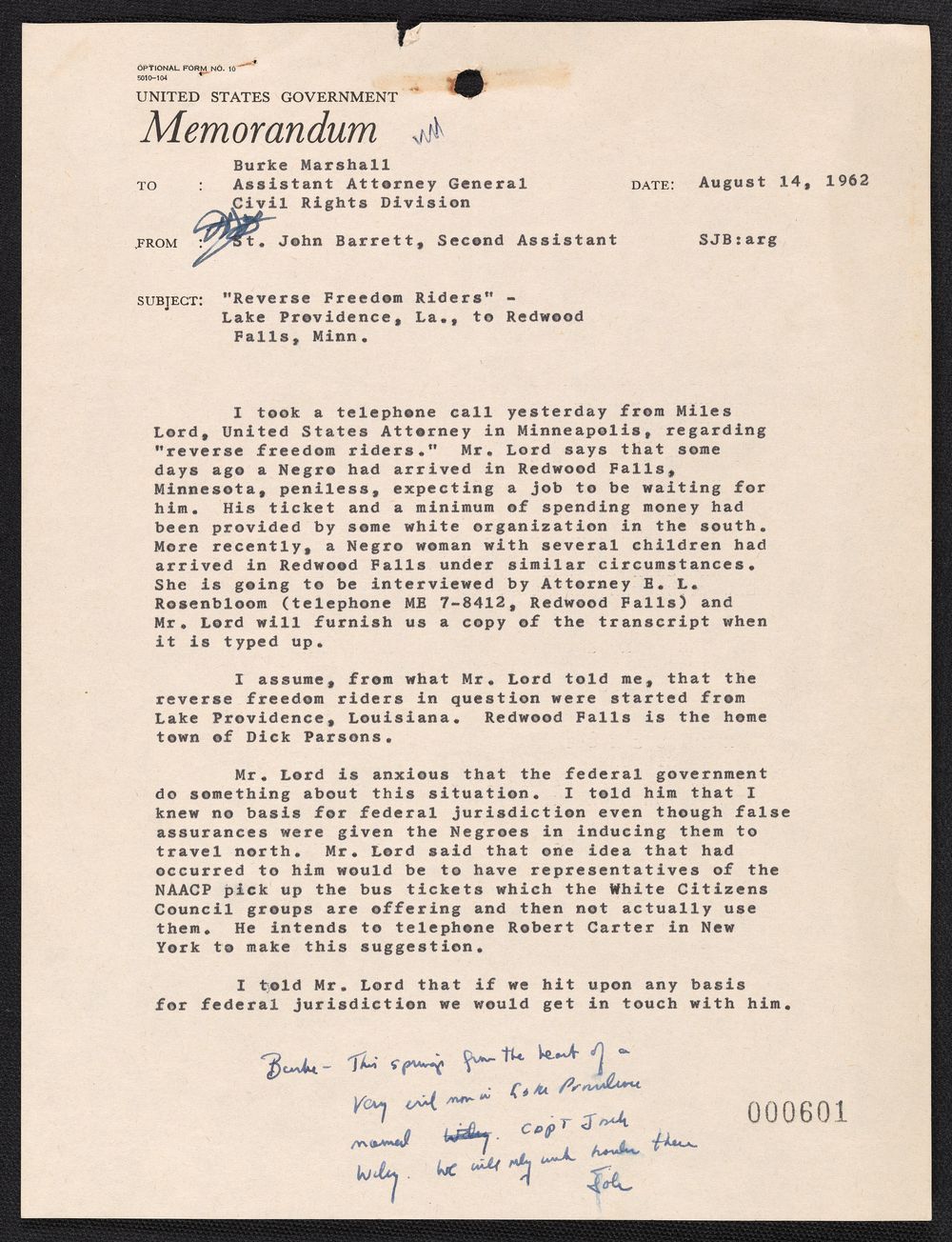

Memorandum from St. John Barrett to Burke Marshall, Assistant Attorney General, 1962 (left)

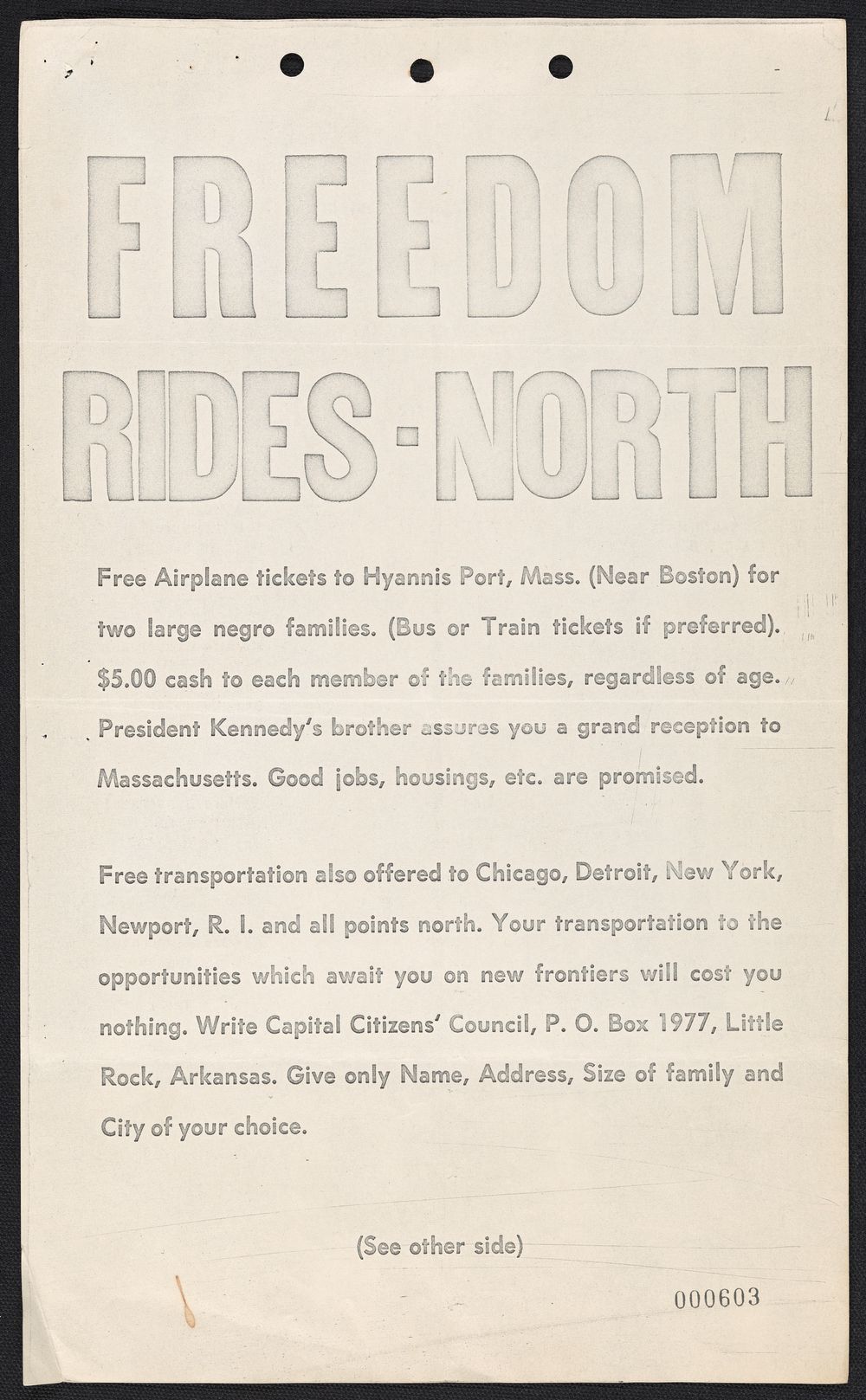

“Freedom Rides–North” flyer, Capital Citizens’ Council, undated (right)

More than a year after the first Freedom Rides, White Citizens’ Councils in the South enacted a cruel parody, offering bus tickets north with false promises of work. In this memo, Department of Justice Civil Rights Division attorney St. John Barrett reports the so-called “Reverse Freedom Rides” to department head Burke Marshall.